15 Reform & Redeem?

MARCH 1904 to OCTOBER 1911

“From personal experience… I am forced to the conclusion that the discipline of the average prison hardens, degrades and is a perpetual exhibition of cruel, arbitrary power… a prisoner can never be reformed by being wronged.”

—Grif speaking about prison reform during a lecture at one of his many West Coast stops from 1907 to 1909

Grif wasn’t immediately sent to San Quentin. An appeal to the California Supreme Court kept him in the Los Angeles County jail for 13 months, during which time he managed his business affairs but also suffered humiliations and one measure of legal satisfaction.

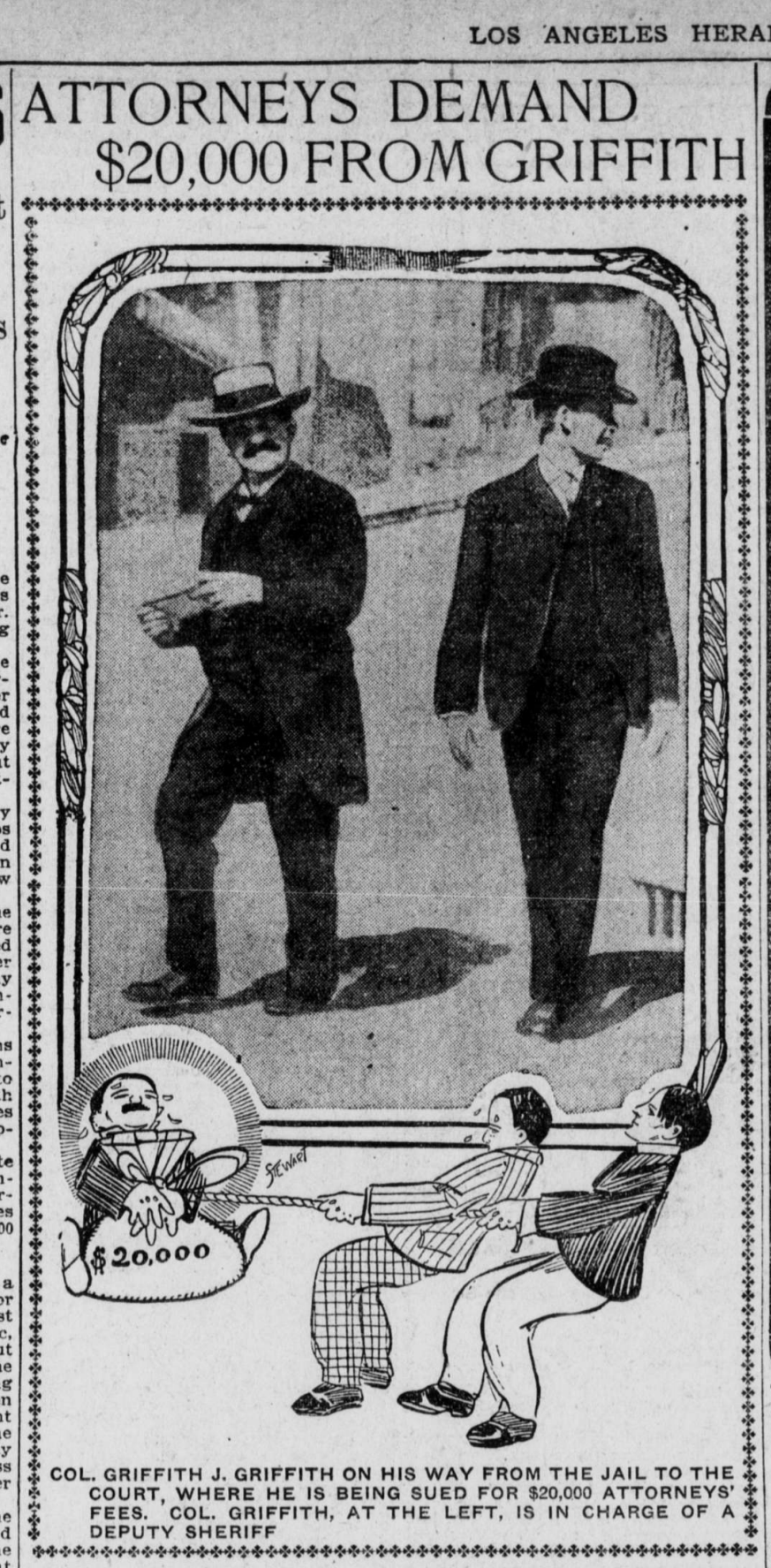

To start with, the day after he was sentenced Grif was sued by the two lawyers who had represented him in the divorce and property dealings as well as in the preliminary hearing before the criminal trial. They alleged Grif owed them $20,000 in unpaid legal fees and the lawsuit would entertain readers, while embarrassing Grif, for weeks.

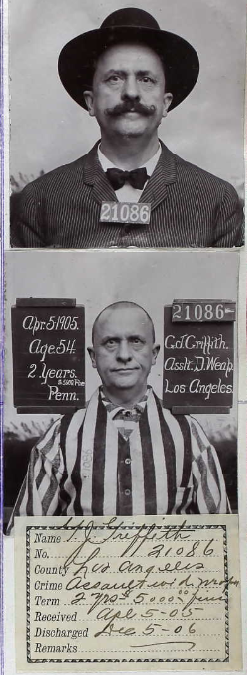

Grif also failed to secure bail, first with the judge who sentenced him and then with California’s Supreme Court. A March 1904 visit to the court in San Francisco, escorted by a sheriff, did not convince the justices that Grif’s health was declining — especially when Los Angeles’ prosecutor provided four doctors who swore that Grif was healthy. He had even lost 20 pounds, so instead of the portly Grif he now weighed a reasonable 157 pounds for his 5’6” frame.[1]

Then, on April 14, the city’s Board of Park Commissioners, while legally unable to change the name of Griffith Park, approved a motion to name its highest peak Mount Hollywood, not Griffith Peak as it had come to be known in 1902.

