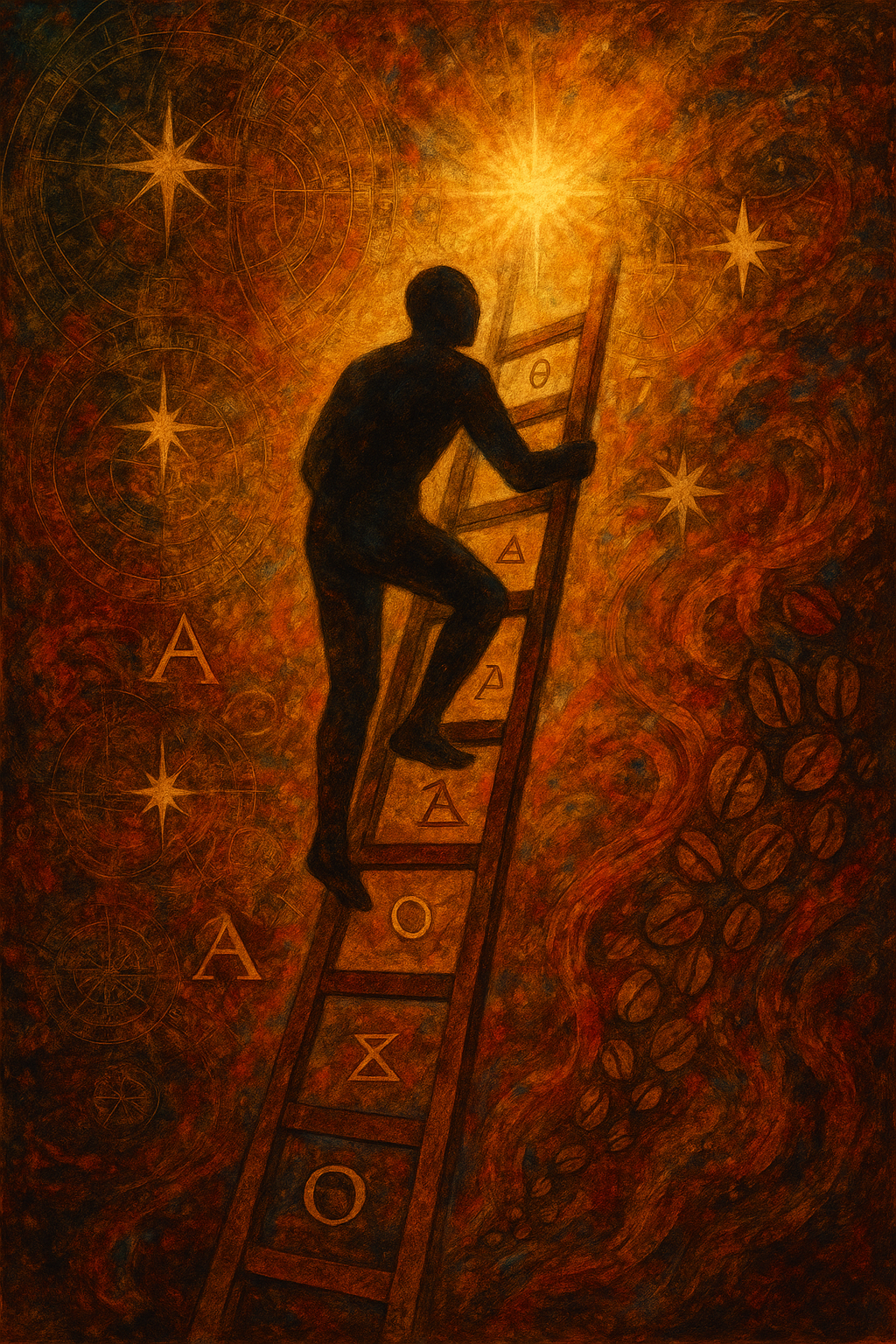

The Ladder of Sublimation

Solve is the process of finding yourself, of locating yourself against the backdrop of human diversity. Comparison and contrast with other people is the most powerful tool we have to contextualize ourselves; at the broadest scale, this process of contextualizing oneself must involve the study of history.

