Introduction

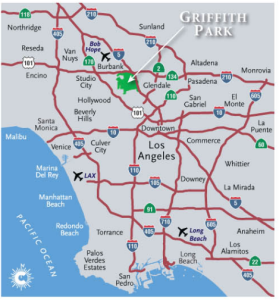

Why should you care about this story? A wealthy husband tries to kill his wife — that might get your attention at a dinner party, but to read an entire book about it? This story does have a “trial of the century” feel to it, but it seems every generation, in every city, has one of those. No, the reasons to stick with it are actually deeper. As the title suggests, it explores how a do-gooder, Griffith Jenkins Griffith, turned into a would-be wife killer. But it also shines a light on Christina Griffith, who besides being the victim here has never been fully recognized by the city of Los Angeles for helping her husband establish Griffith Park, the world’s largest park in the heart of a major city.[1] Finally, their history together happens at a unique time and place — when a nation’s expansion west turned a forsaken town, Los Angeles, into a mecca-city and then the mega-city it is today.

Griffith J. Griffith, the Welsh immigrant at the center of this story, was living the American Dream — from poverty to fortune, family, fame and philanthropy. The creation of Griffith Park in 1896 should have been plenty for a long legacy. But then he jeopardized it all seven years later, shooting his wife in the face after accusing her of infidelity and of trying to poison him on behalf of the Catholic Church.

Today, Griffith Park is familiar to most residents of Los Angeles and many a visitor. But few know of the crime that turned that legacy from one of philanthropic visionary to ego-driven drunk and now forgotten benefactor.

Grif, as his friends and family called him, came to the United States from Wales as a teen in 1866 and within a decade had made a fortune in mining — well, actually in the art of mine speculation and possibly manipulation. More on that later. In any case, that fortune allowed him to buy the 4,071-acre Rancho Los Feliz in Los Angeles. He married a wealthy local, Mary Agnes Christina Mesmer, and soon a son was born to carry on his family name. In 1896, he made that enormous gift to his adopted city: 3,015 acres from his rancho.[2]

That, along with other actions and smaller donations, made him not only Los Angeles’ first major philanthropist, it also created the sense that Grif’s life experiences had made him something of a visionary. Parks are needed not as a retreat for the wealthy, he argued, but as safety valves for the working class stuck in cramped, unhealthy quarters. He later funded the Griffith Observatory and Greek Theater[3] to bring science and art to a greater public. In other ways, too, he was ahead of his time — or at least ahead of how his wealthy peers acted. A city needs industry, not just orange groves, he postured, and he put his money where his mouth was by starting a tile factory that for a short time became one of the region’s largest employers. He also waged a very public campaign to turn prisons into reformatories providing a second chance — a view he came to embrace after his own time at San Quentin.

But that vision came with an ego and heavy drinking. His tragedy played out just as Los Angeles was evolving from a backwater town into the envy of a mighty United States of America and its new president, Theodore Roosevelt. Los Angeles, too, had it all — sunshine, beaches, plenty of farmland for those iconic orange groves, and even an ocean gateway to the Pacific and the Orient beyond. Grif’s story illustrates not just an American Dream come and gone, it also shows how California, particularly Southern California, became a mecca for dreamers at the turn of the 20th Century. People like Grif anxious to make their mark in a promised land.

Northern California boomed first thanks to its gold rush. The few who made fortunes there included Grif, though his was relatively small compared to most “fortunes”. Many of those few then parlayed their wealth into real estate, railroads and/or trade. America had just connected the coasts by rail, and soon new shipping ports would expand opportunities across oceans.

Grif had a flair for flaunting his position and wealth — both of which were enhanced by Mrs. Griffith J. Griffith, formerly Mary Agnes Christina Mesmer. The Mesmer family had status in Los Angeles, where Christina’s father was one of the first to make a fortune. And, shortly before marrying, she inherited farmland near downtown that was ripe for development.

Given that the victim here was Christina, known as Tina by family and friends, one might ask: “Why not tell her story? She’s the one who suffered.” True enough, but remember this happened at the turn of the 20th Century. Women generally were forced to keep low profiles, and in California they couldn’t even vote until 1911, so little was documented about Tina’s life. She left no diary or autobiography, while her social and charitable activities were rarely noted in newspapers.

It was still a man’s world to conquer or drown in — and Grif did both in just 20 years. He had the potential to be remembered as a respected philanthropist and yet he died ostracized. Grif’s burial was a sad affair with just a few people paying respects. Local newspapers hardly mentioned it. The only saving grace for Grif’s legacy was that no newspaper reminded readers that he had been convicted of shooting his wife. It’s hard to fathom how this could befall the man who donated what was, and still is, the largest park in the middle of a major city anywhere on the planet, but then you haven’t heard his story yet, have you?

Let’s start at the bottom.

- A qualifier to "world's largest (urban) park" is required here: Julia Czerniak and George Hargreaves in Large Parks list Fairmount Park in Philadelphia and Casa de Campo in Madrid as slightly larger urban parks than Griffith, but the former was cobbled together from several parks and the latter is outside Madrid's center. Also, several other urban parks are larger but none are as centrally located within a major city. For a list, see tpl.org/resource/150-largest-parks-2010. ↵

- Mike Eberts in Griffith Park: A Centennial History provides the most in-depth account of the park's creation and first 100 years, as well as significant biographical details about Griffith. ↵

- Today, the spelling of Greek Theatre ends in "re" but originally, as per its dedicatory pamphlet in 1930, it was the Greek Theater. The "er" spelling is maintained throughout the book for consistency. ↵