Solving Problems through Careful Consideration of Philosophical Dialogue

Understanding the Terminology

This chapter will cover terminology and the two approaches related to moral problem-solving:

- objectivism, and

- subjectivism.

There are two different approaches to moral problem-solving. The first one is the perspective of objectivism. Objectivism is the belief that there is knowledge, Truth, or concepts that are distinct from individual perception that we strive to make sense of and guide us in our attainment of knowledge. In ethical terminology, objectivism is best equated with the term absolutism. Absolutism refers to the belief that there is universal Truth or universal concepts of “right” and “wrong” that exist regardless of individual perception representing reality and knowledge. Apart from this stance exemplified in objectivism and absolutism, there is the philosophical realm of subjectivism. This terminology refers to the belief that truth, reality, and morality are understood through individual experiences or perceptions. Thus, subjectivism argues that our knowledge of anything is contingent on our own individual understanding or interpretation. The moral terminology best associated with this belief is the concept of relativism. Relativism is the belief that morality is only an expression of personal preference or individual interpretation. Thus, rules of conduct or moral expectations are only a product of personal expression or perhaps even just opinion. This argument is perhaps the most complicated and important dilemma found in thinking and problem-solving and has been analyzed for centuries in all cultures. How one interprets the world, their individual place in that world, and their conceptions of “good” and “bad”, will heavily impact how they interpret problems and how they solve dilemmas on a daily basis.

Other classifications one might encounter

The objective and subjective stances that people may take on any issue relating to problem-solving can be divided into these seven categories according to thinking experts.

The first one on the slide is the definist religious authoritarianist thinker. This thinker approaches decision-making from the standpoint of arguing that objective moral assessment comes from some supernatural power or authority that has created the conceptions of preferred human behavior. Thus, moral decisions are equivalent with the supernatural power’s commands or expectations. The second thinker is the nondefinist religious authoritarianist who argue that moral decision-making is rooted in a supernatural power’s commands of what can best be assumed to be “right” and “wrong”. But, unlike the definist religious authoritarianist, the nondefinist religious authoritarianist denies that the meaning of moral judgments can be defined strictly in terms of supernatural command. Though both thinking processes appeal to objectivism, they differ in the extent of that objectivism’s direct connection to such a supernatural power through moral reasoning.

The nonnaturalist thinker believes that morality or decision making is contingent on truth that is not found in the natural realm. Thus, values or virtues do not exist in our natural world but instead in reference to the non-physical or supernatural realm. The naturalistic objectivist maintains that truth is objective and found in our natural realm. This belief might appeal to natural order or natural law. While the naturalist objectivist argues natural process or natural law dictate what is “right” or “wrong”, the nondefinist naturalist objectivist believes that there is no correlation between natural processes and moral thinking in spite of possible connections. The last two categories focus on the role of the individual or subjectivism in determining morality or “good” decision-making. Personal subjectivism argues that whatever one’s conscience decides is the right decision; while, egoism argues that moral thought is wholly based on individual preferences and that there is no obligation for individuals to consider the “good” or “betterment” of others.

A Profile of Subjectivism

Thinking and decision-making factors inherent in our world are not that far removed from those of the Ancient Greeks. They recorded their problems and discussions and those writings were passed down. Today, we are able to read and learn from them. The two best examples of this subjectivism and objectivism interacting can be found in the arguments of the Sophists and Socrates.

The subjectivist thinkers who were known during their time as the “wise ones” when many philosophers, were involved in both academic and observational study of the world. They studied everything from cosmology, to language, and the conceptualization of human thought. A literal academy emerged in the city of Abdera in modern day Greece where wealthy sons were educated in, what this group believed, as the truth or the concept of true wisdom. Wisdom was found in the belief in individualistic thinking or “extreme skepticism.”

Extreme skepticism focused on the following questions:

- Are there real ethical principles or is morality merely a set of arbitrary conventions?

- Are the laws of the state comparable to the laws of nature or mere arbitrary rules?

- Are the genuine moral laws, norms for evaluating human behavior, comparable to the laws which govern physical nature?