Week to week, it seemed, the family name, so carefully curated over the previous decade, continued being devalued. During all this, and even during the trial, nothing had been reported about the youngest Griffith — 15-year-old Vandel Mowry Griffith. As per the divorce terms, the sole son and heir was in his mother’s custody. The two lived at the Alvarado Hotel downtown, with Van attending high school nearby.

But on May 5, 1904, two months after Grif’s conviction, Van disappeared and was now center stage in the Griffith tragedy. Newspapers reported that Van had told his mother he was off to school but never made it, raising fears he ran away to start a new life or, worse, had been kidnapped. Tina was “on the verge of collapse” and “confined to a bed”, the Herald stated, while Grif, unable to do anything from jail, was “greatly perturbed”. Grif said he didn’t think Van would leave “of his own volition”. Another news report had Tina telling one visitor that she had enemies capable of kidnapping her son.

The disappearance certainly created sympathy for Tina and even Grif. It was only five days later that Van was found in San Francisco working as a messenger boy under an assumed name. It became clear that Van had had enough of his family’s tragedy and wanted to start over on his own — and at just 15 years of age. Once found, however, Van willingly returned to Los Angeles and over time would become a fixture in the city much as Grif had been in his heyday — first as an aviation pioneer, then a reporter, and finally as Griffith Park’s biggest booster after his father.

From Legal Friends to Enemies

Grif, meanwhile, saw the lawsuit by his former lawyers meander through the court system. Grif’s current legal team, again led by Earl Rogers, insisted he was not wealthy and that the accusers, Charles Silent and John Works, were trying to gouge Grif. The Times showed no sympathy, portraying Grif as a bitter and self-centered convict who “waxes smug and happy” from a comfortable county jail cell. A July 28 report was particularly telling. “Periodically, Col. G. J. Griffith comes out of his jail cell, in which he meditates upon the inadvisability of shooting one’s wife and rips his previous attorney, Charles Silent, Esq., up the back. The latest ripping was done last night. It was almost a massacre.”

That “massacre” was Grif stating he “would rather meet a highway robber” than have Silent as his lawyer. Grif also came across as blaming Silent for his criminal conviction. “Silent got up this insanity plea because I couldn’t remember some of the details of the unfortunate accident,” he stated, “but if I get a new trial I could tell my story to that same jury and – whoff. Like that I would be acquitted.”

If Grif came across as delusional and/or pathetic, he didn’t help his case with the press by adding that if he got a new trial and was acquitted, “I will forget all the mean and unkind things you newspaper boys have written about me.”

A jury eventually awarded the lawyers just $500 more than the $4,000 Grif had already paid them. But it was still Grif, not the lawyers, who felt the poison pen during the case. When the lawsuit trial started on October 11, the Times introduced Grif as “the little dark man with sad eyes and subdued manner” who “used to go swaggering round Los Angeles as though he owned the whole town and had a mortgage on the ocean.” In a front page article on October 22, the Times used the verdict to summarize Grif’s saga, starting with all the expenses he had accumulated since shooting his wife. “Were the unprofitable ledger of this man’s life spread open, one might read on a page these entries, traced in blood:” — and with that began a long list that totaled $78,780.

The Times also noted the injustice that even with those expenses, the value of Grif’s properties had increased 50% in that same time. And it reflected on the first days after the shooting, describing Silent and Works as loyal attorneys while Griffith refused to believe he would ever be tried, “true to the pompous promptings of his supremely egotistical nature”.

Supreme Dead-End and Off to San Quentin

As the lawsuit wound down (an appeal by Silent and Works left the outcome in limbo for months), the California Supreme Court decision on Grif’s appeal was nearing. It came on March 1, 1905, and it was decisive. Not only was the appeal denied, the justices came down hard on Grif, calling his actions “brutal and unpardonable”, and essentially agreeing with the press and public that he got off easy. They denied Grif’s appeal and pondered why the jurors acted as they did. “The jury seems to have concluded that he was legally sane and responsible for his actions, but seems further to have entertained a reasonable doubt as to whether or not he actually and deliberately did the shooting,” the justices wrote. “It gave him the benefit of the doubt.”

View the entire California Supreme Court ruling in People v. Griffith

If it was any consolation to the public, Grif’s extra prison time in Los Angeles, nearly 13 months, would not count towards his San Quentin time of two years.

An attempt to seek a retrial also failed, and on March 30 Grif had no options left but to leave the county jail for San Quentin. Still, he was in an “uncommonly happy frame of mind for a man in his position,” the Herald recounted, one of a few dailies whose reporters visited him to seek comment. “After patiently waiting over a year behind prison bars and bolts I still possess my ambition,” he said of his long appeal process. “I shall aim to bear my future troubles as I have my past. This long confinement may yet prove to be a blessing in disguise. Who knows?”

