10 The Shooting

SEPTEMBER 3, 1903

________________________

“All this sensational talk about our quarreling is cruel and false. Our married life has been like one long courtship. … She is my ideal of all that a wife should be.”

— Griffith J. Griffith speaking to the Herald the day after the shooting

Grif would often talk in commands, especially to Tina, but on the afternoon of September 3, 1903, his tone was pleasant. He was suggesting a stroll, just the two of them, and Tina was only too happy to agree.

They, along with son Van, had been at the Hotel Arcadia in Santa Monica for about a month – an annual summer tradition. The seaside resort was a welcome break from downtown’s hustle and bustle. But even by Grif’s standards, and given that he was supposed to be vacationing, it had been an exhausting last few weeks. August had started with the Pacific Art Tile grand opening and it remained busy for Grif: helping organize the annual reunion of Civil War veterans; pursuing his tax reform crusade; arbitrating a dispute over what to name a Hollywood street; and dealing with Park Commission issues, including Col. Eddy’s proposed incline rail up to Griffith Peak.[1]

While in Santa Monica, Grif would hop on the train to get to Hollywood or downtown, the latter often for Park Commission work. The city’s parks were back in the news that August, and that meant more prominence and significance for Grif. Central Park, for one, had become a magnet for soapbox diatribes and Grif was tasked with drafting an amendment to bar groups of five or more people from talking on city park property. Grif and the other park commissioners could also start to leverage the Times’ support on August 9 of a proposed bond to raise money for park improvements and “a system of first-class boulevards, uniting all the principal parks.”

As for Griffith Park, and after years of Grif’s efforts to get a 5-cent rail fare as stipulated in the park donation, it now looked like two companies would do just that. One was a rail line from Tropico into the park. The other was the recently approved funicular to take visitors to the top of Griffith Peak.[2]

Other activities that month included Grif and Tina hosting a dinner for friends at the Arcadia on August 16 and, two days later, Grif and a friend took a day trip to Catalina Island where they hunted, and bagged, a few wild goats.[3]

When Grif did find himself at the Arcadia, his typical afternoon was a carriage ride with Tina so as to exercise his two horses. But on September 3, since the family were to head back to Los Angeles the next morning, the idea of a stroll seemed more appropriate. As Tina would later recount, Van was at the beach with the hotel owner’s son, giving Tina and Grif time without the distraction of a 15-year-old in tow.

The hotel was on a bluff overlooking the beach, just south of where the Santa Monica Pier is today. It was a majestic building, the premiere getaway in Southern California due to the ocean breezes and wide beach. The Griffiths had been staying in the presidential suite with its two rooms.

Tina would later tell her sister that Grif had been “unusually pleasant” in the two days leading up to the shooting and that afternoon was no exception. The couple first visited one of the local “bath house plunges” — a large, indoor, heated saltwater pool where dozens could swim and, in some locations even practice trapeze arts. Viewing stands allowed people watchers, like the Griffiths, to be entertained.

The couple then continued their walk, stopping at a curio store inside the hotel’s bath house so that Grif could purchase a post card to send to an uncle.

My, He Looks Peculiar

A short while later, Grif suggested Tina return to their hotel suite to start packing while he made a quick visit to say goodbye to Wiley Wells, an old friend living in Santa Monica.

Tina, once back in her room, opened a large trunk and started packing.

Grif came in a short while later from the adjoining room and started to fold up a coat and trousers.

“Do not mind the little things in the dresser drawers,” Tina said gratefully. “I shall attend to them.”

“Up to this time on that day,” she would later recall, “nothing of an unkind or quarrelsome character had passed between us. Mr. Griffith had been pleasant in all his actions toward me that day.”

But after a few minutes of each packing some things, Grif picked up Tina’s prayer book and walked over to her. Something had changed, he was agitated, no longer the tender Grif.

My, he looks peculiar, Tina told herself just before Grif — now determined, no longer deferential — commanded: “Would you swear on this prayer book the same as you would on a Bible?”

Confused, Tina had to step back and gather her composure while she measured him up.

“Why, certainly,” she said after the initial shock.

“Get down on your knees,” Grif fired back, “and answer these questions.”

