The Cycle of Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis

To perform solve on large scale subjects, it’s necessary to have a perspective on progress and the course of history. This is because at the grandest scales, moral questions require context in the form of some direction society is ultimately moving in; some imperative which extends beyond the limited domain of the individual, and which allows you to place yourself relative to the human race as it currently exists, and as it has existed across time and space.

To perform solve on large scale subjects, it’s necessary to have a perspective on progress and the course of history. This is because at the grandest scales, moral questions require context in the form of some direction society is ultimately moving in; some imperative which extends beyond the limited domain of the individual, and which allows you to place yourself relative to the human race as it currently exists, and as it has existed across time and space.

Most people in the world today operate under a de-facto understanding of progress, rather than an explicit one: the “End of History” model, inherited from Hegel. They hold that society’s current configuration is “as good as it gets”, and their posture towards the world reflects this, even if their words do not. They project our society of corporations and representative democracies into the boundless future, and seek to reshape every culture and nation in its image.

In truth, this vision of the world is not so much subscribed to as pleaded for by the 3c majority, who since the 1960s have lived in constant retreat from their own tendency towards solve. They subsist in the delusion of the eternal summer, the breath eternally held, and struggle day in and day out to repress the irrationality of it all. They can’t truly conceive of progress, because in adolescence they constructed their worldview to suit the societal structures which currently exist. To them history is a static, finished thing, in which forward progress is impossible, and the greatest imperative is to feed the fires of the present, sacrificing any qualm-giving or conflictual notions at the altar of this eternity.

In this chapter, I will lay out a model of history grounded in the premises of the Framework. Unlike the model I’ve just described, which largely serves as a coping mechanism to be employed in the tedious humdrum of denial, this model will be centered on a narrative of progress. It will be a model in which things get better for the human race over time, and which implies ethical boundaries and makes ethical demands of the people within it. This, I feel, is the primary value of the Framework as it applies to history; that it gives us a lens through which to view otherwise esoteric and immaterial moral questions.

It’s not well-suited, by contrast, to serious or specific historical inquiry. “Why do we consider the Romans our historical forbearers, even though we find them morally repugnant?” is a good problem for the Framework to break down. Questions like “What prompted the dissolution of the latifundia in Roman Britain in the 5th century?” on the other hand, are much better suited to fine-grained analysis regarding the logistical and material conditions of the situation. The Framework’s model of history serves these questions best as a jumping off point, and as a systematic way of making explicit your own premises and assumptions, which might remain latent and obscure in a more traditional historical analysis.

Any model of history informed by the continuous interchange of Eros and Thanatos will center on the cyclical centralization and decentralization of society. In the former instance, society gathers around a single pole, wherein societal will and legal power are centralized; in the latter instance, society devolves into many separate, more local poles. Within the Framework, the historical eras in which society centralizes are referred to as Antithesis eras; the eras in which society decentralizes are called Thesis eras.

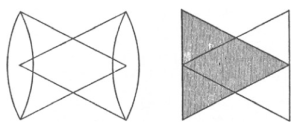

I have taken this model of history primarily from WB Yeats, who laid it out across a bewildering array of charts in his monumental philosophical tract A Vision. As each era rises to its apex, the other diminishes, and vice versa:

I have inverted the terms relative to his use of them. He based his assertion that the Capitalist era was “Primary” on the fact that he was writing from within it, and called Feudalism “Antithetical” as an extension of this. I include a Synthesis phase in my model which clearly demarcates each complete cycle from the previous, which necessitates placing the prior Feudal era in the “Thesis” spot and the Capitalist era, by extension, in the “Antithesis” spot.

As discussed previously, the sublimation levels are ultimately the cyclical re-expression of the same dialectics of need fulfillment at higher and higher levels of complexity. This movement towards greater complexity and lower urgency is the driving force of progress within history, and it’s this movement which constrains the format of society.

That is to say, the alternation of society between centralization and decentralization doesn’t cause moral progress along the Ladder of Sublimation; rather, it is moral progress along the Ladder of Sublimation which drives the alternate centralization and decentralization of society. The answers to the collective action problems embodied in human needs are given, and experience no feedback-effects from the transitory conditions of society. That society constantly embodies the interchange of centralization and decentralization without deviation from this pattern is a function of the construction of human needs, rather than a coincidence. However, the question of why needs are constructed in this way lies beneath the level of philosophical granularity that this BlogBook is intended to investigate, so for now we will simply treat it as a given.

