3 Chasing the American Dream

1866 to 1882

_______________________

“Our esteemed friend and townsman has recently been made the recipient of a very handsome present.”

— The Eureka Sentinel on August 17, 1879, describing how Grif, now a mine superintendent, was rewarded by his employers with a carriage and two horses

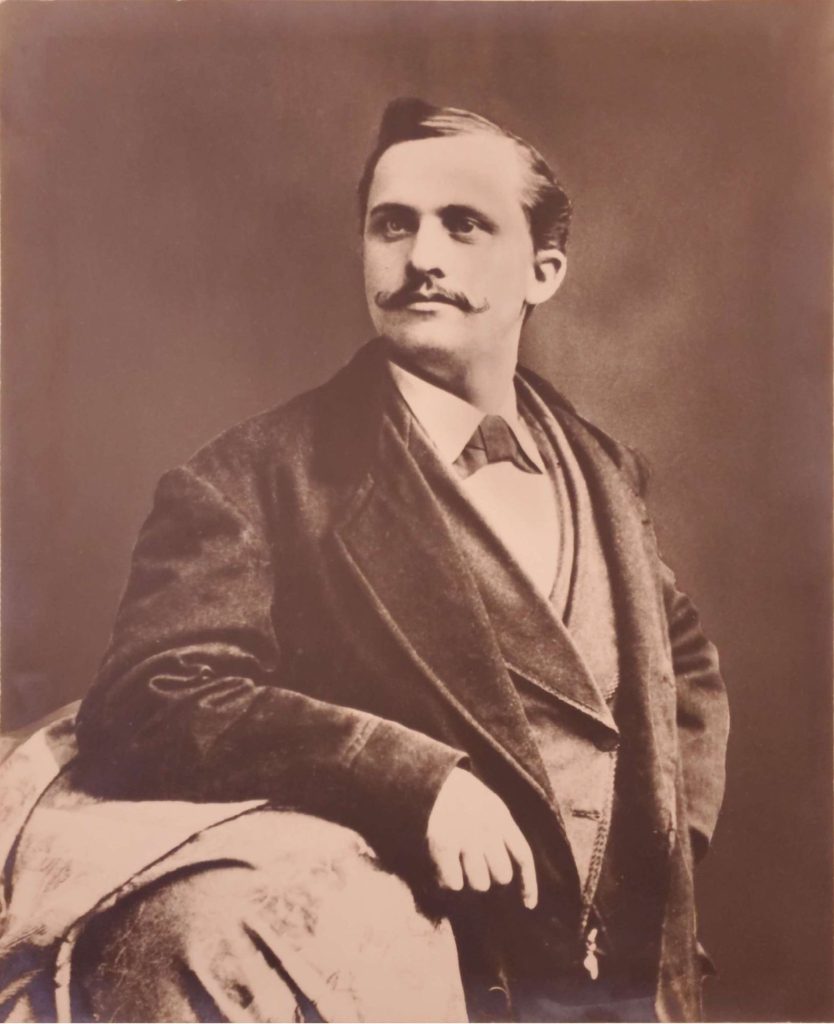

Grif’s American experience began when he seized the chance to leave his home in Wales, United Kingdom. By his own account it was 1866 and he was just 16. He had been born into a poor family and, in his autobiography, acknowledged that as a child he had had little love and less stability. Due to his mother’s ill health, he lived with his grandparents until they both died and then, around age 9, moved around between his father, an aunt and other relatives.

Given those circumstances, he “immediately accepted” an invitation from an uncle visiting from the United States to join him in Ashland, Pennsylvania. He stayed with his uncle’s family for nearly two years until he met a couple in nearby Danville whose son had died in the Civil War. A deal was struck where, for the next five years, Benjamin and Jane Mowry would give Grif room and board in exchange for chores. He finished high school there and, more importantly, found mother and father figures who, by Grif’s own account, gave him love and a moral compass.

Throughout his life it was rare for Grif to comment lovingly about anyone, so his lengthy description of the Mowrys, while not dripping with emotion, shows how appreciative he was. “I grew up in their affections, and they in mine, so that our conduct toward each other was more like affectionate parents and child than of strangers,” Grif wrote in his autobiography. The devout Methodists, and Grif, would nightly read bible passages. “’Do unto others as you would have others do unto you’, was ever uppermost in their minds, and they practiced what they preached… I had before me a constant example of the highest standard of Christian morality known to man.”

Mining His Own Business

After five years with the Mowrys, Grif set out on his own by signing up for journalism training at a New York City institute. From there, he worked briefly in Pittsburgh, first at a carriage maker and then for a brewers’ association. In 1873, he made his big move west, to San Francisco. There he met the owners of the Daily Alta California, the dominant newspaper on the West Coast, and soon was its mining reporter. (Grif knew a bit about mining given his father’s business of hauling iron ore.)