Fear overtaking her, Tina saw Grif also had a revolver in his right hand that was tucked behind his back.

“Griffith, put down that revolver. Why do you hold it?”

“You don’t think I would hurt you with it, do you?” he asked.

“Put it down,” she begged, but he did not.

“Close your eyes,” he demanded. Expecting the worst, Tina asked for a few moments to pray and then Grif pulled out a notecard and read from it.[4]

“Did you ever hear or know anything about Briswalter being poisoned?” he asked, referring to the family friend who had left most of his farm property to Tina in 1885.

“Why, no,” Tina responded, her eyes lowered but not completely shut. “I know that he had a sore foot and blood poisoning from that and nothing else.”

“Have you been implicated with or do you know of anyone giving me poison?”

“Why, certainly not,” she said, “you surely know I have not.”

“Have you always been faithful to your marriage vows?”

“As God is my judge,” she said, “I have and you know that I have.”

Still on her knees and eyes lowered, Tina was able to see Grif’s right hand as he suddenly drew the gun from behind his back.

“Why, Papa, what do you mean? Why, Griffith! Griffith!!”

In the next second, Grif fired at her face. Tina fell backward, the bullet having pierced her right eye. Blood streaming down her face, Tina got up, struggled briefly with Grif and then rushed towards a window. It was shut, but she managed to raise it. “I have to escape,” she told herself, even though she saw it meant jumping to a covered portico below.

That account of what happened at the Arcadia on September 3, 1903, was how Tina described the events first to her family, then to authorities. The dialogue that starts while the two were packing is largely from her statement made to the district attorney on September 5 and used that same day to charge Grif with attempted murder. At the preliminary hearing and later trial, she would elaborate on the details, and her recollection of the exact words exchanged with Griffith would vary slightly, but essentially she never deviated from what took place.

Tina concluded the charging statement with a bit of context about Grif’s recent behavior. “For a number of years Mr. Griffith has acted as though he was afraid of being poisoned; he seemed to try to conceal that fear, but I noticed it,” she stated. Even at the hotel where they lived, “I had to order the meal for the family as a whole, for if it came in individual orders he would exchange portions with us. Some time ago he acted peculiarly; one night he stood in the room and said sternly: ‘Come in here; I want to speak to you.’ His look and manner so frightened me that I ran out of the house and away to my sister’s place.”[5]

A 16th of an Inch

The ordeal didn’t stop with the gunshot. “Though bleeding from the bullet wound in her head, and bruised and severely shaken up and stunned by her fall of twelve or fourteen feet from the third-story window, Mrs. Griffith almost immediately after the plunge regained her feet, crawled across the slanting roof of the veranda and reentered the hotel through the open window of a second-story vacant room,” the Times reported in its extensive coverage the next day. “Exhausted by her injuries and hysterical through fright and anguish, she sank upon the bed.”

The thud of Tina landing on a rooftop had alerted hotel staff, and a bell boy following Tina’s cries was the first to find her. “Mrs. Griffith was on her knees, her face and the upper part of her waist being covered with blood,” he told the Herald. “She was crying and sobbing.”

The hotel owner also rushed in, Grif right behind him. “For God’s sake don’t let him in, he has just shot me,” Tina would later testify. “I don’t want him to come in. He must have been crazy.”

A doctor was called in who stopped the bleeding and gave Tina an opiate to ease the pain in her left shoulder, which she had landed on in the fall. It was later found she had fractured the humerus bone just below the ball that fits into the shoulder joint.

Tina feared she was near death, the doctor later told the Herald. “If there is any sudden turn for the worse will you let me know?” she begged him. “I want to make a written statement before I die.”

Santa Monica did not have a hospital at the time and since the last scheduled train to Los Angeles had already left, Tina had to spend the night in the hotel. By early evening, her sister Lucy and her personal physician, Dr. M. L. Moore, were by her side. Grif initially told reporters he had called for her sister, but it was later revealed that Van had actually made the call at Tina’s request.[6]

Moore’s descriptions of his initial exam as well as surgery the next day were as dramatic as they were detailed. “The bullet from the revolver had struck squarely on the sharp edge of the upper rim of bone over the eye,” he told the Herald. “The sharp edge of the bone had split the bullet and a part of it had plowed its way upward under the skin. I administered a local cocaine anaesthetic and removed this part of the bullet. The other and larger portion of the bullet had entered the eye socket. I gave Mrs. Griffith an opiate and then made arrangements for her removal to the California Hospital, which was done Friday morning.”