To answer these questions, they formulated a philosophical, moral, and decision-making system based on the concept of relativism and subjectivism. They argued that moral principles or concepts of “right” and “wrong” were relative since knowledge is relative. The only thing worth studying in terms of leadership, was the art of debate or argument so when one’s relative opinion met one’s other relative opinion, the winner would be determined by the individual most talented in debating their viewpoint.

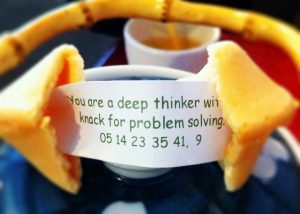

Protagoras c490-420 BC

This perspective is summarized by Protagoras of Abdera, a teacher in the academy from 481-411 BC. He said “man is the measure of all things, of things that are, that they are, and of things that are not, that they are not”, or decision-making should be determined by the relativity of truth, the relativity of morals, and the concept of equality for all, as no opinions were better than others in quality or content. The equality feature led the early Greeks to argue that the best form of government was a pure democracy where decisions could be best determined in a context of voting and majority rule. Therefore, the Sophist viewpoint of Ancient Greece, argued that one’s perception was truth and that morality or decisions of “good” or “bad” and/or “right’ or “wrong”, were not useful unless understood in the context of the determination of social norms or codes. This presents an interesting propensity that we all have to believe that our reality is the preferred perspective to accept. Listen to Julia Galef’s discussion on why we think we are right even when we are clearly wrong.

A Profile of Objectivism

The contrary argument to Sophist approach was espoused by the Greek philosopher Socrates. Plato argued that objective Truth could be found through the pursuit of greater knowledge and education. Plato wrote during an age in Mediterranean history, where the ideas of Sophism had significantly impacted the societal norms and morals of many Greek city-states at the time.

Socrates argued that decisions in life must be directly tied to the pursuit of what can best be termed “Goodness” or the concept of the “Good”. This could be pursued through the constant process of questioning; questioning that led us to seek out Truth and gather evidence, not to give up because of our subjective processing. He asserted that there was an universal or objective Truth apart from human perception or perspectives that helped guide us in our decisions. The more we reasoned and grew in our self-knowledge knowledge and the world around us, the more this reality was revealed to us. Patterns of life are predictable and reflect a system in which our thinking and reality could best be understood in terms of forms of hierarchy that coincides with betterment or progress.

Though there are elements of relativity in how we gain knowledge of what is “Good” and in the deviation in how humans reach “Good”, Socrates philosophy is clear in that decisions of all kinds should be understood in the context of a universal conception of “Goodness”–not merely individual desires or individual perceptions. In short, we must take into consideration the greater “Good” because there is more to this life than our existence or reality.

At the root of these arguments is Plato’s belief that there all “Ideals” that we inherently have knowledge of and help to guide humans to assess making value judgments. These ideals are represented by characteristics of preferred human behavior that are not subjective but objective. In this thinking, we find strong evidence for the concept of comparison in a monistic framework, where knowledge of “good” and “bad” are found in the comparison of imperfection with perfection.

Platonic thought asserts that we have concepts of “Goodness” implanted in us in the realm of ideas, but we must find those conceptions through our diligence in pursuing them through a life of moderation, awareness of the ways of the world and reason. The world provides clues to find that knowledge but we must also acknowledge that the world is imperfect.

Goodness is found in harmony, virtue, and rationality but not always in the easiest and most convenient manner. From our knowledge, we discover values and virtues that are passed down from generation. These values and virtues are not relative or merely based on individual assessment, but are part of hierarchy of “Good” that is part of our humanity.

What about happiness?

When contemplating the objective and subjective nature of the world and moral determination, inevitably the question whether there is a correlation between living morally and happiness emerge.

