4 Oh, Happy Days at Los Feliz

1882 to 1884

___________________

“Taken altogether I possessed the finest collection of blooded stock in this section of the country, and one which justified the contemplation of it on my part with pardonable pride.”

— Grif in his autobiography describing how he stocked Rancho Los Feliz with quality animals and crops

Moving to the remote Los Angeles of the 1880s was the perfect place to re-invent oneself. Over the next 20 years, and without anyone knowing exactly how he had made his earlier money, Grif would dabble in ranching, money lending, real estate, local politics and even industry, all while climbing up the ladder of the local elites.

In his autobiography, Grif said he first visited Los Angeles in 1873. While he was “deeply impressed with the great possibilities of this place”, he also felt it still too limited, especially compared to bustling San Francisco. “I found Los Angeles a sleepy sort of Mexican town of about 6,000 to 7,000 population,” he wrote. “About nine-tenths of its inhabitants seemed to be Mexicans or Indians.” And the town was still hard to reach, accessible from San Francisco only by steamboat, as trains had yet to connect southern California to the rest of the country.

In August 1881, while en route to a silver mine investment in Mexico, Grif again visited Los Angeles — this time after the Southern Pacific railway in 1876 had blasted through the San Fernando hills with what was the world’s fourth longest tunnel at the time.[1] Grif was impressed. “Its white population had increased and it was beginning to show some enterprise,” he wrote, implying in typical white settler fashion that the Yankee spirit had been missing among the locals — mostly native Americans, Mexican Americans (California had been part of Mexico until 1848) and Californios (typically descendants of earlier settlers from Spain).

Grif added that a year later he sold part of his Mexican mine interest — excellent timing as the silver market would soon crash. He celebrated with a trip to Europe. On the way back he visited his beloved Mowrys, found them destitute, and ensured they were financially stable the rest of their lives. On their deaths, he even paid for their cemetery costs, crowning their plots with an 18-foot-tall spire.

The small town grows up

Grif returned to Los Angeles a second time and now with $50,000 in his pocket (about $1.5 million today), according to a September 23, 1900, profile in the Herald on how he made his early money. It was late 1882, the town was still small, around 15,000 people, and had its small-town quirks: dusty, dirt streets; a stagecoach to San Diego that took 23 hours; sporadic flooding of the Los Angeles River; and “quaint” issues like the saloon keeper put on trial for operating on a Sunday only to be acquitted after helpful testimony from the mayor.[2]

But 1882 was also a year that saw Los Angeles quickly modernizing:

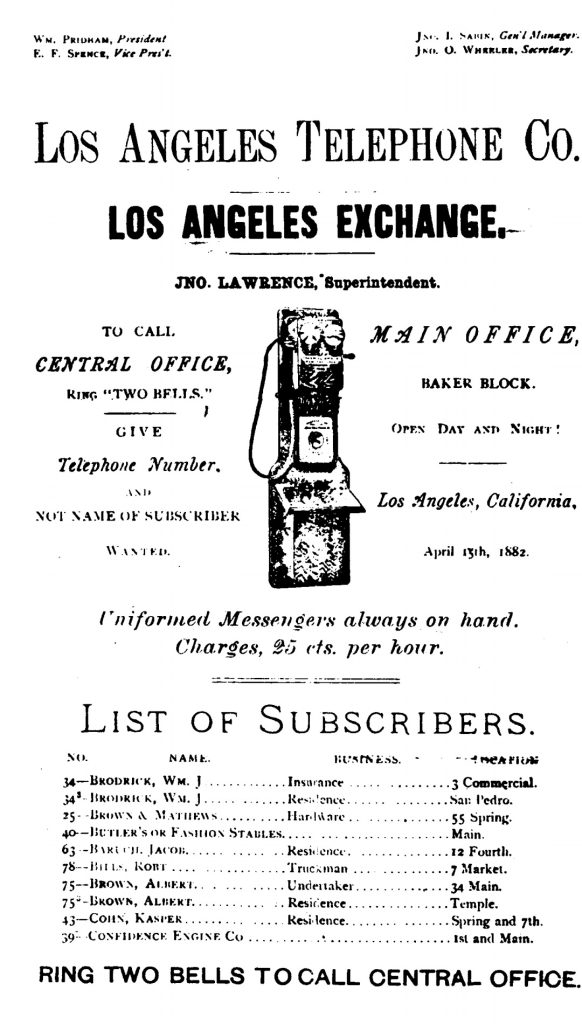

- The first telephones were introduced, connecting to one another through an operator switchboard. The first subscribers included an insurance agent, a hardware store and an undertaker. “Many people were a little doubtful about this eerie invention,” recalled Boyle Workman in his book The City that Grew, but soon it was simply taken for granted[3];

