Developing the Persuasive Speech: Appealing to an Audience

Persuasion only occurs with an audience, so your main goal is to answer the question, “how do I persuade the audience to believe my proposition of fact, value, or policy?”

To accomplish this goal, identify your target audience—individuals who are willing to listen to your argument despite disagreeing, having limited knowledge, or lacking experience with your advocacy. Because persuasion involves change, you are targeting individuals who have not yet changed their beliefs in favor of your argument.

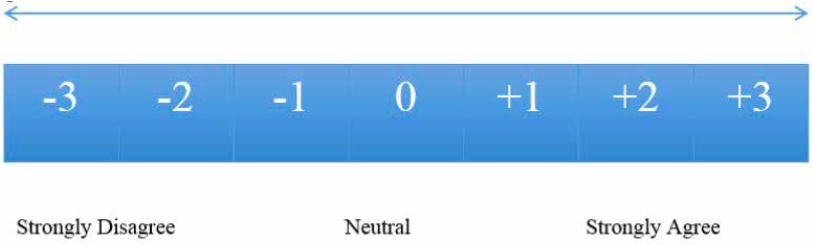

The persuasive continuum (Figure 13.1) is a tool that allows you to visualize your audience’s relationship with your topic.

Figure 13.1

The persuasive continuum views persuasion as a line going both directions. Your audience members, either as a group or individually, are sitting somewhere on that line in reference to your thesis statement, claim, or proposition.

For example, your proposition might be, “The main cause of climate change is human activity.” In this case, you are not denying that natural forces, such as volcanoes, can affect the climate, but you are claiming that human pollution is the central force behind global warming. To be an effective persuasive speaker, one of your first jobs is determining where your audience “sits” on the continuum.

+3 means strongly agree to the point of making lifestyle choices to lessen climate change (such as riding a bike instead of driving a car, recycling, eating certain kinds of foods).

+2 means agree but not to the point of acting upon it.

+1 as mildly in favor of your proposition; that is, they think it’s probably true but the issue doesn’t affect them personally.

0 means neutral, no opinion, or feeling uninformed enough to make a decision.

-1 means mildly opposed to the proposition but willing to listen to those with whom they disagree.

-2 means disagreement to the point of dismissing the idea pretty quickly.

-3 means strong opposition to the point that the concept of climate change itself is not even listened to or acknowledged as a valid subject.

Since everyone in the audience is somewhere on this line or continuum, persuasion means moving them to the right, somewhere closer to +3.

Your topic will inform which strategy you use to move your audience along the continuum. If you are introducing an argument that the audience lacks knowledge in, you are moving an audience from 0 to +1, +2, or +3. The audience’s attitude will be a 0 because they have no former opinion or experience.

Thinking about persuasion as a continuum has three benefits:

- You can visualize and quantify where your audience lands on the continuum

- You can accept the fact that any movement toward +3 or to the right is a win.

- You can see that trying to change an audience from -3 to +3 in one speech is just about impossible. Therefore, you will need to take a reasonable approach. In this case, if you knew most of the audience was at -2 or -3, your speech would be about the science behind climate change in order to open their minds to its possible existence. However, that audience is not ready to hear about its being caused mainly by humans or what action should be taken to reverse it.

As you identify where your target audience sits on the continuum, you can dig deeper to determine what values, attitude, or beliefs would prohibit individuals from supporting the proposition or values, attitudes, or beliefs that support your proposition. At the same time, avoid language that assumes stereotypical beliefs about the audience.

For example, your audience may value higher education and believe that education is useful for critical thinking skills. Alternatively, you may have an audience that values work experience and believes that college is frivolous and expensive. Being aware of these differing values will deepen your persuasive content by informing what evidence or insights to draw on and upon for each audience type.

Once you’re confident about where your audience is on the continuum and what values they hold, you can select the appropriate rhetorical appeals – ethos, pathos, and logos—to motivate your audience toward action. Yes, we’ve discussed these rhetorical appeals before, but they are particularly useful in persuasive speaking, so let’s review again.

Rhetorical Appeals

Ethos

“Danny Shine Speaker’s Corner” by Acapeloahddub. Public domain.