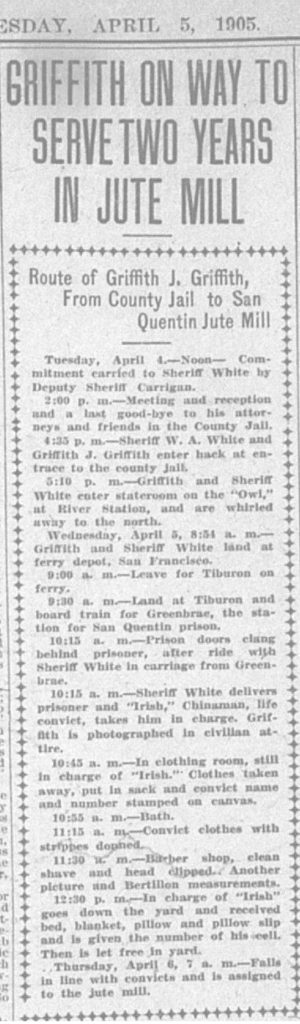

And so, on April 4 Grif left Los Angeles for the state penitentiary. Escorted by a deputy sheriff, Grif was sent on the overnight Owl express for the train trip upstate and was allowed to pay for a private drawing room in a sleeper — his last bit of luxury for a spell. The Examiner relished describing every movement, listing developments by time stamps and noting that Van visited his father before others to say his farewell in private.

Grif later recalled how despair gripped him at first as he left Los Angeles. “I shut my eyes, but could not shut out the knowledge that we were passing through the long familiar streets, or that the crowds by which we hurried contained many who knew me well,” he wrote.[2] But then he started to reflect with a maturity brought on, perhaps, by his new reality. “As the (rail)cars pounded along through the desert, I composed myself and thought. Hour after hour I thought, steadily and hard; reviewing the past, sizing up the future.

“I had no regrets; I never have. The past had its merits and defects. So have all pasts. The only question worth considering was whether the failures could be turned into gains. The future was the thing, and again I grew hopeful. Two years, less the credits I certainly should earn, would quickly pass away … Whatever happened I must keep my self-control. If possible I must make hosts of friends, and I must not fall. I thought it all out in the long vigil of a sleepless night… I tried my best to discard ‘illusions, delusions and hallucinations’ — terms repeatedly used during my trial.”

He entered San Quentin on April 5, 1905. His prison survival strategy, he told his son in a Christmas letter, was to stay positive, not to seek favors due to his wealth, and do the work any prisoner would do. “I have not allowed my misfortune in any way to sour or embitter me against society or my fellow-men,” he wrote. “I aim also, in my conduct and actions, to make the officers and prisoners with whom I come in contact, better men”.

It wasn’t easy, he’d later recall, especially when his arrival as a millionaire prisoner made him enemies. “I put myself in a fighting attitude” when several inmates threw objects, but after an initial impulse to seek revenge he remembered “love is reflected in love” and asked himself, “What was the loving thing to do?” So he turned the other cheek, refusing to tell the warden who his attackers were, and earned their respect.[3]

In his first year as an inmate, he made jute bags alongside 800 other prisoners. Grif said he refused easier work offered by the warden, and even insisted on being moved from a single cell to a room holding 48 inmates so that he could get to better know his peers. He even took on the role of newsreader, spending two hours a night relating events to his cellmates.

