6 Behind on the Boom

1887 to 1892

___________________

“Over the canvas the newspaper correspondent flung his paint-pots of adjectives more lavishly and recklessly than ever and Eastern editors believed his extravagant nonsense and wrote editorials that still further increased the number of crazy pilgrims.”

— T.S. Van Dyke writing in Millionaires of a Day about the outsiders drawn to Los Angeles’ 1880s real estate boom

Tina’s fortune allowed Grif to control even more property and dabble further in real estate just as Los Angeles was reaching the height of a land boom it had never seen before. Such was the frenzy that outsiders descended on the city as “flies upon a bowl of sugar,” the 1889 Illustrated History of Los Angeles recounted. Locals and new arrivals embraced the term “boom” as if it had no downside. “Of all the booming booms in the city of San Bernardino,” proclaimed one newspaper ad that ran for several weeks, “the boomiest boom is the boom of the Hart Tract.”[1]

It even became a verb, so instead of developments being built, they were boomed. Boyle Heights, for example, was boomed thanks to its vicinity to the Santa Fe railway depot. A downtown neighborhood that many years later fell into decay, its best lots jumped from $150 to $10,000. There and across the region, people would stand in line overnight to get a place at the next day’s auction of a new tract. “When a tract was laid out as a townsite the first thing usually done was to build a hotel,” the Times recounted on December 4, 1891. “Cement sidewalks, brick blocks, a public hall and a street railroad soon followed. A miniature city appeared like a scene conjured up by Aladdin’s lamp where, a few months ago, the jack-rabbit sported and the coyote howled. Such a scene of transformation had never before been witnessed in the world. Old settlers, who had declared that land was dear at $5 an acre, looked aghast to see people tumbling over each other to secure lots at $500 each.”

In all, 60 new towns were created — on paper. By 1889, nearly two years after the peak, those “towns” had 79,350 lots but only 2,351 inhabitants — a reflection that most of the speculators never intended to live in those far-flung areas, they just wanted to buy and then quickly sell for a big profit.[2] The scheme worked for a few years, enough time to transform Los Angeles like never before.

But how did the Boom — and yes, it was worthy of a capital B — even come to pass? The foundation was laid by the railroad. Actually, two railway companies. The first to connect Los Angeles to the rest of the country was the Southern Pacific, in 1876. When the Santa Fe arrived in 1885 it became a turf war and the beneficiaries would be land speculators, tourists and potential home buyers. During the six-month war that started in mid-1886, a one-way ticket from Kansas City — the hub for rail trips across the continent — that had been $100 could be had for $5. There was even one day where it dropped to $1.[3]

Within the city, the magic of electricity was powering trolleys and revolutionizing local travel — and soon it allowed developers to extend Los Angeles miles out in any direction the rails went.

Having rails wasn’t enough, though, so cheerleaders helped sell Los Angeles to the rest of the United States. The railways hired writers to build up Southern California, some describing it as “Our Italy” or “The Land of Sunshine”, a moniker later turned into a booster magazine. Fruit growers had beautiful designs made for the crates shipping their goods back east — idyllic images like oranges dangling from flowering trees and the snow-capped San Gabriel Mountains in the distance.

Palms were planted as well to sell an exotic, Mediterranean lifestyle. They framed postcards and the most elaborate landscapes of these non-native plants became tourist attractions.

The Times did its part, too. In 1885, it started publishing a Mid-Winter Number that was sent back east and handed out for free — seducing settlers with sunny charm, pretty orange groves and the health benefits of a mild winter away from urban stench.

An article on “Our Climate” in that first edition was written by three local doctors who agreed that “the key” was that Los Angeles “has a warm sun and a cool air … one picks ripening figs and bananas grown in his own dooryard, and then goes to sleep under a blanket. The warm, yet not debilitating day, furnishes one of the requisites in a climate for invalids; the cool, restful night, with its possibilities of refreshening sleep, furnishes the other.”

Some called it the “California Cure” and the message was simple: Send us your sick, especially those with consumption, which we today know as tuberculosis, a lung disease spread by Industrial Age pollution. Others would benefit too, the doctors argued, from people with “an overtaxed or deranged nervous system” to those “who resist poorly the extremes of heat or cold.” In short, just about anyone.