Solve is the process of finding yourself, of locating yourself against the backdrop of human diversity. Comparison and contrast with other people is the most powerful tool we have to contextualize ourselves; at the broadest scale, this process of contextualizing oneself must involve the study of history.

The Ladder of Sublimation is the element of the Framework which you can use to place yourself and the people around you within a broader historical perspective, and it’s the second of the three pillars which form the backbone of solve analysis. This chapter lays out the Ladder of Sublimation, which at its heart describes a cycle of Eros and Thanatos in which human civilizations encounter, and solve, a series of collective-action problems at discrete levels of increasing intensity and decreasing urgency. The result of our resolving these collective action problems is moral progress.

Progress is the central theme of the Ladder of Sublimation, and it’s an essential part of the moral argument this book seeks to make.

There’s a good chance, if you’re of a more literate bent, that you felt some part of yourself reflexively cringe reading this. The idea that human civilization progresses along a set path in which some cultures are superior to others— whether those who came before them, or more problematically, those who failed to advance— has been thoroughly dismissed, both in academic circles, and in the educated newspaper-reading echelons downstream of them.

In place of narratives of progress we’ve adopted a great deal of relativism, which generally comes in two flavors. The first of these is the neoliberal Francis Fukuyama-esque “end of history” narrative, which holds that we live in an eternal summer, an ultimate system of capitalist nationhood which, being the optimal configuration of human affairs, will persist for all time (This is really just a rehabilitation of Hegel’s political views, stripping out their more nakedly fascistic and religious characters). The second flavor is postmodern; leftist skepticism which holds every society to be more or less equally effective at addressing human needs, which are the product of memetic viruses infecting the tabula rasa of the human spirit. They diagnose a sickness within our system which has arisen mimetically and can only be defeated mimetically, by enacting a transcendent revolution which will re-mold human nature into a form better suited to our capacities.

Both of these frames, by virtue of their appeal to “complexity”, can be very persuasive. But they are horribly unsuited to our goals here— your goal in reading this blogbook, and my goal in writing it. Our purpose in the study of history is to perform solve, that is, to take the undifferentiated mass of our psyches and dissolve them into smaller, more comprehensible pieces. We are asking of history what we should change about ourselves. A relativist framework of history— in which every society which has ever existed is equal and should be approached without judgment; in which conditions of the present moment persist forever and can only be altered by the transfiguration of what it means to be human— is useless for performing solve, because such a framework contains no bottom. History without a trajectory is history without a moral lesson, and a moral lesson is precisely what we need to carry out the transcendental process outlined in the Framework. So, throughout this chapter, we will use the foundational concepts of Eros and Thanatos, along with an additional premise regarding the character of human needs, to construct a view of history which will be the foundation of everything else to come.

The Framework is a system for understanding human behavior. The first premise of the Framework is that every action has a polarity in terms of Eros and Thanatos; the second premise is that human beings act solely to fulfill their needs. A need, put simply, is something that someone wants badly enough to sacrifice something else for it.

Needs are a fairly self-explanatory concept; “if you do something, it’s to get something you want,” more or less, and we won’t need to get much more technical about it than that. However, we do need to establish something important about needs right from the start: needs are not mimetic.

Mimesis is a popular theory of how needs arise. Essentially, it holds that most (or all) desires are like mental viruses; you want things, the theory goes, because you’re told to want them. For example, you see an ad which tells you that iPhones are valuable, so you want an iPhone.

I don’t really believe in mimesis; within the Framework, needs are innate. That means, narrowly, that your needs exist somewhere within you, and cannot be changed. What do change, then— what the proponents of mimesis identify as a change in “what you want”— are the methods you perceive to fulfill your needs. I.e., you see an ad that says that iPhones are valuable; you have an innate desire to be admired, and people who own valuable things are admired by others, so you want to get an iPhone.