In addition to understanding how your audience feels about the topic you are addressing, you will need to take steps to help them see you as credible and interesting. The audience’s perception of you as a speaker is influential in determining whether or not they will choose to accept your proposition. Aristotle called this element of the speech ethos, “a Greek word that is closely related to our terms ethical and ethnic.”[1] He taught speakers to establish credibility with the audience by appearing to have good moral character, common sense, and concern for the audience’s well-being.[2] Campbell & Huxman explain that ethos is not about conveying that you, as an individual, are a good person. It is about “mirror[ing] the characteristics idealized by [the] culture or group” (ethnic),[3] and demonstrating that you make good moral choices with regard to your relationship within the group (ethics).

While there are many things speakers can do to build their ethos throughout the speech, “assessments of ethos often reflect superficial first impressions,” and these first impressions linger long after the speech has concluded.[4] This means that what you wear and how you behave, even before opening your mouth, can go far in shaping your ethos. Be sure to dress appropriately for the occasion and setting in which you speak. Also work to appear confident, but not arrogant, and be sure to maintain enthusiasm about your topic throughout the speech. Give great attention to the crafting of your opening sentences because they will set the tone for what your audience should expect of your personality as you proceed.

I covered two presidents, LBJ and Nixon, who could no longer convince, persuade, or govern, once people had decided they had no credibility; but we seem to be more tolerant now of what I think we should not tolerate. – Helen Thomas

Logos

Another way to enhance your ethos, and your chances of persuading the audience, is to use sound arguments. In a persuasive speech, the argument will focus on the reasons for supporting your specific purpose statement. This argumentative approach is what Aristotle referred to as logos, or the logical means of proving an argument.[5]

When offering an argument you begin by making an assertion that requires a logical leap based on the available evidence.[6] One of the most popular ways of understanding how this process works was developed by British philosopher Stephen Toulmin.[7] Toulmin explained that basic arguments tend to share three common elements: claim, data, and warrant. The claim is an assertion that you want the audience to accept. Data refers to the preliminary evidence on which the claim is based. For example, if I saw large gray clouds in the sky, I might make the claim that “it is going to rain today.” The gray clouds (data) are linked to rain (claim) by the warrant, an oft-unstated general connection, that large gray clouds tend to produce rain. The warrant is a connector that, if stated, would likely begin with “since” or “because.” In our rain example, if we explicitly stated all three elements, the argument would go something like this: There are large gray clouds in the sky today (data). Since large gray clouds tend to produce rain (warrant), it is going to rain today (claim). However, in our regular encounters with argumentation, we tend to only offer the claim and (occasionally) the warrant.

To strengthen the basic argument, you will need backing for the claim. Backing provides foundational support for the claim[8] by offering examples, statistics, testimony, or other information which further substantiates the argument. To substantiate the rain argument we have just considered, you could explain that the color of a cloud is determined by how much light the water in the cloud is reflecting. A thin cloud has tiny drops of water and ice crystals which scatter light, making it appear white. Clouds appear gray when they are filled with large water droplets which are less able to reflect light.[9]

| Table 16.1: The Toulmin Model | |

|---|---|

| Basic Argument | |

| data

I had a hard time finding a place to park on campus. |

claim

The school needs more parking spaces. |

| warrant

If I can’t find a place to park, there must be a shortage of spaces. |

|

| Argument with Backing | |

| data

Obesity is a serious problem in the U.S. |

claim

U.S. citizens should be encouraged to eat less processed foods. |

| warrant

Processed foods contribute to obesity more than natural or unprocessed foods. |

|

| backing

“As a rule processed foods are more ‘energy dense’ than fresh foods: they contain less water and fiber but more added fat and sugar, which makes them both less filling and more fattening.” (Pollan, 2007)[10] |

|

Logic is the beginning of wisdom, not the end. – Leonard Nimoy

“Dining Booth” by Wayne Truong. CC-BY.