Not that all were welcome. The Times, and more to the point its owner Harrison Gray Otis, wanted only the best American and European stock. The 1886 Mid-Winter Number, after listing what types of immigrants were welcome, listed who need not apply. “Dudes, loafers, paupers” topped that list, which also included “cheap politicians”, “people who have no means and no situation assured”, and “men with shady reputations ‘Back East’.”

Previous to the rail war, visitors had typically been well-to-do East Coast and Midwest businessmen, often with family in tow, fleeing bitterly cold winters. That contingent appeared, as it had for several years, during the winter of 1886 but now it was joined by thousands more.

Some were tourists, lookie-loos who didn’t have the money to buy property, but many others were well-off and, even if they hadn’t intended to buy during their visit, often became enchanted once they arrived. Moreover, these were not the previous generation of settlers in wagon trains. “Nowhere else in the world had such a class of settlers been seen,” wrote T.S. Van Dyke in Millionaires of a Day, a hilarious reflection on how absurd the Boom looked in hindsight. “Emigrants coming in (rail) palace-cars instead of ‘prairie schooners,’ and building fine houses instead of log shanties, and planting flowers and lawn-grass before they planted potatoes or corn.”

Some 35,000 dreamers from the Midwest and East were seduced into moving to the region by cheap train tickets and the booster campaign promising sun, sea and lots of land to farm. And those were just the new residents — tourists were 10 times that. In 1887 alone, 120,000 Americans visited, many looking to put down roots or at least buy property during what became known as the Boom of the Eighties.[4]

It made for an odd, and often comical, experience as Van Dyke masterfully described in 1890. “Faster and faster on every train came more men and more money,” he wrote. “Professional boomers” from earlier speculation in the Midwest and San Francisco made their way as well, joining the local land agents, and soon there were 2,000 salesmen jammed in storefronts across downtown and near the train stations. “The silk hat beamed over many a fossiliferous skull,” Van Dyke wrote, “and shining new buggies dashed here and there with real-estate speculators and agents who for years had gone on foot.”