Back to Los Angeles With a Purpose

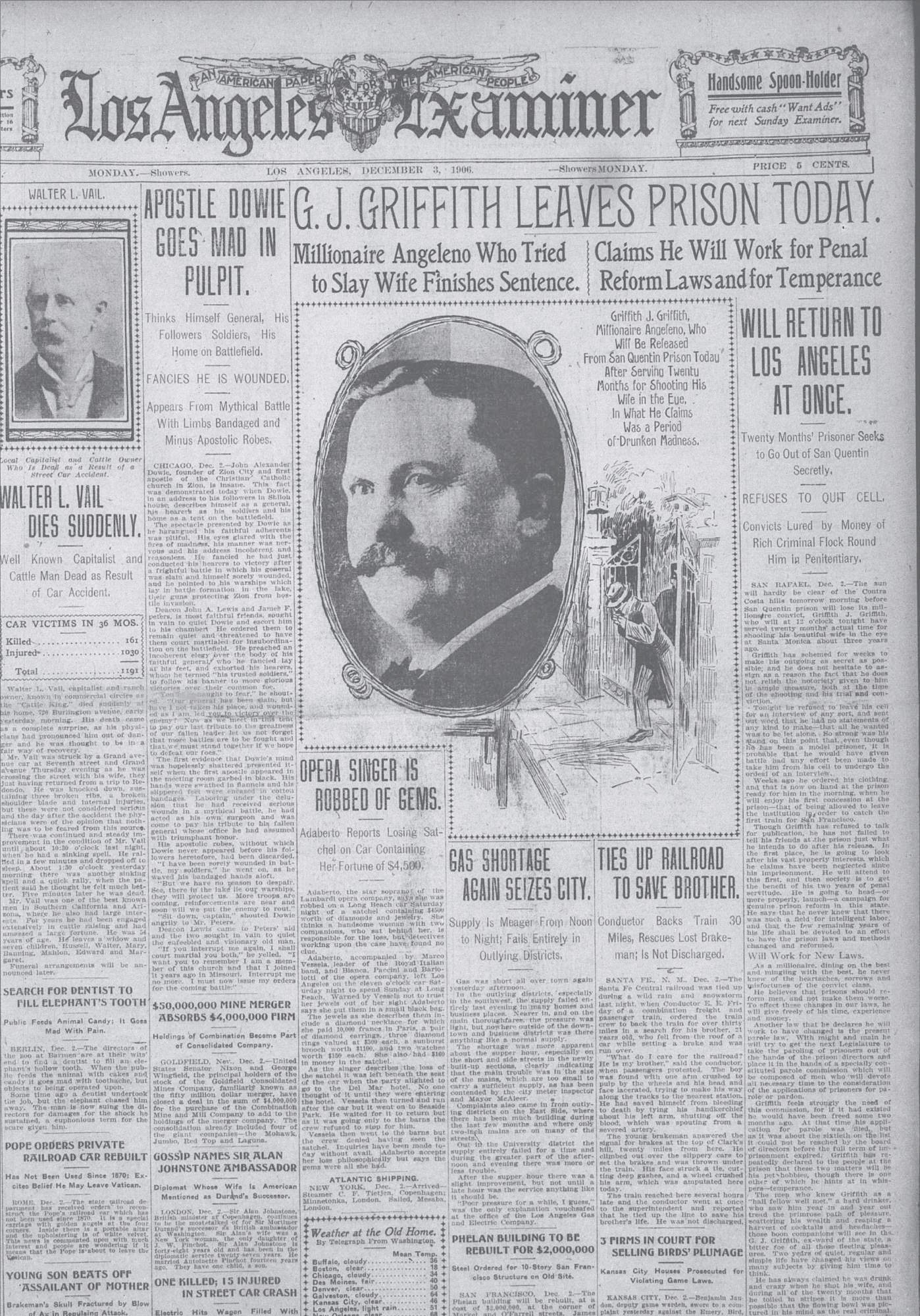

San Francisco’s 1906 earthquake, which destroyed 80% of the city, delayed Grif’s parole hearings for two months but when his time came his sentence was reduced by four months due to good conduct. That meant Grif would be freed in December 1906, and the Times wasted no time mocking him. “He is about to change his occupation from that of skilled laundry girl,” it noted in a cheap jibe at prison chores, “to that of capitalist” — a reference to the fact that the nearly 800 acres of the former Rancho Los Feliz that he still owned had appreciated in his absence to $1,000 per acre.

The story was impossible to miss being at the top of the Times local section on Sunday November 25 — and with a photo of Grif to boot. A few sentences described Grif as the “handsome and pompous” man who initially made money having been “tipped off” by mining associates and who later married into the Mesmer family wealth. Once married, Grif was “a frequent tourist down the ‘cocktail route’,” a reminder of the drinking habits all too-well documented in his trial.

A Times editorial on December 6 titled “Give Him a Chance” did urge readers to not judge prematurely. The Graphic, a society weekly, also urged readers to “Let Him Be”. But given the earlier front-page Times coverage, as well as how Grif’s acquaintances had portrayed him during his trial, one would have expected Grif to exit prison an angry man who would move to another town or at least keep a low profile, a shell of his former self. The Examiner, for example, ventured that it is “not believed that he will make his permanent home” in Los Angeles. The Jonathan Club, for one, had rules that expelled any members deemed to have acted inappropriately. It seemed unlikely that Grif, even with the ego he was known for, would try to resume his pre-prison life.

But Grif surprised his detractors, returning on December 10 to his beloved Los Angeles and to the public spotlight with a new social cause: reforming the prison system he had experienced first hand. That reform spirit had always been part of the Grif known by Angelenos – from taking on the Southern Pacific railroad with a “free” harbor, to kicking out political party bosses in favor of honest elections and good government. But now he was taking on a cause that was a social taboo: prison life was not something to talk about in polite company.

Other men of means would have tried to bury a prison experience as fast as possible. But not Grif, he turned it into a personal challenge. He was extending the Progressive Era mindset of cleaning up politics to cleaning up an institution that few wanted to acknowledge. And like many Progressive-era reformers, he believed in “environmental determinism” — that one’s surroundings often determine one’s fate. So a poor, young lad taught to steal, for example, is not so much a criminal as a victim.

Odd Reform Bedfellows

Over the next three years, Grif visited prisons across the country and even Mexico, made speeches and political allies, founded and funded a Prison Reform League, and published Crime And Criminals, a 320-page opus based on first-hand accounts of prison life, especially his own.

As most of his peers were not ready to go where he was suggesting, Grif instead found friends in what for him were unusual places. His three most trusted reform allies were the head of the Prohibition Party, an anarchist and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union – yes, all three ironic choices given Grif’s history as a boozy capitalist who shot his wife.

Grif spent much of 1907-1908 traveling 15,000 miles to visit prisons, interview other ex-cons and study reform. Then he added a lecture tour focused on the West Coast and which included Sacramento, knowing that any reform in California had to pass through its capital. Grif’s time there included personally lobbying state lawmakers.

His criminal celebrity status made for packed houses and an appreciation that this reformer knew what he was talking about. This was not the egotistical, pre-prison Grif speaking, but a man extremely sensitive to the hardships of others. The core of his standard speech included this passage:

“From personal experience, observation and knowledge I am forced to the conclusion that the discipline of the average prison hardens, degrades and is a perpetual exhibition of cruel, arbitrary power.

“Treatment that puts an impassable gulf between prisoner and society will never make a convict better. Men in prison, much like those out of prison, can be made better and they can be made worse, according to their treatment, environments and opportunities.

“Man is not a commodity. He is not a compound of mathematical quantities or chemical gases. He has a heart and a brain, and between these spring a thousand needs and emotions. He has the instinct of love. He is conquered by justice and any plan for the measurement of man which leaves out justice will and must be a failure.

