Excavating Archaeological Sites

Jennifer M. Zovar; Cerisa Reynolds; Amanda Wolcott Paskey; and AnnMarie Beasley Cisneros

Learning Objectives

- Describe the process of archaeological excavation

- Explain how different site formation processes affect excavation and interpretation

- Explain the significance of context, provenience, stratigraphy and chronology in archaeological excavation

- Evaluate appropriate excavation strategies for different circumstances

- Explain the ethics of archaeological excavation and collection

I love excavation. I love being outside and getting into the dirt. I love the potential that I might be the first person in 100, 500, or 1000 years to touch a specific object or uncover a feature that tells the story of past human activities. Even on days (or months!) where nothing much is ‘discovered,’ I like the meditative process of slowly scraping through the soil, watching for minute changes in color and texture that may indicate human activity. I enjoy the discipline of plotting a measured, methodical grid across a site and cutting clear, straight unit walls that show the layers of human activity and other natural processes. I like how archaeological excavation unites physical activity with mental analysis in a way that few academic disciplines do. I routinely tell my students that excavation is the most fun part of archaeology (Figure 1).

BUT, with all of that in mind, it is important to begin this chapter on archaeological excavation with three warnings:

- Excavation is only a very small part of what practicing archaeologists actually do – and some archaeologists never go near a trowel. Background research, surveying, mapping, lab work, and analysis are all equally important components of the archaeological process.

- When you excavate an archaeological site, you are destroying it. You can’t excavate the same ground twice – and this means that it is essential to carefully record everything that you do.

- There are important ethical concerns about who has (or should have) authority over sites, artifacts, and landscapes of the past. This includes the power to make decisions about whether archaeological sites should be excavated – and if so, when, and by whom.

We’ll reflect back on these warnings as we move through the chapter. For now, let’s begin with a quick review of what an archaeological site is and how archaeologists go about exploring it.

Defining Archaeological Sites

While archaeological survey takes place over regions and landscapes, excavation takes place at the level of the archaeological site. But just what is a site? Although the term is widely used, its definition is deceptively complicated. Many in the general public assume an archaeological site must include some sort of ancient monumental architecture, but this is not the case. At its most basic, an archaeological site is a place where there is physical evidence of past human activity. A site may be formed because someone lost or threw away one or more objects as they went about their daily activities. Sites may also be created on purpose, through the burial of offerings, caches, or human remains. Finally, a site could be the result of the abandonment of a settlement, structure, or campsite.

Notably, an archaeological site does not always correspond to an area that would have been understood as meaningful to the people who used it. This is because archaeological sites depend on the deposition of material objects or physical changes to the landscape – and not all activities have a physical trace.

For example, when I was growing up, I spent a lot of time in the woods behind my childhood home, building forts or playing hide-and-go-seek with my sister. Other than the odd lost toy, there is no material evidence of that portion of my childhood. However, some old metal tools that were abandoned (but never used) in those same woods are still present. The material evidence leaves a very unbalanced perspective on how this area was used during the 1980s. Think about your own daily lives; which activities leave a material trace, and which do not?

Robert Dunnell (1992) critiqued the concept of ‘site’ in archaeology as being essentially unhelpful to our understanding of the past, noting that sites are defined by the archaeologists who observe them rather than by the people who lived within them. He argued that the term ‘site’ is defective in part because it could lead the archaeologist to overlook how an individual feature fit into a larger archaeological landscape.

Moreover, it’s important to note that an archaeological site may include more than one occupation period, and each occupation may have different boundaries. If I camp by the river and several years later someone builds a factory there, the remains of our two occupations may partially overlap, despite being part of two very different histories. Nevertheless, when an archaeologist records the area, it could be noted as only one site.

Despite these very valid critiques, the term ‘site’ is still standard in archaeological usage, and necessary in cultural resource management in order to be able to legally protect our archaeological heritage. As we excavate, however, we should keep these considerations in mind as we consider how the site was formed. An understanding of site formation processes should affect how we excavate and how we interpret what we find.