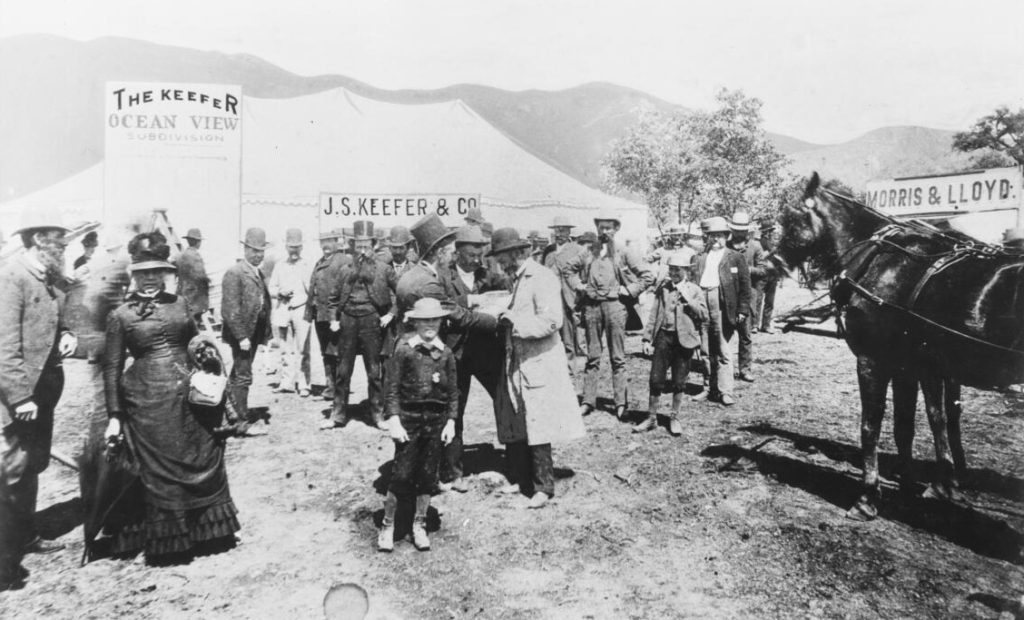

The sales pitches often involved a brass band, a free ride to the tract, a free lunch/desert and, of course, free California wine to open wallets. The Los Angeles Tribune on April 24, 1887, thus described one such event for the proposed town of Gladstone (which, by the way, never materialized): “Early risers were assailed by noises preceding from the throats of wind instruments, together with bewildering sounds of trumpet and cymbal. What was it? A large wagon, carriage or omnibus containing a full brass band and decorated on all sides with immense banners bearing the inscription ‘Gladstone’.” The wagon was followed by four buggies quickly engulfed by “a howling, raging mob of dabblers and dealers in real estate… Each car was loaded with swarms of people, old and young, male and female, and not one of them a respecter of persons other than themselves.”

Such was the frenzy that developers could auction lots knowing that people would outbid each other to get what they thought was a bargain. Those free meals and wine were often followed by an auctioneer whipping up the crowd with a little help from sales associates hidden among the guests and ready to bid if things slowed down.

Feeding the boom were East Coast and Midwest journalists who stepped off a train and into the frenzy. “Over the canvas the newspaper correspondent flung his paint-pots of adjectives more lavishly and recklessly than ever,” Van Dyke recalled, “and Eastern editors believed his extravagant nonsense and wrote editorials that still further increased the number of crazy pilgrims.”

The focus on speculation meant people spent less time actually doing productive things. Many a farmer neglected his land to join the frenzy. Los Angeles soon went from self-sufficiency to buying eggs, butter and chickens from the Midwest. The Los Angeles Manufacturing Association, launched in 1885 to help jump start local industry, shut down during the Boom for lack of interest.

Business Before Honeymoon

Where was Grif during all of this? Well, he was busy courting and then marrying Tina. It’s possible he initially thought all the speculation was beneath him, but he could also see the fortunes being made. Hence his decision to cut short the honeymoon in May 1887. The European part of the “extended bridal tour” would have to wait and, as it turned out, never came to pass.

Grif’s sudden return was vaguely explained in the Times as having to do with “important interests in the courts”. What was happening was that Tina’s inheritance, along with the entire Briswalter will, had been contested nearly two years earlier by a woman alleging to have been Briswalter’s common law wife. When the woman lost her battle in February 1887, Grif could secure Tina’s property and, eventually, a second large property from the Briswalter estate.

Grif now was ready to join the Boom, but it took him a few more months to get the Briswalter and rancho properties ready. Unfortunately for him, the records would later show that the Boom had peaked in July 1887. Grif had a sense that he was late, entering the Boom on September 25 with a small ad in the Herald headlined: “Best for the Last”. And even then he wasn’t really quite set to go. “Griffith J. Griffith will soon open an office,” the ad read, “and within a few weeks will be ready to subdivide and sell some acre property on the Los Feliz Ranch and dispose of some very choice lots in the Briswalter Property.”