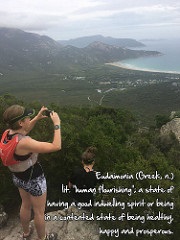

Contrary to Plato and the Sophists, Aristotle believed that true morality and/or ethical living was not found in intellectual contemplation/pursuance of the right pleasures or in the one virtue of appropriate care of others; instead, Aristotle was convinced that true ethical behavior was to be found in the true knowledge of individual happiness found in “living well”. This conception, though universal in the sense that there are factors that are the same in how all of us pursue them, is highly personalized and based upon one’s willingness to search in great depth through practical knowledge and understanding on a daily basis of what true happiness or “eudaimonia” looks like. In his analysis, we should pursue virtuous behavior or characteristics such as honesty and trustworthiness, because such values come from our rational soul, an instrument that promotes constructive reason and promotes goodness for ourselves and others. In observing the world around him in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was convinced that people were misled, believing that true happiness was based on one’s conception of material goods or power. Though these concepts are not inherently problematic, the obsession that humans often display towards these items, leads the world and themselves to be unbalanced, as best understood in his description of the “doctrine of the mean”. In this concept, Aristotle clearly writes that true ethical leadership and moral decision-making is based on the understanding of true balance of extremes, where the negative effects or destructive nature of one extreme or another, is minimized. How do we do that effectively in a world that pushes us to focus on the end result of profit and physical rewards?

Aristotle’s solution, the concept of living a virtuous life, can be found in a couple of practical suggestions. One, individuals must set reasonable goals that are individualized and focus on the belief that a balanced, healthy life emphasizes living well, a concept found in reason and its practical application. Second, one will make better ethical decisions when one understands that living well is not based on the accumulation of wealth, material goods, or power; instead, it is based on the habitual practice of virtuous or reasonable conduct where the individual is validated and others because of these practices, reciprocate. And last, this concept of balance or “mean” emphasizes the idea that though the end result of ethical behavior is true happiness, that true happiness can only be found in the true exploration of one’s very being, so that one can truly know what one was put on this earth to accomplish; namely, one’s true mission or the fulfillment of what one’s purpose is.

Dan Gilbert discusses why we make bad decisions (33 minutes) in our lives. Pay attention to where Gilbert agrees with Aristotle’s assessment.

When one finds true meaning through adherence to reason, proper virtue, pursuit of goodness, and balance, individuals, groups, and society will benefit and honesty and trustworthiness will return. Aristotle’s conception of moral excellence argues that true leadership comes from allowing individuals to pursue their passions in a truly virtuous manner where material goods are secondary to lives devoted to characteristics of human behavior that bring true happiness and goodness. Those factors can only be found in working through constant and habitual practices that emphasize moral living. If we want true, long-term happiness, we must be willing to focus on changing these habits by pushing ourselves and others to “live well” in a long term framework, rather than in an artificial short-term framework that often ends in unhappiness and unethical behaviors and stances.

Listen to Chris Gardner,’s speech in 2009. Chris inspired the famous movie The Pursuit of Happyness, 2006. In the speech, look for the correlation between Aristotle’s conception of happiness as it relates to morality and Gardner’s view.

What about Pleasure and Pain?

Beyond the evaluation of happiness and morality, we must also consider the role that the influences of pain and pleasure play in determining our moral evaluation within the context of objective and subjective thought. One important theory to study is Epicurean thought.

Epicurean thought is often known for its close connection to hedonism. Hedonism is the philosophical perspective that life should be centered around creating the most happiness for one’s self. Usually, this is interpreted as happiness grounded in physical pleasures. The perspective of hedonism emphasizes the fact that one should make decisions for the short term and look for immediate gratification because our time in this world is, at best, fleeting. This “supposed” connection between hedonism and Epicurean thought has been grossly overextended.

Contrary to English definitions and the assumed meaning of the term Epicurean over time, the philosophical position of Epicurus is not based in hedonism. The belief, at its core, runs counter to this. Epicurus lived in the 4th century BC, when many wealth Greeks believed that their culture and social morals were in decline. Epicurus traveled the known Mediterranean Greek world at the time, and after years of observing this decline, came to the conclusion that many Greeks did not have their priorities in the correct order. He returned to Athens in 306 BC and began to encourage those around him to withdraw from public service, looking to themselves or their inner being to find contentment and happiness, not through others around them or through society’s expectations.

Where Epicurus is most misunderstood is in his explanation of pain and pleasure. He believed that life’s decisions were determined by the interaction of these two powerful forces in our lives. What we choose, in terms of an outcome, directly connects to our understanding of the potential “fall out” of our decisions determined by the pain and pleasure equation. Epicurus argued that we should seek out what he termed the “peace of mind” principle. This “peace of mind” principle stressed that we should evaluate whether our decision or decisions would create more pain or pleasure for ourselves and those involved. In addition, those decisions must be contingent on long-term intellectual investments which he considered the most beneficial. Thus, contrary to popular thought today, Epicurus did not simply advocate a hedonistic perspective of living.