The elements that Toulmin identified (see Table 16.1) may be arranged in a variety of ways to make the most logical argument. As you reason through your argument you may proceed inductively, deductively, or causally, toward your claim. Inductive reasoning moves from specific examples to a more general claim. For example, if you read online reviews of a restaurant chain called Walt’s Wine & Dine and you noticed that someone reported feeling sick after eating at a Walt’s, and another person reported that the Walt’s they visited was understaffed, and another commented that the tables in the Walt’s they ate at had crumbs left on them, you might conclude (or claim) that the restaurant chain is unsanitary. To test the validity of a general claim, Beebe and Beebe encourage speakers to consider whether there are “enough specific instances to support the conclusion,” whether the specific instances are typical, and whether the instances are recent.[11]

The opposite of inductive reasoning is deductive reasoning, moving from a general principle to a claim regarding a specific instance. In order to move from

general to specific we tend to use syllogisms. A syllogism begins with a major (or general) premise, then moves to a minor premise, then concludes with a

specific claim. For example, if you know that all dogs bark (major premise), and your neighbor has a dog (minor premise), you could then conclude that your

neighbor’s dog barks (specific claim). To verify the accuracy of your specific claim, you must verify the truth and applicability of the major premise. What evidence

do you have that all dogs bark? Is it possible that only most dogs bark? Next, you must also verify the accuracy of the minor premise. If the major premise is truly

generalizable, and both premises are accurate, your specific claim should also be accurate.

“Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling unit on fire” by US Coast Guard. Public domain.

Your reasoning may also proceed causally. Causal reasoning examines related events to determine which one caused the other. You may begin with a cause and attempt to determine its effect. For example, when the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, scientists explained that because many animals in the Gulf were nesting and reproducing at the time, the spill could wipe out “an entire generation of hundreds of species.”[12] Their argument reasoned that the spill (cause) would result in species loss (effect). Two years later, the causal reasoning might be reversed. If we were seeing species loss in the Gulf (effect), we could reason that it was a result of the oil spill (cause). Both of these claims rely on the evidence available at the time. To make the first claim, scientists not only offered evidence that animals were nesting and reproducing, but they also looked at the effects of an oil spill that occurred 21 years earlier in Alaska.[13] To make the second claim, scientists could examine dead animals washing up on the coast to determine whether their deaths were caused by oil.

Pathos

While we have focused heavily on logical reasoning, we must also recognize the strong role that emotions play in the persuasive process. Aristotle called this element of the speech pathos. Pathos draws on the emotions, sympathies, and prejudices of the audience to appeal to their non-rational side.[14][15] Human beings are constantly in some emotional state, which means that tapping into an audience’s emotions can be vital to persuading them to accept your proposition.[16]

One of the most helpful strategies in appealing to your audience’s emotions is to use clear examples that illustrate your point. Illustrations can be crafted verbally,

nonverbally, or visually. To offer a verbal illustration, you could tell a compelling story.  For example, when fundraising for breast cancer research, Nancy Brinker,

For example, when fundraising for breast cancer research, Nancy Brinker,

creator of Susan G. Komen for the Cure, has plenty of compelling statistics and examples to offer. Yet, she regularly talks about her sister, explaining:

Susan G. Komen fought breast cancer with her heart, body and soul. Throughout her diagnosis, treatments, and endless days in the hospital, she spent her time thinking

of ways to make life better for other women battling breast cancer instead of worrying about her own situation. That concern for others continued even as Susan neared

the end of her fight.[17]

Brinker promised her sister that she would continue her fight against breast cancer. This story compels donors to join her fight.

Speakers can also tap into emotions using nonverbal behaviors to model the desired emotion for their audience. In the summer of 2012, the U.S. House of

Representatives debated holding the Attorney General in contempt for refusing to release documents concerning a controversial gun-tracking operation.

Arguing for a contempt vote, South Carolina Representative Trey Gowdy did not simply state his claim; instead, he raised his voice, slowed his pace, and used

hand motions to convey anger with what he perceived as deception on the part of the Attorney General.[18] His use of volume, tone, pace, and hand gestures

enhanced the message and built anger in his audience.

