2 Climbing to a Cliff

JANUARY TO AUGUST 1903

______________________________________

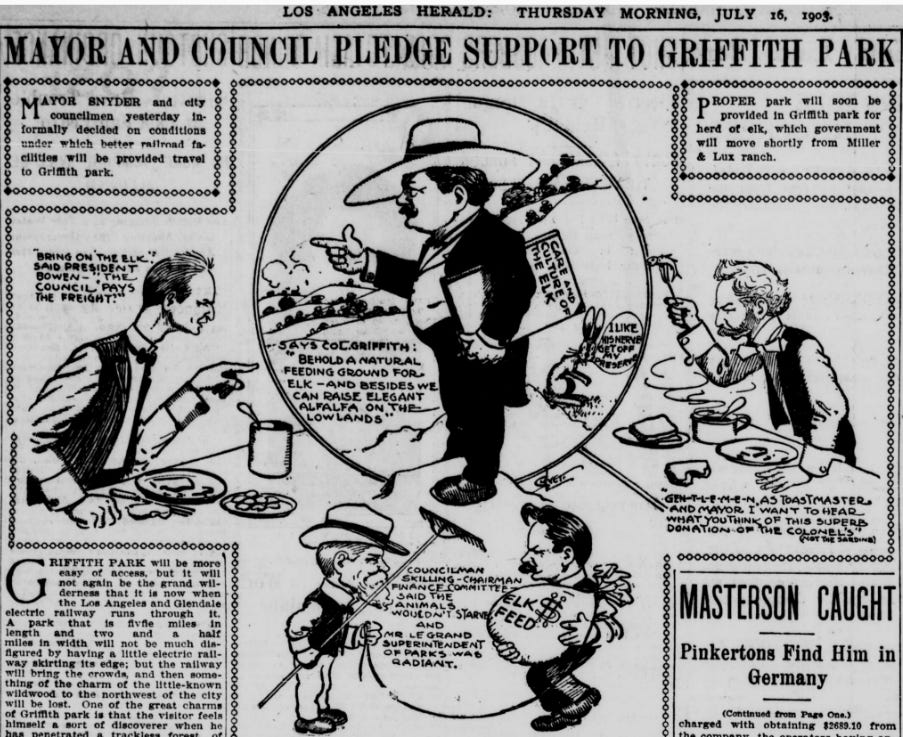

“We owe it to Colonel Griffith to take a proper care of this gift, in that way to show our appreciation of it.”

— City Council President William Bowen at a Griffith Park gathering on July 15, 1903

Grif’s fall came quickly and unexpectedly in large part because, before hitting bottom, he had made a mighty ascent in a short period of time. For much of 1903, he was one of the preeminent “boosters” promoting Los Angeles to tourists and investors. He had built a vast tile factory, had been dubbed mayor of Hollywood for helping develop what had been a farm town, organized one of the first wide, graded avenues in the region, and endorsed plans for a funicular to the highest peak in Griffith Park. He was also having a family burial plot built at great expense and at a non-Catholic cemetery — both much to Tina’s disapproval.

As for Griffith Park itself, Grif in February was appointed by the mayor to the Board of Park Commissioners — not only a reflection of all the hard political work he’d put in over the years, but recognition that his complaining had been heard. Complaints about what? It turns out the city had made no improvements to the park since its donation some six years earlier and, even worse, had turned a blind eye to people illegally hunting, cutting down trees and excavating gravel.

Grif now had a chance to turn that around. Within a few months of being appointed a commissioner, a road had been carved through the park to entice motorists, a plan was in the works to bring in a herd of elk, and city fathers rallied around their role-model philanthropist. “We owe it to Colonel Griffith to take a proper care of this gift, in that way to show appreciation of it,” City Council President William Bowen told his peers at a park gathering on July 15 that included a motorcar tour of the park’s new “driveway”.[1]

In short, Grif was putting together the most gilded year of his Gilded Age.

