5 Stumbling into the Gilded Age

1884 to 1887

__________________

“Fortune smiles brightly on this her favorite son, and all that he touches turns to gold. His possessions are in California, in Mexico, and in many other places. They represent broad acres, and rich mines, flocks, herds, and wealth in Protean forms, and Plutonic magnitudes.”

— The Los Angeles Herald, describing the newlywed Grif on January 28, 1887

Grif quickly used his water wealth to pivot from gentleman rancher to dapper city capitalist. America was living what Mark Twain dubbed the Gilded Age, an era of unbridled capitalism exemplified by the rail tycoons. Grif, for his part, was trying to fashion his own Gilded Age. Flush with cash from the water sale, Grif went into the money lending business, then diversified into ostriches and eventually tried to rent out most of the rancho. It didn’t always work out well.

He also moved into a hotel suite downtown and at some point assumed the title of “colonel”, which in those days offered some social cache — even though his only military service was a brief stint with the California National Guard, where he achieved the lower rank of major in 1884.

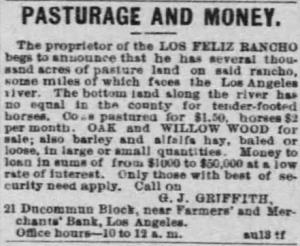

The Times first referred to “Colonel Griffith” on August 13, 1885, when it directed readers to select ads in that day’s edition.[1] Taken out by Grif, the ad (see below) was short, to the point and came across as if Grif had tired of running the rancho or, worse, was not able to make it work financially. “The proprietor of the LOS FELIZ RANCHO,” the ad began, “begs to announce that he has several thousand acres” to pasture cattle at $1.50 a head per month and horses at $2. Oak and willow wood were also for sale, as well as hay. The last sentence presented his newest business venture: “Money to loan in sums from $1,000 to $50,000”. Interested parties were to visit Grif at his new downtown office on Main Street.

Grif even made it onto the Times’ front page three days later, though not as he would have wished. A catchy headline, “THE LOGIC OF THE FIST”, drew readers into a brawl between Grif and a stonemason who had worked on the rancho and appeared at his downtown office. “There was a quarrel about payments, and words swelled to blows,” the Times reported on the bottom right of Page 1. “Whichever began hostilities, the other ably seconded the motion, and they had a very cordial free fight in the little office and in the hall at the head of the stairs.” Grif’s chief weapon was an inkstand that landed on the stonemason’s head, and both “wrenched out two of the stair-bannisters and used them for clubs”. By the time police arrived to arrest both bloodied men, a crowd had gathered to see that Grif “got much the worst of the encounter. His left eye was in a horrible condition, and his face much battered.”