With that note out of the way, we return to needs. Another important thing to keep in mind is that almost all of our needs— and fully all of the needs that the Framework deals with— are fulfilled by interacting with other people. From the least abstract needs like “hunger”, to the most abstract like “community”, pretty much every category of human need is fulfilled by interacting either directly with another person, or with an object or institution other people have created. Human beings are possibly an Erotic species, or possibly live in an Erotic era of the universe; our goals always converge, and, when solving problems, we cooperate by default.

In summary, keep these three things in mind about needs: The drive to fulfill them dictates human behavior, they’re innate (not mimetic), and they’re always fulfilled by interacting with other people.

In understanding needs, we divide them up (solve, remember) in terms of how complex of a problem it is to fulfill them— generally, this can be measured in terms of how long it takes to resolve the problem, and how long it takes to implement that solution once it has been found. (We’ll refer to this as the complexity of the need, rather than of the “need-solution pair” or some other term, to avoid weighing ourselves down with more terminology.)

When we do this, we discover something fascinating. This insight— the third premise, if you prefer to remain skeptical— is the most important thing the Framework has to say about needs; it might very well be the most important thing the Framework has to say about anything.

Needs are not distributed evenly in terms of their complexity; they cluster into discrete levels of complexity. Each of these levels of complexity plays out on a different time scale— specifically hours-days, weeks-months, and months-years.

The Framework refers to these clusters of need-complexity as sublimation levels.

Sublimation is a term taken from Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietszche believed that moral values— beliefs about how people should behave— could outlive the material conditions that gave rise to them. In such cases, moral values could evolve to suit the new conditions in which society found itself. For example, Nietzsche held that Jewish conceptions of ritual purity which evolved to suit a desert tribe (circumcision, not eating pork, etc) were sublimated through the evolution of Judaism into Christianity, a general ethos of cleanliness and order which was ground into European culture.

I disagree with this conception of sublimation, because it is, at its heart, mimetic, and endows moral values with a lot of independence, as though they were living creatures. However, I believe that the central operation of Nietzschean sublimation, in which a moral value is re-expressed at a higher level of abstraction, is a brilliant insight.

Within the Framework, sublimation is the process by which a need re-asserts itself at a higher level of complexity, where fulfilling it forms a more complex problem with a more complex solution. This is best illustrated through an example: lust, which plays out across hours to days, becomes love, which plays out across weeks and months, at the 2nd level of sublimation; at the 3rd level of sublimation, love becomes the desire for a life partner, an impulse which we have yet to condense into a single word but which plays out over the course of months to years.

As needs are expressed at higher sublimation levels, they grow more complex, but less intense. That is to say, the process of fulfilling them is more complicated, but the urge to fulfill them grows weaker and is easier to ignore. To capture this phenomenon, the Framework gives the three sublimation levels which are currently active fields of conflict (more on that later) these names:

1st level: Physical (hours-days)

2nd level: Emotional (weeks-months)

3rd level: Social (months-years)

Please keep in mind that, like all of the terminology in the Framework, these names are constructed to be evocative, and should not be taken literally. They refer to the progress of needs through increasing levels of abstraction, from the most basic physical problems to the more abstract societal ones. If you absolutely must reduce these levels down to some equivalent signifier, use their timescales before any other characteristic.

This conception of needs probably brings to mind Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which is a very similar construction. However, you should remember that Maslow’s Hierarchy divides needs in terms of their character, that is to say, it conceives of them as different things which result from different processes of self. The Ladder of Sublimation asserts instead that each level of needs is a re-expression of the same thing, just at a higher level of abstraction.

