10 Finger and Hand Infections

The hand is susceptible to infection by virtue of its intimate contact with the outside world, its great surface area and its propensity for injury. That is, the hand is exposed frequently to infectious organisms, and these organisms are frequently given a point of entry.

The specialized anatomy of the hand, particularly the tendon sheaths and deep fascial spaces, create distinct pathways for infection to spread. In addition, even fully cleared infections of the hand can result in significant morbidity, including stiffness and weakness. For these reasons, early and aggressive treatment of hand infections is imperative.

In this section, specific hand infections will be considered:

- paronychia: infection of the folds of skin surrounding a fingernail

- felon: a purulent collection on the palmar surface of the distal phalanx

- flexor tenosynovitis: purulent material resides within the flexor tendon sheath.

- septic arthritis: infection in the joint space, often related to bite wounds

Paronychia

The paronychium is a small band of epithelium that covers the medial and lateral borders of the nail. The eponychium is a small band of epithelium that covers the proximal aspect of the nail.

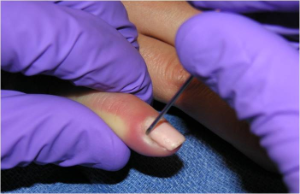

A paronychia (Figure 1) is an infection of the paronychium or eponychium. It is caused by minor trauma such as nail biting, aggressive manicuring, hangnail picking or applying artificial nails. Immunodeficiency, poor glycemic control, and occupations involving repeated hand exposure to water (e.g. dishwasher) are risk factors for the development of paronychia.

Tenderness and erythema of the nail fold at the site of infection will become evident within a few days of the inciting trauma. Progression to abscess formation is common.

Turkman et al described the “digital pressure test for paronychia”: A paronychia will appear as a blanched area when light pressure is applied to the volar aspect of the affected digit.

If left untreated, the paronychia can spread along the nail fold from one side of the finger to the other, or to beneath the nail plate.

Treatment for early cases includes warm water soaks and antibiotics. However, once a purulent collection has formed, treatment requires opening the junction of the paronychial fold and the nail plate (Figure 2). This is normally done with the bevel of an 18 gauge needle.

Acute paronychiae are usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus and are treated with a first-generation cephalosporin or anti-staphylococcal penicillin. Broader coverage is indicated if other pathogens are suspected. Chronic paronychiae may be caused by Candida albicans or by exposure to irritants and allergens.

Paronychiae may be prevented by avoiding behaviors such as nail biting, finger sucking, and cuticle trimming. Patients with chronic paronychia should be advised to keep their nails short and to use gloves when exposed to known irritants.

Felon

A felon is an abscess on the palmar surface of the fingertip. Bacteria are normally introduced via minimal penetrating trauma, such as a splinter.

The palmar aspect of the fingertip contains many osteocutaneous ligaments that connect the palmar skin of the fingertip to the distal phalanx. These ligaments prevent excessive mobility of the skin during pinch; they also maintain position of the cutaneous sensory endings and receptors to allow for identification of objects during grasp. The organization of these osteocutaneous ligaments form a relatively non-compliant compartment in the distal phalanx; thus, rather than expanding when pus is introduced, the compartment will simply increase in pressure.

Elevated compartment pressure results in significant pain relative to the (small) amount of pus. In addition, the gradient between capillary pressure and tissue pressure is decreased; the resulting decrease in perfusion can lead to tissue necrosis. Furthermore, because the osteocutaneous ligaments attach to the distal phalanx itself, osteomyelitis (infection of the bone) can occur.

Treatment involves surgical drainage and antibiotics. Incision and drainage is performed at the most fluctuant point. The incision should not cross the distal interphalangeal joint flexion crease (to prevent formation of a flexion contracture from scar formation) or penetrate too deeply (to prevent spread of infection from violating the flexor tendon sheath). Potential complications of excessive dissection to drain a felon include an anesthetic fingertip or unstable finger pad.

Antibiotic treatment should cover staphylococcal and streptococcal organisms. X-rays may be helpful to ensure that there is no retained foreign body.

Flexor tenosynovitis

In the fingers, a series of pulleys hold the tendons in close apposition to the bone, preventing bowstringing during flexion. There are a total of 8 pulleys overlying the finger flexor tendons and 3 pulleys overlying the thumb flexor tendon; these pulleys together are called the flexor tendon sheath.

In flexor tenosynovitis (Figure 3), the infection is within the flexor tendon sheath. This infection is particularly harmful because bacterial exotoxins can destroy the paratenon (fatty tissue within the tendon sheath) and in turn damage the gliding surface of the tendon. In addition, inflammation can lead to adhesions and scarring, and infection can lead to overt necrosis of the tendon or the sheath.

Although patients may not recall a specific history of trauma, flexor tenosynovitis is usually the product of penetrating trauma. Flexor tenosynovitis may be caused by inoculation and introduction of native skin flora (e.g., Staphylococcus and Streptococcus) or by more unusual organisms (e.g., Pasteurella and Eikenella) when there is a bite wound.

Flexor tenosynovitis can also have noninfectious causes such as chronic inflammation from diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis or other rheumatic conditions (e.g., psoriatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and sarcoidosis).

Kanavel described four classic signs of flexor tenosynovitis, as follows:

- Flexed posture of the digit.

- Fusiform (sausage-shaped, or tapering) swelling.

