13 The (Soft) Verdict & (Hard) Sentence

MARCH 3 to 10, 1904

“While she was begging for mercy and asking for a little time in which to pray, you discharged the murderous weapon full in her face … I think a more aggravated assault I have never heard of in the experience of fourteen years on this bench.”

—Judge B.N. Smith admonishing Grif at sentencing on March 10, 1904

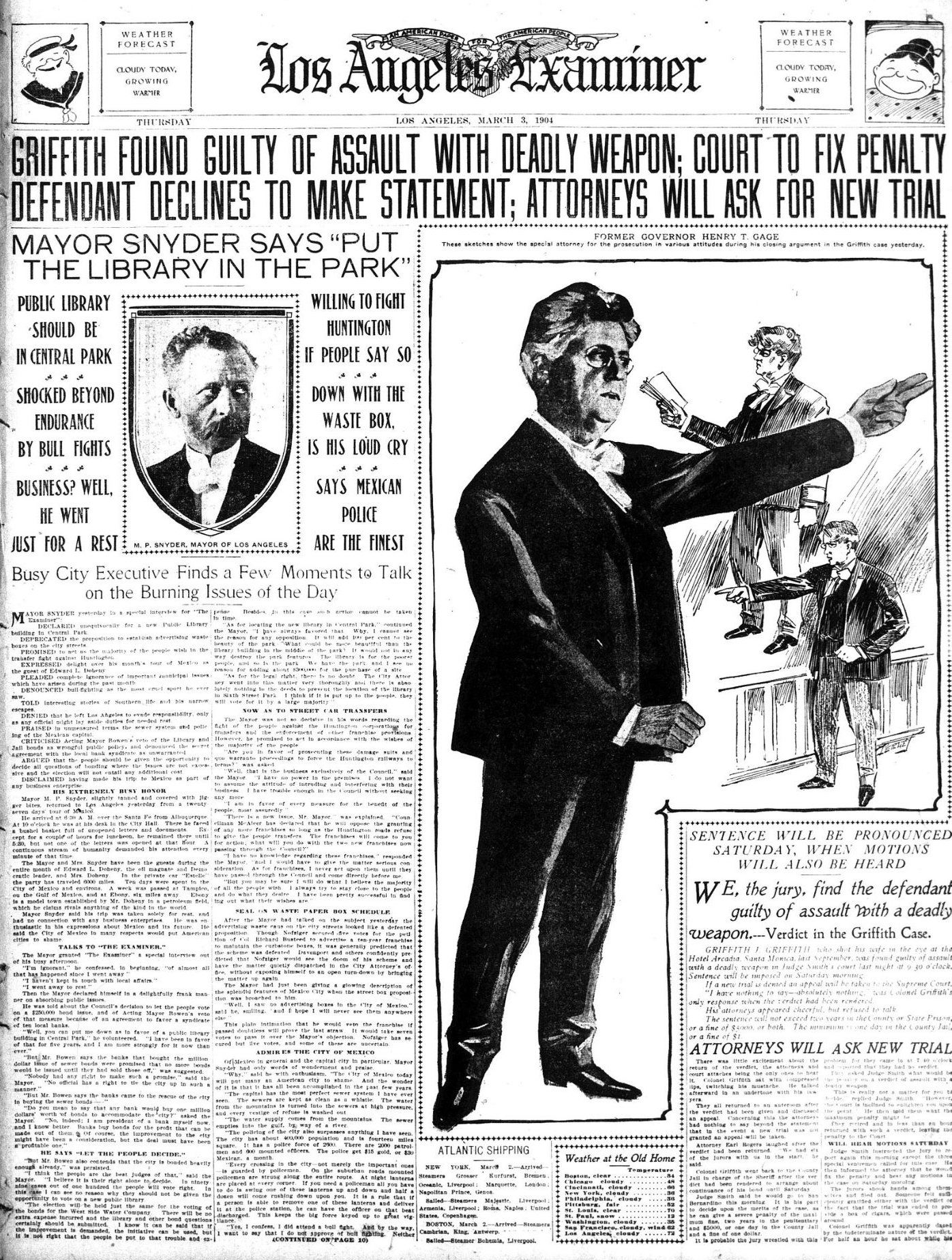

A verdict was handed down, just not the one that either the prosecution, the defense, or the public expected.

