18 Wife, Son, Husband & Father

“As one who signed the original deed giving Griffith Park to the city of Los Angeles over fifty years ago I sincerely hope the present City Council will protect and preserve Griffith Park for the generations of the future”.

— Tina in a 1948 telegram opposing plans for a cemetery next to the park

Who better to help understand Grif than the two people closest to him: Tina and Van. Yet neither left a diary nor any detailed reflection to go by, even though they lived decades longer than Grif and, one would suspect, might have wanted to have a say. What we do have are some of their actions and, while mother and son would both recognize Grif as a philanthropist, Van always looked up to his father — perhaps he did not see the enlightened egomaniac described here.

Very little is known about Tina, part of that was her private personality and part due to the time they lived in — it was still a male-centric society. The record shows that she went to Catholic grade schools, played the piano and learned several languages. Between marriage and the shooting, Tina appeared occasionally in newspaper social columns as Mrs. Griffith and usually in conjunction with Grif at some event such as a fundraiser or Jonathan Club dance.

The only times Tina was ever quoted in the press were during trial proceedings. Even there she was very restrained, never mentioning Grif, only her desire to protect Van. “I hope that now we may be able to forget it,” she told the Examiner after the trial. “I want to especially for the sake of my boy.”

There is no evidence that she and Grif ever spoke to each other after the shooting and, judging by the periodic newspaper citations, her post-shooting life centered on helping Catholic charities, playing the card game whist and attending social events. She never remarried and, even with a divorce in hand, was almost always referred to as Mrs. Griffith, not Christina Mesmer, in press coverage.

Tina lived with her sister Lucile and outlived Grif by nearly 30 years, passing away on August 11, 1948. Only once during that time did she speak out publicly and that was to protest plans to allow a cemetery next to the park. She was secure in her conviction that she, too, helped deliver the park that millions of Angelenos enjoy. It was March 5, 1948, and Tina sent the City Council this telegram:

As one who signed the original deed giving Griffith Park to the city of Los Angeles over fifty years ago I sincerely hope the present City Council will protect and preserve Griffith Park for the generations of the future and avoid any development adjoining the Park which might depreciate its value as a great public recreation ground.

She signed it Mrs. M. A. C. Griffith.

When she died five months later she left an estate worth $100,000 (nearly $1.3 million today). Her will stated that since Van had been a beneficiary of Grif’s estate he would receive nothing, though Van’s two children did get $10,000 each.

Several newspapers and even the Associated Press, which provides copy for newspapers around the world, wrote short obituaries of Mrs. Mary A.C. Griffith but not a single one mentioned the shooting and trial. Some noted that she was divorced and the Times was one of the few that acknowledged that Tina was also a donor of the park.

If there was to be a time for Tina, or at least the Mesmer family, to reclaim her name, one would think it would be in death. But, even there, Tina’s connection to Grif is etched in stone. She is buried in a mausoleum crypt at Los Angeles’ Catholic Calvary Cemetery, and the impersonal inscription carries her married, not maiden, name:

Mary A. C. Griffith

Born Los Angeles, California

February 29, 1864

Died August 11, 1948

It was in death, as in divorce earlier, a strange loyalty to the Griffith name.

Life Father, Like Son – Sort of

As for Van, only two written accounts exist of any interaction with his father — Grif’s 1905 letter from San Quentin, and a 1916 letter from Van to his father.

From San Quentin, Grif started with his recollection of Christmases past and how Van would wake up anxious to see the presents left by Santa. Grif’s tender and even nostalgic reflection ended with “Oh! how the givers would enjoy the pleasure of making you so happy! Those days have passed and gone, never to return.” Grif then turned to his own experiences in prison before asking Van how he was doing. That allowed an understanding father to bring up an issue Van was certainly nervous about: the son had rejected the father’s wish that he attend Stanford University. Instead of reproaching Van, Grif wrote “don’t you feel discouraged” since many great men did not need university to succeed.

Van, for his part, had many chances to talk about his father but never did. He did start recording an oral history at UCLA but instead of an honest reflection he read pages from Grif’s autobiography. The only known written account is a 1916 letter Grif asked Van to draft so as to renounce any claim to challenge Grif’s will once he died. It starts with “My dear father,” and ends with “As ever, I beg to remain, Your son”. But the copy in between is just standard legal jargon, no further characterization of their relationship.

Grif himself, in his autobiography, had just one sentence about Van and that was recalling his birth as “the only child of our marriage.”

But looking at Van’s actions as he grew from boy to man, it would be hard to imagine any son more like and loyal to his father — more loyal than to his mother, even after seeing her shot in the face.

That loyalty, perhaps even devotion, was shaped at a very young age. Van was eight years old when his parents donated Griffith Park. But it was Grif, not Tina, who became the toast of the town. Remember it was Grif who was made a lifetime member of the Chamber of Commerce. Grif who was “knighted” at the 1897 Fiesta. Grif whose name constantly appeared in newspapers. Grif as a celebrity must have left an impression on Van that his dad was something special. Someone he could look up to, whereas mother was relegated to taking care of the family.