In summary, a premise: There are no emergent properties or knock-on effects resulting from a hypothetical interplay of society with the unfolding process of sublimative progress.

As an aside, the lack of mimetics and feedback loops within this system of societal evolution precludes the subversion of society by “Great Men”. This is a frame of history which reaches its clearest expression in Nietzsche’s “blonde beast”, the charismatic, animalistic figure who overwhelms and hoodwinks an otherwise rational society in the manner of a Napoleon or Hitler.

Generally this notion is looked down upon in academic circles (except insofar as it allows a culture to scapegoat a charismatic dictator for some atrocity which was, invariably, actually deeply rooted in their outlook and way of life). That charismatic leaders are largely irrelevant to the course of history emerges as a truism within the worldview of the Framework, owing to the lack of mimetic effects by which an action might “ripple outward” towards disproportionate consequences. After all, a leader is only a leader insofar as he is able to convince people to follow him; he is sustained only by the action or inaction of the governed. Tyranny, where it arises, is an outgrowth of a historical process, not an accident society wanders into. If any specific leader fails to fulfill the role laid out for them by their followers, they will be replaced.

Likewise, those great men who make the philosophical arguments which constrain or motivate the actions of later people— Jesus, Buddha, Calvin, Gandhi, MLK, etc.— are not in a true sense inventing anything; the latent boundaries of possibility-space, the actions which it would be sensical for a human being to take, are laid by the nature of the interchange of needs and means. Philosophical arguments are discoveries, not inventions, and are more or less bound to be replicated elsewhere in function if not in form insofar as they are useful, except where stagnation is imposed by the material limits of a civilization (e.g. among the Aztecs).

Having dealt with the frontmatter, we can now begin to discuss what the cycle of Thesis and Antithesis actually consists of, and how it may be used to perform solve on subjects which are too broad to dissolve with dispositional analysis alone.

Antithesis eras are the historical eras in which individuals are inculcated en masse with closed dispositions. The institutions which these individuals create cater to the irrationalities and desires which comprise their pathology. The repressed desire of the closed individual is for freedom, power, and the esteem of others. The conscious duty of the closed individual is toward conformity. As a result, Antithesis societies are constructed to reward conformity with freedom, power, and esteem; they exploit the bargain constructed by the closed psyche to create a chain of submission and domination which extends from the most powerful member of society to the weakest. One rises through the chain by conformity to the ideal of the society in question, and one falls by deviating from it. At the base of the chain, unintegrated minorities are oppressed as subject peoples of the dominant civilization; at its top, social power is centralized into a single figure, a single pole around which the world orbits; Caesar, Fuhrer, President, General Secretary.

This entanglement of conformity and rank creates a highly active, prehensile society. Relatively rapid rises and falls and the spirit of conformity create both economic surpluses and a concern for posterity, and the result is an explosion of creative energy. At their peak, we think of Antithesis stages as “civilized”, because the art and monuments by which a people inscribes itself into the historical record are the products of concerted effort. The closed mind hungers for an avenue of achievement, to be given things not because of who he is, but what he does; in youth, he is denied conditional love by his parents, and is thereby precisely crafted to substitute society in their place.

There have been three Antithesis eras in recorded history, one for each layer of sublimation. I will focus on the progression of these eras in the “Western” tradition, because it is the historical tradition with which I’m most familiar; keep in mind that other regions of the world underwent this progression of eras in parallel, stagnating at different stages of development until the advent of globalization with the Industrial Revolution. The three historical Antithesis eras are:

- The Bronze Age (1c, Physically Closed)

- The Hellenic Era and Roman Republic (2c, Emotionally Closed)

- The Capitalist Era (3c, Socially Closed)

I will discuss each of these eras in more specific detail elsewhere in this BlogBook.[1]

The boundaries at which a rising Anthesis era meets a waning Thesis era are marked by revolution. Closed institutions mature in the background of open ones, rising in power as the Thesis era declines from its peak. At the equinox of waning Thesis and waxing Antithesis, the tighter integration of these closed institutions allows them to outmaneuver open institutions, gaining a veneer of self-consciousness in the process; for the first time in centuries, actions are carried out in the name of ideas, rather than of men. Reciprocally, much of the violence of a revolution can be attributed to the exploding forth of the repressed Thanatos impulses of its closed participants. This dynamic can be seen across all the revolutions of history, from the rise of Athens, to the French Revolution, to the “Communist” revolutions of the 20th century.