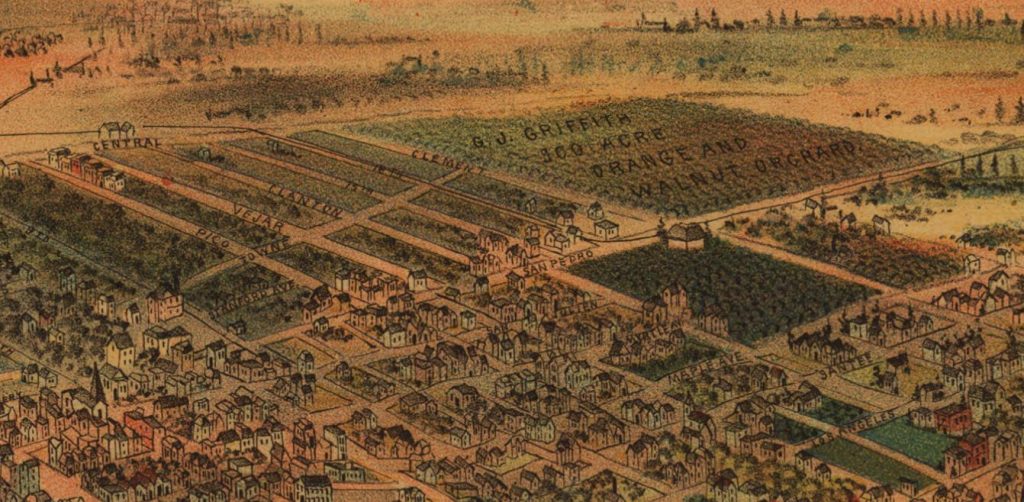

Tina’s two Briswalter tracts were located a mile south of downtown, exactly the direction in which the city was expanding. And while Grif never was able to subdivide it himself, he quickly sold a large portion, 227 acres, to Midwest investors for $969,500 on October 18 — not bad when the entire tract had been valued at $200,000 a year earlier.[5]

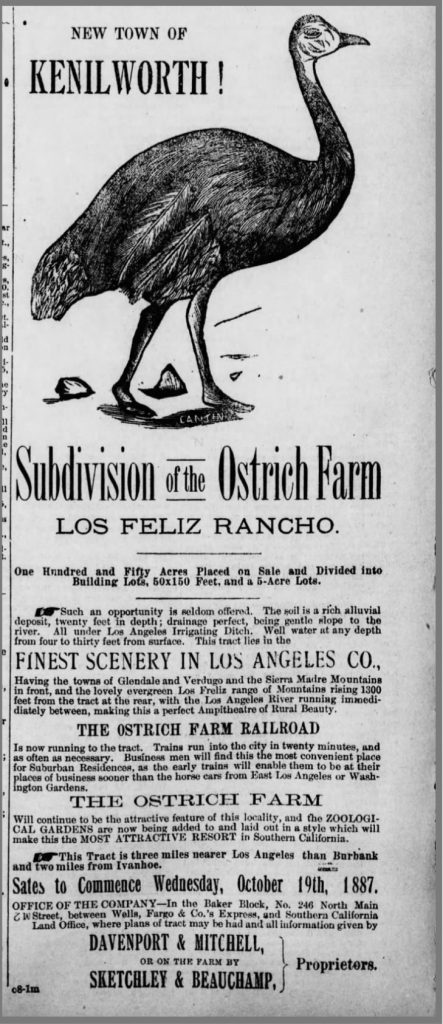

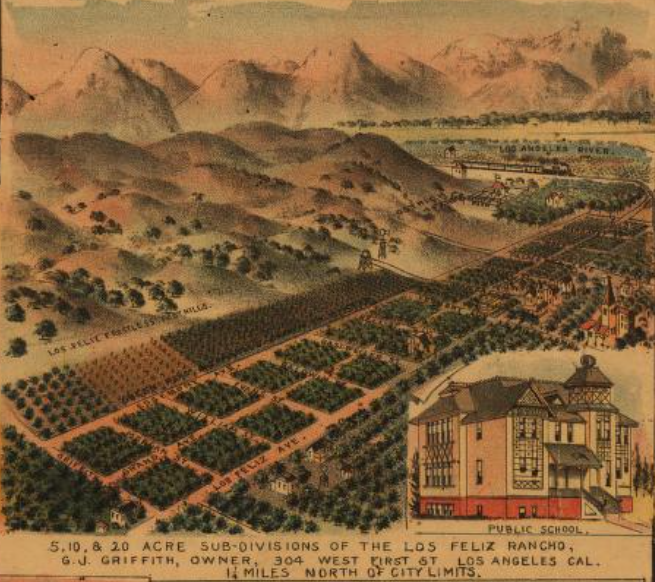

As for the Rancho Los Feliz, surveying and grading lots at the south end took longer than expected and, in the meantime, Grif even saw competition from his ostrich farm partners. They were trying to sell lots on 150 acres, half of the ostrich farm property. Apparently Grif had allowed this arrangement as “Subdivision of the Ostrich Farm” ads (see below) continued for months.