Barring a hung jury, i.e. no unanimous verdict, the jurors had four options. In order of severity they were: not guilty; guilty of simple assault; guilty of assault with a deadly weapon; or guilty of assault to commit murder. Any sentencing would be done not by the jurors but by the judge who, while having to follow legal parameters, had latitude in the stiffness of any guilty verdict.

Judge B.N. Smith reviewed those options with the jurors before they withdrew on the afternoon of March 2. He emphasized that if they found Grif to be sane and having pointed the gun at Tina but could not agree on whether his intent was to kill, he would still be guilty of assault with a deadly weapon.

After four hours deliberating, the jury sent Smith a written question. The judge chuckled on reading it, then summoned Grif’s lawyers, who quickly opined Smith should not answer. “Something they (the jury) have nothing to do with,” the judge acknowledged, “but then…,” he murmured as if convincing himself he should reply.

He had no obligation to answer, but clearly Judge Smith felt it would help jurors reach a decision and so he had them brought back into court. It was later revealed that up until Smith’s response, the jury was deadlocked six for acquittal and six guilty of attempted murder — so jurors were looking for a compromise. And their question was this: What were the range of penalties if they ruled guilty of assault with a deadly weapon?

Smith explained that sentence could range widely on his discretion: from as little as a day in jail and a $1 fine (a misdemeanor), to as much as two years in prison and a $5,000 fine (a felony). For context, the other potential guilty verdicts were attempted murder (1-14 years) and simple assault (up to 90 days and/or $300 fine).

Less than two hours later, the jury advised they had reached their verdict. By now it was past 9 p.m. and while Judge Smith called back the teams of lawyers and reporters, the public had been sent home hours earlier and were not allowed back in.

Except for a dinner break, Grif had spent most of those six hours in the courtroom. The Times relished replaying the drama for readers the next day:

“Waiting there hour after hour in the dim half-lit courtroom, almost empty and indescribably desolate, and knowing that behind that fatal door in the corner a dozen men were debating whether to ruin his life or not, was too much for even his iron nerves.

“His drawn face looked like the face of a dead man when the jury entered.

“He had hit about all the human emotions in the course of yesterday, and aching despair was the last.”

As the jury walked in, the Times related, Grif “turned his revolving chair and turned to the court a countenance of awful hopelessness. He looked years older. The stiffness went out of his spine. He was limp and cowering.”

The jury seated, the foreman rose with a unanimous verdict. “We, the jury in the above entitled action, find the defendant guilty of assault with a deadly weapon.”

With no public to raise their voices, the trial had ended in a whimper or, as the Examiner wrote, a “decided anti-climax.” Someone provided a box of cigars for the 12 jurors to share and they shook hands before going their separate ways, satisfied with their compromise. The six who had been set on acquittal could hope that Judge Smith would go easy on Grif, while the six favoring guilty of attempted murder had the hope of some prison time.

How did Grif react? He was spared a long prison sentence, so that was some comfort, but still could be sent away for up to two years — and Judge Smith would decide that at sentencing eight days later. The Herald described Grif as “immovable, displaying neither the gratification at the compromise verdict nor disappointment at not being acquitted.” The Times was not as generous: “As he heard the slow words of the verdict, he seemed to crumple into his chair. His only motion was to constantly pinch his lower lip.”

While the exact sentence was yet to be decided, the jury’s decision made it very clear that Earl Rogers, the city’s pre-eminent criminal lawyer, had utterly failed with his insanity defense — a strategy that had already cost Grif dearly in terms of public image. From benevolent park donor to crazy, drunk capitalist — and for what? A verdict finding him guilty of assaulting his wife with a deadly weapon.

The Times reinforced the image of a thoroughly destroyed Grif with its description of how, now a prisoner, he was remanded to the county jail. Escorted by a sheriff, the city’s newest convict “trooped silently downstairs, and across the street, where the great steel door opened and clanged shut on Griffith.”

“He was wilted – crushed,” the Times continued. “It was hard to realize that the humbled, hunched-up little man with pleading eyes, who crept off to jail last night, was the Griffith who used to go swaggering around town with an eloquent cane and flashing eyes.”

Right, Wrong & Riches

The week-long wait for sentencing gave newspapers plenty of time to get the public worked up again. The Express and Record complained that the jurors were wrongly lenient. The Record’s front-page headline read:

FARCE OF RICH MAN’S TRIAL IS OVER

The Express editorialized the entire trial was “farcical … For an attempted murderer — who is a murderer at heart — the only fit consignment is a six-foot cell for the remainder of his natural life.”