The excess of an Antithetical era is atrocity. The unity of society around a single pole produces incredible clarity of action, and the mass repression of Thannatical drives leads to the creation of a populace who are unable to reckon with the reality of death, which they secretly long for. Death is therefore dealt wantonly downward along the chain of submission and domination.

This happens because a fully closed society lacks the capacity for self-reflection, and the ethos of conformity-as-virtue develops into a notion of conformity-as-personhood. As the Antithesis era reaches its peak, the chain demands ever greater conformity from the people at its apex; this creates ever greater strain on their subconscious minds, which bear the weight of their repression. They vent this strain through acts of violence against the nonconformists at the base of the chain— through the lens of closed hysteria, unreal death is dealt to unreal persons. Antithetical institutions, keenly aware of this process as it unfolds, are bent to the will of the populace, and the result is massacre and persecution. Salient examples include the massacre of the Gauls by Caesar, the persecution of the early Christians by the Romans, the Holocaust, and the Cultural Revolution in China.

An Antithesis era represents the eternal summer, the breath forever held. The chain of submission and domination extends ever outward, constantly entrapping new peoples. To those wrapped up in it— to those with era-appropriate closed dispositions— such a wave must feel as though it will go on forever, washing across the entire planet. However, each Antithesis era is attached to a particular sublimation level, and as a result the maximum extent of any society is limited in time and scope. Capitalism, for instance, operates on a timescale which refreshes across months and years, and for reasons of language can subsume only those within a single nation-state. Dialectics cannot be sustained across longer spans of time, and cannot subsume people who aren’t willing or able to share the vernacular and culture of the majority. When the wave of an Antithetical civilization reaches its maximum extent, it turns inward, and devours itself. When the wave of an Antithetical mode of being reaches its logical conclusion, as demonstrated by its collapse into atrocity, it is abandoned, and dissolves.

Thesis eras arise from the mass-inculcation of the population with open dispositions, and these open pathologies constrain them in form and structure. Open individuals secretly crave safety and security, and feel a duty to novelty, and so open societies are designed for maximal stability within a limited purview. Hard work and social station are disentangled, giving rise to heritable offices and life-stations which, in their inflexibility and permanence, replicate the unconditional love which open individuals are denied by their parents in childhood. The great chain of submission and domination is shattered into pieces which are local, proximate, and consists of ties between individuals without any greater collective identity.

The dispersal of society into these atomic hierarchical chains creates a structure which is built for permanence. Open societies can persist on the barest ideological soil. Individuals are liberated from submission to society as a concept, and instead pressed into the service of their human superiors[2]. This lack of central authority leaves society sluggish, feeble, and incapable of generating the great works by which a culture imprints itself on history; but this same lack prevents society from interfering as greatly in the operation of its members, and diversity of behavior and attitude (within the active sublimation level) is allowed to bloom fully.

Occurring between Antithesis eras, there have been two Thesis eras in recorded history; however, owing to the collapse of centralized hierarchies, information on these eras is scarcer than on the closed eras. In line with my approach to listing Antithesis eras, I will be focusing on the history of “Western” civilization; other civilizations have certainly entered Thesis eras at various times, but this is the lineage of sublimative progress with which I am most familiar.

- The Bronze Age Collapse/Greek Dark Age/Homeric Greece (2o, Emotionally Open)

- Feudalism (3o, Socially Open)

I will discuss each of these eras at greater length elsewhere.

The boundaries at which a rising Thesis era meets a waning Antithesis era are marked by nonparticipation. The growing Synthesis doctrine which emerges at the end of an Antithesis era teaches individuals to reject the injustice and tragedy which accompany the societal chain of submission and domination. Society collapses, as increasing numbers of individuals “opt out” of the institutions and lifeways which keep society functioning. Social organization retreats to the simpler structures which have been proven durable, such as the family. As social institutions reform around the newfound Synthesis doctrine, the void of authority created by the collapse of centralizing institutions leaves parents with no overt need to condition their children on the sublimation level which constitutes an emerging field of conflict; at the appropriate age, these children are left to their own devices, and are therefore inculcated open.

