2

“Imagine that you are moving house and all your belongings have already been

packed up when you find a bottle of a highly volatile liquid (such as ethyl ether

or white spirit) close to the door as you leave the empty house. What would you

do? Leave it there? Throw it in the trash container in front of the house? Take it

along in the car to your new home? What would your decision depend on?”

(Lindenberg & Steg, 2007)

This chapter gets into the deep mental processes behind forming pro-environmental goals and behavior. The Self-Memory System (SMS), an important psychological concept, is the intersection of self and autobiographical memory (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000). Autobiographical memory is memory about oneself, and is very important to self-identity (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce). When reminiscing about the past, you can do so at three levels of specificity: (1.) Lifetime periods, (2.) General events, and (3.) Event-Specific Knowledge (ESK)(Conway et al., 2000). Lifetime periods are the cultural and social knowledge within a given age cohort, but can also be specific periods of time (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce). Different lifetime periods can also overlap. For example, one lifetime period might be “when I was in high school,” but another might be “when I worked at Subway from ages 17-19.” These are two distinct lifetime periods, but they overlap. General events can be either a singular event or a series of events, and are more specific than lifetime periods. Examples of general events are “first environmental protest” or “working for Greenpeace.” Conway describes ESK as important imagery in autobiographical knowledge; for example, in a memory about participating in an environmental protest, the ESK would be the mental image of the sign proclaiming “NO to the Dakota Access Pipeline!” and the imagery of the specific people who were there with you. The more ESK present in a memory, the more vivid it is.

The self is highly connected to autobiographical memory. Conway and Pleydell-Pearce state that “the self, and especially the current goals of the self, function as control processes that modulate the construction of memories” (p. 264). Therefore, the self and memory are inherently intertwined. Conway and Pleydell-Pearce also refer to self as the “working self” in order to denote how the self interacts with working memory, which is the limited amount of information the mind can keep in the background for quick access (p. 265). The self and working memory work as control processes to create goals that affect thoughts and behaviors (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce). As the self creates goals, it can access certain autobiographical memories that are relevant to the goal at hand, in hand shaping the self. This is what constitutes the SMS. Using the working self mental mechanism, the SMS selects appropriate autobiographical knowledge–what you know about yourself–to give you an ongoing and coherent sense of self (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000). The two levels (working self and autobiographical knowledge) interact in complex ways but can also operate by themselves (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce). For the SMS to operate, though, both must be functioning at the same time.

However, the SMS is more complex than just the connection of working memory and self. Conway and Loveday describe the SMS of being composed of three levels: the working self, autobiographical memory, and episodic memory (2014). The first level, the working self, includes the conceptual self, which consists of self-perception, narratives, and “beliefs-values-attitudes,” and the goal system, which covers goals, plans, and projects (Conway & Loveday, 2014). The second level, autobiographical memory, combines lifetime periods and general events, which can be used to recall memories from the third level, episodic memory (Conway & Loveday, 2014).

Autobiographical knowledge and the working self affect each other directly. The working self creates goals, but if those goals are not in-line with knowledge about oneself, there will be conflict within the SMS; this needs to be remedied by either changing self-perception or changing autobiographical knowledge (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000). Therefore, the working self changes autobiographical memory, while autobiographical memory informs and solidifies perceptions of self. For example, being a protestor at an anti-Dakota Access Pipeline rally supports your sense of self as an activist, which yet again reinforces the likelihood of repeating similar behaviors again. The working self is affected by external influences, and it’s important to understand how the SMS works in social and cultural contexts. Autobiographical memories are about one’s personal experiences, but those experiences involve other people and situations created by the external world. That’s why lifetime periods are so important to someone’s SMS, because even within cultures and subcultures, generations experience different media, norms, values, and beliefs.

As previously mentioned, the SMS is heavily involved in setting and achieving goals, but this doesn’t just mean what we commonly think of as goals, such as wanting to run a marathon by the end of the year. Anything the self desires to do or pursues is a goal, and a variety of mental processes, primarily included in the SMS, are responsible for this. Something interesting that Conway and Pleydell-Pearce (2000) point out is that some researchers suggest “that autobiographical memories are primarily records of success or failure in goal attainment” (p. 266). This means that goals might be far more important to self-perception and memory than initially considered. The working self’s current important goals (like eating less meat) cause certain memories or pieces of autobiographical knowledge to come to the forefront (such as previous memories of feeling guilt when eating meat).