Site Formation Processes

Context at a site is critical to understanding archaeological data fully. Archaeologists need to understand the not only the types of artifacts and features at sites they encounter, but also how such remains may have entered the archaeological record, and what happened to them after they are deposited or left behind by humans.

The study of what happens to archaeological remains after burial or deposition is called taphonomy. Taphonomy is important because it is likely that some deposited objects are not in situ – which is Latin for “still,” meaning they are in their original place of deposition – when uncovered by archaeologists. Determining who or what could have caused the item to move from its original depositional location to the current location is important to understanding the complex contextual information presented at the site. For example, a plow in a field could churn the soil, disturbing an unknown archaeological site and redistributing the artifacts.

Site formation processes refer to the way that objects or features become part of the archaeological record through natural processes or as a result of human activity. After a settlement, structure, or campsite is abandoned, the materials left behind may be affected by plant activity, animal activity, human activity, or architectural collapse. For example, the city of Pripyat in Ukraine was abandoned after the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster in 1986, and drone footage from 2013-2016 shows what still remains 20 years after the town was evacuated.

As we excavate, we need to be able to tell if the placement or preservation of different items is due to their original deposition or the result of post-occupation site formation processes. After watching the video of Pripyat, look around the place in which you are currently sitting. If that space were abandoned today, what materials would still be there in 30 years? 300? 3,000? 30,000? What materials would have decomposed? What might be in that space that is not there now? What materials would have been moved around and why? How might decomposition or movement of various items affect future archaeologists’ interpretation of the use of that space?

When archaeologists understand what forces and events could have had an impact on the position of archaeological remains, they are better equipped to answer questions. Such as:

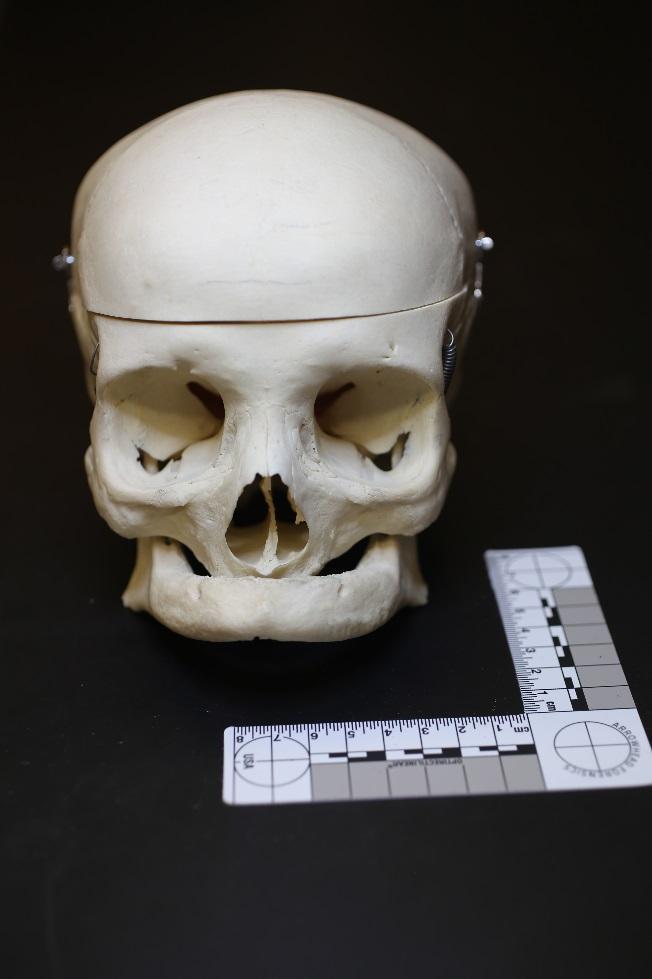

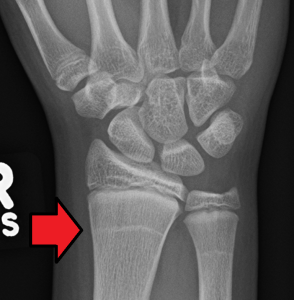

- Are marks on a bone from animal gnawing? Or are the marks signs of early human tool use?