The excess of a Thesis era is stagnation. The subconscious craving of the open mind for security entrenches patterns of behavior as dictates without justification or review, obstructing the conduct of life. Thetical societies can survive on the barest of rocks, kingdoms held together among vassals who neither know of nor care for one another. But the arbitrariness of their social constructions, while making them durable to critique, also makes them oppressive and limits growth or improvement. When crisis strikes, these societies are incapable of reacting, and are prone to re-entrenchment in failing lifeways. Examples of Thetical stagnation include the conflicts between the glory-hungry princes of the Iliad, the strictures of feudal sumptuary law in the middle ages, and the failure of feudal institutions to recover from the Black Death.

The geographical and temporal extent of a Thetical society is proportional to the difficulty of the terrain over which it is splayed. The more cumbersome travel and communication are between the components of a Thetical society, the less vulnerable it will be to conquest and absorption into a domineering empire. Framed another way, this may be presented as something of a truism; the more difficult it is to centralize a body of terrain under one government, the more likely individuals will be to invest in local authorities.

Having established the characteristics of Thesis and Antithesis eras, it’s important we understand that each era creates itself in reaction to the former, and that this reaction is an engine of progress. The excesses of each era naturally give rise to crises, and these crises prompt introspection which shakes the balance of power. The Second World War and the excesses of the holocaust gave rise to the hippies and the anti-authoritarian turn of American culture in the 1960s. The Black Death empowered the peasantry, who took advantage of the drop in population to carve out a new mode of yeomanry which more greatly entangled hard work and economic success (and gradually gave rise to the burghers as a dominant societal force). A premise, then, of the Cycles of Thesis and Antithesis, is that they are a model of history in which societal change is driven by people’s individual responses to the essence of their society in times of crisis, rather than by circumstance, philosophical doctrine, or logistical constraints— all of which are down-stream of this dialectic. That the pattern of Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis is followed so closely is a reflection of the fact that, at these massive scales, each step is logically contingent on the previous; this is ultimately a product of the interchange of Eros and Thanatos.

However, the interchange of Eros and Thanatos is the furthest “downward” extent of this book, so we won’t be interrogating it any farther here. Keep in mind that the Framework Blogbook seeks to give you a Framework to use, not a set of facts to believe. You can and should be interrogating this historical framework against your own intuitive understanding of history. Does it align with what you believe regarding the facts of the matter? If not, can it be modified to align with your view of the facts, without destroying its fundamental basis?

Having laid out the cycle of Thesis and Antithesis, we must explore Synthesis, which does not constitute an era within the circulation of the fundamental forces, but instead emerges simultaneously from their interchange.

The Cycle of Thesis and Antithesis is repetitive, but it is not stagnant, because each Antithesis culminates in a Synthesis, a durable, portable, sensical doctrine which summarizes what was learned in the prior turning of the wheel.

These doctrines are transmitted throughout the next Thesis era, and achieve maximum saturation in the next Antithesis era; they are internalized to the point that they become subconscious. They are generally religious in nature. For example, doctrines of Synthesis from the collapse of the 2nd Antithesis era include Christianity, Islam, Chinese Buddhism, and Rabbinic Judaism[3].

It should be noted that the difference between a Synthesis ideology and ideologies of Thesis and Antithesis is that a Synthesis is rational (self-consistent), and can be transmitted to adults. Thesis and Antithesis ideologies are irrational (not self-consistent) and therefore can only be transmitted to children in their upbringing, such that they are able to calcify below the reach of incidental solve. This self-consistency is what is meant by “sensical”, and this transmissibility is what is meant by “portable”.

What is meant by “durable” is that institutions derived from N syntheses persist in the organization of society permanently, even as the superstructure built on top of them changes.

The family is a salient example, emerging from the darkness of prehistory, but still mediated without destruction by each successive format of societal organization. The family represents a boundary of rationality, which can be reconfigured, but not erased, through successive eras of progress. A Roman father might be incredibly strict with his children, to inculcate them 2c; a medieval father, raised in a family structure modified by the synthesis doctrine of Christianity, will not be so strict with is child, but will put them to work with little oversight in their adolescence, as there are no achievements which might realistically alter their lot in life, such that what they do with themselves doesn’t much matter. Moral historical inquiry bears this notion out; inevitably, projects aimed at destroying the family are the result of the nihilism which accompanies loss of faith by individuals living through the alternation of eras, and are not built into the structure of ascendant eras. That is to say, they are an attempt by adherents of a pathology to extend the societal boundaries of that pathology past their natural limits, heaping useful furniture into a dying bonfire.