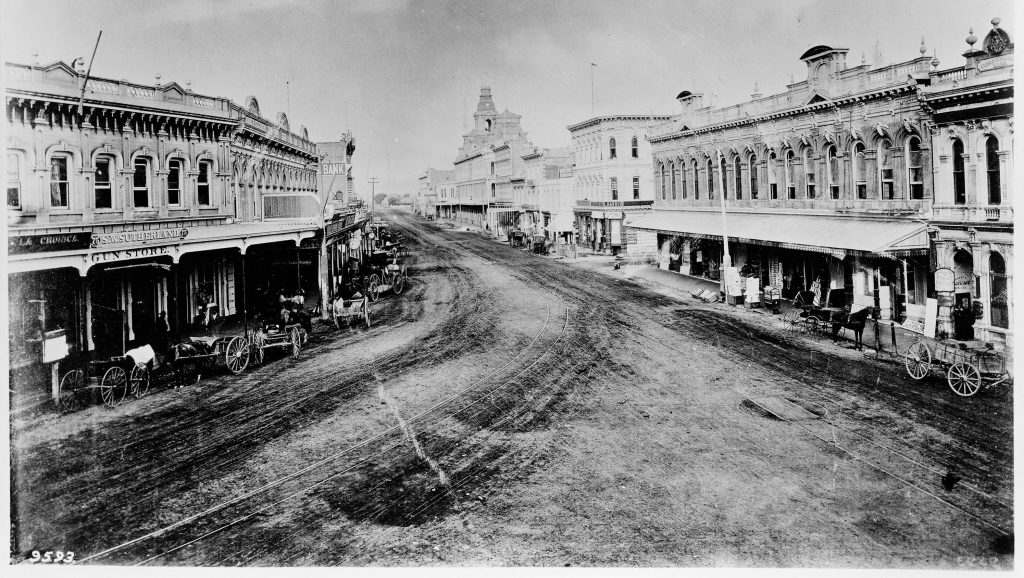

Los Angeles was not yet the sophisticated city its boosters wanted, so Grif’s skirmish could be overlooked as a throwback to the Wild West. The city’s elite was much more focused on how to move forward. Associations to promote manufacturing and to attract white, Yankee immigrants were started in 1885, and voters helped too. They surprised even boosters when, by a 4-to-1 margin, they approved $245,000 in bonds to repair streets, bridges and the city sewage system. A few months later they backed high fees on saloons as a way to keep them from sprouting across the city.

Other improvements included a paid fire department with 300 men that replaced volunteers. But the most excitement centered around the revolution in transportation. Horses, and the agonizing stagecoach trips they provided, were almost a thing of the past as far as long-distance travel was concerned. Within a decade of the Southern Pacific railway arriving in 1876, investors had built out 200 miles of track for electric and cable railways across Los Angeles.[2] Then, in November 1885, the Santa Fe railway rolled into town, starting a fare war with the Southern Pacific that led to tens of thousands more visitors — many of whom became property speculators, and some of whom became residents. Over the next 30 years, the world would be transformed further, first by automobiles, then by aircraft.

“Prince of Wales”

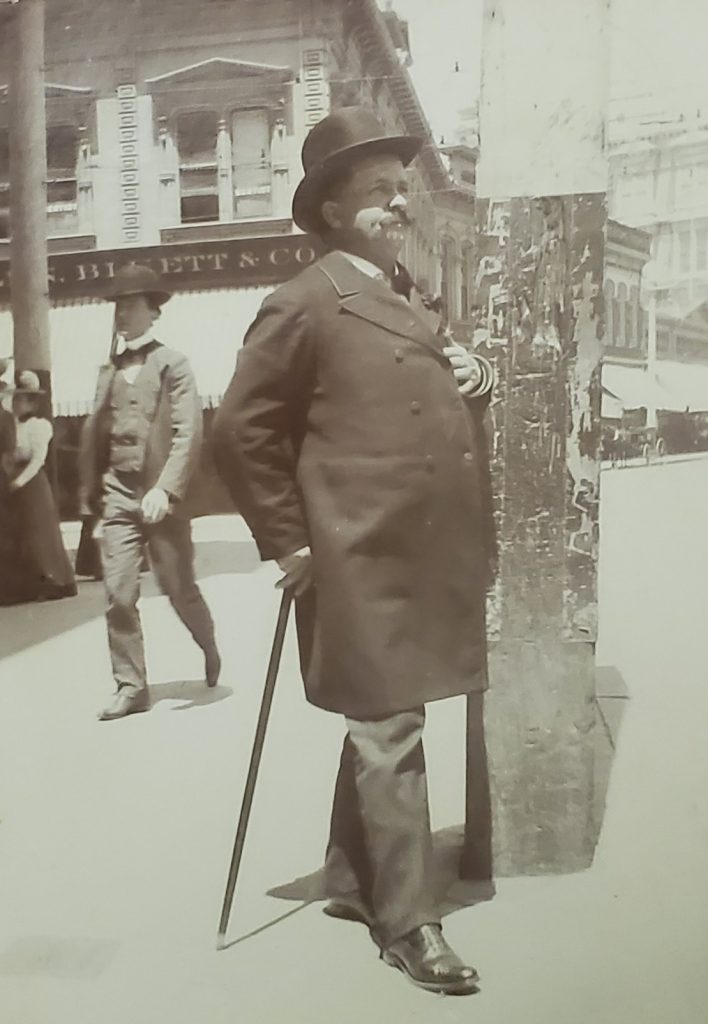

Los Angeles was certainly feeling and looking more sophisticated. Grif also started to dress the part — no longer rough riding in his handsome bay of horses, he walked about town dressed as a gentleman dandy. The Herald had started referring to “Col. Griffith” in June 1886, while the Times did so on and off until 1898, when Grif’s status was greatly elevated by several profiles and “Colonel Griffith” became routine.

