6 De Quervains Disease

De Quervain’s disease is a common cause of pain at the base of the thumb and the radial side of the wrist. This condition is characterized by irritation of the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus, as they pass through their sheaths in the so-called “first compartment” on the dorsum of the wrist. The cause of de Quervain’s disease is often unknown, but repetitive grasping tasks and rheumatoid arthritis are associated with increased incidence. The use of a splint usually leads to relief, but injection with steroids, or failing that, surgical release of the tendon sheath may be needed.

Structure and function

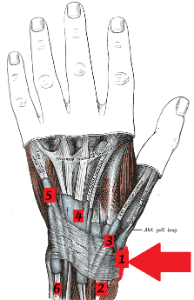

There are six compartments on the dorsal side of the wrist (as shown in figure 1).

- The first compartment (and the one involved in de Quervain’s disease) houses the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus. This compartment lies over the radial styloid

The other compartments are as follows:

- The second compartment holds the extensor carpi radialis longus and extensor carpi radialis brevis

- The third compartment holds the extensor pollicis longus

- The extensor indicis proprius and the extensor digitorum communis (to 4 fingers) are in the fourth compartment

- The fifth compartment has the extensor to the fifth finger, the extensor digiti minimi

- The extensor carpi ulnaris is in the sixth compartment.

All of these extensor tendons emanate from the forearm and cross the wrist. They are secured by the extensor retinaculum above and by the bones below. All have synovial tendon sheaths to keep them in place and to reduce friction.

Because these tendons are in an enclosed space, any process that makes the tendon larger or the surrounding tissue more confining will impede normal motion of the affected tendon.

De Quervain’s disease is frequently associated with attrition and degeneration of the affected tendons. Reactive swelling may be seen as well. In turn, there is resistance to gliding and pain.

The histopathology of de Quervain’s disease was studied by Clarke et al (PMID: 9888670). They reported that “the condition was not characterized by inflammation, but by thickening of the tendon sheath and most notably by the accumulation of mucopolysaccharide, an indicator of myxoid degeneration. These changes are pathognomonic of the condition and are not seen in control tendon sheaths.” They further stated “de Quervain’s disease is a result of intrinsic, degenerative mechanisms rather than extrinsic, inflammatory ones.”

Overuse, a direct blow to radial side of the wrist and repetitive grasping are all thought to cause de Quervain’s disease, but clearly not always does de Quervain’s disease follow these “inciting events.” In addition, there are cases with de Quervain’s disease with no known cause. In sum, the question of causality has not been answered definitively.

Pregnancy and rheumatoid arthritis are associated with increased incidence of clinically significant de Quervain’s disease.

It is possible that anatomic abnormalities, causing the tendon to take a less direct course or perhaps to be caught by a septum within the compartment, may be causal in a minority of cases.

Patient presentation

The chief complaint of de Quervain’s disease is pain on the thumb side of the wrist, worsened with grasping.

Swelling may be seen; if so, it is likely caused by an associated retinacular (ganglion) cyst.

Some patients notice a catching sensation as the tendons to the thumb are momentarily caught within their sheath.

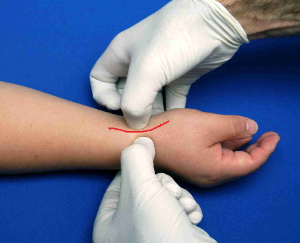

De Quervain’s disease can be confirmed clinically with Finkelstein’s test: in this test, the thumb is brought toward the ulnar side of the hand by the examiner, as shown below in Figure 2. A positive test is characterized by reproduction of pain at the distal radius.

Another variation is for and the patient to place the thumb under the other 4 (flexed) fingers. Then, with the thumb so stabilized, the examiner ulnar-deviates the hand, thereby stretching the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus tendons attached to the thumb.

