12 The Trial: Press Self-Destruct

FEBRUARY 16 to MARCH 2, 1904

“We shall endeavor to prove the defendant was suffering from a disease of the brain, and that he was irresponsible for his actions … The defendant developed an insane and fixed delusion that he was being poisoned and that he was about to suffer death unless he took great care and used much circumspection. We will show that in his diseased brain became fixed the suspicion that his wife had been unfaithful to him. He also developed a delusion as to the magnitude of his position, and thought that he was the greatest man in the country … We will prove that his brain was affected by disease, as much a disease as though inflicted with the pustules of smallpox or the rash of scarlet fever.”

— Earl Rogers, Griffith’s lead attorney, in his opening arguments to the jury on February 18, 1904

It had been a long time coming. More than five and a half months after the shooting of Mrs. Griffith Jenkins Griffith, the criminal trial of Col. Griffith Jenkins Griffith was finally getting started. Grif had retained his liberty all this time thanks to the $15,000 bail bond he had posted, but he also had a new enemy in town: the Los Angeles Examiner.

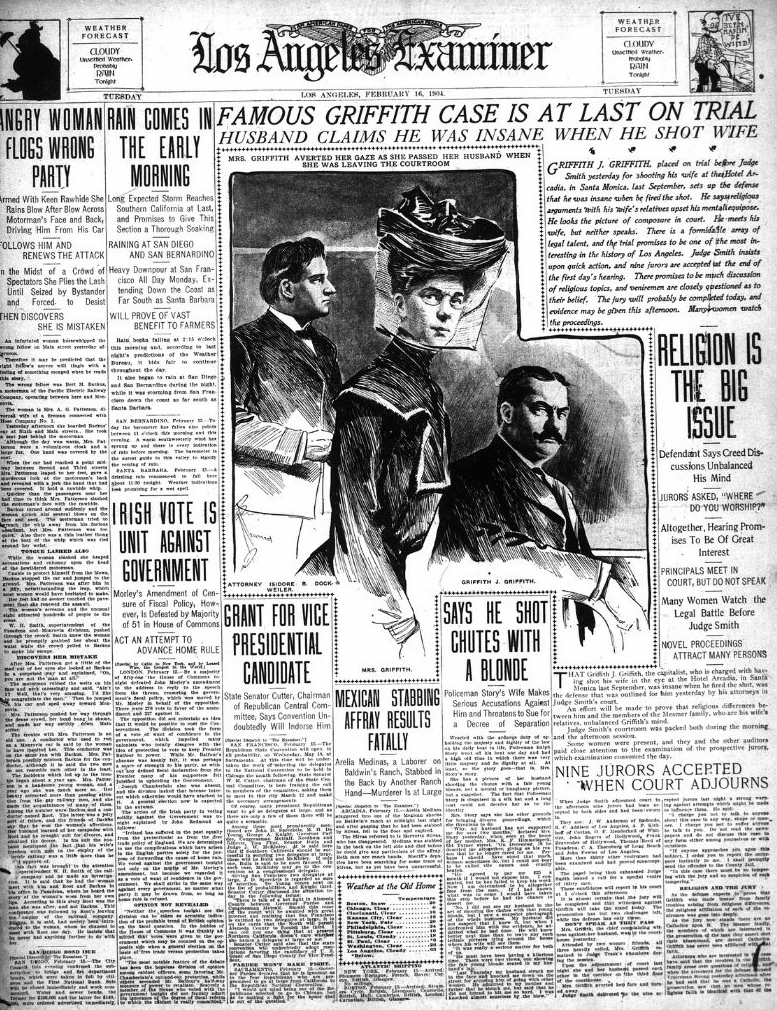

The Griffith trial was the Examiner’s first big story and it would not let go, giving it much more column space than any other newspaper and placing it on the front page more often than any competitor. To set up the trial’s first day on February 16, 1904, it used five of its seven front-page columns to declare:

FAMOUS GRIFFITH CASE IS AT LAST ON TRIAL

Launched just two months earlier by William Randolph Hearst, the media titan who at the time was aiming for the White House, the Examiner broke with the dominant Times and Herald by appealing to the working man and his vote. “An American newspaper for the American people”, declared its masthead.

Grif was a tailor-made punching bag for the Examiner, which never introduced him as “colonel” but as “Griffith, the capitalist” or “Griffith, the millionaire”. On the first day of trial, the Examiner described him not as somber or serious, but as “debonair and partially smiling” when he entered the packed courtroom. Grif was more of a caricature than human. “His jet black hair was curled and combed over his brow,” the Examiner stated. “His little black mustache stood out like a line made with charcoal upon his ruddy face.”

The Examiner also differed from its competitors for its use of colorful, and often loose, headlines as well as large illustrations and occasionally photos from the scene (the only newspaper to do so regularly during the trial). On February 16, for example, a four-column drawing of a stern Tina and a poised Grif (see above) drew the reader immediately to the story.

Jury Duty: Catholics Need Not Apply

Throughout the trial, even during jury selection, the courtroom was packed and women made up much of the audience. “Some are young girls,” the Times would eventually report in a rebuking tone.[1] “Most are elderly women who crane their necks. Many look like women who know better.” The testimony has been so titillating, the Times added, that these women “need have no further fear of sights and sounds that may cause the blush of maidenly modesty.”