- Was a collection of artifacts was deposited haphazardly? Or were they deposited by a mudslide?

There are many ways for the archaeological record to get mixed up. When archaeologists are excavating and looking at sediments, they are keeping an eye out for something that can alter the integrity of archaeological sites and can impact our stratigraphic profiles. There are a number of different natural formation processes that could affect archaeological interpretation.

A general label you may hear for some natural site formation processes is “bioturbation.” Bioturbation is when any biological organism (rodents, plant or tree roots, etc.) disturb sediments. This can interfere with our ability to understand the archaeological record.

For example, artifacts, ecofacts, and features may be moved as a result of plant growth, especially as roots push through the soil or vines break through architecture. Rodents or other animals may burrow through a site, moving artifacts around, and these burrows may be mistaken for post-holes or other archaeological features. Such floralturbation and faunalturbation can be identified in many abandoned structures (Figure 2).

Other natural site formation processes include cryoturbation (the mixing of soils and associated artifacts due to the freezing and thawing of groundwater), argilliturbation (which occurs in clay soils as they get wet and dry), and graviturbation (which occurs in hilly environments as soils, rocks, and associated artifacts roll downhill).

Identifying natural formation processes and distinguishing them can be really difficult! We can usually see bioturbation because it creates sediments that are of a different color and different texture than the surrounding sediments. In fact, bioturbation is often identifiable because it creates sediments that are much softer than the surrounding sediments. Imagine a mouse digging through 1,000 year old sediments. The older sediments will have become hard and stable over time, whereas the burrow will include organic materials (including leaves, grass, and feces) and will get filled in by sediments falling into the burrow from above and from the walls of the burrow. This creates a different composition (hence the different color) and a different, softer, younger texture. Like many other parts of archaeology, experience will help you see and feel the differences!

Cultural formation processes affect the ultimate presentation of archaeological sites as well. Artifacts from a site may be collected and parts of a site may be reused in a manner different from what was originally intended. Cultural disturbance, like building or farming on top of a previously occupied site, also affects the way the site may appear to archaeologists. By the time a site is recorded, it is often composed primarily of refuse or material that people considered to be no longer useful.

For example, at a site I worked at in Bolivia, a local man shared that as a child one of his jobs had been to collect batanes (grinding stones) that could still be used, and that these would be sold at the market. As a result, archaeologists likely have a significant undercount of batanes that were actually used at the site. Likewise, across the United States, as family farms failed throughout the 20th century, many buildings initially built to house animals were reused for storage or trash, much of which may not be related to the original occupation. In contrast, some of these structures were revitalized and transformed into “rustic” wedding venues. Either form of reuse could confuse future archaeologists interested in the structure, which is why all site formation processes should be considered as we design our excavation strategies.

Excavation Strategies

An excavation begins by deciding where to dig. Archaeologists do not dig haphazardly! Whether we are working in CRM (Cultural Resource Management) or as part of an academic project, we first carefully identify which sites to excavate and where to excavate on a given site. An excavation needs to be planned according to several factors: the goal of the research, available funding, time in the field, and legal/ethical concerns.

Goals, Constraints, and Guidelines

The first thing to consider is the goal of the research. Why are you excavating in the first place? In CRM in the United States, archaeological sites are most often identified in Phase I.This work happens ahead of projects that may impact or destroy any archaeological sites in the project area. You’ll learn more about this process in the chapter on Cultural Resource Management and Archaeology chapter.

Excavation may take place in Phase II or Phase III CRM work. A Phase II excavation is generally small in scale, designed to test the integrity and importance of the archaeological site to see if it is eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. A Phase III excavation is full data recovery, designed to learn as much as possible about the site. CRM projects can answer important questions that can best be answered by excavating a specific site or part of a site that would otherwise be destroyed.