The wait also allowed the press to criticize perceived privileges granted Grif. Two days after the verdict, an Examiner headline read:

Convicted Wife-Shooter Parades on City Streets

Highlighted was the fact that Grif, accompanied by a deputy sheriff, was allowed to leave the county jail so as to deal with business matters and then have breakfast at a diner. “The capitalist walked the streets for a couple of hours yesterday as gaily as if he were not a convicted criminal,” the Examiner reported.

The Herald played up Grif’s “special cell”, describing it as “palatial” compared to the others. “While the law treats most convicts alike, in Grif’s case the clutches of the law are sheathed in a glove of silk and elastic,” the Herald lamented. “He occupied what is known as the ‘emergency cell,’ which is fitted up for just such ‘emergencies’ of a man who has moved in the better classes being obliged to remain in jail for a time.”

At the Times, an editorial on March 5 reflected the complete change of heart at the newspaper that initially had protected Grif from humiliating coverage. Titled “Right, Wrong & Riches”, the editorial focused on a major takeaway from the trial: Prosecutor Gage’s assertion that “out of over 2,000 convicts in the penitentiaries of California there is not one rich man.” Coming from a former governor who would be in the know, the Times wrote, “it is certainly a striking and most unpleasant comment upon the administration of the law in the Golden State.” If Grif escapes jail time, the public will infer that money buys justice and soon America “is standing right at the beginning of the downward path.”

The Express went back to criticizing the jury, reproducing an entire editorial from The San Francisco Examiner decrying the “rascally verdict”. “In a ruder but more gallant community,” Hearst’s other California Examiner wrote, the jury “would be tarred and feathered.”

$1 Fine? Or 2 Years at San Quentin?

Finally, eight days after the verdict, it was time to see what justice Judge Smith would mete out. Just before 10 a.m. on March 10, Grif was escorted in to court and sat down to await his fate before another standing-room only proceeding.

“Stand up, Mr. Griffith,” Judge Smith said as he adjusted his glasses.

That prompted scrambling in the courtroom as people, some rising half way out of their seats, jostled to see Grif. The bailiffs quickly restored order, and Grif stood rigid, arms folded.

“His jet-black hair was carefully oiled and combed,” the Examiner observed. “His small mustache, at which he pulled nervously, was like a charcoal line upon his reddish face.”

Grif and his team still had hope that Judge Smith would go easy given Grif’s contributions to society and lack of any previous criminal record. Earl Rogers had even spoken with Smith right after the verdict and, according to the Times, left Smith’s chambers laughing and boasting, “Well, it is pretty good to get him off on a misdemeanor, isn’t it?”

The Examiner wasn’t happy that it seemed Rogers would be proven right. Many people felt the jury, by virtue of its less harsh verdict, had taken “the first step toward the whitewashing of the capitalist,” it reported before sentencing.

On top of that, the newspaper figured that “much pressure had been brought to bear upon Judge Smith, to the end that he would temper justice with mercy.” One of Grif’s own lawyers ran the local Republican Party and Smith was a Republican beholden to that political boss for renomination as judge, the Examiner noted. “There lurked in the minds of many the thought that Judge Smith, upright as he is, might pattern justly by the action of the jury, and, in giving Griffith an easy sentence, satisfy both his own conscience and the importunities of his powerful acquaintances.”

But Grif and his team were about to be disappointed.

“Mr. Griffith, the circumstances connected with this assault are very aggravated,” Judge Smith began. “The assault was made upon your wife, a woman who for sixteen years had been faithful and true and loving and kind and self-sacrificing. At the time of the assault, Mr. Griffith, you caused this woman to kneel, you subjected her upon a prayer book of her church to the most revolting, gross, unmanly and degrading questions that a man could possibly propound to his wife.”

It was also clear to Smith that the gun did not go off by accident. “And while she was thus kneeling you presented a loaded revolver at her face and, while she was begging for mercy and asking for a little time in which to pray, you discharged the murderous weapon full in her face, the bullet striking her forehead, splitting, one portion deflecting downward and obliterating the light of one of her eyes, putting out her eye. She, in great consternation and frenzy, threw herself out of the window before your face and eyes, falling ten or fifteen feet and breaking her arm.”

“I don’t know, Mr. Griffith, how you can expect but the severest penalty that can be inflicted upon you. Indeed, Mr. Griffith, this court had fully made up its mind when that jury went out, that whatever the verdict, if convicted you would receive the extreme penalty of the law. I think a more aggravated assault I have never heard of in the experience of fourteen years on this bench.

