17 Midfoot Trauma: Lisfranc Injuries

An injury to the tarsometatarsal joint is known by the eponym “Lisfranc injury.” These types of injuries include sprains of the midfoot ligaments, fractures, or a combination of the two. Midfoot trauma including Lisfranc injuries are relatively rare, but when they occur they can be severe. Symptoms include marked pain, swelling, and inability to bear weight. Some Lisfranc injuries are subtle and can go undetected at first. Because these untreated injuries can be disabling, it is essential to diagnose them as they occur.

Structure and function

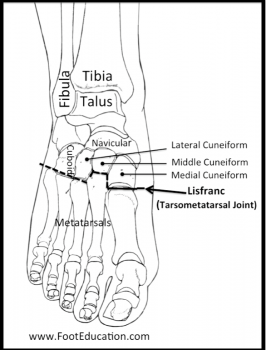

The midfoot (navicular, cuneiforms, and cuboid tarsal bones) meets the metatarsals at the tarsometatarsal joint, also known as the Lisfranc joint complex (Figure 1). This joint is stabilized by strong ligaments, particularly the plantar ligaments which support the arch and markedly limit motion through the joints of the midfoot. Bony congruence is also critically important to stability of the tarsometatarsal joint – namely, the articulation of the cuneiforms and bases of the metatarsals. The keystone of this arch is the base of the second metatarsal, which is tightly recessed between the medial and lateral cuneiforms, locking the tarsometatarsal complex and preventing medial/lateral translation (Figure 1). Thus, dislocation of the metatarsals or cuneiforms typically also involve fracture of the second metatarsal. Additional dynamic stability of the tarsometatarsal joint is offered by the posterior and anterior tibial tendons and peroneal tendons.

All of the bones of the midfoot are attached to their neighbors by ligaments with one exception: there is no ligament connecting the first and second metatarsal. This creates a point of weakness between the first and the other metatarsals. There is an oblique ligament, designated the Lisfranc ligament, which traverses from the plantar-lateral aspect of the medial cuneiform to the plantar-medial aspect of the second metatarsal. Biomechanical studies have shown the Lisfranc ligament to be significantly stronger and stiffer than the plantar and dorsal cuneometatarsal ligaments, making it the main stabilizer of the midfoot.

Patient presentation

Patients with acute Lisfranc injuries will present with a history of a traumatic injury to the foot. These injuries can be caused by a low-energy injury such as a twisting fall, or by a high-energy injury such as a fall from a height. Sporting activities that require the use of foot straps, such as windsurfing and horse-back riding seem to place people at high risk of this injury. It is also seen more commonly in football players: a force directed down onto the planted foot by a falling player or tackle from behind can lead to hyperplantarflexion at the Lisfranc joint. A similar force is created during high speed motor vehicle collisions, where the foot is often driven into the floorboard (hyperflexing it) as the driver attempts to brake to avoid the crash.

Gross subluxation or lateral deviation of the foot is rare with this injury occurring only in the most severe cases of Lisfranc injuries. As such, pain in the midfoot region, swelling and bruising on the center plantar surface, and pain with weight-bearing may be the only findings that suggest the diagnosis of Lisfranc injuries.

A Lisfranc injury may be stable or unstable. Stable Lisfranc injuries are characterized by a ligamentous injury that is not severe enough to allow the tarsometatarsal joints to displace. Stable Lisfranc injuries typically have no apparent fractures, or fractures that are non-displaced. However, stable Lisfranc injuries still cause significant discomfort because the ligaments of the midfoot are normally subject to marked forces (1-3 times greater than body weight) during normal standing and walking. Therefore, even stable injuries are painful and have a prolonged recovery period. Unstable Lisfranc injuries result in displacement of some or all of the tarsometatarsal joint with associated complete ligament disruption and/or significant fractures of the metatarsal base(s).

Objective evidence

On physical exam, Lisfranc injuries may be manifest as plantar ecchymosis – bruising along the sole of the midfoot (Figure 2). A diminished dorsalis pedis pulse (the artery courses over the proximal head of the second metatarsal) can indicate a more severe dislocation.

Palpation of the foot produces maximum tenderness at the base of the first and second metatarsals. If weight-bearing is even possible, one might see a gap between the big and second toe in the injured foot (the gap sign), as well as a convex bulge at the midfoot on the medial border.

Radiographs should include weight-bearing anteroposterior, lateral views, and 30-degree oblique views. These should be assessed for any fractures, dislocations, or incongruity of the tarsometatarsal joints. Obtaining a comparison image of the other foot is useful to have a reference for normal alignment.

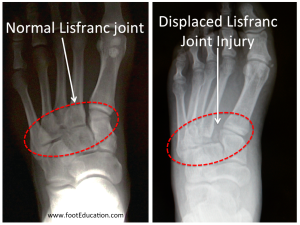

On review of the AP films, the space between the bases of first/second metatarsals and between the medial/middle cuneiforms should be closely examined. Alignment of the medial border of the second metatarsal/ middle cuneiform and the medial border of the first metatarsal/medial cuneiform should also be assessed (Figure 3). On lateral films, the superior border of the metatarsal base is normally aligned with the superior border of its corresponding tarsal, but when injured, the metatarsals may sometimes be shifted dorsally or plantar relative to their respective tarsal bone.