Goals, however, seriously vary over lifetimes—let alone every day. For example, an infant’s needs and goals are so drastically different even from that of a 10-year-old, that autobiographical knowledge about the experience of being an infant isn’t likely to be retrieved by the SMS; this is probably why none of us can remember much from before the age of five or so (Conway et al.). In the same way, a previous small goal in many environmentally-conscious people’s lives was to bring reusable cups to coffee shops and other businesses that sell beverages, in order to reduce paper and plastic waste. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, reusable cups are no longer allowed to be used at businesses for safety reasons. When we’re eventually allowed to bring reusable cups back again, how many people will actually do so, or will they refrain because of pandemic concerns? For those that decide to bring their cups back, this research on the SMS suggests that it will be much more difficult to remember to do so—think back to the beginning of the pandemic when most people struggled to remember to bring a mask along when leaving the house. Whether or not ditching reusable cups bothers you (I sure hate having to use throw-away cups), it shows how individual and group SMS-driven goals can be totally overhauled and difficult to re-implement when the situation changes.

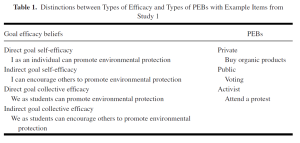

Pro-environmental behavior (PEB) is no exception from goal setting and the SMS, as the above example shows. Hamann and Reese (2020) break down PEB into three categories that have different motivations: “private-sphere environmentalism, nonactivist behavior in the public-sphere, and activist behavior” (p. 37).

Figure 1 provides examples of what the authors call “goal efficacy beliefs,” which are beliefs about individual and collective ability to help the environment. It’s important to understand that PEB goal-setting involves all of these levels: direct and indirect self-efficacy, as well as direct and indirect collective self-efficacy. On first glance, we might think of goal efficacy beliefs as only direct goal self-efficacy, like “by biking to work today instead of driving, I reduced my carbon footprint, which helped protect the environment, and also got some exercise in.” These are both goals centered around the action of the self and only the self, but goals to encourage others to do the same thing or work on a collective level make up the different levels of PEB that can help promote greater environmental protection (Hamann & Reese, 2020).

Lindenberg and Steg (2007) discuss three different types of goal frames and how they relate to PEB: hedonic goals frames (motivated by feel-good emotions that are a consequence of the action), gain goal frames (motivated by reducing costs), and a normative goal frame (motivated by appropriate behaviors). Normative goal frames are most likely to result in PEB, as one’s normative view of whether PEB are necessary or not strongly influences likelihood of the behavior (Lindenberg & Steg). This is likely the most effective goal frame for PEB because normative goals represent one’s beliefs, values, and attitudes, instead of just focusing on cost-benefit analysis (in the case of gain goal framing) or whether the action brings direct pleasure (in the case of hedonic goal framing). Normative goals are directly intertwined with the self and autobiographical knowledge; one’s normative assessments of the world, what should or ought to be, are created by the self.

Boomsma et al. (2016) talk about the differences of pro-environmental goals in relation to their length; they say that long-term goals are often too abstract and are not achieved, while short-term goals rely on recent experience and working memory that are more likely to be motivational. However, they make a very important point: long-term goals are achievable, too, it just requires a little more work and planning. By “forming implementation intentions or specific behavior plans,” long-term goals become more salient and easily accessible, and therefore more likely to be carried out (Boomsma et al.). This can occur by internalizing messages and, more vividly, through environmental imagery (Boomsma et al.). Boomsma et al.’s research shows that being shown environmental imagery leads to vivid recall of ESK, as well as formation of pro-environmental goals and PEB. This is important because it shows that even being shown images about the environment directly affects the SMS and causes us to make memories, goals, and even new behaviors—just caused by imagery.

This research shows that the SMS is inextricably intertwined with goal-setting and PEB, and is the main set of mental processes responsible for carrying out PEB. How does this relate to everyday life? By understanding the different type of goal framing and which is the most accurate, how setting goal intentions can result in more PEB, and how the SMS works in general, we can use our psychological scientific knowledge to affect change in both ourselves and others. Using less single-use plastic or consuming less animal products might seem daunting on the surface, but by applying psychological knowledge, they can become more accessible and easier to implement.

Chapter References

Boomsma, C., Pahl, S., and Andrade, J. (2016). “Imagining change: An integrative approach toward explaining the motivational role of mental imagery in pro-environmental behavior.” Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1-14.

Conway, M.A., and Pleydell-Pearce, C.W. (2000). “The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system.” Psychological Review, 107(2), 261-288.

Conway, M.A., and Loveday, C. (2014). “Remembering, imagining, false memories & personal meanings.” Consciousness and Cognition, 33, 574-581.

Hamann, K.R.S., and Reese, G. (2020). “My influence on the world (of others): Goal efficacy beliefs and efficacy affect predict private, public, and activist pro-environmental behavior.” Journal of Social Issues, 76(1), 35-53.

Lindenberg, S., and Steg, L. (2007). “Normative, gain and hedonic goal frames guiding environmental behavior.” Journal of Social Issues, 63(1), 117-137.