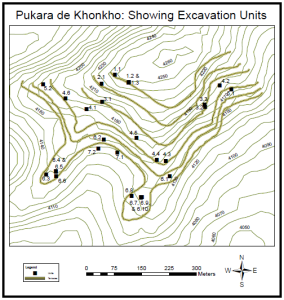

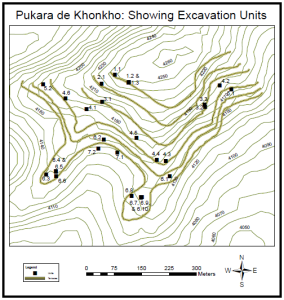

In contrast, an academic project should be guided by a specific, focused research question. What do you hope to learn? An archaeologist who is interested in investigating subsistence strategies would take a very different approach to excavation than one who is researching burial practices, for example. At my own excavations at the site of Pukara de Khonkho in Bolivia, I was most interested in the everyday lives of people at the settlement. As a result, I focused my excavations around the circular domestic structures that were visible on the surface of the site (Figure 3).

Funding is often a limiting factor when it comes to planning an excavation strategy, and this can be true in both CRM and academic contexts. CRM companies will generally bid for projects, trying to balance the need to put forth a competitive bid with the need to earn money to pay the archaeologists and field technicians and also have sufficient funding to effectively follow an appropriate research design. There can sometimes be pressure to complete a project as quickly and cheaply as possible. At the same time, organizations that contract an archaeology firm may have trouble with their own budgetary resources. I once worked on a CRM project that stalled because the development company that had contracted the firm I was working for did not have the funds to continue.

In the academic world, projects are mostly funded through grants. Grants can come from the archaeologist’s own institution, from private granting organizations (e.g. Wenner Gren Foundation, Sigma Xi), from the federal government (e.g. National Science Foundation, Fulbright-Hays), from state or local governments or from non-governmental organizations. Another avenue for funding for an archaeologist working at a college or university is to develop a field school around her research agenda so that student tuition/fees can help fund the work. Because of the constant need for funding, archaeologists often spend considerable time working on grant applications or finding other ways to support their field seasons.

Another limiting factor for any archaeological excavation is time. CRM archaeologists need to complete the work within the scheduled time period and will often have developers urging them to be as fast as possible. Academic archaeologists usually work in the classroom through the fall, winter, and spring, so often end up only being able to do fieldwork in the summer months – or if it is possible to get time off of teaching through a sabbatical or other arrangement. When combined with the need to travel to a site – sometimes in a different country – and navigate paperwork and other bureaucracy before beginning any excavation, this often means that project directors must try to fit in a lot of work into a short time period. This may lead to long days of excavation with minimal time off during the field season. It also means that much of the rest of the year is spent in preparation for what may only be a couple months (or less) of excavation, survey, and other field research.

Last, but certainly not least, it is important to consider the legal and ethical perspective. As discussed in the Cultural Resource Management and Archaeology chapter, excavation in the United States is regulated under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and associated laws, which require coordination with State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPO), Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPO), and other interested parties, including current landowners. You cannot just dig without the appropriate permits! Similar laws exist around the world, and if you are an archaeologist working in another country, it is your responsibility to adhere to any legal requirements surrounding excavation and the treatment/curation of any excavated objects. For example, when I took part in a research project in Bolivia, we needed to follow the protocols of the national government (through the Unidad Nacional de Arqueología) as well as make arrangements with the local community and individual landowners where the excavations would take place. This often required prolonged discussions and negotiations before we could even think about picking up a trowel. As discussed in Archaeological Ethics and World Heritage chapter, such discussions are incredibly important, especially as it concerns descendant communities, and no excavation should ever be conducted without genuine consultation.

Gridding the Site

Once an archaeologist has considered her goals, funding, time, and legal/ethical considerations, it’s time to begin the project! Archaeologists often begin by mapping a grid over the archaeological site. A basic grid helps us keep track of where different archaeological features are found, where excavation units are placed, and how everything relates spatially.