At the core of good decision-making according to this theory, is the dilemma of whether to live a life avoiding pain or seeking pleasure. He delineated the difference by explaining that a life lived simply “avoiding pain” was a de-active form of life with little return on one’s “pleasure investment”. One ended up living a life not maximizing their potential for pleasure. The alternative approach he defined as a life spent actively seeking pleasure or the “right” pleasures. This life, he argued, was the most satisfying and moral, as decisions made based upon that perspective, would offer everyone involved, a greater happiness factor or level of contentment.

This idea of contentment was based on long-term investment in the arena of the mind. Rather than focusing on the end results of a life lived that pursued trivial and materialistic pleasures, Epicurus strongly believed in the morality of decisions made in reference to intellectual pursuits that, he was convinced, transcended the limitations of the short term. Epicurus relies upon the strong belief that happiness is not directly tied to ecstatic or high forms of pleasure or the concept of pleasure found in the attainment of all desires. Both factors discussed are impossibilities and therefore the pursuit of them foolhardy. Instead, many of these thinkers like Epicurus, come to the determination in their own life and through the lives of others, that true happiness is found in the balance and contentment that one seeks, finds and then carries out on a daily basis.

As a result, Epicurus’ argument, ironically, emphasizes that one gain control of one’s decisions by keeping in check one’s thoughts and emotions. He believed that individuals who were well-schooled in thinking strategies and good decision-making, clearly understood the end result of their thinking processes and could see the truth—that namely true happiness was found in careful and deliberative good moral evaluation; essential for those who were mindful. In following this “self-control” aspect of his theory, Epicurus was convinced that one gained “true freedom” or the ability to escape from the troubles of mind and body. It was through intellectual pleasure, in particular, that one could find the greatest reward through learning to practice self-control and adequately weighing one’s own interests with those around them. Thus, morality is not found in mere societal dictums or norms; instead, each individual must shoulder the responsibility of seeking out “true” pleasure, by focusing on long-term goals that enhance the happiness principle through balance and harmony with others. Thus, honesty and trust is built not on getting what one wants in a selfish manner, but in the development of pleasure through self-control, intellectual understanding, and by prioritizing the world of non-material over the world of the material. Epicurus warns us to be careful with the obsession for instant profit or material gain at the cost of other more important elements like the values of honesty, team work, self-confidence, reliability, and the legacy we wish to leave.

Outcomes of Objectivity and Subjectivity

It is important to take a look at recurring themes through each theory presented so far as we consider the nature of objective and subjective thinking. In studying these theories, three suggestions come to mind.

First, true ethical behavior begins with ourselves not others. All three theories discuss the importance of weighing individual or subjective analysis either through intellectual reevaluation of individual behavior/thinking or the setting of one’s priorities with the acknowledgement that we must be actively seeking true objectivity or an objective process. Our attitude and individual demeanor/behavior has a significant impact on those around them; perhaps more than possible rules or regulations set up or enacted.

Second, it is important to reevaluate what “true happiness” is. In the last two theories, each philosopher or thinker attempted to come to a real and new understanding of this concept, whether they found such happiness in refined intellectual pleasure or balance/living well. Socrates, Aristotle and Epicurus struggled with this reevaluation conception and did not merely accept the status quo or the general beliefs of those around them. All three believed that left to their own devices, most individuals will not seek out true ethical understanding, nor will they act upon it. Instead, it seems that individuals are misled by many different factors and influences that persuade them to seek out false ends as ethical or not to think about the ramifications of their attitudes and/or decisions. Thus, it is left to insightful and strong critical thinkers to attempt to lead individuals to think through ethical issues and to support and encourage people to understand what true ethical decision-making and therefore, true goodness, happiness or pleasure is.

Third, all three theories emphasize the importance of acknowledging that the focus on true moral thinking in any situation focuses on goals that tend to be long-term with focus on good communication and interaction. In addition, the conversation about how to best determine and preserve essential components of society that lead to happy and moral societies has long been discussed.