In surgery, he added, “I made an incision, following the line of the eyebrow. I then turned down the flesh and found that the bone had been splintered and caved in where the bullet struck. I removed several pieces of the bone and found that the dura mater of the brain was exposed, as the bones had been crushed, but no part of the bone had pierced the brain tissue.”

A second surgeon “found that the bullet had crushed the coats of the eye and that the liquid matter had escaped, leaving the ball of the eye flattened out.” That surgeon “removed the eye and I again took the case,” Moore continued. “I found the larger part of the bullet imbedded in the fatty lining of the eye socket. This I removed and then took out several more pieces of splintered bone.”

“If the bullet had struck Mrs. Griffith one-sixteenth of an inch below where it did,” he added, “it would have gone through the eye socket and into the brain.”

The next few days were still touch and go. The Herald listed it clearly: “There still remains danger from inflammation following the removal of the eyeball; danger from internal injuries sustained in the fall to the porch; danger from meningitis following the impact of the bullet on the skull. It is believed that whether Mrs. Griffith will live or die cannot be told for six or seven days to come.”

Wound ‘Amounts to Nothing’

What was Grif doing and saying right after the shooting? He and Van stayed in their hotel suite the night of the shooting, and in the morning the entire entourage accompanied Tina, who was placed on a stretcher and wheeled into the mail car of the first train to Los Angeles.

While Tina was in surgery that Friday morning, Grif ventured to his office and City Hall, where the council a day earlier had signed off on Eddy floating bonds to finance his incline railway, and then to the Jonathan Club for lunch. It didn’t take long for word to get around that Tina had been hurt and, as Grif left the club, he was approached by reporters.

Mrs. Griffith was bruised in a fall and would be fine in a day or two, Grif pronounced, but only a few sentences later he acknowledged a pistol had gone off as well. Still, he insisted the injuries were more from the fall.

“There had been no quarrel between yourself and your wife?” An Express reporter asked.

“Not the slightest,” Grif insisted. “There never has been any trouble between my wife and myself, and we have been married seventeen years. The whole thing, I tell you, was an unfortunate accident, in which luckily no one was seriously injured.”

The reporter probed further. “Then you did not shoot at your wife?”

“Most certainly not. The whole thing was purely accidental.”

Grif elaborated in remarks to the Herald, saying he was packing when he heard the shot. “This thing has completely unnerved me. You know how those accidents, for there can be no question this was an accident, come upon one all unawares, and one never knows how it happened,” he said, as if seeking confirmation from the reporter that he spoke the truth. “It just comes somehow, and you have no warning and no chance to prepare for it.

“This is how my wife was shot,” he continued. “I was bending over my suitcase laying some of my belongings into it, when I was startled by a report and turned to see my wife fall to the floor.” Perhaps the gun had been between some clothes and went off as Tina moved them to her trunk, he surmised. In any case, “She was unconscious … the blood was streaming from her left eyebrow, and I saw I must summon help at once. The wound did not look like a serious one. It seemed as though the bullet had struck a glancing blow. In fact, it amounts to nothing at all.”

Aware that people were starting to talk of marital discord, Grif continued his version. “All this sensational talk about our quarreling is cruel and false. Our married life has been like one long courtship. … She is my ideal of all that a wife should be.”

Grif probably should have kept his mouth shut, or closed it right there, but he went on and on, and then touched a nerve with Tina’s family. Some relatives wanted Grif charged with attempted murder but others, Tina too, initially resisted, citing how scandal would taint her son’s future. Grif’s comments made that argument a hard sell – especially when he mentioned “suicidal mania”. No one who knows us would think “that I would injure my wife, nor that she would think of suicide,” he told the Herald. Just placing the idea of suicide in the minds of the public infuriated Tina’s family.

