1 Hitting Rock Bottom

FEBRUARY 16, 1904

___________________________

“Her face was veiled, the soft dark netting like a widow’s weeds hung to her waist. All we could see was a ghostly shadow. From behind the veil, her voice was a whisper we had to strain to hear, and the pauses were long and empty, like falling down a well.”

–Journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns, describing Tina testifying at trial

As gruesome as the assault was — shot in the face, Tina jumps from hotel’s third story window, falls nearly 15 feet onto a rooftop and fractures shoulder in desperate attempt to escape — it wasn’t immediately clear that Grif would ever stand trial. Tina wasn’t sure she wanted to prosecute as it would leave a stigma on their teenage son. Grif was optimistic he could patch things up, and it probably didn’t really sink in until five months after the shooting that he no longer could avoid trial. The proud, self-made man would go on to see many low points during the two weeks of trial testimony, but it was day two that produced the lowest low.

It was on that day, February 16, 1904, that Tina lifted her dark veil for 12 jurors — all men, by the way — to see her disfigured face. Burn scars lined the socket of her right eye. The eyeball itself had been destroyed, and bullet and bone fragments in the socket removed.

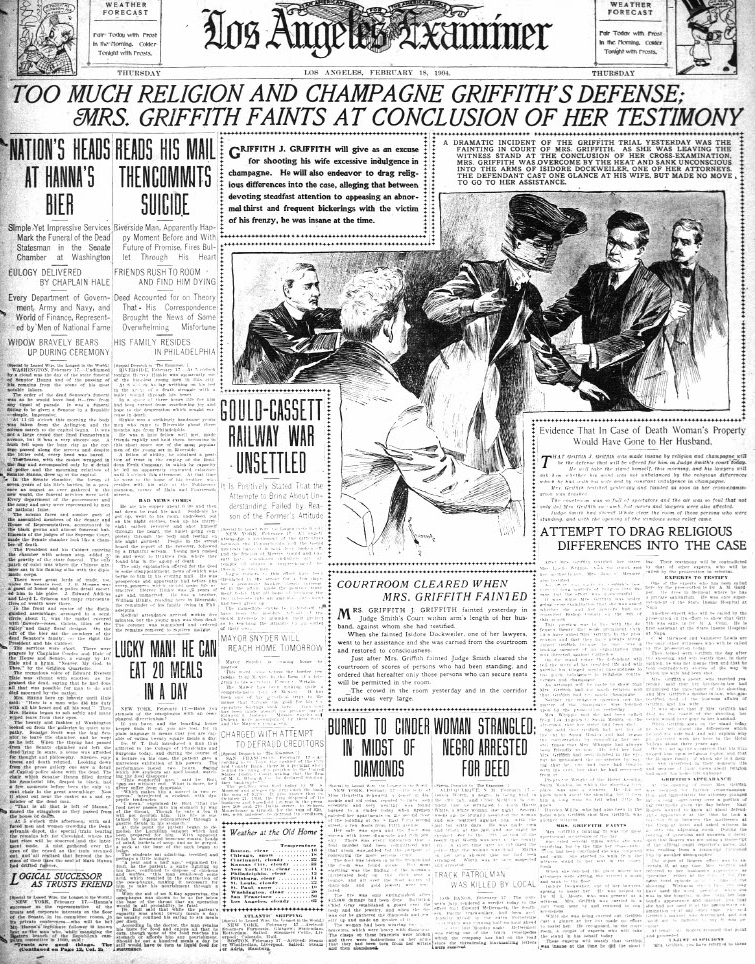

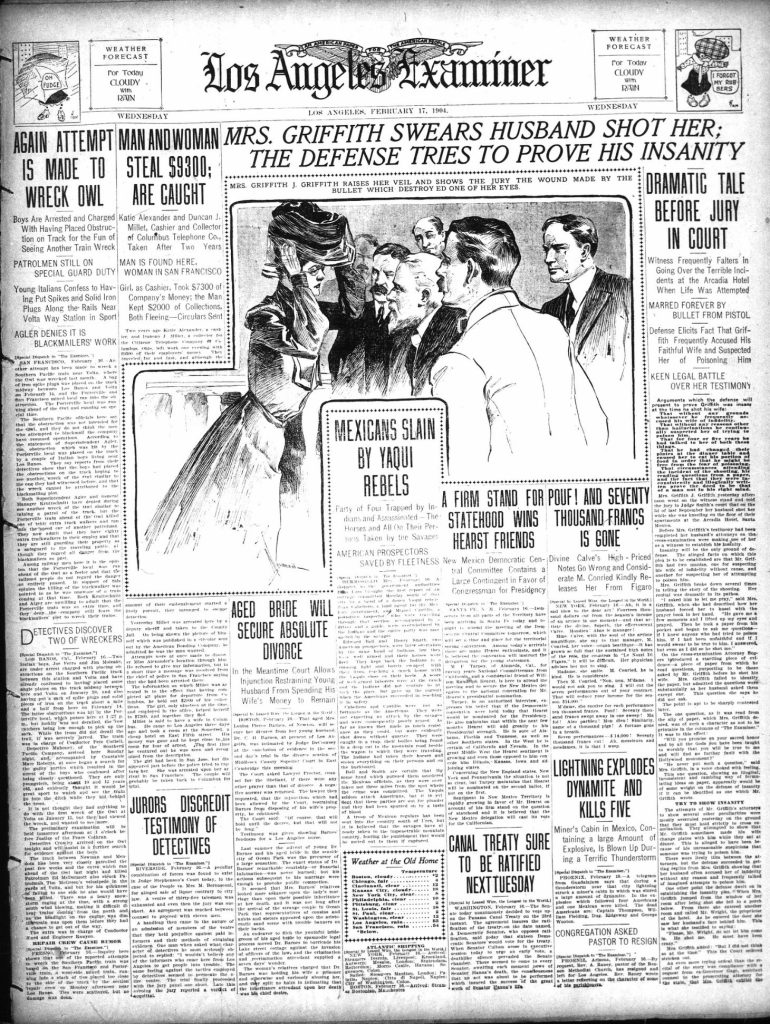

The Los Angeles Examiner, the new, flashy paper in town, captured the moment in an illustration across five of its seven front-page columns:

The Los Angeles Times hadn’t yet turned illustrations into sensational visuals, but its reporters spared no detail. Tina’s “lawyers made Mrs. Griffith get down from the witness stand,” the Times reported, “and show her sightless eye socket to each of the jurors in turn, holding up her veil and dark glasses while each of the twelve looked her scars and deformities critically over.”

Those in the packed courtroom had been waiting for that moment — they had to see it to believe it. Sure, Grif’s associates knew he was cocky and quirky, but shoot his wife? He had given Los Angeles a massive park and had his hands in real estate, local politics, a tile factory, the elite Jonathan Club and even in bringing a baseball team to the city.

When that moment arrived, it was, a Times reporter wrote, “pitiful and one of the most painful incidents that ever happened in Judge Smith’s court.”

A crumpled Grif only added to the pitiful picture. “He sat far down the table, shoved along by his lawyers,” the Times observed, “helpless and impotent, sometimes eagerly fumbling over a bundle of cards he took from his pocket, but more often leaning over the table and watching her with troubled, anxious eyes, his face turning white and red by turns.”

The Ghost in the Courtroom

Even before Tina lifted her veil, the mood in the courtroom was heavy with drama. The first day had started with the last jurors seated and then the prosecution wasted no time in calling Tina to the stand.