Expectations for entertainment were high. “There is a formidable array of legal talent, and the trial promises to be one of the most interesting in the history of Los Angeles,” the Examiner ventured on February 16.

Earl Rogers, Grif’s chief lawyer, kept to his reputation of dressing with confidence, if not cockiness. “Mr. Rogers wore a brand-new frock suit, of the same color as a slate roof,” the Examiner noted on the first day, “sparklingly new patent leathers, and Williams and Walker stockings, with as many colors in them as Joseph’s coat.”

Rogers’ priority during jury selection was to make sure no Catholics served given Grif’s professed hatred, and suspicion, of that faith. Rogers had one other major requirement of a potential juror. “If the defense of insanity should be set,” he asked each, “would you consider evidence in that regard as carefully and regard it as being as good evidence in the case as any other?” Back then, while alcohol was seen as something that could lead men astray, alcoholism wasn’t widely seen as a disease that could drive one insane, and so the idea of treatment over punishment was novel. If Rogers was going to prove that too much drink made Grif temporarily crazy, he needed jurors open to that disease-requires-treatment approach.

It certainly didn’t hurt Grif that juries back then were all-male, and usually all-white. Women were deemed too emotional to be unbiased, or too sensitive to endure criminal proceedings, or too necessary at home to be tasked with jury duty.[2] It took decades of court battles nationwide for women to later secure the right to be on juries, so for now a white male like Grif had the benefit of that old boy’s system.

Once the all-male, all-white, non-Catholic jury was seated, the prosecution started off by calling Tina to the stand. Even if the jurors were all male, they’d have to be touched by her version of events and then shocked when she lifted her veil. In between her emotional retelling and the revelation of her disfigured face, Tina was asked by Gage, her chief lawyer, three questions to portray a violent Grif — one who felt threatened by Tina’s demands for her property and her vow to leave him if he kept drinking:

Had your husband threatened you anywhere before this time? “He came into my room in a strange manner” last May at the Fremont Hotel, she replied. “He kept his revolver under the mattress in the folding bed. He pulled down the bed, took out his revolver, and said to me, ‘I wish to speak with you, step into the next room.’ I tried to get out, but he stood in the doorway and would not let me go. I got out through the parlor door and left home that evening not to return until the next morning.”

He also once at the Nadeau Hotel “took a revolver out of his vest pocket and said, ‘If I ever suspect you of being untrue to me I will use it.’”

Any property differences before you were shot? “Yes, about a month before. I asked him when he would straighten up my affairs and let me have my property … I asked for a settlement, but never got it.”

What if anything had been said to you about leaving Mr. Griffith? “A few hours before I was shot something was said. He had been drinking heavily. I said I would go up home if he stayed there in Santa Monica and continued to drink. About leaving him permanently? Not at the time. I had a conversation about it … sometime in May. I told him if he continued to drink I certainly would leave him.”

Grif’s Questions

Rogers, for his part, had already scored a win when Judge B.N. Smith ruled Tina could not qualify her earlier statement that Grif “must have been crazy” when he shot her. When it came time to cross examine Tina, Rogers did not question any other part of her testimony but instead surprised the court by entering as evidence a menu card from a formal luncheon, the back of which had handwritten notes.[3] Tina acknowledged it looked like Grif’s handwriting and Rogers then began reading the questions Grif had put to Tina so as to emphasize how irrational they were. He included a fourth question, which Grif never got around to reading, where Tina was to vow to “be true to me” and stop haranguing him about the construction of a Griffith family burial plot at the new (and non-Catholic) Hollywood Cemetery.

This evidence of a deranged mind came from Grif himself. Why he didn’t destroy the notes right after the shooting we’ll never know. Instead, they became a key part of his insanity defense. The first two questions would later play into Grif’s suspicion of the Catholic Church poisoning him, the third would be used to argue Grif was paranoid that his wife might be sleeping around, and the fourth showed a man making a mountain out of a cemetery molehill.

Rogers got Tina to confirm that Grif had had these irrational thoughts for four or five years and almost always when he had been drinking. Asked to elaborate on the May incident, she added: “I went back the next morning with my husband’s sister and he promised on the Bible in the presence of his sister that he would stop drinking. I told his sister that whenever he was drinking he accused me of infidelity. He made accusations of my being untrue and of trying to poison him.”

It had been a long day, especially for Tina, so the court adjourned until the next morning, February 17, when Tina was called back for another hour of cross-examination that focused on her use of the word “peculiar” to describe Grif’s behavior to a newspaper soon after the shooting. Tina initially held up well, saying she actually meant “determined” (i.e., not crazy) but, as she got up to leave a courtroom that was packed even tighter than the day before, she collapsed.

“Mrs. Griffith got to her feet, and swayed for a moment unsteadily, as though she would faint,” the Times recounted. “Mr. Dockweiler hurried to her side and escorted her around the end of the table on the way out of the room. As she came opposite her friends, sitting along the rail, she swayed again and closed her eyes. Half a dozen hands caught her and she was half carried, fainting, from the room.”