A radiographic finding pathognomonic of a Lisfranc injury is the “fleck sign” (Figure 4). This is produced by a bony fragment avulsed at the attachment of the Lisfranc ligament and lying between the bases of the first and second metatarsals.

Epidemiology

Lisfranc joint injuries are rare and frequently misdiagnosed. The incidence of Lisfranc fracture-dislocations are 1 in 55,000 persons per year, accounting for less than 1% of all fractures. Furthermore, as many as 20% of Lisfranc injuries are missed on initial radiographs.

Differential diagnosis

If there is concern about a midfoot injury, a navicular fracture, rupture or avulsion of the posterior tibial tendon should be considered. It is also possible to separate, or avulse, an accessory navicular (an “extra bone” seen in about 10% of the population), creating a painful prominence.

Red flags

Midfoot pain after trauma is a red flag symptom. It is often a manifestation of a Lisfranc injury. Pain and swelling in the midfoot following an acute injury should be considered a Lisfranc injury until proven otherwise.

Treatment options and outcomes

For stable injuries, immobilization is recommended. Patients are usually asked to be non-weight bearing or limited weight-bearing through the heel for 6 weeks. After 6 weeks, the patient can gradually increase activity levels. However, full recovery can take several months as the midfoot ligaments must heal enough to stabilize the midfoot joints during gait. An early accurate diagnosis of a Lisfranc injury is important for good functional outcome and proper management. An accurate outline of the prognosis is important for patients. Unlike an ankle sprain, a midfoot sprain (Lisfranc injury) will often take many months to fully recover and may be associated with residual symptoms.

Operative Treatment of Lisfranc Injuries

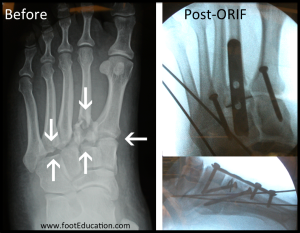

Surgery should be considered in unstable injuries. Surgery should be undertaken either immediately (before significant swelling occurs) or after allowing the swelling to settle – approximately 7 to 10 days after injury. Surgical fixation allows the bones and ligaments to be held in place for proper healing. This procedure involves reducing and fixing each affected tarsometatarsal joint with screws and/or a plate (Figure 5). The first metatarsal-medial cuneiform articulation is reduced and stabilized first, as this maneuver often reduces the second metatarsal-middle cuneiform joint (Lisfranc complex) as well. Reduction of the fracture-dislocation of the second metatarsal is essential, and firm opposition of the lateral border of the medial cuneiform to the second metatarsal allows for healing of Lisfranc’s ligament. A subsequent surgery to remove the hardware may be necessary.

If the diagnosis is delayed or the injury is associated with a complete disruption of the midfoot ligaments, arthrodesis (fusion of the bones making up the involved 1st-3rd tarsometatarsal joints) may be required to successfully address a Lisfranc injury. An arthrodesis (fusion) eliminates motion in the affected joint completely. Prospective randomized studies seem to suggest primary arthrodesis may result in better short-term and medium-term outcomes for unstable displaced Lisfranc injuries when compared to fixation. The rate of secondary surgeries (planned and unplanned, including hardware removal and salvage arthrodesis) are reduced with primary arthrodesis. However, it is unclear whether fixation offers better long-term functional result.

After surgery, a period of non-weight-bearing for 6 to 8 weeks is recommended. Weight-bearing is started while the patient is in the boot if the x-rays look appropriate after 6 to 8 weeks. A return to impact activities, such as running and jumping, may take six months or more. It takes at least a year and often much longer to achieve maximal improvement – and indeed some athletes never return to their pre-injury levels of sport after these injuries.

Even with excellent surgical reduction and fixation, midfoot arthritis may occur from damage to the cartilage. This can lead to chronic midfoot pain and may require fusion in the future. Post-traumatic arthritis is the most common complication (occurring in up to 50% of cases) of Lisfranc joint injury, which is related to the degree of comminution of the articular surface.

Common sequelae of Lisfranc injuries include late midfoot collapse (flatfoot deformity), metatarsalgia, posttraumatic arthritis. Post-traumatic midfoot arthritis and flatfoot deformity can occur in up to 50% of cases.

Miscellany

Jacques Lisfranc de St. Martin (1787-1847), a French Napoleonic-era physician, initially lent his name only to an operation: the Lisfranc amputation. This was an amputation of the foot at the tarsometatarsal joint, used to treat gangrene of the forefoot. Soldiers who fell from a horse with their feet stuck in the stirrup and injured their tarsometatarsal joint frequently, in turn, disrupted the dorsalis pedis artery. Although better diagnosis and treatment has obviated the need for amputations following tarsometatarsal joint injury, the surgeon’s name has remained linked to the tarsometatarsal joint. (Lisfranc amputations are still performed for gangrene, though these days the etiology is more commonly diabetes-related vascular disease.)

Key terms

Lisfranc injury, Lisfranc ligament, fleck sign, plantar ecchymosis, midfoot arthritis, Lisfranc open reduction internal fixation (ORIF)

Skills

Recognize the physical exam signs of a Lisfranc injury. Assess foot radiographs for the integrity of the tarsometatarsal joint.