“I wish I could make it so convincingly clear that the civilized world could fully realize it, that a prisoner can never be reformed by being wronged.”[4]

He would then elaborate, often using his own experience as an example. Some inmates are naturally evil, he would admit, “but the great majority are not bad men. The average prisoner is not so radically wicked as he is pitifully weak. Many are accidental and unwilling victims of circumstances over which they had no control”.

Grif’s focus was on California, which lagged many states in terms of reforms like creating a parole board and training prison officers to rehabilitate, not crush, convicts. The current philosophy, he would tell his audience, is epitomized by the words over the gateway into San Quentin: “He who enters here leaves all hope behind”.

“Modern methods and California have always been strangers,” he would add, “as is most evident in that corral of horrors known as San Quentin”.

The warden constantly told his 1,600 inmates that they were “sent there to be punished” — once he even ordered every photo and personal item burned in a huge bonfire. Most inmates had such items from family, Grif noted, showing that they could love and be loved.

“Instruments of torture” included the straight-jacket. Inmates were often tied up for hours on the whim of a given guard. Once, a new convict who resisted was dragged away and never seen again, Grif stated. Another came out with his arms and shoulders maimed after 140 hours “squeezed” by the jacket.

A dungeon with a dozen cells was just below the sleeping bunks, a reminder to all to avoid that place. Heavy chains secured prisoners in the dark for weeks at a time. “Hundreds of times I heard pitiful cries for mercy,” Grif said, “followed by human moans and groans.”

Even the prison’s doctors were “heartless and cruel”. One had a cure-all cathartic known as the “bombshell”; another treated every sickness by flushing a gallon of water down one’s throat with a rubber hose.

Particularly frustrating, Grif noted, is that San Quentin had become “a school for crime, where the youth from 14 to 21 daily and constantly come in contact with hardened and degenerate criminals.” Most cells hold dozens of prisoners so “when they are thus herded together, what is there to prevent the expert criminal from conducting post-graduate courses in crime?”

And even when a prisoner’s time is up, Grif explained, he, or she, leaves San Quentin “in a sad and pitiable condition to face the world. Health shattered, courage gone, he has a shifty bearing, a bitter distrust of fellowmen, and the loss of ambition to win back a place in life.” To make matters worse, detectives were often watching those ex-cons, waiting to cash in on bonuses for re-arrests.

“If but half the money and energy used in prosecuting crime and persecuting people was applied to finding employment for idle men,” Grif told his audience, “conditions would greatly improve.”

Seeking Reform and Redemption

It looked like this reform path was also becoming one of redemption. The Times, just two months after skewering Grif and his imminent return to Los Angeles, noted on its front page of February 16, 1907, that Grif had testified before state lawmakers, arguing the existing parole board was too slow and that hiring more staff was needed to provide a fair process. The Graphic trumpeted “Griffith’s Good Idea” and its editor vouched: “I have seen Griffith since he has been out. He seems to have had a deal of the pose and conceit knocked out of him; and he hasn’t been drinking.” The Sacramento Bee highlighted an opinion piece by Grif with the subtitle: “California Far Behind Other States in Up-to-Date Methods”.

The Times later went even further, on October 6 giving Grif most of a page to explain his views on prison and describe his own barbaric experience. The article was prefaced with a note from “The Editor of the Times” that described Grif as “apparently chastened and reformed” after having been “unfortunate enough to fall into evil ways”.

While not endorsing his ideas, the editor praised Grif for writing “thoughtfully and with sincerity, and enlightened by experience.” It seemed Grif was back in good standing with the Times — indeed, subsequent Times articles restored his title of distinction. Grif was again “Col. Griffith” to its readers.

And the Graphic, a year after welcoming Grif back to polite society, recalled on February 1, 1908, that while the pre-prison Grif was “about as offensive a personality as could be encountered”, his post-prison behavior had been “irreproachable” and he was “on the threshold of the most useful and creditable part of his life” given his prison reform efforts.

Two months later, Grif was invited to speak in Los Angeles by Mayor Arthur Harper and several judges. The Times trumpeted the April 1908 invite for the public to “hear the thrilling story of the man who served his sentence and now desires to spend his life endeavoring to better the conditions of other men under like circumstances.”

Not to be outdone, the Herald followed up with its own enthusiastic coverage. “Wealthy Los Angeles Pioneer Engaged in Philanthropic Work” read the October 19 headline above a two-column portrait of Grif. After briefly extolling the reach of Grif’s work, the Herald re-published a long piece from Maine’s Bangor Daily Commercial — not a source with first-hand knowledge of Grif, but that didn’t stop the superlatives. Griffith J. Griffith, it stated with confidence 3,000 miles away, is “the Californian who occupies the largest place in the public eye of his state just now … millionaire, philanthropist, criminal, convict and reformer, considered one of Los Angeles’ greatest benefactors”.

The Herald then tacked on a short article by an unnamed, old acquaintance of Grif. It read in part: “Ever since 1873, there has not been a great public movement in this part of the state for its betterment up to the day of his misfortune, but that Col. Griffith was one of the wheelhorses in all such events.” It was inaccurate in as much as Grif wasn’t even living in Los Angeles until 1882, but Grif must have appreciated the platitude nonetheless.

With this momentum in his favor, Grif in April 1909 launched the Prison Reform League, its chief goals to abolish the death penalty, reform federal prison statutes and improve the parole system. The idea was to expand nationwide and Grif recruited a man with national experience as a co-founder: Chicago-based Eugene Chafin, head of the Prohibition Party and unsuccessful (1.8% of the vote) candidate for president in 1908. The teetotaler teaming up with the infamous millionaire drunk who nearly killed his wife — now that was an odd couple.