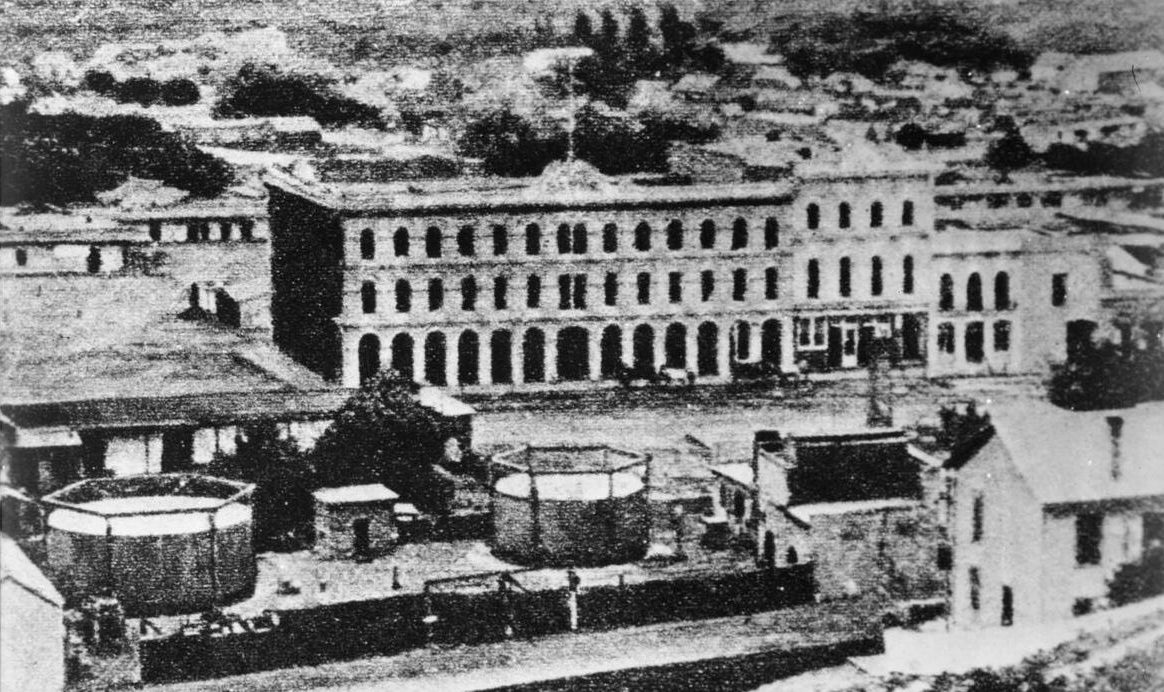

- A new tallest structure (the stately Nadeau Hotel at four stories) was built, and by year end “quite a building boom prevailed … the adobes began to be outnumbered by frame and brick buildings,” the Times later recalled.[4] Within two years, some 2,000 residences and 200 stores had been built.