These grids are usually set up using the metric system often on a 1-meter by 1-meter unit (square). The grid scale can be adjusted smaller (25 centimeters by 25 centimeters) or larger (2-meters by 2-meters), depending on what one is looking for. The scale of excavation units for a study is selected based on the types of questions the researcher hopes to address.

When a scale has been established, archaeologists create a grid system based on the coordinates of a fixed point – or datum -which is used for all of their future measurements. The datum typically is a prominent, easy to relocate at a fixed Global Positioning System (GPS) point that is immovable so future researchers who can find it again and make reference to it.

Mapping is an integral part of modern archaeology. We make maps of entire sites and many, many maps of each feature and unit (including each unit’s stratigraphic profiles) while we excavate. Archaeologists make maps by hand, but we also use numerous other technologies that can add dimension or accuracy. We can also use a variety of other techniques to help us record the exact location of features, artifacts, and unit corners. One of the most common tools is a Total Station, which uses a computer and laser to record locations (Figure 4). The data can then be used to create elaborate maps of artifact and unit locations.

Vertical vs. Horizontal Excavation

Depending on the site and the research question, the excavation strategy first considers whether vertical vs. horizontal excavations are necessary. In a vertical excavation, the archaeologists dig deep excavation units, sometimes in a “telephone booth” style. This is useful in highlighting the site’s  Figure 6: Horizontal excavation shows an entire excavation layer. This example from Khonkho Wankane, Bolivia shows the author by the remains of a large structure built along a long compound wall.[/caption]

Figure 6: Horizontal excavation shows an entire excavation layer. This example from Khonkho Wankane, Bolivia shows the author by the remains of a large structure built along a long compound wall.[/caption]

id=”989″]stratigraphy; archaeologists can clearly see the layers of the soil (and the different contexts of site occupation) in the unit walls. Such excavations may also be necessary if the archaeologists are interested in very early time periods that are under deep soil deposits or if they want to better understand the chronology of site occupation. However, because it takes a long time to dig a deep hole, they would excavate fewer excavation units overall, and would only ever uncover small snapshots of the occupation layers they are interested in (Figure 5).

In contrast, a horizontal excavation is designed to bring an entire section or site down to a single occupation layer. This helps archaeologists to see how the different parts of the site were situated in relationship to each other at the time of occupation. This is a great strategy if researchers are following a wall or a building, and want to see it in its entirety. However, if the site was occupied at different times, it prioritizes one occupation over others. Archaeologists would have to dig through (and thus destroy) later occupations to uncover the one they are interested in, and may never get down to earlier occupations (Figure 6).

Sampling Strategies

In almost any context, archaeologists will not be able to excavate an entire site – nor would they want to. Remember, excavation is destruction, so it is always good practice to preserve at least part of the site in situ for future researchers.\

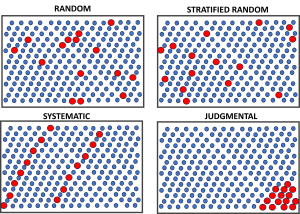

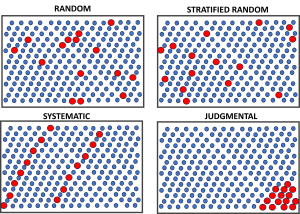

Depending on the specific needs of the project, a sampling strategy for excavation may be random, stratified random, systematic, or judgmental (Figure 7.)

So what is the difference between these four sampling strategies?

A random sample is exactly that. An archaeologist would look at the site grid, number it, and use a random number generator (or similar approach) to select where to place the units. This may be useful if the archaeologist doesn’t know much about the site and is trying to get some basic information.

A stratified random sample is when the archaeologist wants to ensure that she has proportional coverage of different parts of the site. For example, if a site had a clear ritual section and a domestic section, the archaeologist would select a proportional number of units in each area, but the placement of specific units within the area would be random.

A systematic sample would mean excavating a unit in a consistent pattern across the site. This would ensure full, even coverage of the area, but following the pattern strictly also means that the archaeologist could not prioritize areas of the site with a higher probability of producing useful information.