San Quentin as Grif Knew It

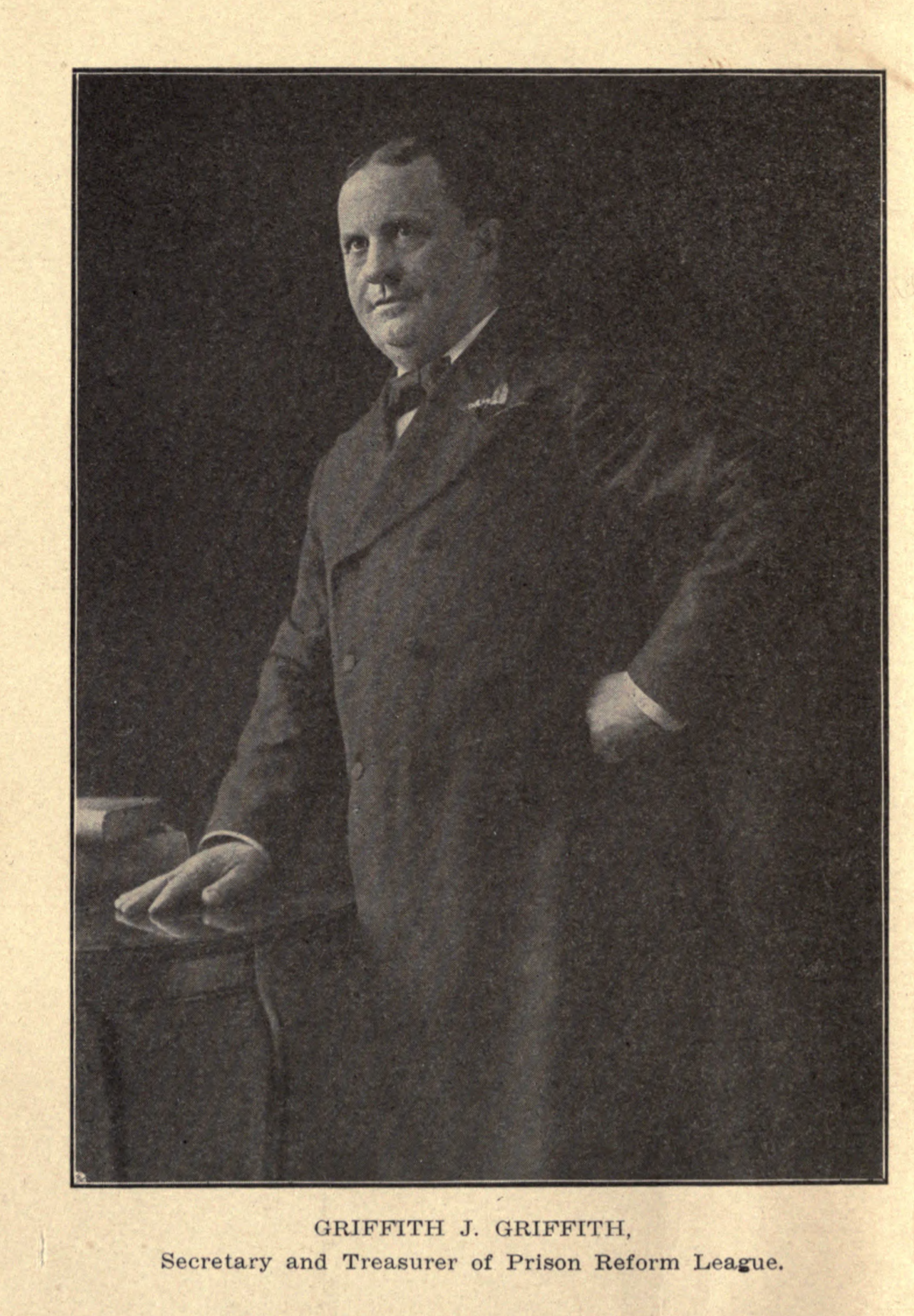

Largely funded by Grif, the league in 1910 published Crime And Criminals. The opening pages present Grif as Prison Reform League secretary and treasurer, and include a full-page photo portrait — not of a man in prison stripes but the pre-prison Grif, slicked-back hair, dark suit and bow-tie.

The New York Times and Los Angeles Times gave it positive reviews. Many thought Grif had written most of it, but it was later revealed that the majority was written by one William C. Owen, a well-known anarchist and best friend of Emma Goldman — “the high priestess of anarchy”, as The Los Angeles Times called her. Capitalist Grif and anarchist Owen seemed to get along fine, at least at first, and Owen even used Grif’s office as his personal mailing address.[5] Owen would go on to write prison reform columns for the Herald and remained in Los Angeles until 1916 when, sought on sedition and inciting murder charges, he fled to Canada and then to his native Great Britain.