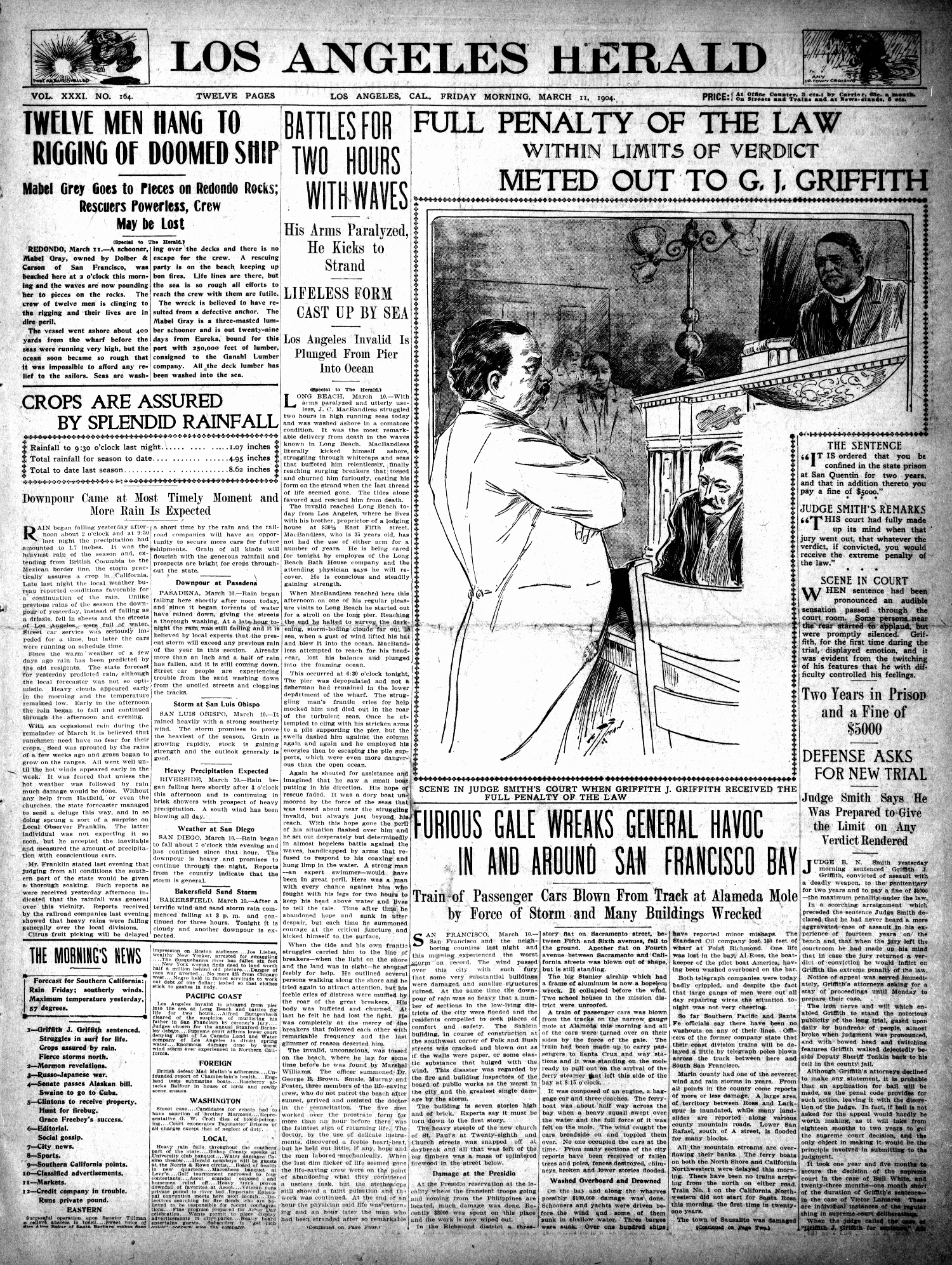

“Therefore, in order to carry out the verdict of the jury, it is ordered, adjudged and decreed by this court that you be confined in the state prison at San Quentin for two years, and that in addition thereto you pay a fine of $5,000.”

Grif had stood stoic to start, the Examiner noted, but “gradually the full impact of the judge’s words grew upon Griffith” and with the judge’s last words Grif “stiffened up as if an electric battery had been jammed against him.

“There was silence.

“Every eye in the courtroom was on Griffith, and he threw back his shoulders and tightened his arms more tightly.