It should also be kept in mind that, similar to Eros and Thanatos, sublimation levels are a core premise of the Framework. As such, while it represents a phenomenon which I believe actually exists, I won’t be going to great lengths to convince you that it exists. It can, if you are so inclined, be taken provisionally; it is something you can accept for the purposes of understanding this book— you should decide later on, through your own solve observation, whether it’s something you actually agree with.

Why do needs cluster in this way? The Framework as it currently stands doesn’t have any great answers to this question. However, I don’t particularly feel that it needs to.

The most robust manner in which the division of needs into Sublimation Levels expresses itself is in the nine dispositions; the fact is that human beings operate in their decision-making as though each time-scale of need complexity forms a single, entangled whole. Individuals are conditioned (or inculcated) with dispositions on each sublimation level— they ascend the Ladder of Sublimation. In so doing, they develop biases toward Eros, Thanatos, or neither on that level of sublimation. A bias towards Eros or Thanatos is what a pathology consists of.

Whether the levels themselves are the products of this conditioning, or arise naturally from the distribution of innate needs along the scale of complexity, is certainly a fascinating question, but not one of great import to the present, wholly functional incarnation of the Framework Process.

Tucking sublimation levels into our back pocket, we should return to the topic of history. Just as human behavior is dictated by the imperative to fulfill our needs, so too is human history the process by which we learn to fulfill our needs collectively. We fulfill our needs first and foremost through other people; in the process, we form societies. Each society arises in history to meet the imperatives of solving the collective action problem presented by the specific sublimation level which constitutes an “active field of conflict”. Defined narrowly, the active field of conflict is the most abstract sublimation level for which there is not an extant solution.

Eras of history, containing the rise and fall of multiple societies, can therefore be organized chronologically according to the sublimation level which served as their active field of conflict. The process of solving each sublimation level consists of a cycle of Eros and Thanatos, which goes through three stages. I’ll lay these stages out here in brief, though we will deal with them more completely later on.

First, during the Thesis stage, a civilization adopts a solution to the active field of conflict which is oriented towards Thanatos. Individuals during this stage are inculcated with a Thannatic pathology at the active field of conflict. Society takes a diffuse form, as centers of power collapse and social organization devolves to a more local level. At this local level, institutions develop into a patchwork matrix of stability, designed to uphold and withstand routine violence and disruption. In time, this matrix grows too thick, and society stagnates.

In response to the crises imposed by this stagnation, civilization enters the Antithesis stage. Dominated by Eros rather than Thanatos, society centralizes around a central pole. Individuals are inculcated with an Erotic pathology at the active field of conflict. Institutions subsume broad geographic eras; art and culture flourish. However, this centralization makes society highly reactive, fungible, and prone to hysteria, which spills over into atrocity. Atrocity begins to shake society apart.

As Antithetical society collapses, the lessons of both the Thesis and Antithesis stages are related to the active field of conflict by the people living in it. They develop a Synthesis. Unlike the Thesis and Antithesis, which manifest as pathologies, this Synthesis manifests as a moral ideology, an understanding of how a person should approach the active field of conflict which transcends Eros and Thanatos. This ethos is “portable”, unlike a pathology, because it can be adopted in adulthood, rather than just inculcated in childhood. The Synthesis does not, however, represent its own era of history; the cycle of Eros and Thanatos grinds on ceaselessly, and it is always among the ashes of an Antithetical Era, and the rise of a Thesis era, that a Synthesis ideology proliferates.

So, this is the basic pattern of the cycle of human history as told by the Framework. Civilizations rise in response to the emergence of a new, more complicated active field of conflict; they develop two sets of solutions to the problems of this active field of conflict— first, a Thanatic one, second, an Erotic one. They inculcate their children with these value sets as pathologies, and as a result develop complexes of institutions which match them. In time, the pathological nature of these institutions leads to catastrophe— importantly, catastrophe which forms as a result of the logic of their society being carried out to its logical conclusion. As a result, society collapses, and, after the second such collapse, a non-pathological Synthesis regarding the active field of conflict is formed, and a new active field of conflict is addressed in Thesis as this Synthesis is disseminated.