Finally a judgmental sample simply means that the archaeologist would choose where she wants to dig. This is a good way to prioritize specific parts of the site – especially if there is limited time – but has the disadvantage of playing into the researcher’s bias and potentially ignoring the parts of the site that the researcher does not think are important.

In the real world, most excavation strategies use a balance of each approach.

For example, in my work on the site of Pukara de Khonkho, I made the judgmental decision to place the excavation units around previously mapped structures because I was interested in everyday life at the site. I chose a stratified random sample of those structures, making sure to select a proportional number of structures from different parts of the site. (Figure 8).

Excavation Methods

Obviously, there are pros and cons to any excavation strategy, but at a certain point, it’s time to get in the dirt and open the first unit! Through the last few pages, I’ve been referring the archaeological unit, but have not yet defined the term. This is simply the name that is given to the area that is dug for excavation. Archaeological units are usually square, but can be of different sizes depending on the landscape and research question. These squares are usually set up using the metric system often on a 1-meter by 1-meter unit (square). The grid scale can be adjusted smaller (25 centimeters by 25 centimeters) or larger (2-meters by 2-meters), depending on what one is looking for.

The scale of excavation units for a study is selected based on the types of questions the researcher hopes to address. We dig in square shapes in order to maintain some control over the space of excavation and to help with mapping. The units are generally tied into the overall site grid and oriented to the cardinal directions (North/East/South/West). Archaeologists are very careful to dig nice, straight walls that clearly show a profile of the site’s stratigraphy. (Believe me; archaeologists can get very intense about their unit’s walls. If you ever walk too close to the edge of a unit and collapse a wall, you will see real anger!)

Tools of Excavation

The trowel (Figure 9) is probably the most important tool in the archaeologist’s toolkit (quite literally), and is often symbolic of the discipline as a whole. The standard is a pointed masonry trowel, although a complete toolkit will also often include a “margin trowel” with a rectangular blade to help shape the corners of the excavation unit. Marshalltown trowels inspire fairly intense brand loyalty (at least among US archaeologists), as referenced in Flannery’s (1982) classic tongue-in-cheek ode to the field “The Golden Marshalltown.” Field archaeologists tend to have a strong attachment to their personal trowels, and will use the same one for many years. Archaeologists usually keep their trowels sharpened (using a metal file) so that they can more easily cut through small roots during excavation. It is truly a multi-faceted tool, and I’ve even known some archaeologists to practice competitive trowel-throwing events – on breaks, of course. (See The ArchaeoOlympic Games for more suggested events – not to be tried at home!)

However, the trowel is far from the only tool used in excavation. Archaeologists need a compass to orient the unit. Measuring tapes are necessary to make sure the unit is plotted to the correct size. When plotting a 2×2 meter unit, for example, it is possible to ensure that the corners are in the right place by measuring out a 2.83 meter hypotenuse. And you thought you’d never need to use the Pythagorean theorem (Figure 10)!

Nails are used to mark the corners of the unit, and they are wrapped with string, to show the boundaries of the unit wall. An extra length of string is tied to the nail that is chosen as the unit datum (often the highest corner). When a line level is hung from this string to ensure a consistent height, the archaeologist can then measure to the unit floor to keep track of the depth of excavation or to note the location of a specific artifact or feature. (Figure 11).

When it comes to digging, a project may start with a backhoe, a shovel, or a pickaxe to help cut through the thick topsoil and to quickly remove layers of soil that lie over the archaeological context. The choice of tool depends entirely on the type of project and the type of soil. In an environment where archaeologists expect the archaeological materials to appear at a deeper level (for example, when a site is known to lie under plowed farm fields), a backhoe may be used to more quickly remove the upper levels, although a monitor should usually still stand outside and watch to ensure that nothing unexpected is found. A pickaxe may be used if the soil is very compact. On most of the projects I’ve worked on, however, I’ve begun with a flat-edged shovel, sharpened so that it can easily cut through and remove the sod.