“Even in that hour of his humiliation he was still the poseur. Even the clapping of hands did not disturb him.”

Final Feather Plucked

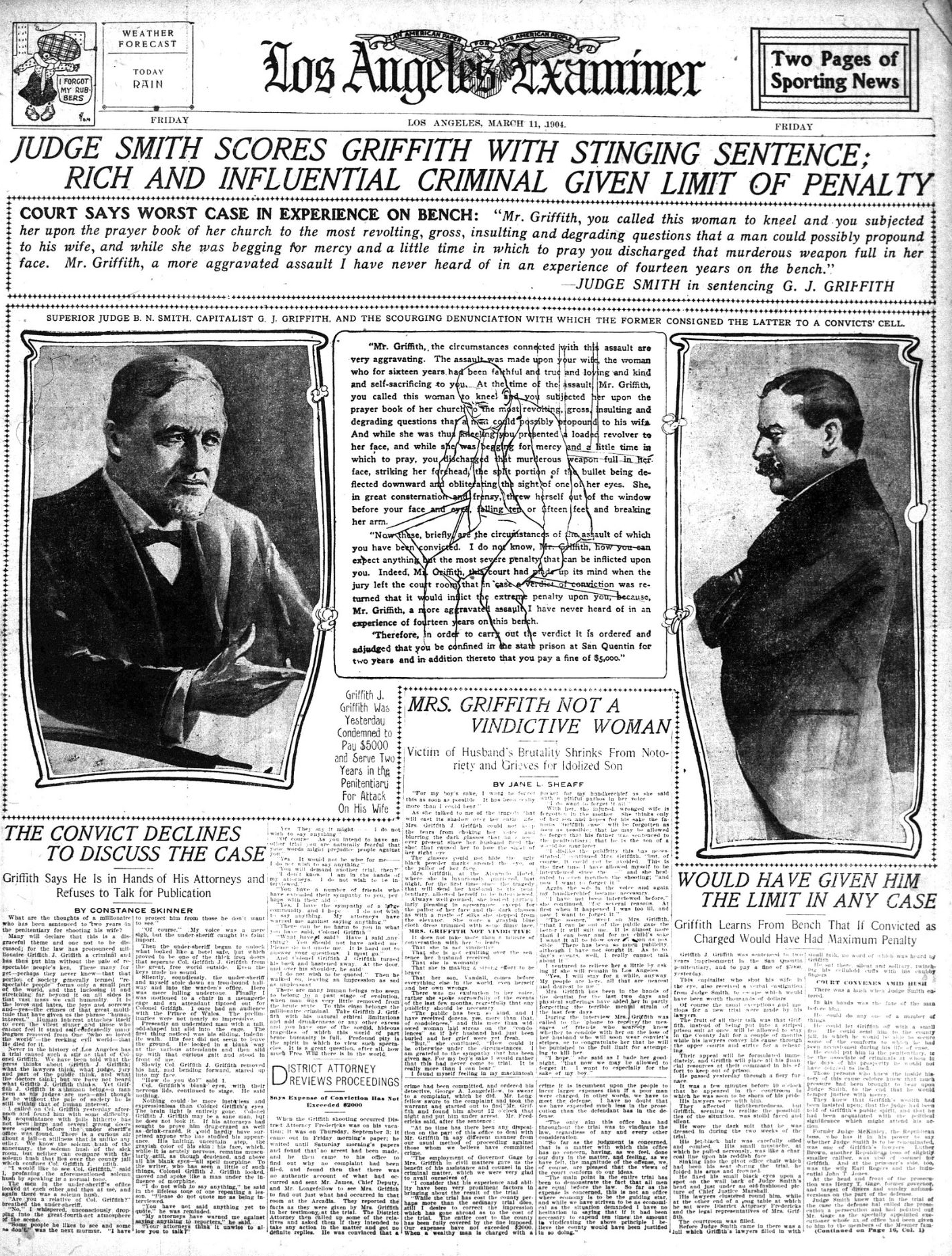

The Examiner wasn’t done with just that description. Hearst’s newspaper let Grif have it with the typeset, lead letters in its print shop. The entire front page of March 11 was dedicated to the sentencing, starting with a two-deck headline across all seven columns. (See image above.)

In a box below were choice words from Judge Smith, followed by another box with his entire recrimination, and then images of Smith and Grif facing one another. The main report focused on the sentencing and what Grif must have been going through.