And here’s a potential example of a future, 3n zone of durable rationality: medieval conceptions of God as the King of Kings to whom all men were accountable may be a manifestation and reminder of the zone of expanded liberty the abandonment of Roman slavery endowed upon the Western ethos. This conception of God as a higher authority than man, fixed permanently atop the chains of submission and domination, proved durable throughout feudalism, and asserted itself in the revolutions which created modern democracy despite hysterical-nihilistic attempts to stamp it out.

I’ll conclude with a final note, something to satisfy those of you who have spent the last few pages asking yourself why any of this is worth thinking about in the first place.

In each era of history, interpersonal dialectics calcify at the age at which the inculcation of pathology ceases. In our modern era, “high school never ends” for 3c Boomers, because the pathologies which animate them are set-in by the end of adolescence, and moral development on top of that is too aimless to override or meaningfully compete with it. And so all Boomer social events are prom, all Boomer couples are sweethearts, and all the masculine urges of the Boomer mid-life crisis revolve around adolescent fixations— guitars, cars, women.

Progress is important, and must be sought after, because the limitations of each era of civilization limit individuals as well, left laboring forever in the lust and fear of the unhappiest periods of their youth. Progress is our liberation by degrees from this struggle, and progress is a project of the entire human race.

- Liberal Democracy was not a proper or complete instantiation of an Antithetical social order, because it was counterbalanced by a significant interior-periphery of 3o women, creating an inefficient simulacrum of a 3N society. I’ll visit this in more detail in a later chapter. ↵

- See the tax rebellions of England which came about after Feudalism had reached its peak— the king could insist that his lords supply him with individual soldiers, but he couldn’t levy taxes in general. ↵

- Original (Lesser Wheel) Buddhism was not a Synthesis Doctrine, it was a closed philosophy, alongside the philosophies of Axial age thinkers like Plato and Lao Tzu. ↵

The tendency of thought which dissolves whole objects into smaller, more comprehensible pieces. Aligned to Thanatos. Opposite of unio. From the pidgin Latin alchemical term. Pronounced "soul-vay" or "soul-way".

A tool of solve which explains human behavior and human history in terms of 9 dispositions.

A tendency towards unity; the life drive; in human behavior, the drive towards security, safety, submission, prudence

A tendency towards separation; the death drive; in human behavior, the drive towards danger, challenge, achievement, risk-taking, independence

The thesis era which preceded capitalism. Society was organized along a diffuse basis, in which merit and hard work were disentangled in favor of stability. The feudal era collapsed as a result of the Black Death in Europe, which gave the ascendant burghers and yeoman sufficient bargaining power to begin the long defeat of the nobility.

The current era of history. An antithetical era, dominated by Eros, in which society is highly centralized. Capitalism within the context of the Framework is more properly "corporatism", as the corporation of individuals with a shared basis of interest is the fundamental unit of capitalism, and the organization of society into a ladder of submission and domination employs the corporation as its basis.

Human behavior consists of interacting with collective action problems at discrete levels of increasing complexity and decreasing urgency. These levels of increasing complexity and decreasing urgency- of abstraction- are referred to as sublimation levels. There are three sublimation levels which society has progressed through in the historical record, and two of these levels are still active fields of conflict which human beings develop pathologies on in the modern world.

The intervals of abstraction at which humanity's collective action problems cluster. The process of history is the process of ascending this ladder through civilizational development. The process of childhood development is the process of internalizing the solutions to these collective action problems.

Dispositions pathologically aligned with Eros. Given, as a result, to consistency and avoiding danger. Tend to be quiet, interrupt people rarely, etc. Bear a pathological preference for low-risk, low-reward activities.

That which your lower mind craves, because the conditions of your pathological bargain have caused it to be scarce.

The means by which your pathology instructs you to pursue your desire while avoiding your fear.

The organizing principle of the closed societies, that all human beings within a society are arrayed in intersecting vertical hierarchies of submission and domination which stretch from the lowest, most base individuals to the highest, most exalted ones. Movement along this chain is possible according to one's conformity to that society's ideals.