Making Sense of the Objective and Subjective Conversation

The examples given from the Ancient Greek world can be assessed for us today. Both objective and subjective thinking have their place. Subjectivism or relativism can be interpreted to be the more productive and truthful interpretation of “good” decision-making but this might be deceiving.

There are many attributes to consider that are favorable, though.

One, different cultural societies seem to have different moral norms.

Two, each culture has morals that seem acceptable to them.

Three, it is hard to determine what is an objective standard for all as that is difficult to assess with one hundred percent assuredness.

Four, it may be the case that one moral code can not be determined as better than any other and it is arrogant of individual cultures or societies to believe that they have a better insight into these matters than another one.

And five, over time, morals seem to change.

What was acceptable behavior or thinking years ago, often seems to fluctuate or change dramatically. On the other hand, there are positive arguments for objectivism or absolutism as well. Objectivism dictates that there must be a certain set of conduct or rules that many subjectivists argue is impossible to find or have knowledge of. On the objectivists’ side, one could argue that there is a peculiar trend, when one “boils” down conceptions or understanding of societies and their norms, that argues that people do in fact conceptualize similar values or virtues and prize them.

A second argument that is strong from the objective standpoint is the assertion that it seems that individuals have innate knowledge and that this knowledge guides us with “natural” and similar reactions or thinking patterns, that dictate similar behavioral patterns. A good example of this is the statement of relativity, itself, which many argue is a universal standard in-and-of-itself.

The third argument for objectivism makes the statement that our language and conceptualization structure reflects a universal process. Terms such as “good” or “right” or “wrong” imply universal conceptions of understanding; not relative constructs. The fourth argument for objectivity lies in relativism’s assumption that different standpoints are equal in value. Though customs differ between societies and people, that does not make peoples’ conceptions true because they believe them. The weakness of human reasoning often lies in the misperceptions that individuals have. Through reason and knowledge accumulation it might be possible to assert Truth in decision-making and find objectivity.

The last argument is the most difficult to argue and lies in how we attain knowledge. All of our knowledge is based on the assumption that information, like in science and math, is true not lies. We can prove what we believe to be true through the methodology of doubt or scientific method with the inference to the best possible outcome. Truth, therefore, is verified through many reasoning procedures. These procedures have proven Truth in metaphysics, epistemology, as well as science, math, and the natural world; the next logical assumption applies to judgment calls or proper decision-making. Thus, a hierarchy of thinking and values must exist and a “better” way of living one’s life and making decisions must exist as well. Both arguments pertaining to this important evaluation principle have value and worth. It is very important that thinkers take into consideration the implications of one’s assumption about morality and values.

The Issue of Free Will vs. Determinism

One other component that we must consider in fully evaluating objective and subjective thinking is the influence of the theories of free will and determinism. By definition, free will is the argument that we have the ability to make choices that influence ourselves and the world around us. Determinism, the contrary argument, espouses the argument that we do not have the ability to make choices that influence ourselves and the world around us. Though these definitions are much more complicated in philosophical study, it is important to take a look at these two approaches to life and the hybrids that exist in peoples’ thinking.

Whether individuals realize it or not, our notions of the world and our place in it, are heavily impacted by the control or perceived control that we have over ourselves and the reality around us. Everyone at some point, has contemplated how much control they have to change their circumstances or dictate their future. At the heart of that thought process is this important thinking dilemma. In a philosophical sense, free will can further be defined as having all choices available at any point in time; while determinism, in its purist philosophical conception, centers on the conception that individuals have no control over those factors that dictate change or the future. The implications of such viewpoints are considerable for business, psychology, law, and even personal relationships.