It should be said that many a self-made man in those days picked up honorifics along the way. But attaching “colonel” to his name probably rubbed some people the wrong way since how Grif acquired the title was always a mystery. “The Prince of Wales” was how Horace Bell mockingly referred to Grif from his perch as editor at the weekly Porcupine. “When this grand personage was seen on our streets with his long coat buttoned from top to bottom, head erect and eyes disdaining to look upon the earth, the humble Angelenos could hardly be blamed for mistaking him for royalty,” Bell wrote in his memoir.[3] “Shoulders thrown back, abdomen thrust more than correspondingly forward, knob-headed cane carried under the right arm and an immense chrysanthemum or dahlia in his buttonhole — a conqueror surely, we thought — a Highness in our midst incognito.”

From Horses to Ostriches

The urban Grif still had one foot in the rancho, and in early 1886 he announced himself as a horse breeder. In a front-page Herald ad, Grif said he had acquired “one of the largest trotting stallions on the Pacific Coast” and ran snippets of letters from trainers and even a judge commending the male’s pedigree. “I can afford to stand him for the first season in Los Angeles for the very low price of $30,” Grif wrote in his ad. “A limited number of good mares may be arranged for”.

Grif’s boldest attempt at diversifying came thanks to an ostrich breeder from South Africa. Charles Sketchley, quite possibly after seeing Grif’s “pasturage” ad, in mid-1885 approached him with a dream of a 300-acre ostrich amusement farm.[4] The exotic animals were such an attraction back then that crowds paid to ride them and watch them swallow oranges. Grif gladly leased Sketchley and two partners the land needed for their ostrich farm. The operators, for their part, not only charged admission but plucked ostrich feathers, which were fashionable hat accessories and could make each bird worth $400 — much more than an acre of land back then.

Sketchley, and possibly Grif as an early investor, also sought to break the ostrich feather monopoly held by a New York City cartel that paid poorly for feathers. The Times reported on October 13, 1885, that Sketchley “sent to Paris for an expert preparer of feathers” and would soon sell direct to hatmakers and consumers “at a price ridiculously small compared with what has ruled heretofore.”

Sketchley and Grif were even reported to have orchestrated a unique campaign against cruelty to birds of a certain feather. “Some of the ladies of this city have formed an association and agreed not to wear feather trimmings on their hats or dresses in order to prevent the killing of plumage birds,” the Herald reported. “It is supposed that Dr. Sketchley and Col. Griffith put up the job in order to elevate ostrich feathers, as ostriches don’t have to be killed to get the plumage.”[5]

The farm quickly grew with the arrival of 34 ostriches from South Africa. A restaurant and refreshment stand appeared, and soon the farm could even call itself a zoo thanks to other species of caged birds as well as “bears, deer, monkeys, panthers, wild cats, wolves, coyotes, rabbits, guinea pigs, etc.” — as per a flattering profile by the Times on January 19, 1887.