On top of that, Grif said Tina’s religious fervor could at times make her crazy. “During all our seventeen years of married life we have never had a word of disagreement, save on the subject of religion and that was merely as a matter of belief and implied no personal discord. My wife is a devout Catholic and that is another reason in my mind against the possibility of the suicide theory. My own state of mind is an impartial appreciation of the merits of all religions. The fervor of Mrs. Griffith’s devotion often drove her to the verge of dementia. At those times she was almost irresponsible.”

“The poor thing is a Catholic,” Grif elaborated for the Times, and “believes in that sort of thing, doesn’t know any better. But on this occasion there was no quarrel.” Asked if he had been drinking at the time of the shooting, he replied: “On Thursday I drank nothing to speak of. In fact, I cut down on that sort of thing several weeks ago.” And if it was an accident, the reporter asked, why would Tina flee through the hotel window? “Maybe it was to get some fresh air,” was his awkward reply.

The Mesmers Counter

Mesmer family members gathered just a few hours after the comments were published, trying to decide what to advise Tina, who was still weak in hospital and hadn’t decided whether to press charges. While no decision was made that day, the Express reported that the Mesmer family had let it be known that:

“The married life of Colonel and Mrs. Griffith was not as happy as it had been represented, and that Colonel Griffith was not the model husband that he represented himself to be. That he had been drinking heavily for several months was generally admitted, and when under the influence of liquor, he made his wife’s life almost unbearable. Even when at himself his manner toward her was overbearing, and she was subject to frequent humiliation in public. Mrs. Griffith was a devoted wife, completely under the influence of her husband in all things except her religion, which she would not give up for him.”

“He had determined to bend her to his wishes in this matter, as he had in everything else,” the family elaborated, “and she had refused to obey.”

“If Griffith did the deed, we are inclined to believe that the man is insane. We have thought so before. He is a moral man, but he has his hobbies and ideas and some of the later have at times almost verged on insanity. It is so with his hatred of the Catholics.”[7]

Tina’s sister Lucy went on the record questioning Grif’s sanity. “I have always thought that my sister’s husband was not right mentally,” she told the Herald, “although I did not consider him violent.”

Lucy’s husband elaborated further, suggesting the fight had been over Van’s religious upbringing given Tina’s devout Catholicism and Grif “hating the Catholics worse than poison. The question of the bringing up of their son has always been a source of trouble, and it is thought that this was the cause of the words.”

Some family members even raised the possibility that Grif had planned to stage the shooting as suicide, using Tina’s religious faith against her. Grif probably had Tina get her prayer book to show “a fit of religious dementia” where she was “preparing for death by saying her prayers,” an unnamed relative told the Express.[8]

News Pals Turn on Grif

Tina’s family now having fully turned against Grif, it became easier for some newspapers to also question this “titan of Los Angeles”.[9] What goodwill he had built up with the earlier Press Colony housing project and his own bonafides as a former journalist had severely eroded.