“After some delay she entered the courtroom, accompanied by Mrs. Charles L Whipple, her sister, and Mrs. Jennie Mesmer,” her stepmother, the Los Angeles Herald reported of that first day. “Mrs. Griffith was so heavily veiled that her features were not discernable, and she also wore a pair of blue spectacles which entirely covered any disfiguration from the wound which she received. She was gowned in a blue suit and wore a heavy fur collar.”

Years later, the daughter of Grif’s chief trial lawyer recalled having herself been in the courtroom, spellbound when Tina’s attorney called his client to testify. “Mrs. Griffith limped painfully down the aisle,” Adela Rogers St. Johns wrote in her biography of her father, Earl Rogers.[1] “Strange it was to see her pass within a few feet of the bellicose, fidgety, twitching defendant … She did not look at him as she made her way to the raised platform on which stood the witness chair.”

“I have never known such a moment of deathly stillness in any courtroom,” wrote Rogers, who went on to have a renowned journalism career. “We could not fathom what it all really meant to them, the thralldom was so great we couldn’t move, we could hardly breathe. My heart was thumping words to a death march. We made no sign, we said no word, we had no word to say. They had loved each other, married, it seemed stranger to me than anything I had ever known in my short life.

“Her face was veiled, the soft dark netting like a widow’s weeds hung to her waist. All we could see was a ghostly shadow. From behind the veil, her voice was a whisper we had to strain to hear, and the pauses were long and empty, like falling down a well.”

Tina’s testimony had begun with her lead attorney, former California Gov. Henry Gage, asking her to detail everything she could remember about the afternoon of September 3, 1903. “As she faltered out her story, behind the dark curtain, she put a delicate handkerchief to her eyes,” Rogers wrote. Gage “stood close behind her … he seemed only concerned to help this trembling lady, he repeated her whispered answers sometimes in a resonant, unhappy baritone.”

The Los Angeles Express reported that Tina’s “recital of the scene was given brokenly and with sobs that shook her body convulsively. There was scarcely a dry eye in the courtroom and every word of the terrible story was listened to with bated breath.”

Tina recalled that she was packing to head home after a summer at the Hotel Arcadia in Santa Monica when Grif walked into her room and said: “’You will take this prayer book and get down on your knees.’

“I immediately became alarmed and said: ‘What do you mean?’

“He replied: ‘I want you to get down on your knees and swear to some questions I am going to ask you.’ I took the book and got down on my knees.”

Obviously reliving the trauma in her mind, Tina needed a few minutes to compose herself, finally uttering: “Then I saw a revolver in his hand and cried out to him to please put it away. He said: ‘Close your eyes’ in a determined way. I then saw that he meant what he said and I asked him to let me pray. Then I raised my eyes and prayed, as I felt that I was in the hands of a desperate man.

“After I had finished praying he asked me a few questions” — starting with whether the benefactor who left Tina his estate had been poisoned in her home. Not waiting for an answer, and after pointing out that “I am a dead shot”, Grif asked if Tina had tried to poison him. “I said, ‘You know I have not, papa, I have never harmed a hair on your head.’ The third question was whether I had been untrue to him. I replied: ‘You know that I have not’ — and with that I was shot.

“He immediately jumped upon me, and as I broke away I said: ‘Oh, why did you shoot me?’ and backed toward the window. I went out on my back. My first thought was to get out of that room, whether dead or alive it did not make any difference. As soon as I struck the room below I picked myself up as well as I could and went to a room. I raised the window and went to a washstand to stop the flow of blood.”[2]

Earl Rogers was content to let her paint a horrific picture — until she got to what she had told the hotel owner, who had rushed to her aid with Grif right behind him. “For God’s sake don’t let him in, he has just shot me. I don’t want him to come in. He must have been crazy,” she testified, repeating in so many words what she had said at the pretrial hearing. But she quickly noted that the “crazy” part “I added in an off-handed way. I did not think so at the time.”