This cycle has repeated three times in our historical memory. Here is how this historical model played out in the “West” (which we’re confining ourselves to because it furnishes us with the most accessible historical examples of the complete arc):

- Physical

- Thesis era: Chalcolithhic, Early Bronze Age

- Antithesis era: Middle-Late Bronze Age

- Synthesis: Unclear, but visible in prohibitions against human sacrifice

- Emotional

- Thesis era: Homeric Greece, the Greek Dark Age into the Axial age

- Antithesis era: Hellenic Greece, the Roman Republic and early Empire

- Synthesis: Christianity

- Social

- Thesis era: Feudalism

- Antithesis era: Capitalism

- Synthesis: In the making; prefigured loosely by Marxist Communism

This should serve as a rough outline of the course of history for the meanwhile, though the past is a foreign country and predicting the future is a fool’s errand. This cycle will be discussed at greater length further on— though admittedly with too much theory and too little historical detail. At any rate, this short chart is good enough for our purposes, and should be sufficient to give you context for our further discussions.

With that, we’ve completed our section on the Ladder of Sublimation. We’ve spanned a great deal of territory in a very short time; don’t worry if you don’t understand most of this right away. This is a pillar of the Framework, and we will revisit these themes and their ramifications many times throughout the following chapters; with use, and familiarity, should come understanding.

For the meantime, we’re onto the next chapter, and the third and final pillar of the solve process: Dominant and Repressed modes.

The intervals of abstraction at which humanity's collective action problems cluster. The process of history is the process of ascending this ladder through civilizational development. The process of childhood development is the process of internalizing the solutions to these collective action problems.

A tool of solve which explains human behavior and human history in terms of 9 dispositions.

A tendency towards unity; the life drive; in human behavior, the drive towards security, safety, submission, prudence

A tendency towards separation; the death drive; in human behavior, the drive towards danger, challenge, achievement, risk-taking, independence

Something that someone wants badly enough to sacrifice something else to get it. Needs are inherent to the human character, and cannot be changed in their content, only in the methods one perceives to acquire them. They are not mimetic.

Human behavior consists of interacting with collective action problems at discrete levels of increasing complexity and decreasing urgency. These levels of increasing complexity and decreasing urgency- of abstraction- are referred to as sublimation levels. There are three sublimation levels which society has progressed through in the historical record, and two of these levels are still active fields of conflict which human beings develop pathologies on in the modern world.

The 1st level of sublimation, at which processes of need fulfillment subsume only yourself and one or two other people and play out on a scale of hours to days. The term "physical" is meant to be evocative and should not be taken literally.

The 2nd level of sublimation, at which processes of need fulfillment subsume yourself and the people close to you and play out on a scale of days to weeks. The term "Emotional" is meant to be evocative and should not be taken literally.

The 3rd level of sublimation, at which processes of need fulfillment subsume yourself and a up to few dozen people and play out on a scale of months to years. The term "social" is meant to be evocative and should not be taken literally.

The series of solutions a person has internalized in childhood for each sublimation level. As there are two sublimation levels which have not been fully resolved in modern society, there are 9 dispositions, of which 8 are pathologically aligned with Eros, Thanatos, or a mixture of the two.

The process of solve and unio by which a person can heal their pathology and transition from one of the eight pathological types to the one healthy type.

The most abstract sublimation level for which there is not an extant solution

The open, Thanatos aligned stage of civilizational progress. Individuals are inculcated Open and society takes a diffuse character. Declines into stagnation.

A pathological disposition.

The closed, Eros aligned stage of civilizational progress. Individuals are inculcated closed and society takes on a centralized character. Declines into atrocity.

A portable, moral ideology, usually religious in character, which combines the social technologies developed during the Thesis and Antithesis eras of a society's evolution into a system by which adults can alter their conditioning.