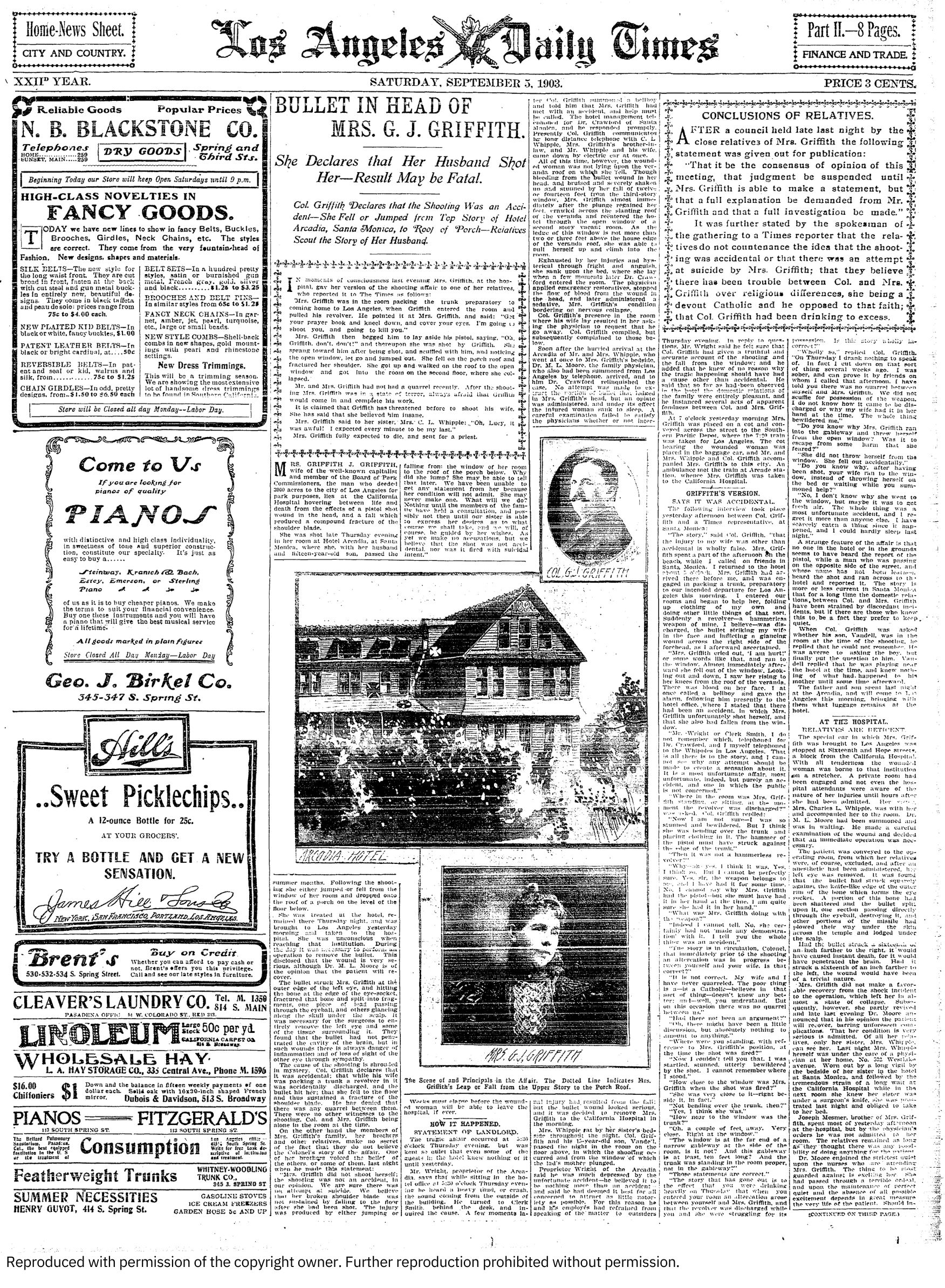

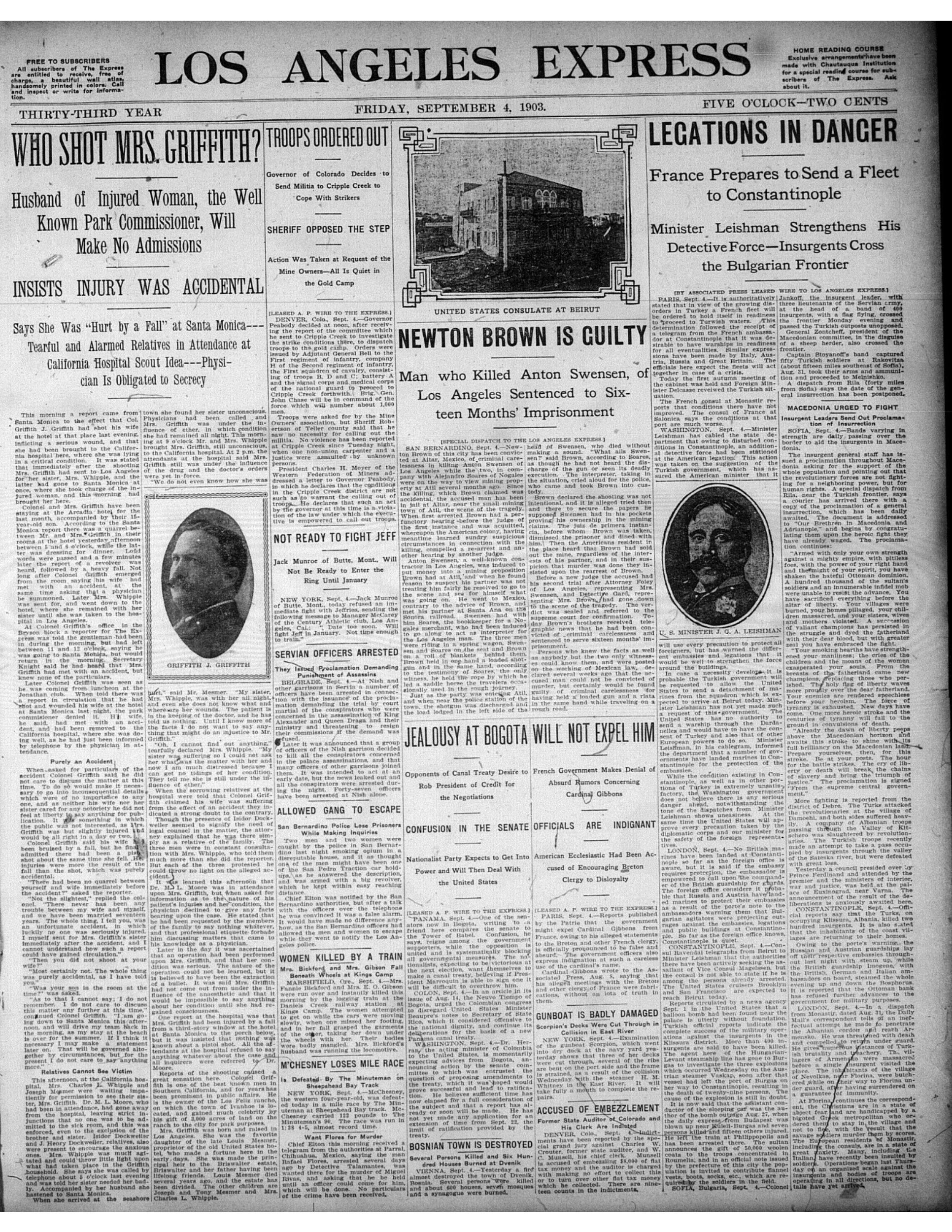

The Express was at the top of that list. The afternoon daily beat its morning rivals in first reporting the shooting, but since details were scarce its first headline was rather diplomatic:

WHO SHOT MRS. GRIFFITH?

The next day, however, the paper’s lead editorial — titled “Let the Guilty Suffer” — was a not very subtle jab at Grif. We don’t want to prejudge, the Express insisted, “but it must be confessed the circumstantial evidence and his own admissions do not warrant the entertainment of that (accident) theory”. It also lamented that the Arcadia owner and staff had suddenly turned silent, “believing their first duty was to protect the possible perpetrator”.

Police should take Mrs. Griffith’s deposition, the Express added, and if she corroborates what her sister relayed to the press then Griffith “has no right to be at large in this community” and should be arrested pending trial.

An Express reporter’s profile of Grif was no less damaging. “He is intensely proud of his achievements and never failed to declare himself a ‘self-made man’ to his friends,” the writer noted. “His profound egotism and eccentricities were considered harmless, and no one suspected he would do any such deed as that charged to him.”

But the same piece went on to suggest he had gone beyond eccentric. “There are many acquaintances of the ‘colonel’ who declare they have long considered him mentally unsound,” added the reporter, whose use of quotation marks around colonel added to the take down.

The reporter then cited an unnamed “well-known businessman” as saying his family were friends with Tina since before she married, and that she’d often complain “of the attentions Griffith forced upon her and asked protection from him. She said Griffith wanted to marry her, but she could not bear his presence. She was sure he was trying to hypnotize her and I know she was much afraid of him. We were much surprised when she finally did marry him.”

And the reporter could not resist sharing a story about Grif’s ego:

“One day he strutted into the bar at the Van Nuys Hotel. The room was crowded with men, most of them his personal acquaintances. Griffith remarked with his broad, bland smile: ‘Say, I have just had the greatest compliment paid me I ever received in my life. I was standing in company with several friends of mine near here a while ago, when I became the subject of such close scrutiny on the part of a gentleman unknown to me that I went over to him and said, ‘Pardon me, my dear sir, but why am I honored thus with your steady gaze?’ To which he replied: ‘I have been looking at you because you are an exact facsimile in figure and feature of General Grant, the greatest of American generals.’ Colonel Griffith thereupon invited those present to step up and have one on him.”