The ostrich farm eventually had its own rickety railway that made for a wild ride from downtown. One rider, who went as a boy with friends, recalled the “great thrill … the sudden jolts, what the boys saw and heard — and sometimes there was the evidence that an unfortunate sheep, horse or cow had met its fate in contact with the cow-catcher”, i.e., the metal apron on train engines used to deflect objects on the tracks.[6]

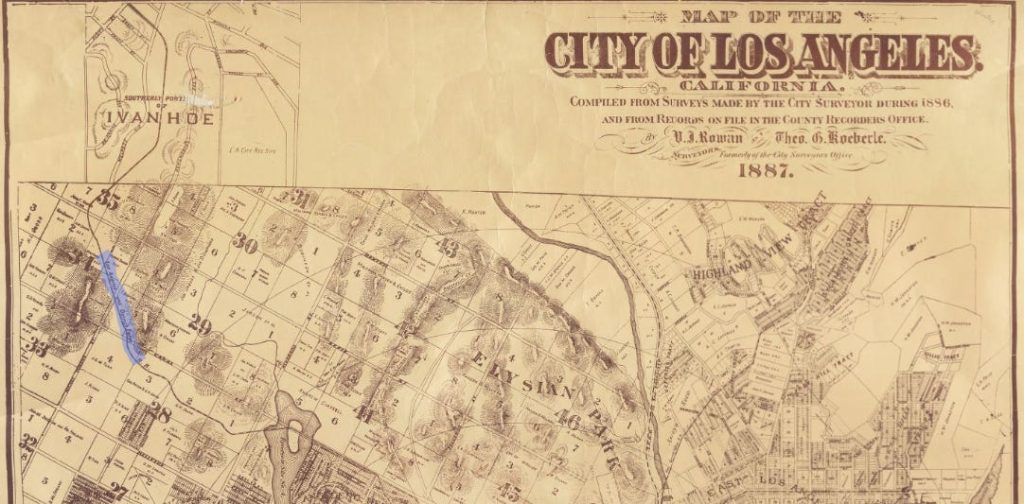

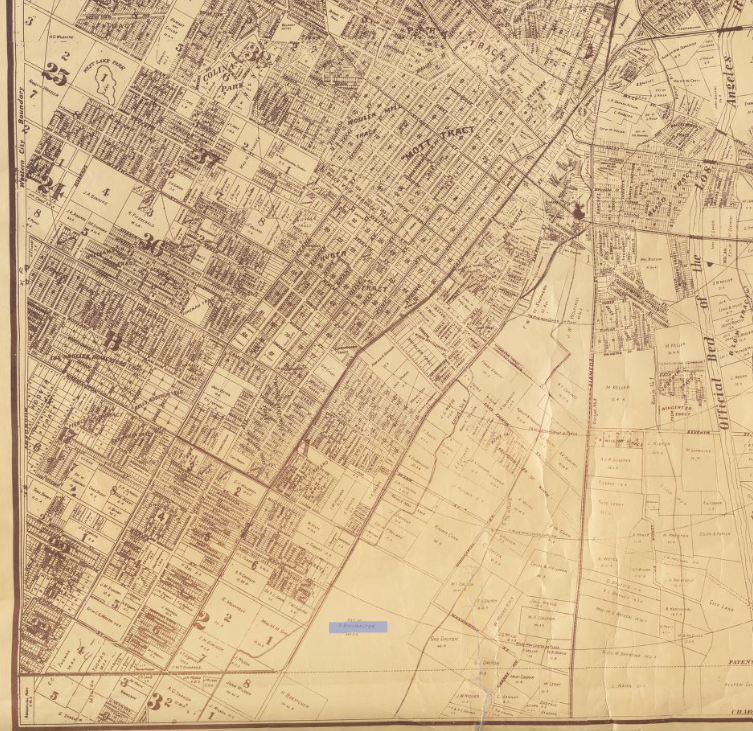

Grif chipped in $2,500 for the railway[7], and was its treasurer at the start. No doubt he was happy to invest since rail would make his land along the line more valuable. The Times, in announcing the proposed Ostrich Farm Railway on June 9, 1886, predicted that “this enterprise will open up a great quantity of desirable but hitherto inaccessible land, and is already hatching a boom in the northern part of the city.”

The farm went gangbusters for all of about a year, then things started going south, starting with a sex scandal. Late in 1886, Sketchley and a partner took legal action to remove a third partner for having “notoriously and scandalously debauched and had illicit intercourse” with two female employees on the premises.[8] The case was played out in the press and Grif must have been embarrassed by headlines like “An Infelicitous State of Things at Los Feliz”.