- Tenderness to palpation over the flexor tendon sheath.

- Pain over the flexor tendon sheath with passive extension of the finger

Anatomic relationships of flexor sheaths to deep fasical spaces should be kept in mind. Contiguous spread can result in a “horseshoe abscess”: from small finger flexor sheath to the thumb flexor sheath via connection between the radial and ulnar bursae.

If the diagnosis of flexor tenosynovitis is not clear, the patient may be admitted to the hospital for antibiotics, elevation of the affected hand, and serial examination. Non-operative treatment should be reserved for normal hosts. In patients with diabetes or any disease that may compromise the immune system, early surgical drainage is indicated even for suspected cases.

If the diagnosis of flexor tenosynovitis is established definitively, or if a suspected case in a normal host does not respond to antibiotics, surgical drainage is indicated (Figure 4). During this surgery, it is important to open the flexor sheath proximally and distally to adequately flush out the infection with saline irrigation. The distal incision is made very close to the digital nerve and artery as well as the underlying distal interphalangeal joint; it is important to avoid damage to these structures during surgery. Some surgeons will leave a small indwelling catheter in the flexor sheath to allow for continuous irrigation after surgery, but there is no conclusive evidence that this ultimately improves results.

Post-operative active and passive ROM exercises are recommended. Intravenous antibiotics should continue for an additional two or three days. (The duration of IV antibiotic administration as well as the need for oral antibiotics thereafter is determined by the intraoperative cultures and clinical response.)

Post-operative adhesions damage gliding surfaces and decrease active range of motion, and thus require tenolysis. Soft tissue necrosis and flexor tendon rupture are other relatively common complications.

Joint infection

The metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints are closed, relatively avascular spaces. Infection can reach the joint space via direct penetration or hematogenous spread.

Small (and ring) finger metacarpophalangeal joint infections in particular may result from a “fight bite,” where the patient strikes and an opponent in the mouth with a closed fist and the opponent’s tooth penetrates the joint and seeds it with oral flora. As with flexor tenosynovitis, a major risk of joint space infection is destruction of the gliding surface by bacterial exotoxins, which can compromise recovery of motion after the infection resolves.

A fight bite is at particularly high risk for complications, for the following reasons:

- the puncher may underestimate the severity of the wound

- the puncher may have been intoxicated (and sufficiently “medicated” to not feel pain)

- the puncher may attribute initial symptoms to bone pain from punch and not present for care until cellulitis is rampant

- the initial examiner may underestimate the severity of the wound, as it is usually small (the size of an incisor tooth or smaller, e.g. 3mm) with clean edges

- the human mouth has a high concentration of nearly 200 species of bacteria, many “unusual” anaerobes

- motion of the MCP joint to “shake off the pain” may drive saliva deeper into the tissue

- the extensor tendon and joint capsule are fairly superficial and may be violated with seemingly shallow wounds

- the extensor tendon and joint capsule are fairly avascular and thus unable to fight infection

Fight bites (Figure 5) should be meticulously irrigated, preferably with a formal debridement by a hand surgeon in the operating room. The laceration must not be closed in the ED.

Diagnosis of an established joint infection is often made by clinical examination. Patients will have swelling and erythema centered on the affected joint. Motion or axial loading of the joint will increase pain. Assessment of joint fluid for cell count, gram stain, and crystals (acute crystalline arthropathy such as gout can mimic a joint infection) can aid in the diagnosis, but it is often quite difficult to pass a needle into the narrow joint space and obtain an adequate sample. Serum markers of inflammation (such as white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C – reactive protein) are not typically elevated with an infection of a small joint of the hand. X-rays should be obtained to ensure that there is no fracture or retained tooth fragment.

Treatment consists of incision and drainage of the joint space. For the metacarpophalangeal joints of the fingers, the approach is normally dorsal through the long extensor tendon. In “fight bite” situations, there may be an indentation of the head of the metacarpal where it struck the tooth. For the interphalangeal joint, the approach is normally dorsolateral between the extensor mechanism dorsally and the collateral ligament laterally. Arthroscopic approaches have been described for the wrist and even the metacarpophalangeal joint, but an open approach is more commonly used.

General principles

- Open wounds must be irrigated to remove debris

- Closed abscesses must be incised and drained

- Devitalized tissue should be debrided

- Penetrating wounds require consideration of tetanus status

- Splinting the hand may enhance healing

- Patients with diabetes mellitus have more gram-negative infections and require broader antibiotic coverage

- Patients in an immunocompromised state may develop a hand infection from hematogenous spread from another site

- Unusual exposures lead to unusual bacteria: e.g. tropical fish aquarium workers, butchers, farmers.

Imaging

Patients suspected of having a hand infection will often undergo plain x-rays. The bony structures will typically appear normal except in very advanced infections involving the bone. Ultrasound can show loculated fluid collections, but is heavily dependent on the skill of the person performing the study. Magnetic resonance imaging, with or without gadolinium contrast, may show occult deep space infections if the clinical picture is not clear. Use of MRI is limited by cost as well as availability depending on when and where the patient is being evaluated.

For most cases, the diagnosis of infection is made by history and physical exam. X-rays are a rapid and cost effective way to identify bony changes and radiopaque foreign bodies. More complex imaging studies should be reserved for situations where the diagnosis remains unclear despite adequate examination and initial treatment, or if the patient does not respond to appropriate management.