The reporter finished with a flourish: “Colonel Griffith looks as much like General Grant as he does like Lincoln.”

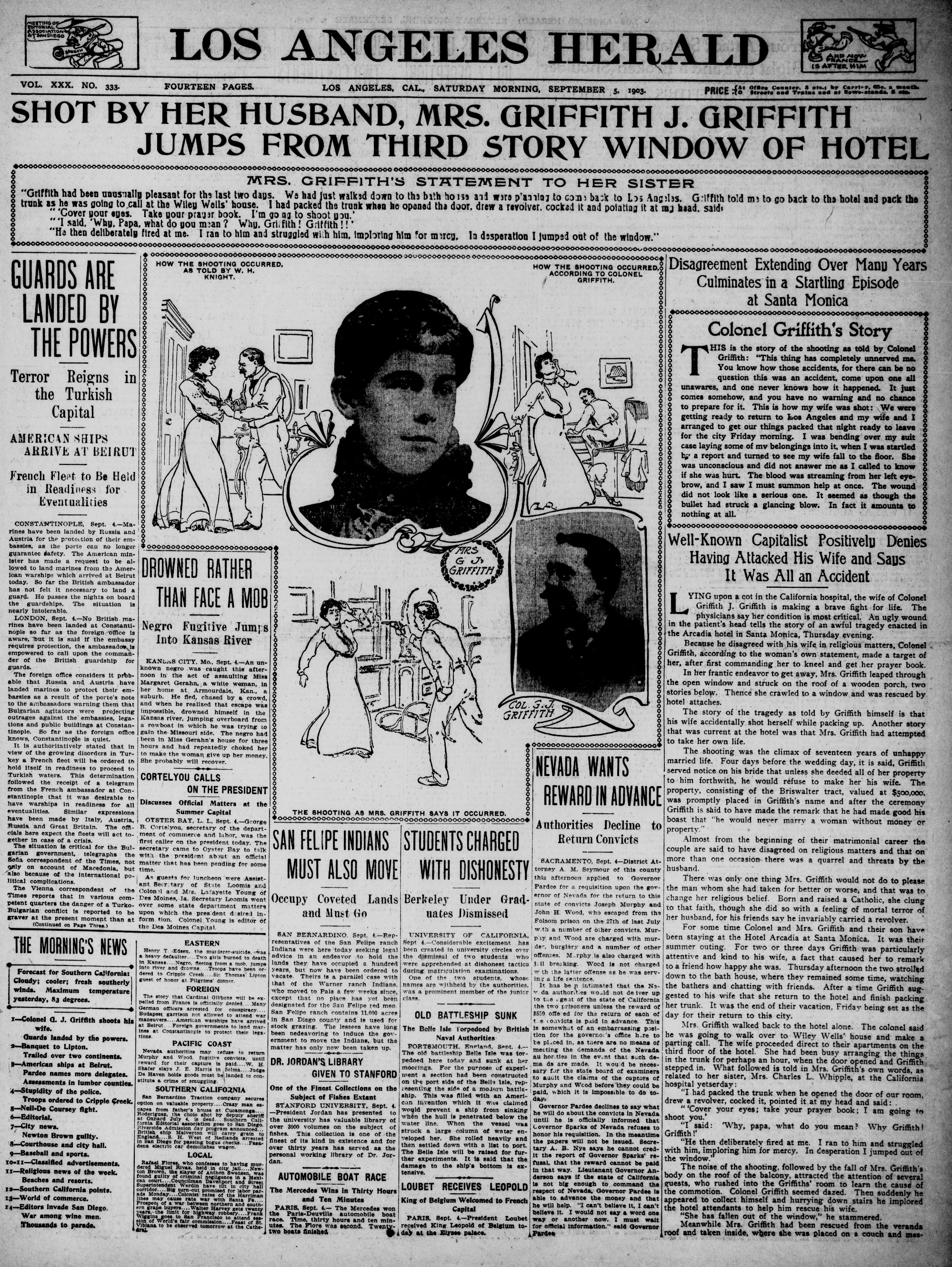

The Herald didn’t waste any time either in condemning Grif. A two-deck headline across the entire front page on September 5 declared:

