When you look at your phone or watch in the dark, the display is illuminated electronically. This seems like a small convenience, but in the early parts of the 19th Century outdoor illumination was poor or nonexistent and watches had no battery power for illumination. Seeing a watch face at night was a real problem.

Our understanding of atomic structure and behavior was progressing rapidly in the early part of the Century, revealing the existence of subatomic particles, and new elements, some of which were radioactive. Related technology developed rapidly as well. The radioactive element radium was concentrated from ore and mixed with substances called phosphors into military and consumer products, including paint. These paints could give dials, mechanical gauges, and watches a faint green-blue glow, allowing them to be visible in low light. An industry grew up around these materials and products, employing individuals who would paint these displays by hand.

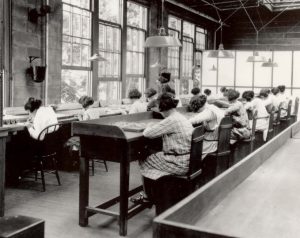

The close work was typically carried out by young women, who used camel hair brushes that had a tendency to lose their fine points quickly. As they painted, these women would often reset the point of their brush with their mouths.

Across the U.S. and Canada thousands did this work. But then negative health effects due to their exposure to radioactivity began to show. Fractured bones, necrosis (deterioration and tissue death) of the jaw, and anemia were associated with the work of the “Radium Girls.” Some of the companies employing these women had deliberately protected their scientific and office workmen from exposure, so this was a scandal as well as a public health disaster. The company’s claims that they were ignorant of the risks were not persuasive.

After multiple deaths, refused insurance claims, resistance by the companies and eventual ruling by the Supreme Court, financial payouts finally got to the sick and their families, and the industry’s reputation was in tatters. Industrial health and safety was changed forever, as was Labor law.