That closer connection to dad became clear during the divorce and after Grif’s sentencing. Van, 15 at the time, did not want to live with Tina’s stepmother while Tina was in hospital and divorce proceedings were underway — no, he wanted to stay with his father. And after the sentencing, when it became clear that his father would spend time in prison, Van ran away from his mother and tried to start a new life in San Francisco.

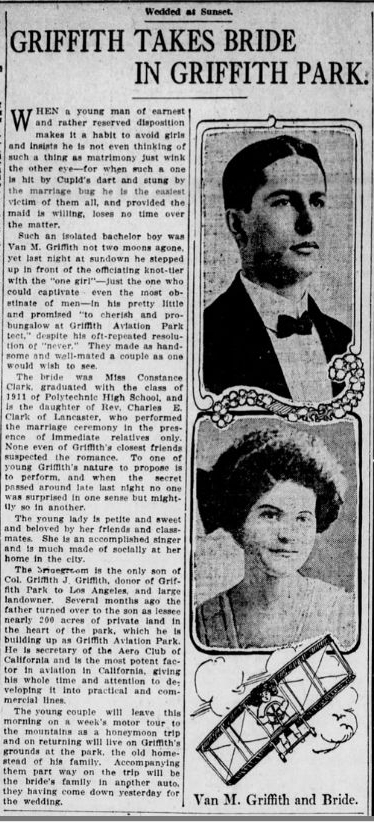

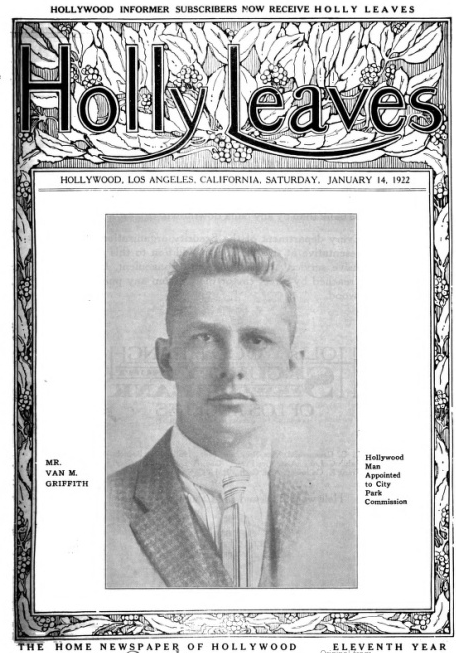

When Van was found, he had no choice but to return to his mother. He finished high school and, instead of going to college, developed a passion for flying machines. Then in 1910, at age 22, he landed an internship at the Los Angeles Times — starting out in newspapers just as Grif had done. He would later become a police reporter for the liberal Los Angeles Record, and then worked in the district attorney’s office as an investigator.

Besides aviation and paid work, Van also started taking on the role of Griffith Park steward. As a child, Van not only saw the platitudes bestowed on his dad but he personally had visited many parks across the United States in Grif’s company. Those visits planted seeds that would later blossom into Van’s own stewardship.[1]

Van’s first park-related action, in 1914, was to become superintendent of a private bus service into the park. Grif, tired after 18 years of trying and failing to get rail service there, decided to help fund the service himself. Van even drove one of the buses and in May 1919 the city absorbed the service and appointed Van its Commissioner of Motor Bus Transportation for Griffith Park.[2]

Grif passed away just two months later, but he had lived long enough to see his son begin his stewardship role. And three years earlier, in 1916, he had drafted a will leaving most of his fortune to a trust that would pay for the observatory, theater and future park amenities. Grif named Van one of three trustees and asked his son to honor his will by writing the letter vowing to never contest it — which Van dutifully agreed to.

The bus service was only the beginning of Van’s public service. In November 1920, he began a new city position of Griffith Park developer. It was unpaid but gave Van a prominent voice within the Parks Commission to oversee not only the observatory and theater but also future improvements like playgrounds, the zoo and sports fields.

Van was now learning how to move within the city’s political system and in 1925 proved instrumental in drafting a city charter, later approved by voters, that set a fixed annual levy for parks and recreation. In the 1930s, much like his father had in the 1890s, Van pushed for political reform and in 1938 helped unseat a mayor whose administration was seen as corrupt. The new mayor, Fletcher Bowron, first appointed Van to the Police Commission and within a year Van had moved to what seemed like destiny: park commissioner.

Van passed away in 1974, having lived a crime-free and honorable life — he had even refused lifetime passes to the Griffith Observatory, stating it violated democratic principles.[3]

To sum up his life, he was the best of his father without his father’s ego and other faults. Especially in marriage, Van was far different from Grif, having been married to the same woman for 62 years until his death. Moreover, Constance Griffith, while no fortune in hand, always had Van’s support to pursue her own interests of protecting voting rights and civil liberties.

Still, Van’s last act was a definitive statement. Along with his beloved wife and two children, Van now lies not next to his mother at Calvary Cemetery, but with his father at the plot that Grif had been so focused on leaving as the Griffith family resting place.