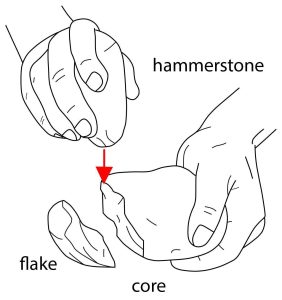

Once the archaeologists are through the thick topsoil and into the levels where they expect to find archaeological materials, they usually switch to hand tools. Trowels are used to scrape dirt into dustpans, which are then dumped into dig buckets. Clippers cut roots/branches that intrude into the excavation unit. Brushes are important to clean artifacts in situ. At times, smaller or more specialized tools can be used in specific contexts. For example, bamboo tools are often used for excavating around bone in order to avoid scratching it.

All dirt from the excavation is put through a screen in order to make sure no artifacts are overlooked. Screens can be different sizes and styles depending on the needs of the excavation. A small hand screen can be carried and used by an individual excavator. A larger rocking sifting screen has two legs that sit on the ground, with the archaeologist holding up the other end; to use this screen, a second archaeologist must be responsible for shoveling and loading the dirt into the screen. While these screens are relatively portable, in longer term excavations, archaeologists might set up larger table screens or hang a screen from a tripod (Figure 12). In the United States, the standard screen size is ¼ inch. This is usually wide enough that the dirt will fall through, but small enough to leave most artifacts/ecofacts behind. Sometimes the screen is of different sizes, depending on the needs of the excavation. For example, since fish bones are often small enough to fall through a standard ¼ inch screen, a sample of soil may be put through a 1/8 inch screen to see if anything is consistently being missed.

How to Dig

Excavation continues in controlled levels. Archaeologists do not dig into the dirt, creating uneven holes. Instead, the trowels are used in a slow scraping motion, taking down the whole unit evenly, a little bit at a time. Excavation pauses at points for notetaking, sketching maps, and to separate the artifacts/ecofacts found at different depths.

When a specific feature is noted (like a pit, a hearth, or a posthole) the feature is excavated separately, in order to keep the items found in that context together and apart from the surrounding soil matrix. This may be useful later in analysis, when archaeologists are trying to date different components of site occupation.

When possible, archaeologists will try to leave an artifact in place until its location can be directly mapped in. Archaeologists are most concerned with context—how an artifact or other type of archaeological data was found in relation to everything else at the archaeological site.

An artifact’s context includes its provenience, exactly where the object was found (horizontally and vertically) in the site; its association in terms of its relationship and positioning with other objects; and the matrix of natural materials such as sediments surrounding and enclosing the object in place.

Archaeologists will measure not only where an artifact or feature is located on a XY axis within the unit itself, but will also measure its depth (as shown in Figure 11) to get a better idea of how it relates to other site artifacts, features and geology. At times, artifacts and features will be recorded using GPS coordinates, but these are not always accurate at the scale archaeologists need in all parts of the world.

Sometimes excavation follows arbitrary (usually 10 cm) levels; other times, archaeologists will attempt to follow the natural levels of the soil. Both techniques provide a vertical control to let the excavators know where any artifacts are coming from. Artificial levels are useful when archaeologists do not know the geology of the area well or when there are not clear distinctions visible in the soil between different occupations or time periods. This avoids mixing of artifacts/ecofacts from different depths, and can be useful in later setting the chronology. When it is possible to clearly distinguish natural layers, however, following these levels can help to distinguish between different deposition events, leading to even better chronological control. As archaeologists dig, they always endeavor to keep the side walls of the unit straight and clean. This helps archaeologists to better identify the site’s stratigraphy, which will later be important in determining chronology. Can you see the shift from the thick grey ash towards the top of the profile to to the darker brown subsoil in the image at left? (Figure 13)

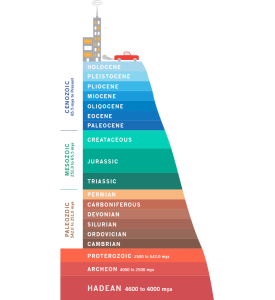

Stratigraphy is the study of the layers of soil within an area. It is an important component of all excavations but particularly critical for vertical excavations. Stratigraphic data assist archaeologists in putting the archaeological record into context; the data provide a relative way to date the site and its contents and can provide some contextual clues about natural formation processes that occurred after the site was abandoned. For stratification to be used scientifically, scientists make two assumptions:

- Soils generally accumulate in layers that are laid down parallel to the Earth’s surface.