At that Rogers, out of his chair and almost shouting, demanded that “I did not think so at the time” be stricken from the record since it ran counter to her pretrial statement that he must have been crazy. The judge agreed, and Rogers had locked in his strategy: Alcohol had driven Grif crazy and thus he wasn’t accountable for his actions.

Magnified by the media

Mind you, all this courtroom drama was just day two, and for two weeks this was the one story Angelenos talked about. This was pre-television, and even photos were not very common yet, but what newspapers did have were big headlines, illustrations and newsboys on street corners hawking the day’s top stories.

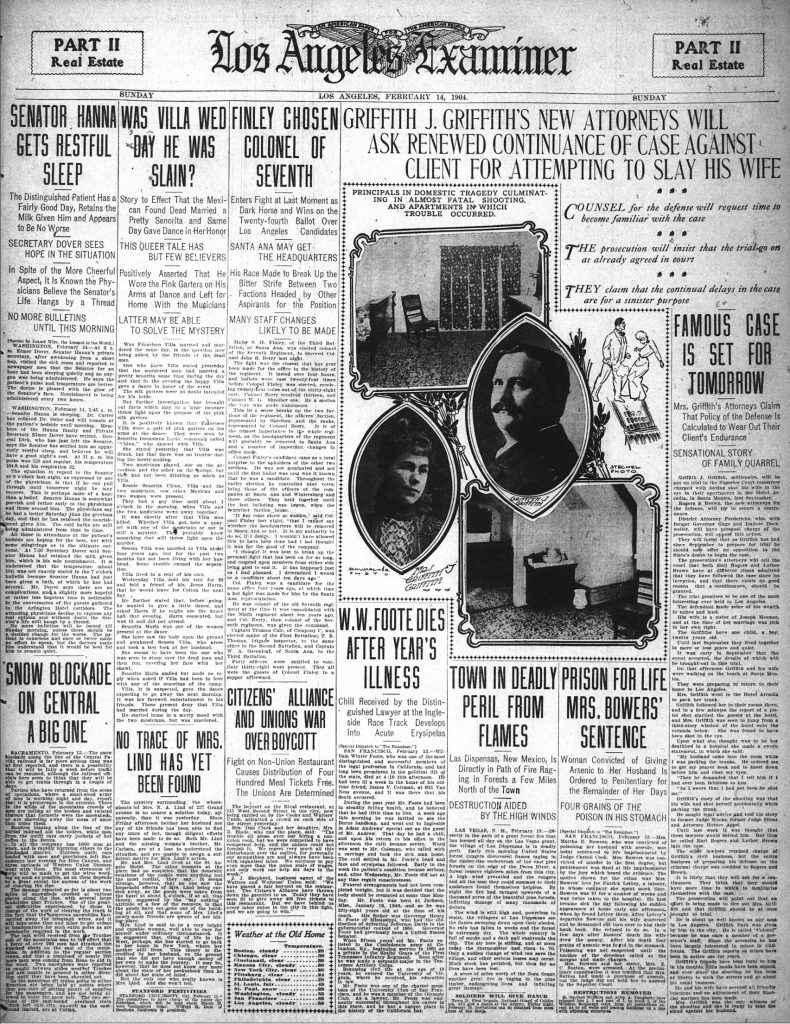

Newspaper readers were also being introduced to sensational stories, what would become known as yellow journalism, a style embraced by William Randolph Hearst as he expanded his publishing empire from San Francisco. His Los Angeles Examiner had entered the local market just six weeks before the trial started and seized on the Griffith drama as a way to stand out. From the start, the Examiner led the news pack with more coverage in terms of words, illustrations, large headlines and photos. Portrait photographs of Grif and Tina (see below) anchored its preview on the day before the trial (Valentine’s Day, no less), along with photos of the hotel suite where the shooting took place — and a sketch of a man holding a smoking gun as a woman falls back.

By contrast, its major competitors, the Times and Herald, were slow to start. The Times relegated day one to two paragraphs between the sports roundup and a dyspepsia ad, and the next two days were in Section II under the drab roundup of city government called “The Public Service – Official Doings”.