Speech is power: speech is to persuade, to convert, to compel. It is to bring another out of his bad sense into your good sense. – Ralph Waldo Emerson

In addition to verbal and nonverbal illustrations, visual imagery can enhance the emotional appeal of a message. For example, we have all heard about the dangers of drugs, and there are multiple campaigns that attempt to prevent people from even trying them. However, many young adults experiment with drugs under the assumption that they are immune from the negative effects if they only use the drug recreationally. To counter this assumption regarding methamphetamines, the Montana Meth project combines controversial statements with graphic images on billboards to evoke fear of the drug (see the Montana Meth Project for some disturbing examples). Young adults may have heard repeated warnings that meth is addictive and that it has the potential to cause sores, rotten teeth, and extreme weight loss, but Montana Meth Project’s visual display is more compelling because it turns the audience’s stomach, making the message memorable. This image, combined with the slogan, “not even once,” conveys the persuasive point without the need for other forms of evidence and rational argument.

Appeals to fear, like those in the Montana Meth Project ads, have proven effective in motivating people to change a variety of behaviors. However, speakers must be careful with their use of this emotion. Fear appeals tend to be more effective when they appeal to a high-level fear, such as death, and they are more effective when offered by speakers with a high level of perceived credibility.[19] Fear appeals are also more persuasive when the speaker can convince the audience they have the ability to avert the threat. If audiences doubt their ability to avoid or minimize the threat, the appeal may backfire.[20]

I would rather try to persuade a man to go along, because once I have persuaded him, he will stick. If I scare him, he will stay just as long as he is scared, and then he is gone. – Dwight D. Eisenhower

David Brooks argues that “emotions are not separate from reason, but they are the foundation of reason because they tell us what to value.”[21] Those values are at the core of fostering a credible ethos. All of Aristotle’s strategies, ethos, logos, and pathos, are interdependent. The most persuasive speakers will combine these strategies to varying degrees based on their specific purpose and audience.

Ethics of Persuasion

“Speakers Corner Speaker 1987” by Deborah MacLean. Public domain.

In addition to considering their topic and persuasive strategy, speakers must take care to ensure that their message is ethical. Persuasion is often confused with another kind of communication that has similar ends, but different methods—coercion. Like persuasion, coercion is a process whereby thoughts or behaviors are altered. But in coercive acts, deceptive or harmful methods propel the intended changes, not reason. Strong and Cook contrasted the two: “persuasion uses argument to compel power to give way to reason while coercion uses force to compel reason to give way to power.”[22] The “force” that Strong and Cook mention frequently manifests as promises for reward or punishment, but sometimes it arises as physical or emotional harm. Think of almost any international crime film you have seen, and you are likely to remember a scene where someone was compelled to out their compatriots by way of force. Jack Bauer, the protagonist in the American television series 24, became an infamous character by doing whatever it took to get captured criminals to talk. Although dramatic as an example, those scenes where someone is tortured in an effort to produce evidence offer a familiar reference when thinking about coercion. To avoid coercing an audience, speakers should use logical and emotional appeals responsibly.

The pendulum of the mind alternates between sense and nonsense, not between right and wrong. – Carl Jung

Persuasive speakers must be careful to avoid using fallacies in their reasoning. Fallacies are errors in reasoning that occur when a speaker fails to use appropriate or applicable evidence for their argument. There are a wide variety of fallacies, and it is not possible to list them all here. Nine fallacies are described in the following section.

As we will learn in the following pages, we construct arguments based on logic. Understanding the ways logic can be used and possibly misused is a vital skill. To help stress the importance of it, the Foundation for Critical Thinking has set forth universal standards of reasoning. These standards can be found in Table 6.3.

| Table 6.3 |

|---|

| Universal Standards of Reasoning |

| All reasoning has a purpose. |

| All reasoning is an attempt to figure something out, to settle some question, to solve some problem. |

| All reasoning is based on assumptions. |

| All reasoning is done from some point of view. |

| All reasoning is based on data, information, and evidence. |

| All reasoning is expressed through, and shaped by, concepts and ideas. |

| All reasoning contains inferences or interpretations by which we draw conclusions and give meaning to data. |

| All reasoning leads somewhere or has implications and consequences. |

Logic and the Role of Arguments

“Sharia Law Billboard” by Matt57. Public domain.

We use logic every day. Even if we have never formally studied logical reasoning and fallacies, we can often tell when a person’s statement doesn’t sound right. Think about the claims we see in many advertisements today—Buy product X, and you will be beautiful/thin/happy or have the carefree life depicted in the advertisement. With very little critical thought, we know intuitively that simply buying a product will not magically change our lives. Even if we can’t identify the specific fallacy at work in the argument (non causa in this case), we know there is some flaw in the argument.