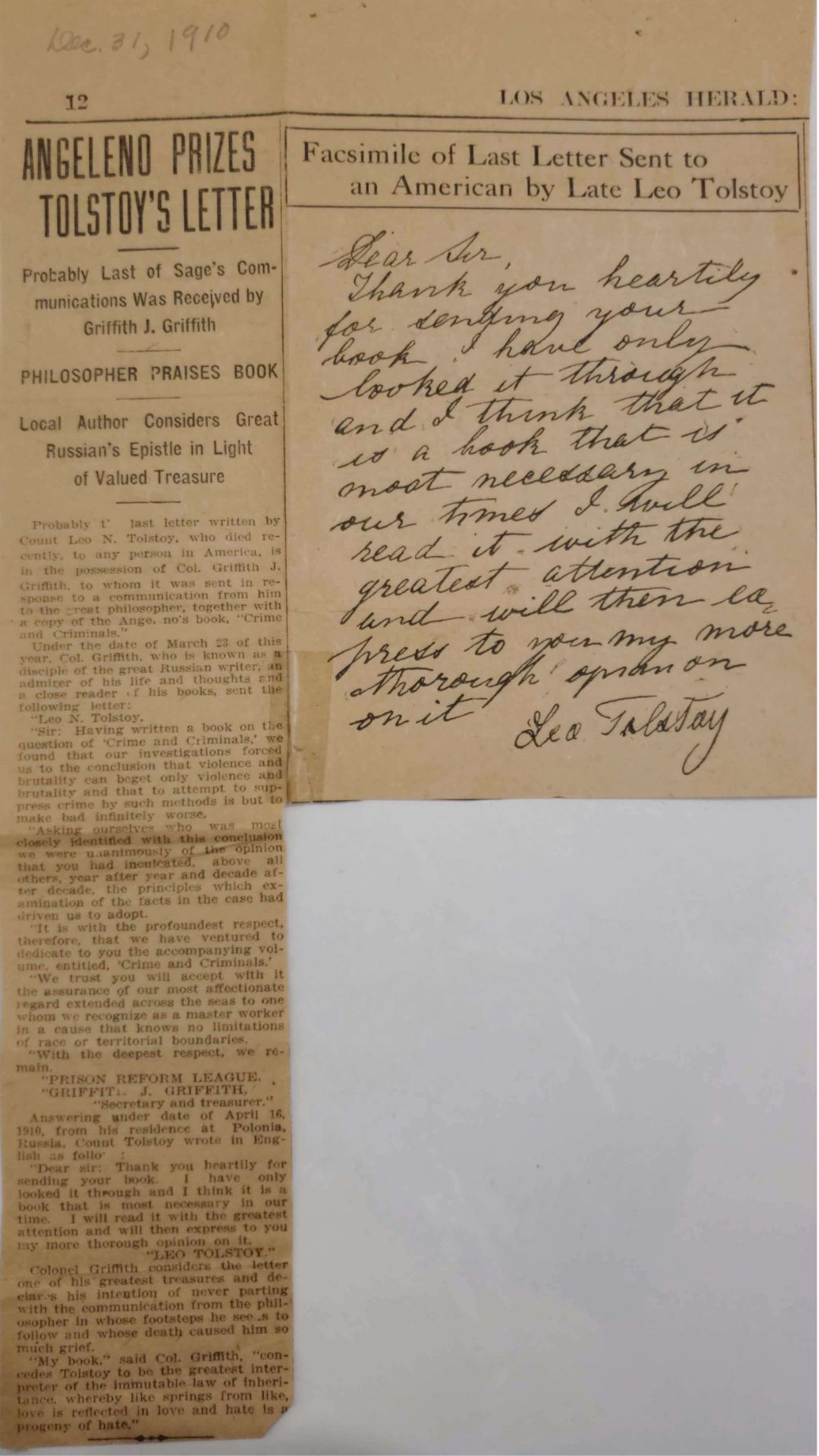

Grif and Owen shared a belief that cruel punishment would only beget more cruelty. In Crime And Criminals, they emphasized that by dedicating the book to a novelist/anarchist who tackled social injustices and would help inspire the Russian Revolution. “To Leo N. Tolstoy, the world’s great interpreter of the immutable law of inheritance – whereby like springs from like, love begetting love and hate a progeny of hate – this book is dedicated, with profound respect”. Tolstoy was sent a copy and wrote back thanking Grif — a handwritten letter that Grif treasured and shared with the Herald. The news clipping, which included a facsimile of the letter, was kept by Grif the rest of his life and was eventually archived with other family documents.

Grif did have a major role in the book, not only paying for it but writing a section that pulled together his speeches and newspaper articles. In Chapter 4, “San Quentin as I Knew It”, Grif shared the humiliations that most men of his status would have kept hidden. Prison conditions would have never been on his mind, he admitted, had he not been “forced to think” about it by being “brought face to face with such a mass of human stupidity.”

Of his first day, he wrote: “My rough undergarments irritated me horribly; the fetid prison air, heavy with the taint of humanity, weighed on my nostrils; the cell, of steel from floor to ceiling, chilled me through and through.”

The system was set up to dehumanize inmates. For showers, 300 men stood naked waiting in line outside for their turn, and had to use jute sacks to dry off if they didn’t possess a towel. Wash day often meant wearing wet clothes that hadn’t fully dried. Rheumatism was rampant as was tuberculosis, and yet sick inmates were rarely separated to minimize the spread of disease.

The humiliations included dealing with sewage. “Each man brought out his pail containing the slops of the preceding twenty-four hours and emptied it into a general receptacle. As there were hundreds of men to each receptacle, and as the latter became clogged from time to time, the process was disgusting.”

The food was mostly “execrable … The meat was served largely in a form known as ‘deep water stew’, which was admirably calculated to conceal its tainted condition. The mouldy beans were often too rank for cooking and were hauled in large quantities to the hog ranch… The potatoes were small, watery and full of worm holes.”

How could that system return a prisoner to society, Grif asked. “Authorities doing their best to undermine his constitution and cripple him with disease adds materially to the shame of the situation.”