Whereas the Times had a strong following among the local business community, the Examiner, like all Hearst publications, positioned itself as a working man’s paper, and that meant zero sympathy for Grif. So while the Times and Herald always referred to Grif by his honorific (some would say invented) title of colonel, the Examiner did not once. Instead, in each day’s report it introduced him as “Griffith, the capitalist,” or “Griffith, the millionaire”.

As powerful as words can be, the illustrations, photos and overall story packaging made an even bigger impact. And while the Times and Herald at first resisted that type of sensational coverage, the Examiner was all in — keeping the story on its front page for two weeks. Tina’s lifting of her veil was followed the next day with Tina fainting in court — another five-column illustration along with this two-deck headline across all seven columns:

Self-Destruct Strategy

More testimony, and the verdict, will follow a bit later, but the “religion and champagne” headline calls for an immediate explanation. Earl Rogers felt that the only way to save Grif from prison was to destroy his good name — show him as an egotistical drunk who had temporarily lost sight of right from wrong. Temporary insanity would be the strategy built on Grif’s relationship with the Catholic Church and booze. Whiskey, champagne, martinis — anything with alcohol.

Just 34 years old but already a local celebrity for his use of forensic science, courtroom props, a dashing wardrobe and an actor’s delivery,[3] Rogers at first didn’t want to touch the case, his daughter recalled, because he knew Grif and thought of him as a “midget egomaniac”. [4] (Grif was a bit short at 5’6”, and his portly girth made him look even smaller.)

But Rogers had also learned that some of Grif’s acquaintances — from barmen to members of men’s social clubs — spoke of a secret side. Grif was said to consume quietly and copiously. He also was known to rant that Catholics — whose faithful included his wife and her parents — were trying to kill him, a Protestant, for his money. Could alcohol have made him temporarily crazy?

After a barbershop manicurist told him Grif was a chronic nailbiter, Earl Rogers paid Grif a visit, not to talk about the case, but to see his fingernails for himself, Adela Rogers later wrote, adding that it was those fingernails that finally convinced Rogers to take the case.

When Adela questioned what that had to do with anything, he raised his voice. “Didn’t anything inside you tell you that a man Griffith J. Griffith’s age, with millions in the bank, a business he’s supposed to be a genius at, a handsome wife — if he bites his nails down to the quick there has to be a reason? Something has to be very wrong with him?”

Alcohol, Rogers told his daughter, had turned Grif into a modern Jekyll & Hyde. Rogers even read her passages from Robert Louis Stevenson’s masterpiece — the monster Hyde “gnawing his nails”, and Dr. Jekyll’s potion making him “a slave to my original evil, at the moment this braced me and delighted me like wine.”

What Rogers never acknowledged, though his daughter referred to it throughout his biography, is that he too was under alcohol’s spell. Though charming, eloquent and theatrical, he died divorced, penniless and alone in 1922 at age 52 of liver disease. Of the 77 homicide cases Rogers defended, Grif’s was one of only three Rogers ever lost[5] — and it haunted him, Adela wrote.

In 1903, however, both Grif and Rogers were in their prime and both were Los Angeles elite. It was also the Gilded Age, and both men had larger than life personalities in that era of unique transformation and wealth. They were set up for success, yet both succumbed to alcohol.

- Adela Rogers St. Johns, Final Verdict, pp227-228. ↵

- Los Angeles Times, February 17, 1904. The various newspapers covering the trial often had slightly different quotations of witnesses and lawyers. When choosing which ones to use here, I've relied on the reporting that was most detailed at the time. ↵

- Mike Trope, Once Upon a Time In Los Angeles: The Trials of Earl Rogers, pp19-21. ↵

- Rogers, Final Verdict, p221. ↵

- See triallawyerpotraitgallery.org/earl-rogers. ↵