By studying logic and fallacies we can learn to formulate stronger and more cohesive arguments, avoiding problems like that mentioned above. The study of logic has a long history. We can trace the roots of modern logical study back to Aristotle in ancient Greece. Aristotle’s simple definition of logic as the means by which we come to know anything still provides a concise understanding of logic.[3] Of the classical pillars of a core liberal arts education of logic, grammar, and rhetoric, logic has developed as a fairly independent branch of philosophical studies. We use logic every day when we construct statements, argue our point of view, and in myriad other ways.

Understanding how logic is used will help us communicate more efficiently and effectively.

Defining Arguments

When we think and speak logically, we pull together statements that combine reasoning with evidence to support an assertion, arguments. A logical argument should not be confused with the type of argument you have with your sister or brother or any other person. When you argue with your sibling, you participate in a conflict in which you disagree about something. You may, however, use a logical argument in the midst of the argument with your sibling. Consider this example:

“Man and Woman Arguing” by mzacha. morgueFile.

Brother and sister, Sydney and Harrison are arguing about whose turn it is to clean their bathroom. Harrison tells Sydney she should do it because she is a girl and girls are better at cleaning. Sydney responds that being a girl has nothing to do with whose turn it is. She reminds Harrison that according to their work chart, they are responsible for cleaning the bathroom on alternate weeks. She tells him she cleaned the bathroom last week; therefore, it is his turn this week. Harrison, still unconvinced, refuses to take responsibility for the chore. Sydney then points to the work chart and shows him where it specifically says it is his turn this week. Defeated, Harrison digs out the cleaning supplies.

Throughout their bathroom argument, both Harrison and Sydney use logical arguments to advance their point. You may ask why Sydney is successful and Harrison is not. This is a good question. Let’s critically think about each of their arguments to see why one fails and one succeeds.

Let’s start with Harrison’s argument. We can summarize it into three points:

- Girls are better at cleaning bathrooms than boys.

- Sydney is a girl.

- Therefore, Sydney should clean the bathroom.

Harrison’s argument here is a form of deductive reasoning, specifically a syllogism. We will consider syllogisms in a few minutes. For our purposes here, let’s just focus on why Harrison’s argument fails to persuade Sydney. Assuming for the moment that we agree with Harrison’s first two premises, then it would seem that his argument makes sense. We know that Sydney is a girl, so the second premise is true. This leaves the first premise that girls are better at cleaning bathrooms than boys. This is the exact point where Harrison’s argument goes astray. The only way his entire argument will work is if we agree with the assumption girls are better at cleaning bathrooms than boys.

Let’s now look at Sydney’s argument and why it works. Her argument can be summarized as follows:

- The bathroom responsibilities alternate weekly according to the work chart.

- Sydney cleaned the bathroom last week.

- The chart indicates it is Harrison’s turn to clean the bathroom this week.

- Therefore, Harrison should clean the bathroom.

“Decorative toilet seat” by Bartux~commonswikiv. Public domain.

Sydney’s argument here is a form of inductive reasoning. We will look at inductive reasoning in depth below. For now, let’s look at why Sydney’s argument succeeds where Harrison’s fails. Unlike Harrison’s argument, which rests on assumption for its truth claims, Sydney’s argument rests on evidence. We can define evidence as anything used to support the validity of an assertion. Evidence includes testimony, scientific findings, statistics, physical objects, and many others. Sydney uses two primary pieces of evidence: the work chart and her statement that she cleaned the bathroom last week. Because Harrison has no contradictory evidence, he can’t logically refute Sydney’s assertion and is therefore stuck with scrubbing the toilet.

Defining Deduction

Deductive reasoning refers to an argument in which the truth of its premises guarantees the truth of its conclusions. Think back to Harrison’s argument for Sydney cleaning the bathroom. In order for his final claim to be valid, we must accept the truth of his claims that girls are better at cleaning bathrooms than boys. The key focus in deductive arguments is that it must be impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false. The classic example is:

All men are mortal.