“Fearing that they might miss some harrowing detail, the crowd gathered in about her with a rush, while the lawyers called for air. A small stampede resulted. They almost ran over her as she hung with limp knees between two lawyers.”

“If there is anything to make a man feel like a pirate it is to have a woman on his hands under such circumstances,” the Times stated, adding that Rogers’ “anxiety and remorse was fairly comical,” especially when he told his team: “Now you don’t suppose anything I asked her made her do that, do you?”

Judge Smith cleared the courtroom, and only allowed back in as many people as seats were available for. “Hundreds waited around the halls for the slender consolation of gazing fixedly at the outside of the swinging doors and knowing that something interesting must be going on within,” the Times reported.

Once order was re-established, the prosecution turned to its first witnesses. Experts stating Grif was sane would come later, for now the goal was to establish a pattern and motive:

- That Grif’s violent temper went back years was testified to by a neighbor who saw “them struggling” inside the Hotel Nadeau in 1900.

- That religion divided them was confirmed by the Hotel Arcadia owner, who said Grif had told him Tina’s Catholicism had been a “thorn in his flesh”.

- That Tina was owed money from her inheritance was established by a real estate agent who said Grif was paid large sums for Briswalter tract sales. Tina’s stepmother noted that, a month after the shooting, Grif told her he and Tina were arguing over Briswalter that afternoon at the Arcadia. “We were both on our knees taking vows” to do better, Jennie Mesmer recalled Grif as saying. “I had a revolver in my hand,” he reportedly added, “but only to intimidate her, and in her struggle to get it it went off.”

A secondary prosecution goal was to show a Grif who kept changing his story of what happened. That was established by a Times reporter who questioned Grif the day after the shooting, getting various descriptions that didn’t match up.

The Griffith family doctor, M.L. Moore, was also called and provided a detailed description of the wound he found. The bullet “struck the superorbital bone of her forehead and split,” he stated, “the larger portion tearing the eyeball and the smaller taking up upward course into her forehead.” Prosecutor Gage added to the drama by introducing as evidence a halved bullet and bone fragments.

Defense strategy: Diseased Brain

The prosecution having rested, it was time for Grif’s legal team to outline their defense. Rogers emphasized that Grif’s brain had become diseased. He didn’t even start with how, just that the disease had overtaken him and he could not control it. “We shall endeavor to prove,” he started on February 18, that “the defendant was suffering from a disease of the brain, and that he was irresponsible for his actions.”

“The defendant developed an insane and fixed delusion that he was being poisoned and that he was about to suffer death unless he took great care and used much circumspection. We will show that in his diseased brain became fixed the suspicion that his wife had been unfaithful to him. He also developed a delusion as to the magnitude of his position, and thought that he was the greatest man in the country.”

“We will prove,” Rogers summed up, “that his brain was affected by disease, as much a disease as though inflicted with the pustules of smallpox or the rash of scarlet fever.”

Only gradually did Rogers introduce the concept that alcohol had caused the disease. It was crucial to convince the jury that Grif had a disease, not that he was an alcoholic. “Poisoning is the chief delusion found in this form of insanity,” Rogers added, and that form “is caused by alcoholism. And so his life went on. The fear of poison, the suspicion of his wife’s infidelity, which he purported to prove by trifling incidents, and other matters preyed upon his mind until it reached the breaking point.”

“A cessation of drinking” the day of September 3, 1903, Rogers argued, caused that “hardened liver, softened brain” to trigger the violent Grif. He only intended to threaten, not kill his wife, and then was shaken out of his trance when the gun accidentally went off. “On the day of the shooting he went to his wife’s room, took a pistol to intimidate her, and read the questions which you have heard,” Rogers continued. “She did the most natural thing, grasped the revolver. In the struggle it went off, Mrs. Griffith was shot, and the defendant woke up.”

Woke up “sane?” interrupted Gage, sarcastically. Rogers glared at him, the defense demanded that comment be stricken from the record, and the judge agreed.

Rogers continued that Grif had been “under treatment since, with good results,” and that the best course would be to let Grif recover at home, not in an asylum, and certainly not in prison.

Defense Expert: Vanity by Insanity

By the end of that long opening salvo, Grif looked like he’d been Rogers’ victim, not client. Life was about to get even lower for the proud, self-made millionaire. The next 10 days would be witness after witness — called by his own legal team — to show that alcohol had turned him into a lunatic. The strategy would start with experts describing why they deemed him insane, then acquaintances describing his huge ego and odd ways, and Rogers’ conclusion: only a madman could draw a gun on his wife.

Dr. Henry Brainerd[4] – a former Los Angeles county hospital superintendent who led the defense team of insanity experts — testified he first met Grif on September 8, five days after the shooting. Grif attributed his heavy drinking to his popularity as a speaker ever since he donated Griffith Park, Brainerd stated. “He made the most egotistical talk I ever heard, and I decided that he was suffering from chronic alcoholic insanity. The expansion of the ego in his case made me think so, for one thing, and his delusion of persecution for another.”