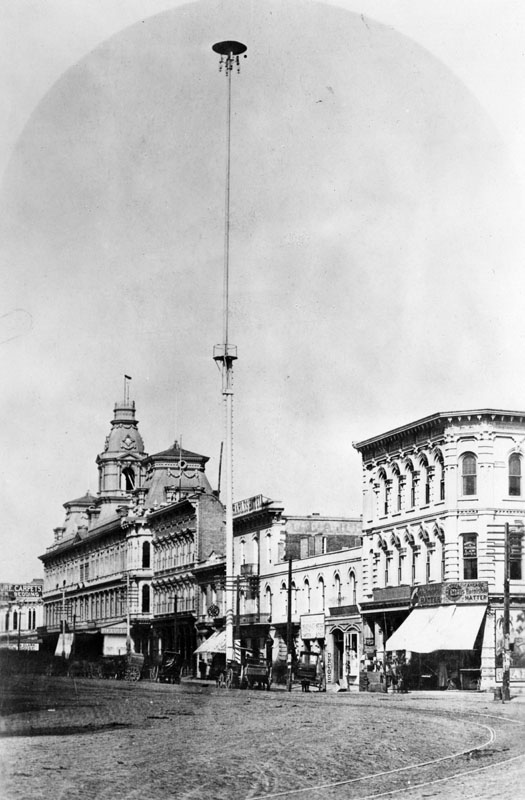

- Seven 150-foot-tall towers introduced electric lighting just in time for the new year in 1882. Over time, 240 poles were scattered around the city. These were giant masts standing much taller than any building, and casting a wide light. [5] Hard to imagine today, but electric lighting did have its critics, especially the gas company, whose competing gas lamps provided only a weak light. One of the gas lobby’s craftier arguments was that the brighter light would not flatter female complexions. It was also said to “be bad for the eyes, producing color blindness,” noted Workman. “It was accused of causing optical illusions, of magnifying objects.”[6]

More modernity followed. In 1883, the U.S. Postal Service introduced home mail delivery, and in 1884 a 1,500-seat theater opened downtown. That year also saw Ramona, Helen Hunt Jackson’s novel of California’s Spanish mission era, become a national bestseller; and East Coast readers were enthralled by dispatches from Charles F. Lummis, who wrote about Los Angeles after walking 3,507 miles to get there.[7] Soon after came the first big success in marketing, or “boosting”, southern California: Local oranges showcased at the New Orleans International Exposition topped those from Florida.[8]

Happy Days at Los Feliz

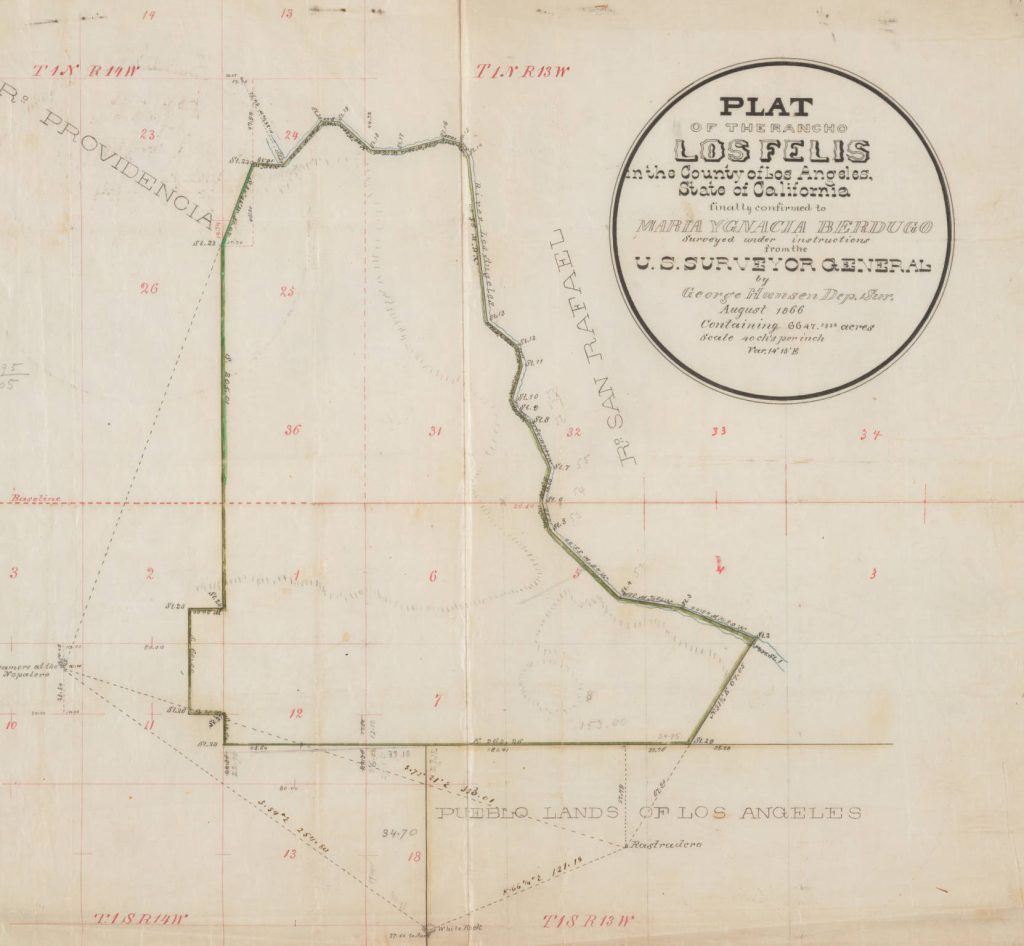

Grif got ahead of those growth years when, arriving in 1882 flush with cash and still in his 30s, he started scouting for land to buy. He soon found the Rancho Los Feliz — or better said the 4,071 acres left from an original 6,647-acre land grant, one of many made decades earlier by Spain when it colonized California from its base in Mexico. Named after the Spanish soldier who received the grant, the rancho had a pleasant translation to English: Ranch of the Happy.[9]