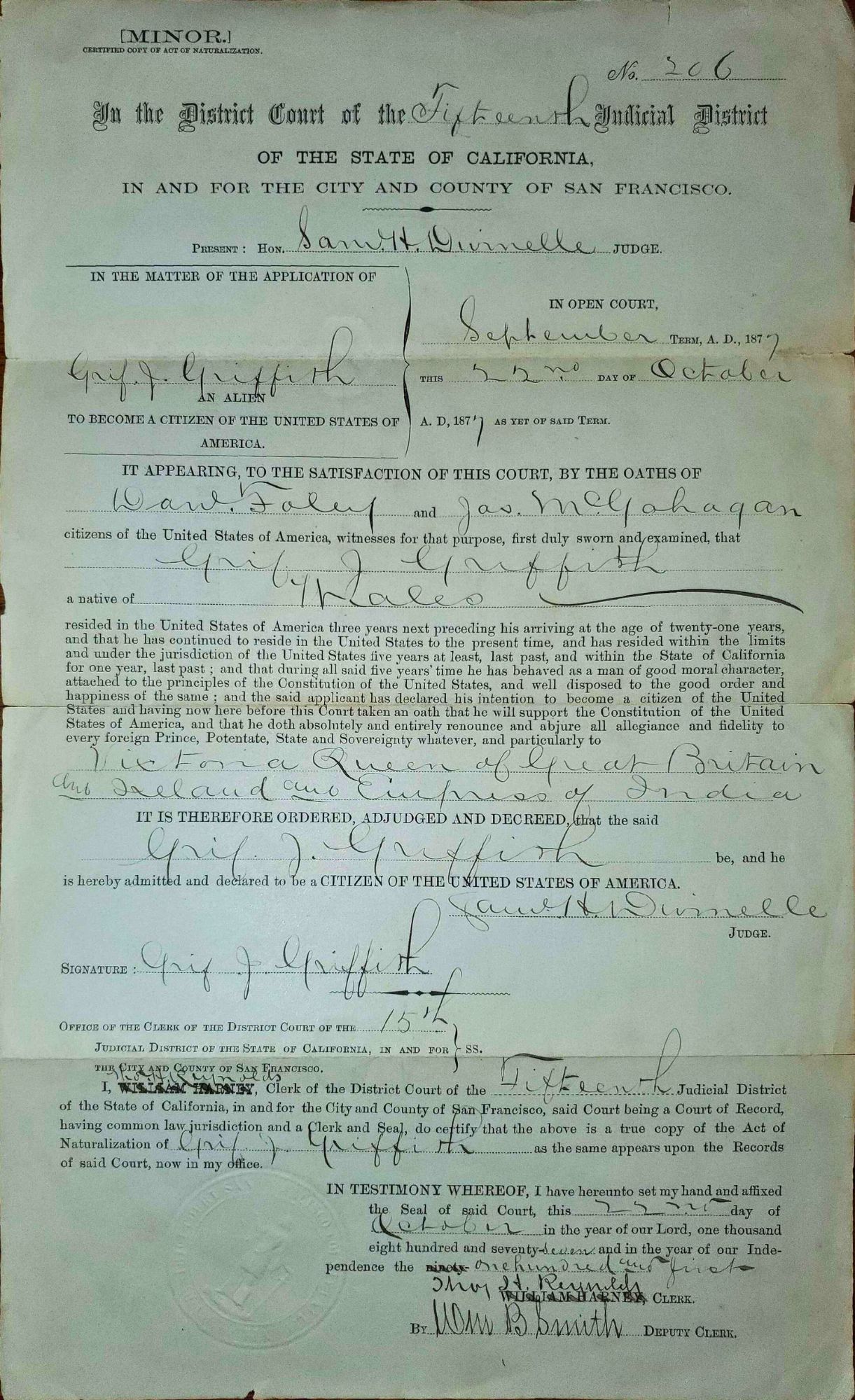

In 1877, he became a United States citizen and by that time he’d also developed a side job of preparing reports on prospective mines — certainly a potential conflict of interest if ever there was one. As a journalist, he was supposed to be a credible, honest source of information, but as a hired hack he had an incentive to exaggerate so that his employers could sell stock to trusting investors — and earn Grif a nice bonus. He was especially proud that his first major report was “so satisfactory and profitable to the syndicate” that he received $1,000 a day for three days work, plus a $5,000 bonus — the latter well over $150,000 in today’s dollars.[1]

It was an era of speculative euphoria driven, in part, by encouraged exaggeration and Grif was not alone in that practice. Among the many who partook was Mark Twain, aka Samuel Clemens, during his stint as a newspaper editor in the mining town of Virginia City, Nevada. It was the “friendly custom,” he wrote in his book Roughing It, for miners to give reporters some stock shares in their mine so as to get newspaper publicity.[2] “If the rock was moderately promising, we followed the custom of the country, used strong adjectives and frothed at the mouth as if a very marvel in silver discoveries had transpired.” Even if no good ore had been found, Twain would publish things like “it was one of the most infatuating tunnels in the land; (we) driveled and driveled about the tunnel till we ran entirely out of ecstasies — but never said a word about the rock. We would squander half a column of adulation on a shaft, or a new wire rope, or a dressed pine windlass, or a fascinating force pump, and close with a burst of admiration of the ‘gentlemanly and efficient Superintendent’ of the mine — but never utter a whisper about the rock. And those people were always pleased, always satisfied.”