The farm struggled along for a couple more years[9], getting a boost at one point from an English investor who leased 300 acres and made his home there. That man would eventually try to kill Grif. More on that later, but suffice to say Grif survived.

Money and the Mesmers

Grif’s loan clients included Louis Mesmer, owner of the luxurious United States Hotel. The Mesmer family was established elite and very Catholic — Louis had even been entrusted by the city’s Catholic bishop to oversee fundraising for a new cathedral.

The two became friends and, as Grif tells the story in his autobiography, Louis one day in 1886 invited Grif over for dinner. The rest, as they say, is history — Grif and Tina’s tragic history. Grif was 36 years old, and Mary Agnes Christina was 23. In his autobiography, Grif briefly describes the courtship during the spring/summer and then the wedding on January 27, 1887.[10]

1887 marked significant changes for Grif. He listed himself solely as “capitalist” in the city address directory, with no reference to ranching. Then, of course, he had married into the Mesmer family and was now truly part of the city’s social fabric. “All that he touches turns to gold,” The Herald gushed in describing the groom the day after the wedding. “Broad acres, and rich mines, flocks, herds, and wealth in Protean forms, and Plutonic magnitudes.” The bride, it went on, “is the daughter of one of Los Angeles’ oldest and most respected citizens” and, to boot, “speaks nearly half a dozen languages.”

The Times headline was admittedly dull but to the point: “Union of Two Very Wealthy Los Angeles Families”. The service was at the Mesmer home, the papers noted, but what was left unsaid was that a Catholic church wedding had proved impractical given that Grif opposed Catholic doctrine. It didn’t seem like much of an issue at the time, after all they agreed on a non-church wedding, but over the coming years religion would drive a wedge between Grif and Tina.

The Times played up a honeymoon/wedding tour that would be “far more extensive than anything of a similar character ever contemplated by any bridal party from this place.” Leaving by train, and in a private Pullman car, the newlyweds were to first visit San Francisco, then Yosemite, the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone before touring East Coast cities and even Europe. But they never did make it to the Old World — by early May, Grif was back in Los Angeles to tend to legal matters tied to Tina’s recent inheritance. He was also anxious to cash in on a land boom going on across Los Angeles.

Tension Over Inheritance

While there’s no reason to think Grif was not fond of Tina, the courtship did develop while Tina was inheriting a 240-acre farm (walnuts, grapes and oranges) from Andre Briswalter — a family friend who, in death, became a central part of this tragedy. Grif certainly knew about the inheritance even before he courted Tina as it was news across the city by early 1886. And it also became clear two decades later during Grif’s trial that he had threatened to break off the engagement unless he obtained control of the land, which was in a prime development area south of downtown.