“He said that the Catholics had tried several times to poison him in order that the church might get his property,” Brainerd added, and contended that the late Stephen M. White, a famed Los Angeles lawyer and U.S. senator, was killed by Catholics for challenging the church’s presence in the Philippines.

Dr. Granville McGowan, who had known Grif for 15 years, testified that Grif confessed to drinking a pint of whisky daily for years. Grif also told him that he was sure Tina used hand signals in hotel dining rooms and hallways to attract the attention of other men.

Dr. James Crawford, the first physician to examine Tina after the shooting, related that the first words out of Tina’s mouth to him were: “The colonel is crazy, he is surely crazy.” Fearing she was on her death bed, she asked to make a written statement but Crawford assured her she would survive and thus talked her out of it.

Grif’s acquaintances included one Frederick Purssord, operator of a downtown bathhouse, which back then also meant a place to sleep off the booze. “I thought he was a dipsomaniac,” he said of Grif. “He used to talk to me a lot about himself, about what a great public speaker he was, how he was the richest man in Los Angeles and how he used to come to my place, once at half-past seven in the morning, to get away from his people and friends.”

Jacob Leiser, a self-described “tonsorial artist”, said he had shaved Grif almost daily at the Palace Barber Shop over the last five years. “He used to worry about little things like his wife trying to poison him and things like that. He used to roast the Catholics something fearful and he thought he was poisoned by them several times.” Grif’s banter was so persistent, he added, that his other patrons “would ask me who my ‘nutty’ friend was.”

A Jonathan Club bartender contributed to the pathetic portrait of an egotistical, paranoid drunk, stating that he would typically serve Grif five times a day, starting at 9:30 a.m. Mr. Griffith once even “asked me if I had poisoned him,” Joseph Seaman testified.

Harder yet for Grif to stomach must have been how presumed friends from the elite Jonathan Club described laughing behind his back. “He had lots of vanity,” J.B. Nevill testified, and “bored us with bad stories.” So “we ‘joshed’ him, as we say at the club. Everybody was on the josh except himself.”

Another Jonathan recalled an “experiment to find out whether Griffith was merely egotistical or insane” by buttering him up with comparisons to Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln and Grant in terms of public service. Grif had accepted the flattery, adding that he was overwhelmed with honors, and was even encouraged to run for mayor, but declined so as not to look like he had used his park donation for political purposes.

Other social equals quick to pick on Grif included a park commissioner and two politicians, the latter emphasizing that Grif had an outsized view of how significant he was in the local Republican Party.

The defense lawyers would often set the tone by first asking about Grif’s particular strut. “Was it not a pompous walk as if he was the most important man in town?” Rogers asked one acquaintance. The answer always came across as a yes.

Of note is that neither Grif nor any of his relatives were called by the defense. It appeared that at one time Grif might testify, but doing so would have opened him up to cross-examination by the prosecution. As for relatives, it might have been hard to get them to state that their own kin, especially one who provided financial support, was crazy.

‘A Man Crushed’

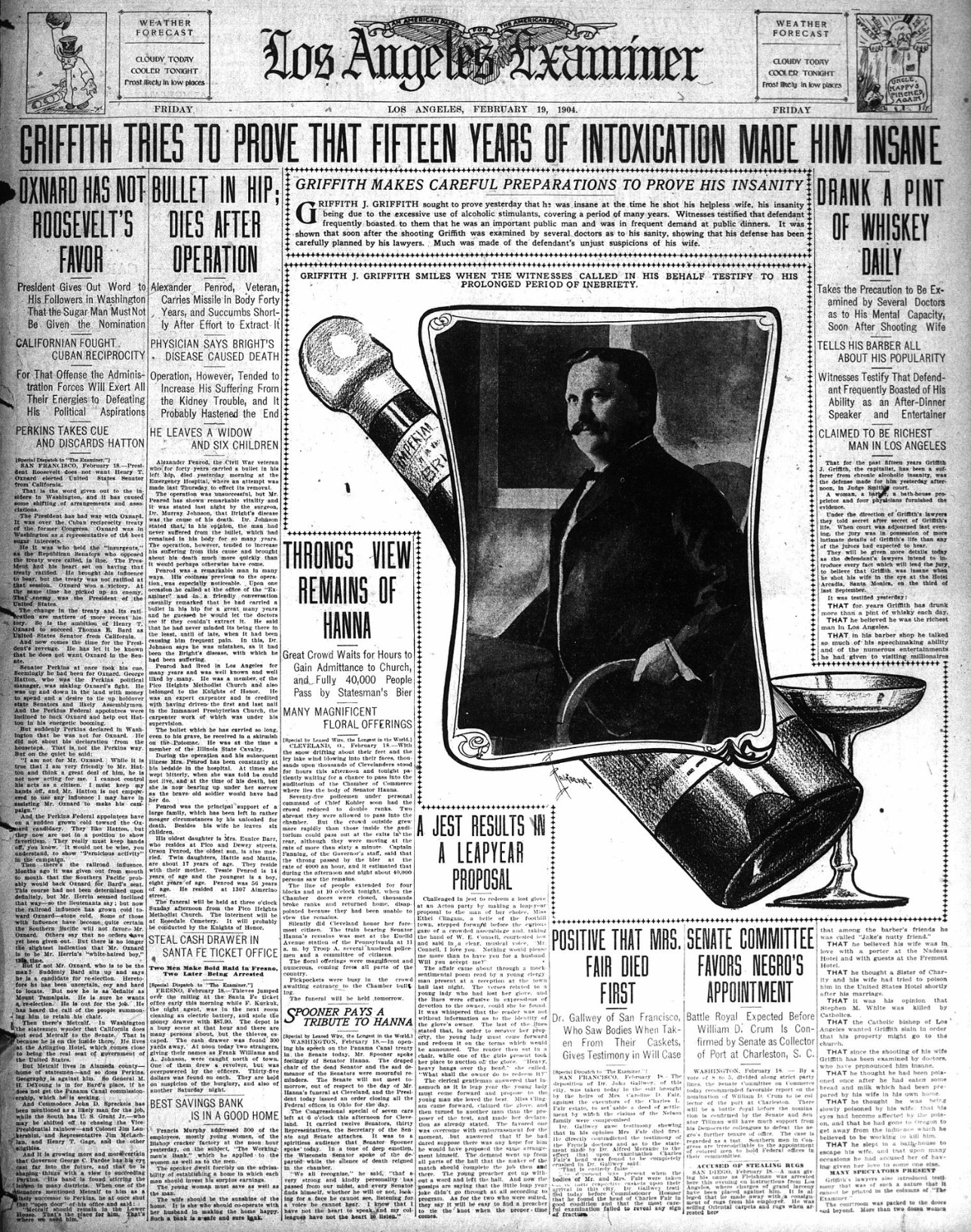

The testimony arranged by Grif’s defense team provided a field day for the press. “Griffith J. Griffith, the capitalist,” the Examiner began on February 19, saw his own lawyers argue:

“THAT for years Griffith has drunk more than a pint of whisky each day.

“THAT he believed he was the richest man in Los Angeles.

“THAT in his barber shop he talked so much of his speechmaking ability and of the numerous entertainments he had given to visiting millionaires that among the barber’s friends he was called ‘Jake’s nutty friend’.

“THAT he believed his wife was in love with a porter at the Nadeau Hotel and with guests at the Fremont Hotel.

“THAT he thought a Sister of Charity and his wife had tried to poison him in the United States Hotel shortly after his marriage.

“THAT it was his opinion that Stephen M. White was killed by Catholics.

“THAT (he thought) the Catholic bishop of Los Angeles wanted Griffith slain in order that his property might go to the church.”

After a few more “thats” it wrapped up with:

“THAT he thought he was being slowly poisoned by his wife; that his eyes had become affected by the poison.”

“THAT he slept in a bath-house to escape his wife, and that upon many occasions he had accused her of having given her love to some one else.”

The Times, for its part, also “boiled down… the anecdotes of Col. Griffith J. Griffith’s astounding conceit” in its report titled “Great Come-Down for Col. Griffith”. In a tone nearly gleeful, its first paragraph stressed how the defense strategy was taking a heavy toll on Grif: “A crushed, humiliated, pitiable man who sat in court yesterday, cringing under the extremely candid remarks of his own lawyers, was the once haughty Col. G.J. Griffith.” And it got worse:

“Imagine a man who has had the position Griffith has held in this city, sitting a public target for all eyes, while his barber and his Turkish-bath man ventilate their valuable opinions as to whether he was really crazy or merely a drunken rounder.

“He sat there while his own lawyers explained to the jury that he thought himself the greatest man in the world and had been so swelled up and pompous that it went beyond the point of insanity.

“He sat there while two insanity experts explained that his talk about his own importance was the craziest they had ever heard.

“He ‘took it hard,’ as the saying is. His worst enemy would have felt sorry for him.

“He sat at the end of the attorneys’ table, humbly out of the way, his face contorted with shame, and his lips twitching – a picture of utter woe and dejection – a man crushed. He seldom looked up and often would pass his hand over his head, as though he were tired – so tired.”

Prosecution: Vain but Sane

Surely the jury by now was buying the insanity case, it seemed. But Gage and other prosecution lawyers would over the next two days call 22 experts, acquaintances and friends to swear that Grif never lost the ability to distinguish right from wrong — and never took precautions against poisoning as far as they saw.

The only things both sets of witnesses agreed on was that Grif was pompous and a prolific drinker. In the weeks before the shooting, Grif frequented a saloon next to Santa Monica’s Hotel Arcadia and never worried about being poisoned, a bartender for the prosecution testified. He’d visit two or three times each morning, a couple of times in the afternoon and again at night. Usually whisky, but sometimes champagne.

A second Santa Monica bartender called by Tina’s team said Grif kept coming back for drinks even after the bartender had told him he was Catholic.

An Arcadia bellhop noted that Grif enjoyed “Martini and Manhattan cocktails. Of course, we couldn’t serve them openly, so his were brought to him in the office of the hotel. He drank them there, and I never heard that he thought any of them was poisoned”.