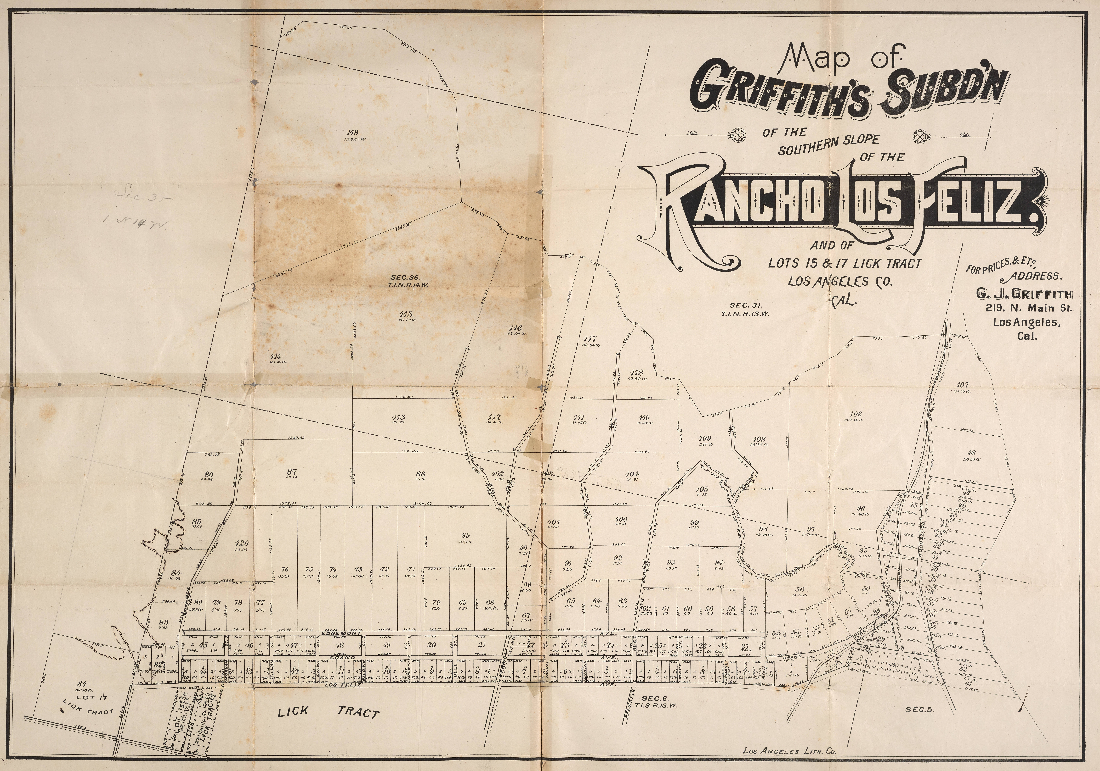

Grif was finally able to make his own move in February 1888, producing a map (see below) showing lots across 1,800 acres of the rancho’s southern slope.