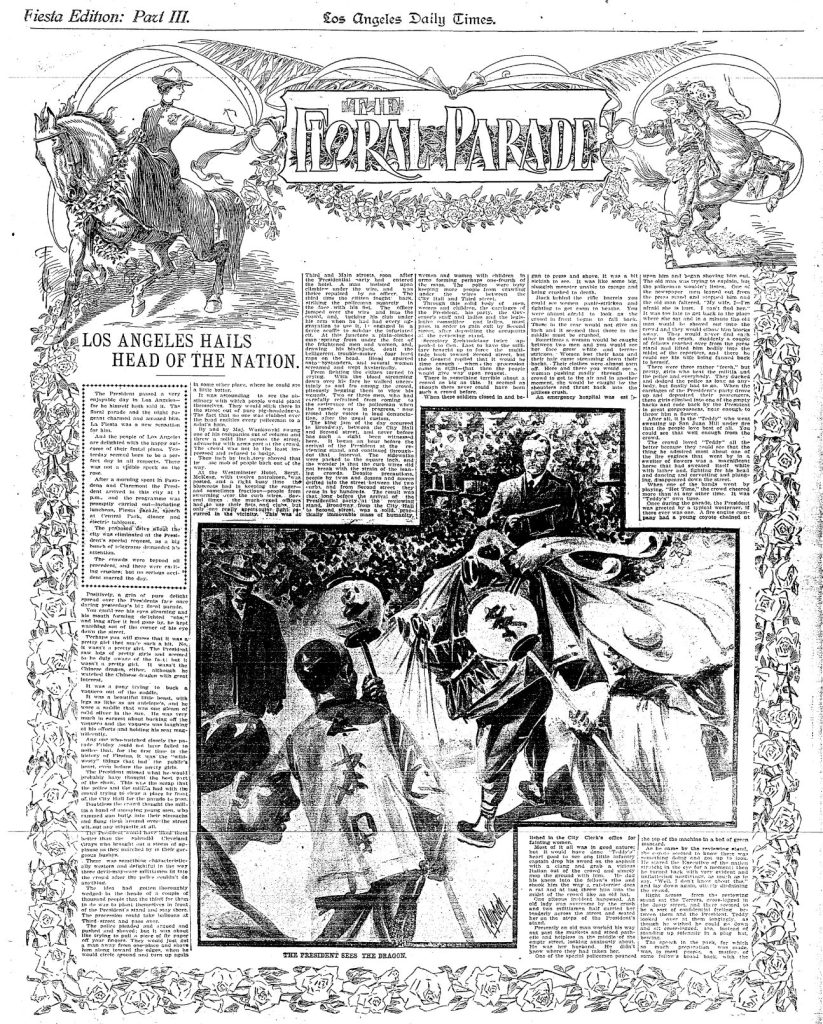

Los Angeles, too, was in full growth and full of the optimism that brought in the 20th Century three years earlier. The social, and political, event of 1903 — President Teddy Roosevelt’s visit on May 8 — proved a coming out party of sorts. City fathers moved the annual Fiesta de las Flores celebration to coincide and did not disappoint the president: American flags, red-white-and-blue bunting and Teddy portraits decorated downtown as dozens of horse-drawn carriages festooned with tens of thousands of flowers made it across the mile-long parade route.

But the highlight, the statement that Los Angeles had grown up, was a second parade — this one at night and under the magical spell of electricity, which was still awe-inspiring as a miracle technology. Fifteen floats were draped in flowers and, more impressively, 5,000 incandescent lamps. The floats sat on top of flatbed rail cars running on the electric trolley line. Angelenos had never seen anything like it, each display lit up and piercing the darkness while seemingly floating along the route. It was, the Times wrote in a special Fiesta section, “nature’s great floral symphony played by man’s orchestra of light.”

The floats told the city’s updated creation story: the first on the route was “Desert Sunset” — a scene of dry sand, rocks, bones. The picture of death. That was followed by “Irrigation” — a scene of green pastures, crops, flowers. The picture of life. Nearly every float was a flower or crop that thrived in the region as long as water was available. The show was “a triumph of the modern and a fit emblem of this new West,” the Times gushed. “It was left for the American pioneer to build the Southwest, for American science to make a garden of the wastes.”

That’s exactly how Teddy Roosevelt saw it, too. In his speech before 50,000 Angelenos, he talked of America’s growing might and how it needed two things to continue: a stronger Navy (plus a Panama Canal, then under construction, to control navigation) and irrigation. “You have made this part of California blossom,” he crowed, having seen it firsthand as his presidential train earlier passed through thousands of acres of oranges and other crops.

Teddy’s visit and praise were affirmation that Los Angeles had made it, and so had recent arrivals like Grif. Over the previous two decades, he and a few others had taken the opportunity to shape a city and make fortunes. They didn’t invent the Gilded Age, but they certainly crafted their own gilded arcs — ascending quickly through society, though in Grif’s case it would lead to a cliff.

- Los Angeles Herald, July 16, 1903. ↵