3

“Metaphors have also been shown to affect behavior. For instance, metaphor-based

interventions – describing the brain as a ‘muscle’ that ‘grows’ with practice – can encourage

students to adopt an incremental, rather than

fixed, theory of intelligence” (Thibodeau, Hendricks, & Boroditsky, 2017).

Language plays an important role in all aspects of life, and pro-environmental behavior (PEB) is no exception. Language can have effects on PEB in multiple domains of influence: written or spoken language used to self-reflect, conversations between individuals, or messaging through advertisements, films, or images. By understanding the research behind language and its effect on self-concept, motivation, and specifically PEB, these concepts can be applied to daily life in order to increase PEB by choosing to produce and consume language in pro-environmental ways. Words affect how we think about ourselves and others, treat other people, decide what’s important and what’s not, and how we decide what to do or not to do. For example, pro-environmental messages can have very different effects on people depending on

whether they are more positively or negatively worded. Research interestingly finds that PEB advertisements with lower-fear appeals actually brought about more fear and positive intentions for PEB in participants, while high-fear advertisements had the opposite effect (Mei-Fang, 2016). Maybe this shows how important it is to not be too hard on ourselves when thinking about future PEB. Regardless, this is just one example of how words play such a vital role in determining whether we will enact more or less PEB.

Having a better understanding of your own thoughts, motives, feelings and goals is important for better life satisfaction, health, and even academic achievement (Pennebaker & Graybeal, 2001). Influential research by Pennebaker and Graybeal (2001) shows that even brief exercises where participants wrote or talked about their trauma resulted in less physical illness later on! This is not an uncommon finding. Other researchers have found similar results, both in healthy people and those with long-term health conditions. Writing and talking about our deep desires and thoughts doesn’t just have impacts on biological health, but also cognitive skills. For example, Pennebaker and Graybeal talk about research which linked “writing about emotional topics” to “improved grades among college students and faster acquisition of new jobs among unemployed workers” (2001, 91). Word choice when writing about yourself is another important factor in determining health and behavior as well. Pennebaker & Graybeal’s research also shows how using causal words, like “because” and “since,” as well as insight words, like “understand” and “realize” lead to better health outcomes (2001).

This directly applies to this project’s workbook exercises and ways to consciously increase PEB in your life. To become motivated enough to really increase PEB and learn more about the environment, it is totally necessary to get to a deep and personal level in the form of self-expressive writing, and being conscious about what words you’re using to talk about yourself. For example, talking about situations when you better understood the severity of the climate crisis or writing about why you want to pursue certain PEB are based on Pennebaker & Graybeal’s research and will help increase the frequency of PEB.

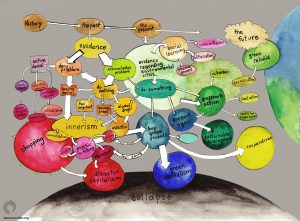

Other research shows that the ways metaphors are used have significant impacts on people’s behavior as well (Thibodeau et al., 2017). Metaphors can be used as wise interventions to change certain behaviors. The authors talk about “describing the brain as a ‘muscle’ that ‘grows’ with practice,” and how it “can encourage students to adopt an incremental, rather than fixed, theory of intelligence” (852). Thiboudeau et al. discuss how target and source domains in metaphors can be used strategically. For example, when saying that climate change (the target domain) is a war as opposed to a race (source domains), the war metaphor leads to higher willingness to change behavior, likely because of the cultural relevance and importance of war (Thibodeau et al., 2017). This can be applied to how we think about climate change as well as the effectiveness of external messages on our amounts of PEB.

Research specific to communication’s effect on PEB shows that motivation to take on such abstract issues is caused by emotional personal experience (Zaval & Cornwell, 2016). This is consistent with previous research discussed in this project, showing that to change our behavior, we must do a deep-dive into our emotional motivations. This ties in to language because to change amounts of PEB long-term, we must use language that connects deep emotions to issues of the environment. For the workbook exercises, this means that when you are prompted to do written reflections (e.g., write about the last time you did something good for the environment and how it made you feel), it is most important that you focus on how you felt, not just the behavior you completed. It might seem counterintuitive to focus on ourselves when thinking about the environment, but it is challenging–and almost impossible–to really tackle a big, abstract problem without making personal connections.

Writing about the self in relation to the environment is not the only way we can consciously use language to affect PEB. How we talk about the environment to others also plays a role in environmental self-perception and PEB, and–if used correctly–can motivate others to participate in PEB as well. Imagine a situation where you are talking to your friend Charlie about how you’ve started hanging up your clothing to dry instead of using the dryer in order to reduce electricity consumption. Instead of just talking about it in cold, hard facts, relating it to personal emotions is more strategic. For example, bringing up how it makes you feel like you’re actually having a positive impact on the world, or how small PEB are actually so much easier than anxiety would lead you to assume, will not only impact the likelihood of you repeating that PEB, but will also increase Charlie’s likelihood to do the same thing.

Lastly, metaphors can be used strategically to increase our and others’ PEB. When doing self-reflection exercises related to the environment, either in this workbook or in other settings, using metaphors that relate climate change to source domains that have cultural importance can increase PEB. For example, saying that “climate change is a war that needs to be won soon,” or “climate change is like a house on fire” poses the issue as something serious and urgent that needs to be addressed immediately by the individual. We can use these metaphors both in conversation with others, as well as written and mental self-reflection, to reiterate the severity and importance of climate change.

All this research on motivation, the Self Memory System (SMS), and language shows how important intention is in increasing PEB. In order to make long-lasting behavioral change, we must be mindful and intentional about what interventions we use. By keeping these principles in mind, you can feel confident that you are making smart, informed decisions that will help yourself and the environment–and hopefully others, if you encourage your circle of influence to do the same. Remember, climate change is an urgent, time-sensitive issue that all of us can contribute to reducing. Increasing your own PEB is not the only thing of concern here, expressing how important the issue is to others is of equal importance.

Chapter References

Mei-Fang, C. (2016). Impact of fear appeals on pro-environmental behavior and crucial determinants. International Journal of Advertising, 35(1), 74-92.

Pennebaker, J.W., & Graybeal, A. (2001). Patterns of natural language use: Disclosure, personality, and social integration. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(3), 90-93.

Thibodeau, P.H., Hendricks, R.K., & Boroditsky, L. (2017). How linguistic metaphor scaffolds reasoning. Trends in Cognitive Science, 21(11), 852-863.

Zaval, L., & Cornwell, F.J. (2016). Effective education and communication strategies to promote environmental engagement: The role of social-psychological mechanisms. Global Education Monitoring Report. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization.