7 From Panic to Party, then Progress

1893 to 1895

__________________

“With the immodest ambition of surpassing San Francisco in a generation, they kept Los Angeles on a war footing — fully mobilized for self-promotion and improvement.”

— Historian Mike Davis on the boosters whose confidence grew so much they challenged the powerful Southern Pacific railway

Los Angeles did finally see an economic setback, not of its own making but a national recession. The Panic of 1893 hit everyone — the entire United States of America struggled as banks failed and many depositors lost savings. It also marked the transition from Gilded Age to Progressive Era — many felt it was time to check capitalism and the cronyism that its money could buy. A young New York Republican by the name of Theodore Roosevelt would become the Progressive hero the nation was waiting for.

Grif fit right in with the Progressive spirit and started getting involved in activities that were more about civic mindedness than personal profit. One was helping launch the Southern California Fruit Exchange, a farmers’ co-op that later became the famous Sunkist brand.[1] The co-op was all about cutting out, or at least minimizing, the middlemen brokers who “fattened at the expense of the struggling producer,” as Grif would denounce in a letter to the Herald on January 22, 1895. The brokers aimed to buy fruit and produce at low prices in order to make more money for themselves, Grif and his farm peers argued. By the time Grif wrote the letter, the co-op handled most of the region’s oranges.

A second civic enterprise was helping found the Citizen’s League, which aimed to reform city government. Yes, it sought lower taxes by doing away with what Grif and others saw as redundant county services and some founders sought to use it to curb labor unions, but it was also about taking money and power away from political bosses who controlled elections and policy.[2] The league was a bit ahead of its time, and thus didn’t get much traction, but it was the start of Grif’s long-term interest in Progressive politics. Moreover, its goals eventually were championed by the Chamber of Commerce and its more successful League for Better City Government.[3]

Given the recession, marketing Los Angeles became even more of a priority for the local elite, regardless of political affiliation. Two events in particular helped pull the city up by its bootstraps — and both involved looking beyond the city’s borders.

Land of Sunshine — in Chicago

The first was the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Over the previous decade, Los Angeles’ boosters focused on a marketing campaign that piggybacked on winter shipments of oranges, lemons, walnuts and other exotic products to the Midwest and East Coast — in effect selling a warmer, happier life in Southern California. That helped fuel the 1880s Boom, but by the end of that decade more people were leaving than coming and the chambers of commerce throughout Southern California — from San Diego to Santa Barbara — upped their marketing game by sharing a huge pavilion with Northern California at what became the biggest display case of all: a world’s fair in Chicago that attracted nearly 20 million visitors.

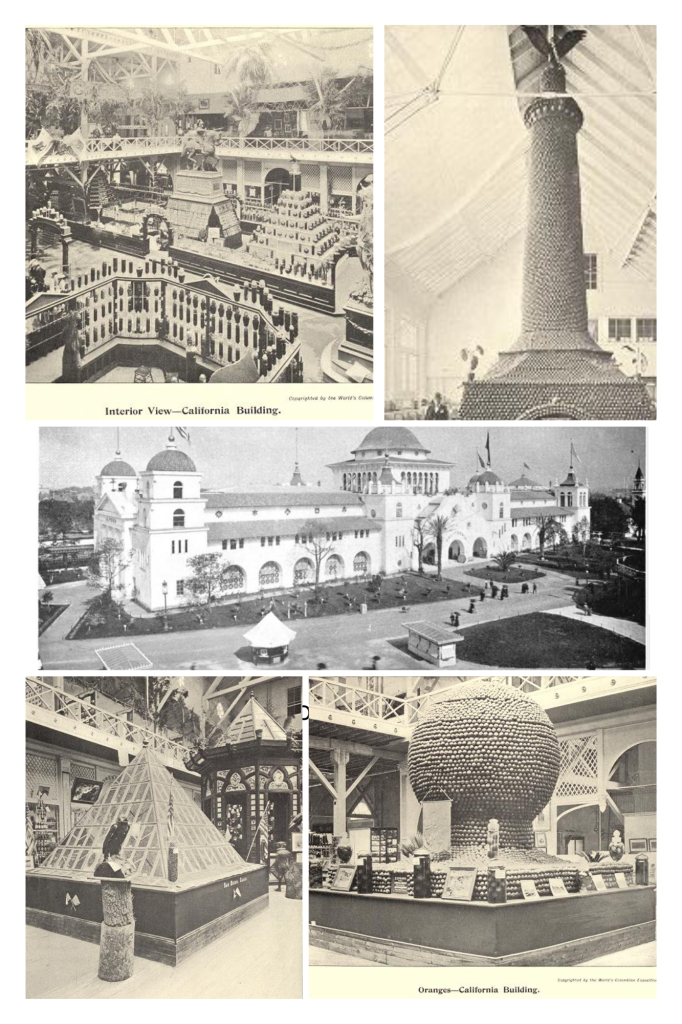

Among the state pavilions, California’s was second in size only to host state Illinois. It stood out like no other (see photos below): architecturally unique with California’s now famous mission/Mediterranean look; three stories tall with a restaurant on the roof serving California food and wine; and landscaped with 30 orange and 20 lemon trees that bore fruit throughout the summer/autumn fair, luring visitors with their citric scents.

Northern California marketed itself with its vast size, its massive trees and its mining opportunities, while Southern California zeroed in on “The Land of Sunshine and Flowers”. Counties from the north had small, individual booths, while Southern California counties teamed up in a central space to showcase their agricultural paradise:

- An elephant made of 15,000 walnuts, topped with a seat of corn, wheat, barley and moss that itself was “strapped” by a belt made of lemons;

- A 28-foot-tall tower of 2,000 olive oil bottles;

- A pagoda weighing 2,000 pounds and made of 83 varieties of beans;

- A “Palace of Plenty” with dozens of types of grains and other fruits;

- A 123-year-old, 50-foot-tall palm tree originally planted by Junipero Serra, the Franciscan friar who founded the California mission network;

- And the piece de resistance, a globe made with 6,280 oranges that had to be replaced every few weeks — so about 70,000 oranges were used during the course of the fair.

It wasn’t just the eyes that feasted on the bounty of food. That delicious, fruity, sweet but slightly tart perfume of lemon and orange trees would tie into the region’s other marketing images: snow-capped mountains, fertile valleys, sandy beaches and blue ocean. Just what Los Angeles and its neighboring counties wanted. In fact, the Southern California World’s Fair Association published a 112-page Land of Sunshine guidebook given out to potential “home-seekers” and touting those virtues. The fair’s own magazine recognized that Southern California “could be brought prominently before the world as the best country for the home-seeker” and praised its fruit showcases as “one of the greatest attractions” of the entire fair.[4]

Every other state, especially Florida and its oranges, was put to shame. “No one can visit the state building without finding a new significance in the phrase ‘The Golden State’,” wrote a reporter for Australia’s Melbourne Age. [5] “Immense trophies of lemons, oranges, walnuts and prunes produce massive effects… The beautiful colored oranges are in striking contrast to the dingy specimens from Florida.”

A reporter for the Florida Agriculturalist concurred. California has “whole orange groves, and waving palms and other plants to greet the eyes of the lovers of tropical scenery. They do not fail to improve every opportunity to advertise their State,” the despondent correspondent wrote. “While alas! Where, oh! where are we?”

How could you not, if you were looking for a change of weather, scenery and employment, fall for California? The Chicago Times put it this way: “There was an air of prosperity and abundance about it all that is seen in no other State building. Great palms waved their green plumes against the roof beams, and the sweet perfume of flowers and fruits made the air heavy with fragrance. Wines and cakes were served during the afternoon, and always, before and after everything else, fruit.”[6]

A Fiesta is Born

That brief exodus of home-seekers from Southern California didn’t take long to turn around. Los Angeles, like Grif, was starting to find its stride. Showing off Los Angeles at the nation’s display case was just the first part of a sales pitch. The second, aimed at giving visitors a reason to stay beyond winter and into spring, was a week-long “La Fiesta de Los Angeles” that included parades, parties and an entire hierarchy of Fiesta queen, knights and subjects.[7]

Imagine an 1890s Los Angeles still mostly drab and dusty during the day and dark at night, with just a few electric lights having replaced gas street lamps and their eerie, flickering flames. The Fiesta, conjured up in 1894, was modeled after Europe’s carnival celebrations and New Orleans’ Mardi Gras. Over five days in April, it brought color, costumes and a sense that happy days were here again.

Mingling downtown with tourists, many of them from Chicago, were proud descendants of Mexico’s rancheros, Chinese immigrants, the tiny African-American community, and the city’s white business elite. Buildings were draped in the Fiesta flags of orange, red and green — representing a farming heritage of oranges, grapes and olives.[8] While much of the region was in flux with subdivisions replacing fields, many areas still had that farm feel. Hollywood, for example, had yet to boom and was home to 25,000 grape vines owned by former Sen. Cornelius Cole. In fact, what later became Hollywood’s Vine Street was so named to honor that heritage.

Ten thousand banners and 30,000 yards of bunting were said to have decorated homes and businesses along the first year’s parade route. Five wagons full of pepper boughs and 25,000 palm leaves covered ugly telephone poles and lines. The opening parade saw 300 bicycles, street cars wrapped in flowers, and floats representing the city’s history, even the 1880s Boom. Angelenos had recovered enough to be able to laugh at a “Busted Boom” float carrying a dilapidated real estate office with a broken safe, empty jug and “for sale” sign.

Fighting for a Free Harbor

By 1895, Los Angeles was again making forward progress — at least that’s how the business elite saw it. A new fortune had been made — one Edward Doheny was lucky enough to discover oil, lots of it, right next to downtown in 1892. And at the Times, owner Harrison Gray Otis was fostering a Merchants and Manufacturers Association as a way to counter labor unions.

It was a time of growing confidence for business, and especially the boosters, who imagined an ever growing, ever important Los Angeles. Otis, in particular, used his editorial perch to rally boosters like Grif. A century later, historian Mike Davis would call this the start of “the most ambitious city-building program in American history” — one that within 20 years had created the world’s biggest manmade harbor, aqueduct and urban electric rail network. “With the immodest ambition of surpassing San Francisco in a generation,” Davis wrote, “they kept Los Angeles on a war footing — fully mobilized for self-promotion and improvement.”[9]

After the world’s fair and fiesta successes, boosters had gained the bravado to take on what had been their greatest ally but which was now holding back their plans to expand business across the ocean. That would be the Southern Pacific railway. Known as “the octopus” for having its tentacles in many places, the SP wanted a deep-water shipping port to be in nearby Santa Monica, where it controlled the rail lines. Most business leaders backed the campaign for a “Free Harbor” in San Pedro — as in not monopolized by the Southern Pacific.

Federal funds had helped dredge the port in nearby San Pedro, but much more money was needed to make it a deep-water port for large ships and for years it seemed like a losing battle. Then, in late 1895, a “Free Harbor League” was formed to step up lobbying for federal help. Its top leaders included Otis, U.S. Sen. Stephen White and George S. Patton (yup, his son would grow up to be that general!).

The port battle would continue four more years, during which time Grif would become one of the league’s several hundred honorary vice presidents. While just a symbolic gesture showing business leaders were against the SP, in Grif’s case it also reflected that he was establishing himself among the elite.

Grif gained even more stature as a founding member of the Jonathan Club, which started in 1894 as a group of Republicans supporting presidential aspirant William McKinley. By 1895, it had turned into a social club that quickly became the place to network. Other members included Otis, as well as tycoons Doheny (oil), Henry Huntington (railway), and William Wrigley, Jr., (chewing gum). Less than a decade later, fellow Jonathans were among those who, at Grif’s trial, described him as delusional and a drunk. Grif’s own lawyers had sought that testimony, hoping to convince the jury that alcohol had driven Grif crazy and that what he needed was hospitalization, not prison.

For Grif, it must have been humiliating to see his peers disparage, even make fun of him. But at the turn of the century, Grif was still at the center of local power. In 1896, he helped kick off the Los Angeles Mining and Stock Exchange by writing its trading rules.[10] And, on behalf of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association, he visited a Utah mining area, reporting back that a proposed rail line from Los Angeles through the mines and to Chicago would benefit local industry.[11]

He also sold the last Briswalter parcel for $150,000. Not only was it the largest undeveloped tract left in the city, Grif made sure that his name was forever tied to the area by creating Griffith Avenue to separate the tract from an earlier, smaller Briswalter parcel.[12] Thanks to Tina, the otherwise land-rich, cash-poor Grif had again pocketed a tidy sum. Of course, he never acknowledged Tina’s importance and he would later reflect that by this time, early 1896, he alone was able to “shape my finances” so as to execute a long-desired legacy. And that happened just before the end of 1896, on December 16, to be exact. He called it his “Christmas gift” to Los Angeles: the donation of 3,015 acres of Rancho Los Feliz for a massive park.

- Rahno Mabel MacCurdy, The History of the California Fruit Growers Exchange, p26. ↵

- Grif's role in founding the Citizen's League is detailed by Donald Culton in “Charles Dwight Willard: Los Angeles City Booster and Professional Reformer, 1888-1914", pp109-112. ↵

- Errol Stevens in Radical L.A. describes Otis' rabid anti-union history. Robert Fogelson, in The Fragmented Metropolis, pp211-212, notes many progressives were well-educated Easterners who had moved to California to escape poor European immigrants and the political bosses that used them. ↵

- California World's Fair Commission, Final Report, p105. ↵

- ibid, pp101-102. ↵

- ibid, p108. ↵

- Some authors argue the Fiesta was more about business leaders distracting workers from organizing into unions. See Mike Davis, City of Quartz, p26, and Errol Stevens in Radical L.A., pp6-10. ↵

- Workman in The City that Grew, pp258-265, offers a detailed, first-hand account of the Fiesta's origins. ↵

- Davis, City of Quartz, pp112-113. ↵

- Land of Sunshine, July 1896, p92. ↵

- Herald, October 22, 1896. ↵

- Times, March 20, 1896. ↵