The Examiner made hay of Grif’s routine, headlining its February 24 report with:

GRIFFITH’S TOURS ON THE MARTINI

AND MANHATTAN KITE-SHAPED TRACK

The kite referred to the popular tourist rail route through the region and champagne was also on that track, a point colorfully related by the Examiner in describing a Santa Monica policeman’s testimony that he and Grif had sipped together. “Griffith had bought the imprisoned laughter of the peasant girls of France” and that the “guardian” of the peace “had stood up to it like a man had gone away with his share.”

Contrary to the defense’s claim, even the day of the shooting Grif was drinking, four witnesses testified. He bought a bottle of champagne in the a.m., said a bartender, and returned in the afternoon to finish it off. Three Arcadia bellhops who happened to be at the bar added that Grif invited them to whisky since it was his last day at the hotel.

As for poisoning and Catholics, prosecution experts testified that the fear of the former could stem from stomach troubles due to too much whisky, and the latter was a “sane delusion” since Catholicism was mistrusted by many faiths.

Several leading citizens concurred that while Grif could be pompous, they had never seen him act irrationally.

“I’ve drunk whisky with him and have never seen him take any precautions,” declared William Mulholland, head of the city’s water department who a decade later would become a household name for building a 233-mile aqueduct to a parched city. An acquaintance since 1884, Mulholland also tried to reprieve Grif from the constant attacks on his character. “I think Griffith was more pompous twenty years ago than he is today,” he ventured.

By the last witness, the trial had gone through 11 doctors for the prosecution; nine for the defense. “These experts unlocked all the Griffith closets and danced all the Griffith family skeletons in the public eye,” the Examiner delighted. Laymen were 17 for the prosecution, 12 the defense. An Examiner headline summed up the melting pot: “Bartenders and Barbers Give Their Wise Conclusions as Owlishly as the Best Medical Authorities in Los Angeles”.

Closing Arguments: Round 1

The witness phase over, the jury would next hear closing arguments or, as the Examiner put it, “the floodgates of oratory will be opened”. It was February 29, 13 days into the trial, and drew the biggest crowd so far. The courtroom was so packed that the judge opened the upstairs gallery to women only. “A millinery show,” was how the Times described it, “tootsies poking through an iron grating” as even the gallery filled up.

The trial was nearing its climax and the audience, save for one, was soaking up the suspense. “The only person who cannot fairly be said to have been enjoying himself,” the Times wrote, “was a portly man with slick black hair, who sat with his face propped in his hand, his eyes closed – a picture of gloom and despair. Griffith was his name.”

DA Fredericks started for the prosecution, focusing on motive in his three-hour summation. Why attempt to kill his wife? “Realizing that the time was coming when she would leave him and he would have to make a (property) settlement, he decided upon this method of getting rid of her,” Fredericks declared. “Griffith had no love for his wife. He cared only for her property.”

Grif’s first explanation of the shooting, Fredericks reminded the jurors, was when he told a bellboy that Tina had shot herself. “Suppose she had died, what would have been the story?” Fredericks asked. “Griffith J. Griffith, the prominent, wealthy man, would have said, ‘My wife has committed suicide,’ and he would have been believed. It was well planned, but it did not succeed. Why did he not shoot the second time? Because that would have destroyed the theory of suicide. So he had her kneel down, he held the pistol within a foot of her forehead, he pointed it at her eye; he was a dead shot, but by a miracle she was saved. His statement of suicide was upset so he grasps at a chance remark of his victim, who exclaimed as she lay in agony of pain, ‘My God! He must have been crazy’ and endeavors to escape on an insanity plea.”

Fredericks added that the defense experts were conned by Griffith. Doctors and friends who have known Griffith longer than the defense experts, Fredericks said, testified they felt he knew right from wrong, and besides fear of Catholics does not equal crazy. Moreover, Griffith didn’t stop drinking the day of the shooting, undermining the defense argument that “a cessation” caused Grif to snap.

The defense’s rebuttal focused on the alleged motive. The prosecution, attorney James McKinley said in his closing arguments that same day, “would have you believe that this man, who had independent means of his own, who gave that immense tract of land to the city to gain popularity, would throw away that popularity.”

Sorcerer vs. Preacher: Round 2

A second line of attack was left for the next day, March 1, and to the biggest legal guns: the youthful Rogers against the veteran Gage. The courtroom was packed in tighter. “They even stood on agonizing tip toe, peeking over the curtains by the clerk’s desk,” noted the Times, “and more than half the crowd was women.”

Up first, Rogers began by arguing that the “ultimate truth” in the trial was Tina’s own testimony — repeated several times, including when she thought she was dying — that Grif “must be crazy”. Tina also did not mention a property dispute when she provided her account to the district attorney, Rogers reminded jurors, and instead only cited Grif’s fear of being poisoned.