Even those who have never been to Los Angeles will probably have seen part of the old rancho in movies: the oft-filmed Griffith Observatory today sits in the middle of what was the rancho, and the iconic HOLLYWOOD sign sits just west of Grif’s property but on land that was part of the original Los Feliz grant.

Bundling up all the foothills closest to town, Grif’s 4,071 acres also had some farmable flat lands and, more importantly, the Los Angeles River ran along its northern and eastern flanks. The deed was transferred on December 8, 1882, but how much Grif paid is a mystery. His son, Van, later said it was $50,000, but no paper trail exists.[10] What is known is that the smaller Los Feliz tract west of Grif’s had sold earlier for $26,500.[11]

In his autobiography, Grif wrote that he spared no expense to build his rural fiefdom and expressed “pardonable pride” as he “possessed the finest collection of blooded stock in this section of the country.” At its peak, he said, the ranch had 6,000 sheep, 50 horses, 150 head of Holstein cattle, hundreds of Berkshire hogs, and crops that included alfalfa, corn, beans and barley.

In 1883, he gave himself another European vacation, this time viewing magnificent parks that, he later wrote, would inspire him to think of Los Feliz as a perfect public space. For now, however, Grif was all about growing his farm and ranch. On his way back from Europe, he visited his family in Wales and, finding them no better off than when he had left them, encouraged them to join him at Los Feliz. And so, starting in 1884, his father, stepmother and siblings did just that — though over the following years relations between the nouveau riche Grif and his poor relations were not always amicable.[12]

A Wealth of Water

Grif’s first big return on his Los Feliz investment came not from farming or ranching but from a commodity that cost him nothing but meant everything to Los Angeles: water.

Just as moving to Los Angeles when he did was perfect timing, so too was his choice of buying Los Feliz. Two years into his gentleman farmer era, a growing desert town desperate for water offered him $50,000 for rights on his five-mile stretch of the Los Angeles River.

Grif later wrote that “private speculators” had offered him $75,000, but that he turned it down because “I deemed it for the best interest of all parties to sell it directly to the City of Los Angeles.”

Some would later call the city foolish for even making the offer, but earlier court rulings had established that the water rights belonged to Grif, not the city. And you could say that, by taking the lower offer, Grif had made his first grand act of philanthropy to his adopted hometown.

A century later, the chief historian of Griffith Park noted that “it was a perfect mix of business and philanthropy” for Grif. “As a philanthropist he saved the city considerable money in litigation costs,” Mike Eberts wrote in Griffith Park: A Centennial History. “As a businessman, he was able to pocket $50,000.”[13]

- Herald, May 2, 1876. ↵

- Times, December 4, 1891. ↵

- Boyle Workman, The City that Grew, p195. ↵

- Times, December 4, 1891. ↵

- For fascinating images of this transition see the Water and Power Associates website. ↵

- Workman, The City that Grew, pp203-205; see also Harris Newmark, Sixty Years in Southern California, p535. ↵

- Grif and Lummis were among the white settlers who changed the face of Southern California, what Jessica Kim in Imperial Metropolis, p5, describes as the "Anglo ascendancy". ↵

- Daily Alta California, April 17, 1885. ↵

- Eberts in Griffith Park, pp11-20, chronicles the Rancho Los Feliz's history prior to Grif's purchase. ↵

- Rhoda Williams Marshall, "What Were Colonel Griffith's Idea on Wealth and How Did He Acquire and Use His Money", p7. ↵

- Times, August 6, 1882. See also Eberts, Griffith Park, pp35-36, for more about the price mystery. ↵

- Grif's birth mother moved to live with relatives in Pennsylvania and Grif left no indication if he maintained a relationship with her. ↵

- Eberts, Griffith Park, p29. ↵