Let’s take a look at the various “hybrids” that exist and then build on those conceptions to better understand how this interplay of objective and subjective thinking is impacted by such factors. The important thing to remember about the interplay between these beliefs, is that intention and action are important factors to trace and think through. The first approach to this thinking dilemma is libertarianism. Libertarianism is the stance that individuals do, in fact, choose freely on a daily basis and therefore must assume responsibility for those actions. Hard determinism argues that there are no free choices. In the time and space in which we make decisions, other factors like cause and effect and environmental factors (factors outside ourselves), have dictated that it is impossible to argue that we have the freedom to choose anything. Soft determinism espouses the argument of compromise advocating that cause and effect factors do play a part in our choices; thus, determinism does in fact make sense, adhering to arguments that state that we have some freedom, within a limited framework, to make decisions. This theory is best supported by the work of Harry Frankfurt in his text Free Will. He argues that soft determinism or the workings of free will, coincide with layers of desire. The first layer he refers to is first order desires or desires we have no control over. Second order desires, though connected to first order desires, demonstrate free will as he explains that we have control over the reaction or influence of the first order layer of desires. Frankfurt’s theory demonstrates an incorporation of both free will and determinism. The next theory, called free-will-either-way theory, makes the claim that free will exists but that it is important to understand that its existence is tied directly to the fundamental control of determinism. In short, free will exists in direct connection with determinism and that they work together to create reality. The last theory, the counter to this, referred to as no free-will-either-way theory, states that exact opposite. No free will exists as it is directly connected to deterministic factors. Thus, though both conceptions exist, determinism overrides the freedom of “free will” by naturalistic influence. All five of these approaches are incredibly important to consider when evaluating important decisions.

Cause and Effect

It is easy to fall into a framework which acknowledges that we have little or no power to change factors that influence us or our society. Problems emerge from those daily decisions that impact each and everyone of us. In our society, many people argue that they can do very little to change these dilemmas. This belief permeates our society and in reality, is only somewhat true. We are a product of factors such as our background, our environment, our education, our thinking and our beliefs. The issue is whether we have any means in which to work beyond such factors if they, in fact, are leading us to make decisions that continue potentially destructive habits. Will we simply follow in the path that has been directed for us?

The answer to this question is complicated but there must be some acknowledgement that free will must be tempered with determinism, and not left to forms of fatalism. Choices do matter whether they are determined by other factors or not. We are left with assessing, to the best of our ability, the concepts and knowledge given to us, with the understanding that whether we conceive of determinism or free will, we still must progress into the future. The best way to conceptualize this is in leadership terms. If a company has progressed in certain policies that have caused those in power to assess decisions made at that point in reference to that past, regardless of whether those decisions have been productive or not, the determinism of the past decisions have dictated the factors that have produced the current dilemma. Watch Sheena Ivengar discuss the implication of the art of choosing.

Ivengar says that, possessing choices and freedom is a noble goal but she also presents the importance of realizing how life factors influence our decision-making. The free will element found in that determinism, allows for decisions to be made that can align with that series of decisions or reverse against past policies. Awareness, knowledge building, and careful consideration of all factors can help to determine in greater capacity, the root one should take in that particular moment. Adhering to a more subjective standpoint, supports the argument that moral responsibility and decision-making should not be impacted by past events or other factors at all. Thus, what makes sense is a perspective that looks to take responsibility for past decisions where appropriate, and attempts to move forward with the strong desire to improve the situation at hand. This is where ethical study can help.

Thinking Well

The point of looking at the many factors that determine our moral thinking encourages us to be more aware of ourselves, the thinking of those around us, and the conditions in our society that have shaped the world in which we live. Considering the value of thinking about objective and subjective thinking, contemplate this question: how can thinkers better navigate the world around them by being aware of the interaction of objective and subjective thinking and its by-products?

The fact is, many people conceive of the world around them as distant from their reality and therefore the implications of their actions or thoughts, are not important to them, outside of the impact these decisions might have on them directly. This view, as stated earlier, called egoism or in the Ancient Greek world perhaps best termed Sophism, can be a frightening approach to citizenship, decision-making and good thinking. Thinkers must be committed to weighing where relativistic thinking, the acknowledgement that decisions and thinking must be understood as relative to the situation and the context, must be used constructively, while also coming to a clear ideology or understanding of what factors are absolutistic; in that assessment, they must seek out Truth in the midst of such a complicated and troubling dilemma. Absolutism or objectivistic thinking can aid thinkers by reminding them to think through the limits of relative thinking or context by seeking out commonalities in principles, values, virtues, and a conception of the future that will be built on an ideology or series of ideas that are well-thought out and follow good moral evaluation.