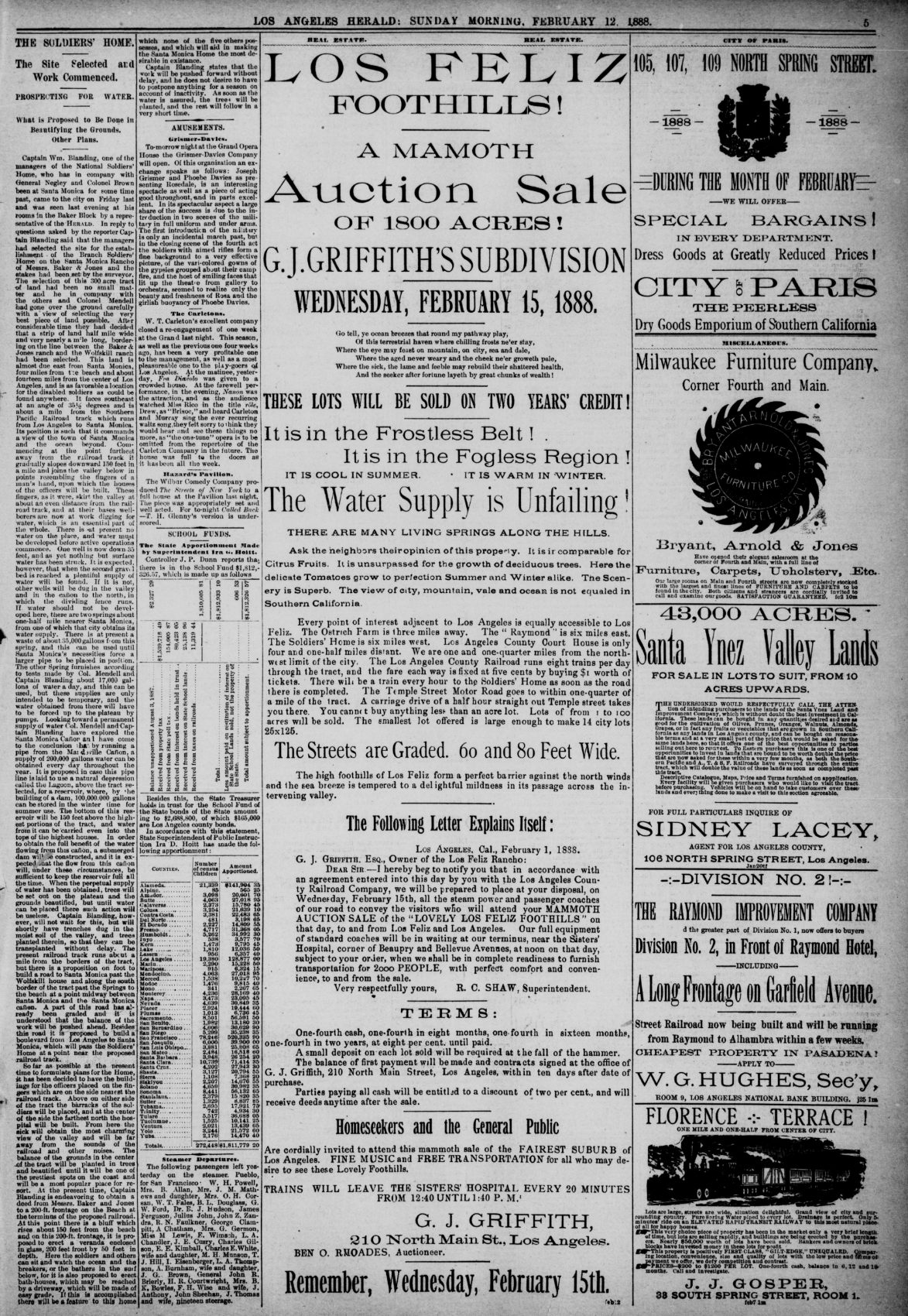

Half-page ads (see below) announced “A Mamoth (sic) Auction Sale” and boasted multiple headlines like “It is in the Frostless Belt!” and “The Water Supply is Unfailing!”. Grif even had a poem written, or perhaps penned it himself:

“Go tell, ye ocean breezes that round my pathway play,

Of this terrestrial haven where chilling frosts ne’er stay,

Where the eye may feast on mountain, on city, sea and dale,

Where the aged never weary and the cheek ne’er groweth pale,

Where the sick, the lame and feeble may rebuild their shattered health,

And the seeker after fortune layeth by great chunks of wealth!”

The Herald touted the planned auction as “the event of the season in real estate circles”, noting free train rides to the site were available for up to 2,000 potential buyers. Other enticements included a free lunch and a live band.

Those 1,800 acres certainly became valuable a decade later, but Grif sold few lots initially as most sales were in other parts of the region and the Boom was slowing down. Even as late as 1903, only 32 homes had been built in the area.[6] Grif also had the disadvantage that Los Feliz was not near an urban rail line, and that’s where all the land speculation was focused. The ostrich farm, with its rickety railway, did not prove convincing enough to entice many buyers. Only in 1904 did the Pacific Electric Railway bring its cars to Los Feliz and even then the area didn’t take off until 1915 and a new property boom — rich movie types from next-door Hollywood.