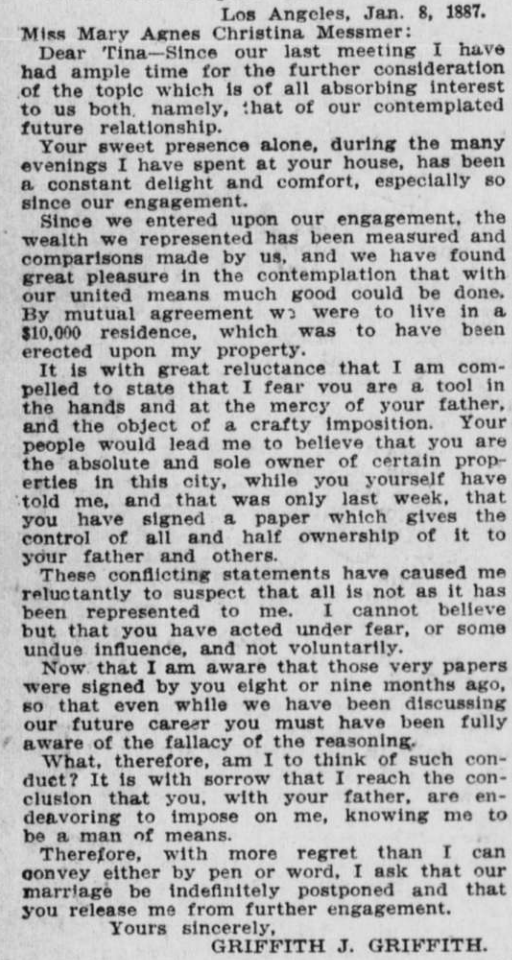

Of course, it was common back then for the husband to manage the family money. But the fact that Grif spelled out his threat in a letter does make one wonder. “I fear you are a tool in the hands and at the mercy of your father,” he wrote Tina on January 8, three weeks before the wedding (see letter below). After describing at length how he felt she might even be part of a scheme to put her fortune in her father’s hands, he concluded: “With more regret than I can convey either by pen or word, I ask that our marriage be indefinitely postponed, and that you release me from further engagement.”

Determined to have her daughter marry, Tina’s mother quickly stepped in and promised Grif he would get title to the land. Tina first transferred the deed to her brother Tony, who then gave it to Grif, all so that Grif could honestly say he didn’t get it from his wife. But the family mistrust only deepened. Tina’s brother Joseph would later write in his unpublished memoir that Grif even interrupted his own wedding reception to sign the deed transfer before leaving for their honeymoon. “Griffith made it his business to make my father’s acquaintance,” Joseph insisted, so that he could then meet Tina, “who had acquired through bequest a very valuable piece of income property… This was the objective that the pretended millionaire was after, who coveted the valuable prize.”[11]

So began a marriage hailed by local papers but which, behind closed doors, was fraught with tension over religion and money. Fortune hunter, or not, Grif would soon use his wife’s inheritance to create a real estate conglomerate. A quick sale of much of the Briswalter tract would net nearly $1 million (about $34 million today) and set up the financial conditions for Grif to seriously consider donating most of his beloved Rancho Los Feliz.[12]

- At trial, the Herald reported on February 25, 1904, Tina testified that her understanding was Grif was awarded the title of colonel by Henry Markham when he was California's governor from 1891-1895. But no state record could be found to confirm that. Markham was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1885 so it is possible he acted then, but even if that happened it would simply haven been an unofficial honorific. It's more plausible that either Grif adopted the title or, if we want to give Grif the benefit of the doubt, reporters mistakenly referred to him as colonel and Grif made no effort to correct it. ↵

- Times, December 4, 1891. ↵

- Horace Bell, On the Old West Coast, p91. ↵

- Eberts in Griffith Park, pp21-23, chronicles the Ostrich Farm era and locates its center near where the Griffith Park Merry-Go-Round sits today. ↵

- Herald, June 1, 1886. ↵

- Ervin King, "Boys' Thrills in Los Angeles of the '70s and '80s" in The Quarterly: Historical Society of Southern California, December 1948, pp302-316. ↵

- Franklyn Hoyt, Railroad Development in Southern California, USC History Dissertation, p123. ↵

- Times, December 5, 1886. ↵

- Nina Fresco, in her upcoming book Along Came Jones, notes the irony that the ostriches were eventually shipped to Santa Monica on the Los Angeles County Railroad, which had earlier absorbed the Ostrich Farm Railway. ↵

- More might be known about Grif's feelings but at that point of his autobiography, two pages have been removed. A penciled note on the autobiography's cover page states that historian Charles Larsen, presumably asked to review the manuscript, advised omitting those pages. The copy resumes with a short paragraph on the wedding, followed by an even shorter paragraph on the birth of Vandell. After that, no further mention of either Tina or Van. ↵

- Joseph Mesmer Papers; Mesmer's draft memoir includes a seven-page chapter titled "Griffith" from which this description is taken. ↵

- The tract also allowed Grif to have the ego boost of seeing a street named after him -- a fact cemented in the local who's who of the day, p231 of the 1901 Historical and Biographical Record of Southern California. Griffith Avenue, at just over a mile, still runs within what used to be the Briswalter tract, from East 14th St. to just south of Jefferson Blvd. ↵