Three suggestions from various texts and theories come to mind. The first conceptualization comes from the author Paul Loeb who wrote a book entitled Soul of a Citizen in 2000. In that book, Loeb suggests that the key to solving what he terms the crisis of our citizenry, is to build a society in which thinkers begin to help solve societal problems by determining with greater clarity, what factors of change or relativity are important and what factors should be held unto. Perhaps the greatest factor he thinks we need to start with is honesty.

The second suggestion comes from the work of John Finnis, professor of philosophy at Oxford University, who argues that the key to understanding objectivity and relativity has to do with seven factors that he claims confirm the validity of objective thought and force us to work towards a world of greater connection, responsibility and sympathy towards those around us. He writes that life, knowledge, play, aesthetic experience, sociability, practical reasonableness, and religion, all confirm the importance of our connections with each other and demand that we work towards a world in which we acknowledge our unique contributions to it, but also realize humanity’s undeniable objective tie.

The last theory, espoused by RH Hare, professor of philosophy at the University of Florida, argues that the object of moral thinking in subjective and objective terms must ponder the universal idea of the “right” way to act. That concept of the “right” way, suggests a common conception through reason, of the values that we hold to as a community, as a country and as a world-wide community. Thus, the discussion of objectivity and subjectivity becomes the most important thinking dilemma for individuals to consider in reference to societal and personal “betterment”, regardless of industry, profession, time or location.

What Can We Learn in the End?

How do we become more aware of the interplay of subjectivity and objectivity so that we can be sure that we are creating institutions, communities, a society, and a world that reflects good constructive thinking and decision-making? Every theory that takes a stance on reality, social justice or morality, believes that objectivity is the more significant factor in determining Truth or the right way to solve a certain problem. The premise of their observations and statements infer change; a change that adheres to values, expectations of behavior and appeal to such concepts as justice, fairness, and appropriate treatment of all in our society or world. Though many may disagree on how to solve such problems, the thinking at the root of such conceptions favors a more objective stance with relativistic factors to consider.

This is true even when we must employ the best thinking tool possible–the practice of inference to best explanation. This principle argues that we must use what makes sense by thinking of the possible outcomes while evaluating good reason and building consensus. Thus, we must be prepared to infer through what we think we know the best possible outcome.

Another element to consider in reference to this important question is GE Moore’s theory of organic unity. GE Moore was a prominent thinker in the early twentieth century who taught at Cambridge University. He argued, in simplicity, that moral acts that we decide on should not be limited to pleasure seeking or egoism, but must consist of what we believe to be proper conduct based on the most productive outcome for all involved. His thinking holds objectivity as the basis, arguing that often we do not know what that objective truth might be, but we still must work towards an understanding of what holds us together as human. This is a confirmation, when evaluated, that objectivity is important to focus on.

In conclusion, the issue of objectivity and subjectivity is crucial to good thinking as the process pushes us to be more accurate in determining where subjectivity as value and where objectivity should be valued. When it comes to understanding our world and the people in it, a thinker must be able to carefully and constructively, think through problems with great diligence and respect for all involved. Thinkers acknowledge the different experiences of individuals but also the experiences, factors, thinking processes, or other influences that hold us together as humans. Without the created awareness of both elements, we can not come to understand how unique each situation or person we will be confronted with is, or equally importantly, how each of us is connected by mutual understanding or objective factors that might not be easily apparent.

Watch Terry Fox’s story. Evaluate where the intersection of objective and subjective values are most revealing in this powerful narrative.

References

Arruda, D. (2008, March 30). Terry Fox – ESPN. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjgTlCTluPA

Galef, J. (2016, February). Why you think you’re right — even if you’re wrong. Retrieved

from https://www.ted.com/talks/julia_galef_why_you_think_you_re_right_even_if_you_re_wrong?language=en

Gardner, C. (2009, June 03). Chris Gardner UC Berkeley keynote 2009 (HQ). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?

v=vtYpJzQkx1Y

Gilbert, D. (2005, July). Why we make bad decisions. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/dan_gilbert_researches_happiness?

language=en

Iyengar, S. (2010, July). The art of choosing. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/sheena_iyengar_on_the_art_of_choosing

Loeb, P. R. (2010). Soul of a citizen: Living with conviction in challenging times. New York: St. Martins Griffin.