Desperate to keep public attention on his hundreds of empty lots, Grif in March 1888 embraced an idea by local reporters to create their own affordable community. Grif would sell them one-acre lots at bargain prices so that those working men, and a few women, who earned little but had influence would have homes of their own in what they dubbed the “Press Colony”. Grif took a group of journalists on a “tally-ho” outing, basically a convoy of horse-drawn buggies, to explore the rancho area he had in mind. The strategy produced some very good press for Grif, with journalists saying what a great benefactor to the working man he was, but the potential “colonists” never could get affordable loans and thus their subsidized neighborhood never materialized.[7]

Entire Rancho for Sale

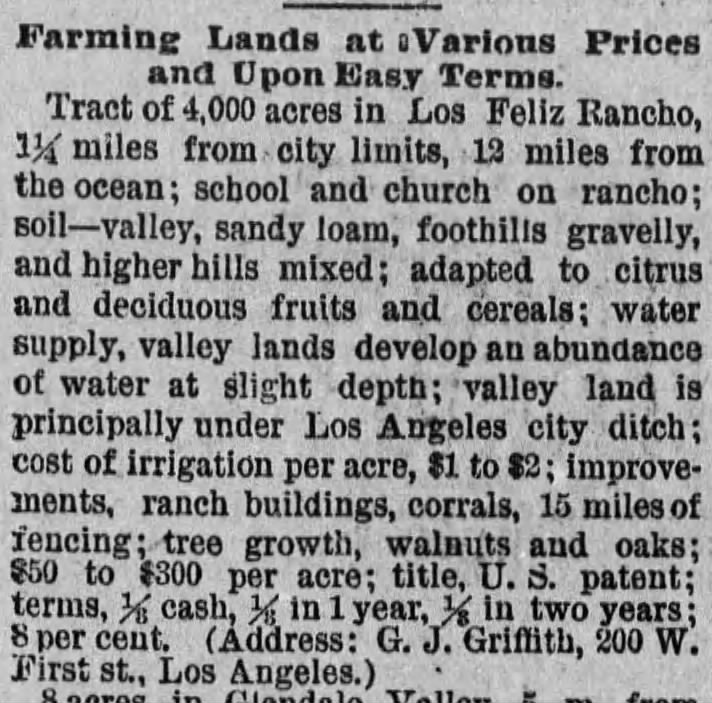

Having failed at subdividing part of Los Feliz, Grif tried other routes to capitalize on his property. In 1889, he even offered to sell ALL 4,000 acres. “Farming Lands at Various Prices and Upon Easy Terms,” read a small ad in the Times on February 26 (see below). It was an uninspired attempt to sell. No colorful “boom” language, just the facts: “tract of 4,000 acres” that included 15 miles of fencing, lots of walnut and oak trees, even a school and church on the property, at prices from $50 to $300 an acre, flat farmland being the most expensive. Loans at 8% up to two years.

That didn’t pan out either – but imagine that, had he sold the rancho there would be no Griffith Park today — and in 1891 Grif shifted the subdivision advertising (see below), focusing on the most developed lots closest to the city. Telegraphing that his rancher days were ending, he also announced a “Great Sale” of livestock and firewood. With Grif now focused more on the city and Tina’s Briswalter properties, little was done on the rancho over the next few years — save for Grif allowing a treasure hunter to look around for “gold, silver and other booty” in exchange for a 25 percent cut.[8] Alas, that too amounted to nothing.

No Bust Post-Boom

As for the Boom itself, it didn’t so much pop as fizzle. Those speculators who lost money or never made their fortune soon left and the city’s population dropped from 80,000 in 1887 to 50,000 in 1890. And yet Los Angeles did not fall into a new economic rut.

“Three rushes” is how one historian described Southern California’s growth spurt, capitalizing on a health rush, land rush and orange rush to attract well-to-do infirm Easterners, speculators/investors and Midwest farmers. The three rushes “were not only bigger than the gold rush,” he wrote, “they concentrated the state’s population in the south.”[9]

Many of those who made money off the Boom built magnificent homes, especially Queen Anne-style mansions with turrets, gables, and wraparound porches. It was the time, Van Dyke wrote, of Los Angeles’ “finest residences and stores, its great street improvements, its perfect system of cable roads.”