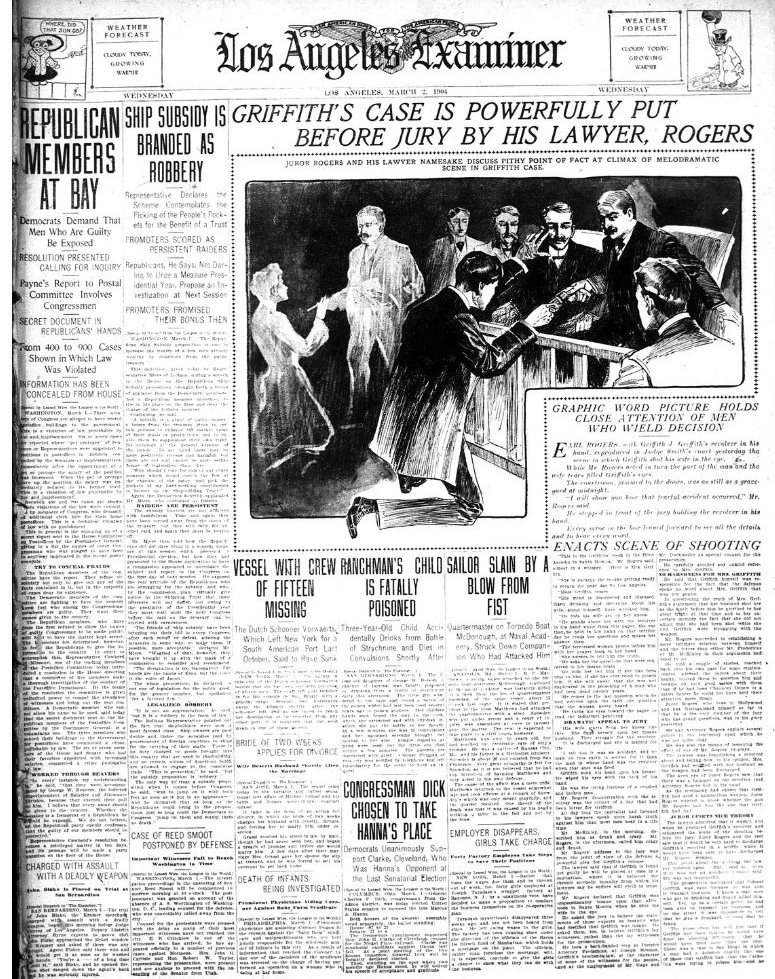

The Examiner noted that throughout his two hours Rogers created an “intimate relation” with jurors by telling personal stories and encouraging the jurors to ask questions.

Rogers steered toward his climax — a re-enactment of the shooting, with Rogers playing both Grif and Tina, while waving a gun and Grif’s menu card with its handwritten questions for Tina. “Tears filled Griffith’s eyes,” the Examiner reported the next day in extra large type. “The courtroom, jammed to the doors, was as still as a graveyard at midnight.”

The full Examiner story went into more detail. Grif had only wanted to intimidate his wife, Rogers affirmed, but that posturing with his gun turned into an accidental shooting. “What would any rational person have done?” he asked the jury, referring to Tina being confronted. “As he turned his eyes for a fraction of a moment to read the fourth question from the paper, and it was hard to read, written in a cramped hand, she took advantage of the situation, grabbed the revolver, and in the struggle it went off.”

“His wife starts from her knees like this,” he said, raising himself. “She flung herself on her insane husband. They struggle for the revolver. It is discharged and she is marred for life.”

At that moment, the Examiner reported, Griffith “was the living likeness of a crushed and broken man … the big tears trickling from his trembling fingers.”

“All day long, the capitalist had listened to his lawyers speak more harsh truth against him than most men hear in a lifetime,” the working man’s paper continued. “Mr. McKinley, in the morning, described him as drunk and crazy. Mr. Rogers, in the afternoon, called him crazy and drunk.”

Just in case the jury wasn’t buying the accident, Rogers went back to the insanity argument. “But even if it was not an accident,” he continued, “Colonel Griffith was not responsible” due to what the defense experts had testified as his condition of chronic alcoholic insanity.

On one of his anecdotal detours, Rogers hinted at his own personal demons with alcohol. “I know something about that myself,” Rogers related. “I know how hard it is for a man to let the stuff alone … if he commits a crime while under the sway of the drink, society, which gives him so many chances to satisfy his unfortunate thirst, must share the blame of the act.”

It wasn’t a perfect performance, however. One of the jurors, taking Rogers up on his offer to ask away, inquired if the gun he had pulled from his pocket was Grif’s. Caught red-handed, Rogers had to acknowledge it was not — in fact, while similar it was much easier to discharge accidentally than Grif’s hammerless revolver, a model designed to prevent just that.

In any case, Rogers’ flair certainly had cast a spell on his audience, but he came across more sorcerer than showman since he was having to defend an unlikable client. Gage, on the other hand, had an appreciative audience when he arrived the next day, March 2, to close for the prosecution.

Locals crammed in again. “The crowd was so tightly wedged in that no member of it could have been extracted with a corkscrew,” the Examiner noted. “The courtroom was suffocating during the last scenes of the trial,” the Times reported, “the sickening heat of close-packed human beings and the deadly used-up air so thick and foul with human breath that it could be carried out in chunks.”

The Herald went into even more detail. “If the situation in the court room on previous days was described as crowded, that of yesterday was indescribable,” its reporter stated. “A small space in front of the jury box, where the attorneys addressing the jury stood, was the only spot in the court room which was not filled with a perspiring mass of humanity.