Socrates is a man.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

We can look at each of these statements individually and see each is true in its own right. It is virtually impossible for the first two propositions to be true and the conclusion to be false. Any argument which fails to meet this standard commits a logical error or fallacy. Even if we might accept the arguments as good and the conclusion as possible, the argument fails as a form of deductive reasoning.

A few observations and much reasoning lead to error; many observations and a little reasoning to truth. – Alexis Carrel

Another way to think of deductive reasoning is to think of it as moving from a general premise to a specific premise. The basic line of reasoning looks like this:

This form of deductive reasoning is called a syllogism. A syllogism need not have only three components to its argument, but it must have at least three. We have Aristotle to thank for identifying the syllogism and making the study of logic much easier. The focus on syllogisms dominated the field of philosophy for thousands of years. In fact, it wasn’t until the early nineteenth century that we began to see the discussion of other types of logic and other forms of logical reasoning.

Logic: the art of thinking and reasoning in strict accordance with the limitations and incapacities of the human misunderstanding. – Ambrose Bierce

It is easy to fall prey to missteps in reasoning when we focus on syllogisms and deductive reasoning. Let’s return to Harrison’s argument and see what happens.

Considered in this manner, it should be clear how the strength of the conclusion depends upon us accepting as true the first two statements. This need for truth sets up deductive reasoning as a very rigid form of reasoning. If either one of the first two premises isn’t true, then the entire argument fails.

Let’s turn to recent world events for another example.

In the debates over whether the United States should take military action in Iraq, this was the basic line of reasoning used to justify an invasion. This logic was sufficient for the United States to invade Iraq; however, as we have since learned, this line of reasoning also shows how quickly logic can go bad. We subsequently learned that the “experts” weren’t quite so confident, and their “evidence” wasn’t quite as concrete as originally represented.

Defining Induction

Inductive reasoning is often thought of as the opposite of deductive reasoning; however, this approach is not wholly accurate. Inductive reasoning does move from the specific to the general. However, this fact alone does not make it the opposite of deductive reasoning. An argument which fails in its deductive reasoning may still stand inductively.

Unlike deductive reasoning, there is no standard format inductive arguments must take, making them more flexible. We can define an inductive argument as one in which the truth of its propositions lends support to the conclusion. The difference here in deduction is the truth of the propositions establishes with absolute certainty the truth of the conclusion. When we analyze an inductive argument, we do not focus on the truth of its premises. Instead, we analyze inductive arguments for their strength or soundness.

Another significant difference between deduction and induction is inductive arguments do not have a standard format. Let’s return to Sydney’s argument to see how induction develops in action:

- Bathroom cleaning responsibilities alternate weekly according to the work chart.

- Sydney cleaned the bathroom last week.

- The chart indicates it is Harrison’s turn to clean the bathroom this week.

- Therefore, Harrison should clean the bathroom.

What Sydney does here is build to her conclusion that Harrison should clean the bathroom. She begins by stating the general house rule of alternate weeks for cleaning. She then adds in evidence before concluding her argument. While her argument is strong, we don’t know if it is true. There could be other factors Sydney has left out. Sydney may have agreed to take Harrison’s week of bathroom cleaning in exchange for him doing another one of her chores. Or there may be some extenuating circumstances preventing Harrison from bathroom cleaning this week.

You should carefully study the Art of Reasoning, as it is what most people are very deficient in, and I know few things more disagreeable than to argue, or even converse with a man who has no idea of inductive and deductive philosophy. – William John Wills

Let’s return to the world stage for another example. After the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, we heard variations of the following arguments:

- The terrorists were Muslim (or Arab or Middle Eastern)

- The terrorists hated America.

- Therefore, all Muslims (or Arabs or Middle Easterners) hate America.

“1993 Word Trade Center bombing” by Bureau of ATF 1993 Explosives Incident Report. Public domain.

Clearly, we can see the problem in this line of reasoning. Beyond being a scary example of hyperbolic rhetoric, we can all probably think of at least one counter example to disprove the conclusion. However, individual passions and biases caused many otherwise rational people to say these things in the weeks following the attacks. This example also clearly illustrates how easy it is to get tripped up in your use of logic and the importance of practicing self-regulation.