SHOT BY HER HUSBAND, MRS. GRIFFITH J. GRIFFITH

JUMPS FROM THIRD STORY WINDOW OF HOTEL

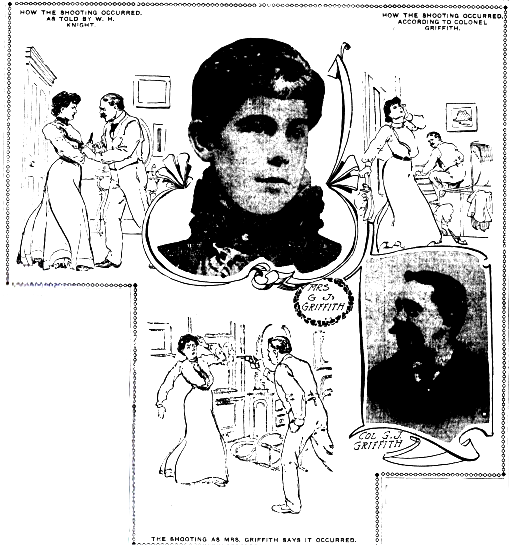

The main story hedged a bit with this smaller headline: “Well-Known Capitalist Positively Denies Having Attacked His Wife and Says It Was All an Accident”. But a headline on Page 2, where the story continued, declared Tina the “Victim of Murderous Attack”. The Herald also ran a large, front-page illustration that confused matters by showing three versions of what happened: Tina’s account via her sister, Grif’s account and a new one — Grif’s secretary said that he had found out through Van that Grif had tried to take the gun away when he saw Tina handling it, and in the struggle it accidentally went off.

At the Times, editors buried the first report in Part II of the newspaper and used an admittedly convoluted headline: “Bullet in Head of Mrs. G. J. Griffith”. Its reporters, on the other hand, were quick to poke holes in Grif’s facade. “It is unfortunately true that Col. Griffith has been drinking lately,” went that first report, adding that he had a reputation of being “peculiar in some respects. When in his normal condition, Col. Griffith has been the personification of geniality, but when in his cups — and he has not frequently been in that condition — he has been known to give way to a display of violent temper when crossed even about little things.”

The next Times report had Grif “drinking freely all afternoon” the day after the shooting and while back in Los Angeles. Without providing names, “intimate acquaintances” from the Jonathan Club and elsewhere were said to know “he was addicted to the habit of drinking absinthe and French vermouth, a concoction rather fatal to sanity if indulged freely enough and long enough.”

While news accounts of the shooting and its aftermath entertained Los Angeles, for Tina it was a time where, after going through so much physical pain, she was about to start months of emotional strain. She pressed charges two days after the shooting, followed three days later by divorce proceedings, and more was to come: a battle over property; the preliminary hearing in November where Tina would first tell her story in court; the actual criminal trial in February where Tina would repeat her story before a jury; and, after all that, seeing her beloved son run away from home after the trial.

- For the Civil War reunion see San Francisco Chronicle, August 17, 1903; for tax reform see Herald, August 21, 1903; for street controversy see Herald, August 19, 1903. ↵

- Herald, August 20, 1903. ↵

- Times, August 16 and 19, 1903. ↵

- Ironically, the notecard turned out to be the backside of an invitation to a recent party where Grif gave a speech on the value of women in society! See Times, April 24, 1903. ↵

- See Herald, September 6, 1903, for full charging statement. ↵

- Herald, September 7, 1903. ↵

- If Grif really was paranoid of Catholics it's possible that he was further unnerved by the election of a new pope, Pius X, a month earlier on August 4, 1903. ↵

- Express, September 7, 1903. ↵

- The Liberator, the city's African-American newspaper, was one of the few to urge calm, editorializing in its September edition that its readers knew all too well what happens when mob rule demands quick trials, convictions and executions. ↵