“Women crowded the galleries, found seats within the railing of the bar reserved for lawyers, and broke all local records for attendance at a trial. Around a hundred people who did not mean to lose the seats they had fought for, brought their lunch with them and remained in the court room during the two-hour intermission at noon.”

And entertained the crowd was, some in the gallery above even snacking on candy, others laughing when Gage took colorful pokes at the defense lawyers. Gage wore his “justly celebrated long boots,” the Examiner noted, while “a white flowing tie had replaced his black one.” The look was folksy — “more like a preacher or a careless member of some backwoods bar,” the Examiner stated, providing readers with a full-page, front-page photo of Gage to prove it.

Gage didn’t role play as husband and wife, as Rogers had done, but was dramatic nonetheless. Looking every bit the Baptist preacher, he held his trembling hands over his head and pronounced: “He led her there in that hotel, to the brink of eternity, and while she prayed with clasped hands to God to save her from his murderous fury, he shot her.”

Accident? Not possible, Gage insisted, as he presented Grif’s hammerless revolver to the jury so that they could try to trigger it while he pulled — in effect replicating how Tina would have been unable to accidentally fire the gun if she had struggled for it. None of the several jurors who tried could get it to discharge given its safety mechanism. Besides, he added, Tina jumped from a window — would she have done that if it had been just an accident?

Throughout his summation, Gage walked back and forth in front the jury box, keeping his left hand in his trouser pocket, the Record related, until, “in his greater flights”, that hand “leaped to action” to emphasize something.

He also let the jurors examine Grif’s menu card, pointing out how parts had been corrected — a sign, Gage insisted, that Grif was not a madman acting irrationally but a conniving husband who took time to plot a murder. He intended to plant the card next to her dead body, Gage stated, to make it look like Tina, “bowed down with shame” after reading the accusations, “had raised her own wild hands and sent her spirit back to the God who gave it.”

And why kill a loving wife? Because Tina kept asking him for control of her inherited property, Gage reminded jurors. Without that fortune, Grif was hardly wealthy and his precious Rancho Los Feliz had been draining his own finances before he donated most of it, according to a former assistant to Griffith. That aide testified, Gage noted, that Grif “could not make enough money out of it to pay the taxes”. The implication: On his own, Grif was land rich but cash poor.

At the height of his three-hour sermon, Gage derided the defense argument that Grif’s insanity only really surfaced at the time of the shooting. “They want you to believe that before the shooting Griffith was sane, that just after the shooting he was sane, but that when he fired that shot he was insane. It is a case of now you see the insanity, and now you don’t, and it is a mighty poor defense.”

The gallery erupted in laughter, Judge Smith rapping his desk to restore order.

Gage’s last appeal was aimed directly at the jury: it was their chance to right wrongs. “Of the 2,000 prisoners in our state there is not one wealthy man,” he noted. A well-known journalist covering the trial later recalled how with that one statement he saw “the jury bristle and fairly itch to make Griffith the first one.”[5]

Gage followed with a concluding remark: “No verdict except a verdict of guilty will satisfy the ends of justice or your own consciences.”

And with that, along with applause from some women in the gallery, the trial was over. It was now time for the 12 white, male, non-Catholic jurors to make up their minds.

SELECT TRIAL HEADLINES IN LOS ANGELES EXAMINER

(on front page unless otherwise noted)

Feb 16:

FAMOUS GRIFFITH CASE IS AT LAST ON TRIAL

Feb 17:

MRS. GRIFFITH SWEARS HUSBAND SHOT HER;

THE DEFENSE TRIES TO PROVE HIS INSANITY

Feb 18:

TOO MUCH RELIGION AND CHAMPAGNE GRIFFITH’S DEFENSE;

MRS. GRIFFITH FAINTS AT CONCLUSION OF HER TESTIMONY

Feb 19:

GRIFFITH TRIES TO PROVE THAT 15 YEARS OF INTOXICATION MADE HIM INSANE

Feb 20:

EXPERTS TELL WHY THEY THINK GRIFFITH WAS INSANE

FAMILY SKELETONS DANCE FOR THE PUBLIC’S DELIGHT

Feb 21:

EXPERTS SAY THAT GRIFFITH J. GRIFFITH’S AFFLICTION IS “ALCOHOLIC INSANITY”

Feb 22:

GRIFFITH’S IS MOST COSTLY OF TRIALS (Page 10)

Feb 24:

GRIFFITH’S TOURS ON THE MARTINI

AND MANHATTAN KITE-SHAPED TRACK (Page 2)

Feb 26:

GRIFFITH LAUDED BY PROSECUTORS; BITTERLY ATTACKED BY DEFENDERS

- Times, February 27, 1904. ↵

- See Wikipedia entry on women and U.S. juries for a detailed history. ↵

- This was the card for the luncheon at which Grif was a speaker on the value of women. ↵

- For a profile of Brianerd, a local pioneer in the field of psychology, see this blog post by the Homestead Museum. ↵

- Harry Carr, Los Angeles City of Dreams, p45. ↵