“If he saw himself as others see him,” the Examiner noted, “he must have known that yesterday he drank the bitterest cup that ever came to him… For yesterday the last one of his gaily colored feathers was plucked.

“He was Griffith, the peacock, no longer.”

Two other front-page stories were unique — they were the only ones, by any newspaper, that during the entire trial were given a reporter’s byline, and both were written by women, a rarity at a time when most reporters were men. The contrast could not have been starker. One report was an attempt to interview Grif that turned into a pathetic profile of the millionaire behind bars. The other was a brief interview with Tina, her only words to a newspaper this entire time.

An unannounced visit to the county jail led to the brief encounter with Grif, who declined any conversation. But that didn’t stop the Examiner reporter from mockingly referring to him as the “Prince of Wales” and “an undersized man with an odd-shaped hat… The first thing noticed was his sliding, indefinite walk. His feet did not seem to leave the ground.”

“There are many human beings who seem to belong to a past stage of evolution, when man was very little removed from the brute state,” reporter Constance Skinner concluded. “To this class belongs the millionaire criminal. Take Griffith J. Griffith with his natural ethical limitations and add drunkenness or any other excess and you have one of the sordid, hideous tragedies of which this world of part brute humanity is full. Profound pity is the spirit in which to view such spectacles.”

The pity shown Tina, on the other hand, was one of deference to an anguished mother. The headline said plenty:

MRS. GRIFFITH NOT A VINDICTIVE WOMAN

And the secondary headline said more:

Victim of Husband’s Brutality Shrinks From Notoriety and Grieves for Idolized Son

“For my boy’s sake I want to forget this as soon as possible. It has been really more than I could bear.” With those words from Tina, reporter Jane L. Sheaff began her interview. She then described Tina as unable to “keep the tears from choking her voice and blurring the dark glasses that have been ever present since her husband fired the shot that caused her to lose the sight of her right eye.

“The glasses could not hide the ugly black powder mark around her eye, or the pallor of her face.”

Tina was grateful for the countless condolences, the Examiner stated, “and this more than widowed woman laid stress on the ‘condolences’ as if her husband had just been buried”.

“For my boy’s sake,” Tina said, “I would rather that this had never come to trial.”

The brief interview was paused by phone calls from friends “who scarcely know whether to condole with her on the loss of her husband who will soon wear convict’s stripes, or to congratulate her that he will be punished to the full limit for attempting to kill her.”

The chat ended with goodbyes and Tina’s parting words: “I hope that now we may be allowed to forget it. I want to especially for the sake of my boy.”

The Times and Herald had their own takes on Grif’s day of judgment? The Times seemed ready to forget Grif, after all dwelling on a fallen millionaire doesn’t help the image of the local elite or, for that matter, “the land of sunshine”. And so Grif’s sentencing was relegated to Page 2 of Part II, and had none of the Examiner’s drama, flair, illustrations, photos or headlines.

The Times did take a few pot shots at Grif, first gossiping a day after sentencing that locals were wagering on whether the Supreme Court would back Grif’s pending appeal. A few days later, it reported on a way to rename Griffith Park even though the city, in accepting the donation, stated it could never be renamed. The idea was to challenge Grif’s deed to the Rancho Los Feliz since land transfers were murky back in the 1800s. If successful, then the city could annul the donation of Griffith Park, seize the land and name it something else. Nothing ever came of the idea, but it does show how the Times was ready to erase Grif from Los Angeles history.

The Herald, for its part, landed somewhere between its two main rivals. The sentencing took up a third of its cover page. and its editorial page lamented the jury’s “miscarriage of justice” while praising Judge Smith who “demonstrated that it is possible in California to mete out equal justice to the rich man and the poor … The more wealthy the man … the greater should be his disgrace and punishment when he violates the laws”.

“Griffith Jenkins Griffith, ‘prominent citizen,’ who had almost induced the community to accept his own valuation of himself as a philanthropist,” the Herald added, “will no longer conduct tallyho parties to the canyons of Griffith Park, but … will wear the convict’s garb.”

Grif wasn’t sent immediately to San Quentin, however. An appeal to California’s Supreme Court meant continued jail time in Los Angeles — a yearlong wait during which more Griffith drama played out. It started with Grif being sued by some of his earlier lawyers over their fees, and ended with Tina being granted a divorce. In between that drama Griffith Peak, the tallest point in the park, was renamed, and Van, just 15 years old, ran away to San Francisco in hopes of starting a new life away from the scandal.