Los Angeles, much to the pleasure of boosters like Grif, was also becoming more like the rest of the United States and less like Mexico. The 1888 voter records showed that the vast majority of the 26,000 men registered to vote had been born elsewhere. States like New York, Illinois, Indiana and Ohio; countries like Germany, Britain and Ireland. Protestants were the primary religious group imported into the region and they quickly set about to tame local vices. In 1890, they secured a city committee on public morals and were prominent in cracking down on saloons, gambling and prostitution.

That, in turn, meant the end of a cultural era. The Boom “wiped out forever the last traces of the Spanish-Mexican pastoral economy which had characterized California history since 1769,” wrote Glen Dumke in his classic The Boom of the Eighties in Southern California. “The gold rush made northern California a real part of the United States; the boom of the eighties did precisely that for the south. Where once the ‘cattle of the plain’ had grazed in silence over rich acres, now the American citizen built his trolley lines, founded his banks, and irrigated his orange groves. The boom was the final step in the process of making California truly American.”

Post-boom the “old” routines of farming and trade resumed, and the fact that the area was prospering in 1890 became “the most astonishing fact in its whole history,” Van Dyke wrote.

The prosperity also created the city’s first traffic nightmare — horses and cable cars jousting for space on the main avenues. So much so that one pioneer recorded that in 1888 the city issued its first traffic law: no means of transportation may cross an intersection faster than walking pace.[10]

Grif, for his part, fared well thanks to having sold the large Briswalter tract and then, in 1890, secured another Briswalter property (see map above) in the final will settlement. And he did have a few other things on his mind. A son and heir, Vandel, was born in 1888 and later that year the family traveled to Mexico for a month, perhaps to see his mining interests. Then, in 1889, Grif was sued by an Englishman who had leased some Los Feliz land in hopes of expanding the struggling ostrich farm. That tenant, Frank Burkett, claimed Grif reneged on a deal to let him sell the land he was leasing. After the courts ruled in Grif’s favor, Burkett on October 28, 1891, sought his own justice: He shot Grif in the back as he was waiting in his carriage while Tina visited her mother’s grave.

Grif would have died had Burkett not mistakenly used birdshot instead of buckshot, which uses deadlier pellets. As for Burkett, he thought he had killed Griffith so he immediately took out a handgun and killed himself. The Times tritely presented the news:

Attempted Assassination and Successful Suicide

The Herald was just as tasteless with its secondary headline:

Blows Out His Brains With a Revolver.

A quick recovery allowed Grif and family to travel to Europe and, on his return, Grif resumed his mostly urban activities. He played benefactor as well as protester: donating a strip of Briswalter land to the city so as to help connect a growing Los Angeles[11], while also signing a petition to lower property taxes[12].

- San Bernardino Daily Courier, September 25, 1887. ↵

- Joseph Netz, "The Great Los Angeles Real Estate Boom of 1887", Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California, 1915-1916, pp67-68. ↵

- James Guinn, in 1901's Historical and Biographical Record of Southern California, pp138-143, details the boom years and railway price war. ↵

- Robert Fogelson in The Fragmented Metropolis, pp78-79, notes that the 1880s marked the start of Los Angeles' decades-long boast that it was the fastest growing city in the United States. ↵

- Herald, October 19, 1887. The Briswalter estate had three properties, one of which was left to the estate managers and two to Tina, per the Times of April 24, 1885. ↵

- Donald Seligman, Los Feliz: An Illustrated Early History, pp50-60, details how slow it was for Grif to subdivide the southern part of the rancho. ↵

- Herald, March 19 and 26, and April 9, of 1888 . ↵

- Griffith Family Papers, contract signed on February 20, 1896. ↵

- Glen Gendzel, “Not Just a Golden State: Three Anglo 'Rushes' in the Making of Southern California, 1880-1920.” Southern California Quarterly, Winter 2008-2009, pp349–78. ↵

- Workman, The City that Grew, p235. ↵

- Times, December 17, 1896. ↵

- Grif's name was at the top of the list of noted Angelenos who met to demand lower taxes and non-political appointees at fire and police departments. See J. Gregg Layne, "Taxes and Consolidation of City and County", The Quarterly: Historical Society of Southern California, September-December 1937. pp145-146. ↵