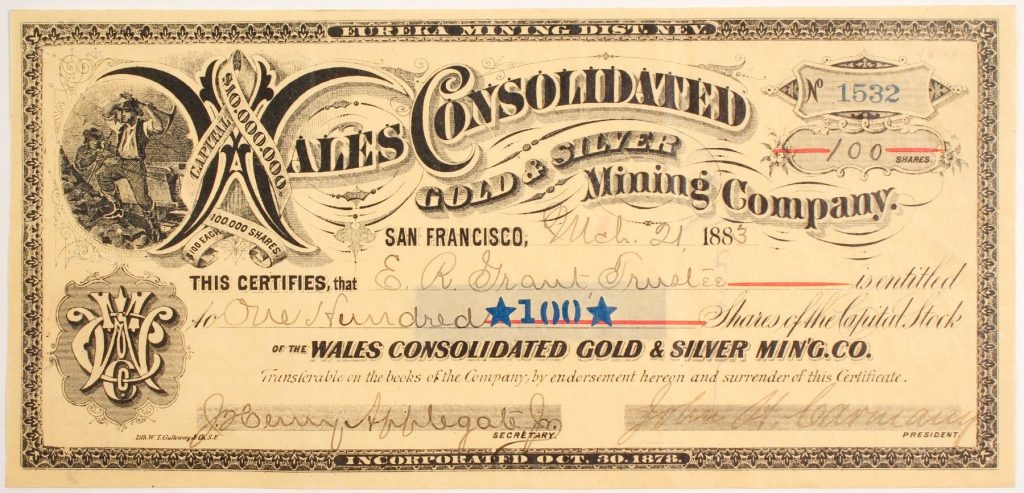

Grif himself soon managed several prospective mines, the most promising of which was in Eureka, Nevada. The Wales Consolidated, of which Grif was superintendent, started out well enough. The game back then was to get investors to buy stock in a mine well before anything of value was produced, thus creating profit for the initial investors even if the mine later didn’t deliver silver or gold. Every mine, Twain wrote, “had handsomely engraved ‘stock’ and the stock was salable, too. It was bought and sold with a feverish avidity in the boards every day. You could go up on the mountain side, scratch around and find a ledge (there was no lack of them), put up a ‘notice’ with a grandiloquent name in it, start a shaft, get your stock printed, and with nothing whatever to prove that your mine was worth a straw, you could put your stock on the market and sell out for hundreds and even thousands of dollars. To make money, and make it fast, was as easy as it was to eat your dinner.”

Part of that strategy was to show confidence in one’s man on the ground, aka superintendent. In Grif’s case this included gifts from his capitalist backers that the Eureka Sentinel trumpeted as part of the marketing campaign. “Our esteemed friend and townsman,” the newspaper wrote on August 17, 1879, received a “boss present” from his backers: a double-seated carriage, along with a team of horses. “The carriage is thoroughly put up, having steel axles and tire, and a top covering that can be removed at pleasure.” The Sentinel added that, only a few weeks earlier, the same capitalists had shown Grif gratitude by giving him a gold watch, chain and locket.

The Wales’ stock price on the San Francisco Stock Exchange would fluctuate wildly as rumors of poor ore triggered sell offs, while Grif would rebut with promising reports. It all came to an end for Grif in 1881 when a suspicious fire in the mine shaft ruined the site and he cashed out in early 1882. Grif refers to this in his autobiography as having been “a very promising speculative property for some time” but others would accuse him of fabricating its potential. Even the Sentinel eventually turned its back on Grif, writing years later that Wales was essentially “fake” and that the fire “relieved Griffith from a rather embarrassing position, as later developments conclusively showed little ‘pay’ ore in the Wales property.”[3]

It’s probably not a coincidence that Grif didn’t move back to San Francisco, but instead set out first for Chihuahua, Mexico, and its silver boom, and then for Los Angeles, where he had no reputation to protect. He was also intrigued by the potential of southern California and, by the end of 1882, he had found his happy place: the Rancho Los Feliz.

- Dollar comparisons in this book reflect purchasing power and are based on inflation, i.e. the U.S. Consumer Price Index, see measuringworth.com ↵

- Mark Twain, Roughing It, pp307-308. ↵

- Eureka Sentinel, September 12, 1903, and February 19, 1904. ↵