(The extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus are muscles that cause radial abduction of the thumb away from the other fingers, in the plane of the palm. The provocative movement in Finkelstein’s test can be thought of as forced ulnar adduction with the tendons under tension.)

Objective evidence

Plain radiographs are generally not needed in diagnosing de Quervain’s disease, but can help rule out other processes including fractures (of the radial styloid or carpus) and arthritis.

Lab studies are likewise not part of the diagnostic work-up.

Epidemiology

Like most conditions that are diagnosed clinically, are self-limited and may have mild forms, de Quervain’s disease resists precise epidemiological measurement.

De Quervain’s disease is more common among women.

De Quervain’s disease is seen in pregnant women, and even more so in the immediate post-partum period.

Differential diagnosis

Thumb pain can be caused by osteoarthritis of the basal joints. (Note: arthritis and de Quervain’s disease frequently co-exist.)

Carpal tunnel could cause pain in the thumb, but would not be provoked by Finkelstein’s test and would typically involve other fingers.

So-called “intersection syndrome” i.e. pain at the intersection of the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis with the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis, can cause similar symptoms, though more proximal in the forearm.

Compression of the superficial branch of the radial nerve may cause symptoms in the area characteristic of de Quervain’s disease, but would not be affected by Finkelstein’s test.

Red flags

De Quervain’s disease has no red flags per se, but treatment with injections can lead to infection which must be detected promptly.

Treatment options and outcomes

The first line treatment includes rest, thumb splinting and NSAIDs. Splinting should keep the wrist neutral and the thumb slightly abducted.

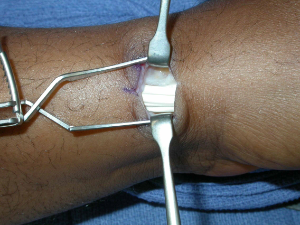

If splinting does not work (adequately), then injection into the first compartment with steroid may help (Figure 3 and 4). One mL of dexamethasone and 1 mL of lidocaine is a reasonable combination. The addition of the local anesthetic (lidocaine) can allow both the physician and patient to get an immediate sense if the medicine was placed correctly (anatomic variance may make it hard to be sure that an injection hit its target) and whether the treatment is apt to work.

Surgical release is reserved for those who fail all other modes of treatment. The goals of surgery include complete decompression (including multiple subcompartments within the “first compartment”) and avoidance of the radial sensory nerve.

Richie and Briner (PMID: 12665175) report “an 83% cure rate with injection alone.” Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had pain at the radial wrist, tenderness at the first dorsal wrist extensor compartment, and a positive Finkelstein test. Patients were considered cured if all three signs were obliterated.

Richie and Briner further report that the cure rate with injection alone “was much higher than any other therapeutic modality” including injection plus splinting (a manifestation of the healthful effects of stress, the authors posit). Interestingly, they found a 0% cure rate for rest or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Aside: this latter finding – which does not match common clinical experience — shows how difficult it is to assess a case series reporting on conditions that are diagnosed clinically. First, it may well be that rest will eliminate pain and tenderness, but not obliterate the Finkelstein test response. That “two out of three” outcome is probably not a clinical failure, though it is by these authors’ standard. Also, complete obliteration of signs and symptoms may not be needed for clinical success either. (The inventor of a non-invasive method to reduce back pain by 80% without complications will have a large fortune in no time.) Last, patients who were not given any affirmative treatment, but rather rest alone, will not benefit from any placebo effect either.

Risk factors and prevention

De Quervain’s disease seems to be caused by processes that cannot be avoided. As such, there is no meaningful program for prevention. That said, if a particular inciting event seems to increase symptoms, common sense would dictate trying to minimize that activity.

Miscellany

This condition is named after a Fritz Quervain, a Swiss physician perhaps more famous for his description of Giant Cell Thyroiditis. His name is pronounced something like “Care Van.”

Key terms

de Quervain’s, Finkelstein’s test, tendinitis

Skills

Able to perform Finkelstein’s test.