Near where Grif and others slept were “torture dungeons” that produced “groans and cries” at night. Chains restrained those being punished and Grif said he knew of one prisoner who spent 59 straight days tied up.

Grif elaborated on the straight-jacket torture. “If, through carelessness or vindictiveness … the jacket is laced too closely, or if the confinement is continued any great length of time, permanent deformity, paralysis or serious internal derangement will result. The natural excretions of the body are much affected and the circulation of the blood is impeded, which, as any doctor will tell you, causes great anguish and often excruciating pains in the head.”

Two men were so injured that when they were finally paroled neither could use his arms, making it that much harder to return to civilian life. One had been 14 hours in a jacket and was now essentially a cripple, Grif wrote.

State law banned the use beyond six hours straight, but guards would simply unstrap the prisoner for a few minutes, and then for most it was back in the jacket. “This intermittent punishment was more painful than the old plan,” Grif noted, and shows how the system was still wicked even with a ban. “If public opinion drives one form of barbarity out another will immediately take its place,” he preached, unless prison officers are properly trained.

Grif also described sex offenders preying on young convicts, as well as old convicts talking about a prison system long barbaric. From the latter, he stated, “I obtained a great insight into the life of the habitual criminal, (and) the causes that make him what he is”.

Better than Carnegie or Rockefeller?

Grif’s reform push was not a complete success — his efforts to secure three bills passed both state congressional houses unanimously, but Gov. James Gillett failed to sign any into law. Still, combined with the praise Grif received and tangible changes like new San Quentin and Folsom wardens, he probably felt he had done as much as he could, especially in such a short time.

The Prison Reform League claimed 4,000 signed supporters in California and many in Illinois but never expanded as hoped. Grif did send out weekly opinion pieces to 300 newspapers including the Sacramento Bee, which reached lawmakers in California’s capital.

Among his biggest supporters was the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, ironic given his own domestic history. The union was instrumental in lobbying the state to improve the conditions for female prisoners. Crime And Criminals included a chapter written by a female ex-con and Grif himself wrote that from San Quentin’s female ward came reports of “cruelty and debauchery that … are too revolting for me to relate”.

The parole system reformed slowly, over decades, but credit “belonged in great part to Griffith,” a prison historian would later write.[6] Whereas in 1906, only 49 men were paroled in California, by 1908 it was 197. Even more were paroled in 1910 when the prison board leadership changed. Grif was particularly proud of his lobbying, and even kept a 1910 Herald clipping written by an ex-con who was certain that what Grif accomplished “outbalances anything Carnegie or Rockefeller ever did for their fellowmen.”

Of course, Grif wasn’t the only prison reformer. But he had a celebrity pulpit, especially in California given his recent criminal history. And he wasn’t ashamed to use it to preach that most people are inherently good, not evil, and that a person led to crime usually takes that route due to circumstances beyond his or her control.

That enlightened look at human nature extended to immigrants, who at the turn of the 20th Century were increasingly seen as troublemakers, especially when it came to crime. Writing in the December 10, 1910, issue of the journal The Business Philosopher, Grif countered that the root of the problem was that “we ourselves do not give the immigrant half a chance… He finds himself face to face with expensive cities, cold commercialism and political corruption.”[7]

His reform belief was so strong that it allowed for those strange bedfellows of Owen, Chafin and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. In May 1910 Grif even visited Owen’s friend Emma Goldman, by that time a widely known international anarchist who had been arrested repeatedly. [8]Writing in the magazine Mother Earth, she had earlier praised Crime And Criminals as “a book every social student ought to read – the most scathing indictment against our entire penal system ever published.”[9]

Another unexpected partner was Abe Ruef, a former San Francisco mayor who landed in San Quentin in 1911 for kickbacks and bribery. Ruef, too, saw prison as counterproductive and proposed a work program for ex-cons. Grif immediately pledged $1,000 to help the cause which, alas, never got off the ground.[10]

On the national stage, Grif the prison reformer peaked in October 1911, when he addressed the American Prison Association convention in Oklahoma. The gathering of wardens and other prison officials already reflected a more humane system, but Grif pushed them to lobby for an end to the death penalty. “We are calling on a whole nation to revise its thinking,” he acknowledged.[11]

That was Grif’s last major public appearance on behalf of the Prison Reform League. Perhaps he felt he had done as much as he could, and received enough accolades to qualify for redemption at home. In any case, Grif was already pivoting back to his earlier life and passions. Grif’s next campaign was foretold in late 1910, when the Prison Reform League published its second, and only other, book. Titled Parks, Boulevards and Playgrounds it did mention the value of parks in reducing crime by creating safe, healthy cities. But it was more a statement to Los Angeles, and a reflection of Grif’s renewed focus, that Griffith Park was still not being used to its full potential.

- San Francisco Call, March 19, 1904. ↵

- Prison Reform League, Crime And Criminals, pp55-56. ↵

- Ibid, pp60-61. ↵

- Griffith's standard reform lecture is reproduced in a Crime And Criminals appendix, pp285-312, and cited throughout this chapter. ↵

- Herald, December 28, 1909. ↵

- Shelley Bookspan, A Germ of Goodness, p66. ↵

- The Business Philosopher, December 10, 1920, pp853-854. ↵

- The Emma Goldman Papers Project at UC Berkeley documented a visit between Grif and Goldman on May 20, 1910. Specifics were not provided. ↵

- Mother Earth, June 1910, pp127-128. ↵

- Times, August 12, 1911. ↵

- American Prison Association, Proceedings of the Annual Congress, 1911, pp243-246. ↵