- Older soils will typically (but not always) be found below younger soils. Or simply, that the old stuff will be on the bottom. This is also know as the Law of Superposition.

These two assumptions allow archaeologists and others using stratigraphy in their work to understand how the soils accumulated and to use the layers to “tell time.” Vertical excavations move down through sediments and help archaeologists learn more about the site by revealing a site’s stratigraphy! Archaeologists often work with geologists or geoarchaeologists to understand the stratigraphy at a site and what that stratigraphy tells us about the history of the site. Researchers must pay close attention to the context and provenience of the sediments – in addition to the material remains – they are finding and record their observations on numerous forms and through mapping and photographs.

Finally, after the excavation is complete and all notes have been taken, the excavators carefully backfill the units. This helps protect the unexcavated portions of the site. Besides, no one wants a field full of holes!

Recording and Collection

Through it all, no matter where you are working, the most important thing to remember is to take careful notes, as you can see me doing at the site of Pukara de Khonkho (Bolivia) in the image at right (Figure 14). You never get a second chance to excavate an archaeological unit. Once you have removed the soil and the artifacts, it is impossible to put them back exactly the way you found them. In this sense, archaeological excavation differs from other sciences because it is never fully replicable. Through the process of excavation, an archaeologist is destroying the site. If careful notes are not taken at every stage, information is being destroyed — and there is no way to get it back.

How/What to Record

It is one thing to remember that note-taking is important. It is another to figure out exactly what you should record for any given excavation. Different archaeologists have vastly different note-taking styles. Some have a tendency to record literally everything – from the weather, to the way the dew sparkled on the flowers, to their mood that day, to what they had for lunch… If an archaeologist writes too much, especially if it is disorganized, it can be difficult for a later researcher to find the important data amongst her prose. In contrast, you can imagine it is even more frustrating to try to decipher field notes that are too sparse, where the information the researcher needs was never recorded in the first place.

For this reason, most archaeological excavations have standardized forms – or context sheets – that have spaces for the information that the excavators are expected to collect from each level or feature context. The specific items on each form vary from project to project depending on the research design and local idiosyncrasies. However, most include spaces to record the name of the site, the date of excavation, the number of the unit, the level and/or feature number, the depth and size of the context, the color and texture of the soil, the number and type of artifacts, ecofacts, and/or features that were discovered, preliminary interpretations, and any other notes and/or sketches. You can see examples of some context sheets (along with a lesson about how to use them to collect and analyze data) in the “Gabbing about Gabii” Data Story exercise, linked at the end of this chapter.

All collected artifacts and ecofacts are preliminarily put in a bag clearly marked with its provenience. These three-dimensional x, y, z coordinates, including its layer and its specific position relative to the surface (the depth at which it was found) records its former position in situ. As work goes along, a field catalog is created that records everything that was uncovered in the field.

Part of taking good notes also includes collecting good images. Photographs are taken of the archaeological excavation at regular intervals, and some projects supplement with more technological imagery including multispectral imaging or aerial photos from UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles). However, not all imaging requires technology; many archaeological projects also include an archaeological illustrator. Illustrators are skilled at recording the sorts of details that do not show up well in photos, and can also be commissioned to draw site or artifact reconstructions.

Even for archaeologists without an artistic talent, however, it is important to be able to draw basic sketches. These include plot maps of the floors of the different levels of the unit as well as of the profile walls. These drawings should plot the location of relevant features as well as artifacts and ecofacts that were found in situ. Remember, when it comes to analysis, it is absolutely essential to know where an artifact comes from in order to be able to interpret what it means. In fact, I would argue that the most important thing about any excavated artifact is its provenience, the way it relates to other artifacts, features, or local geology.

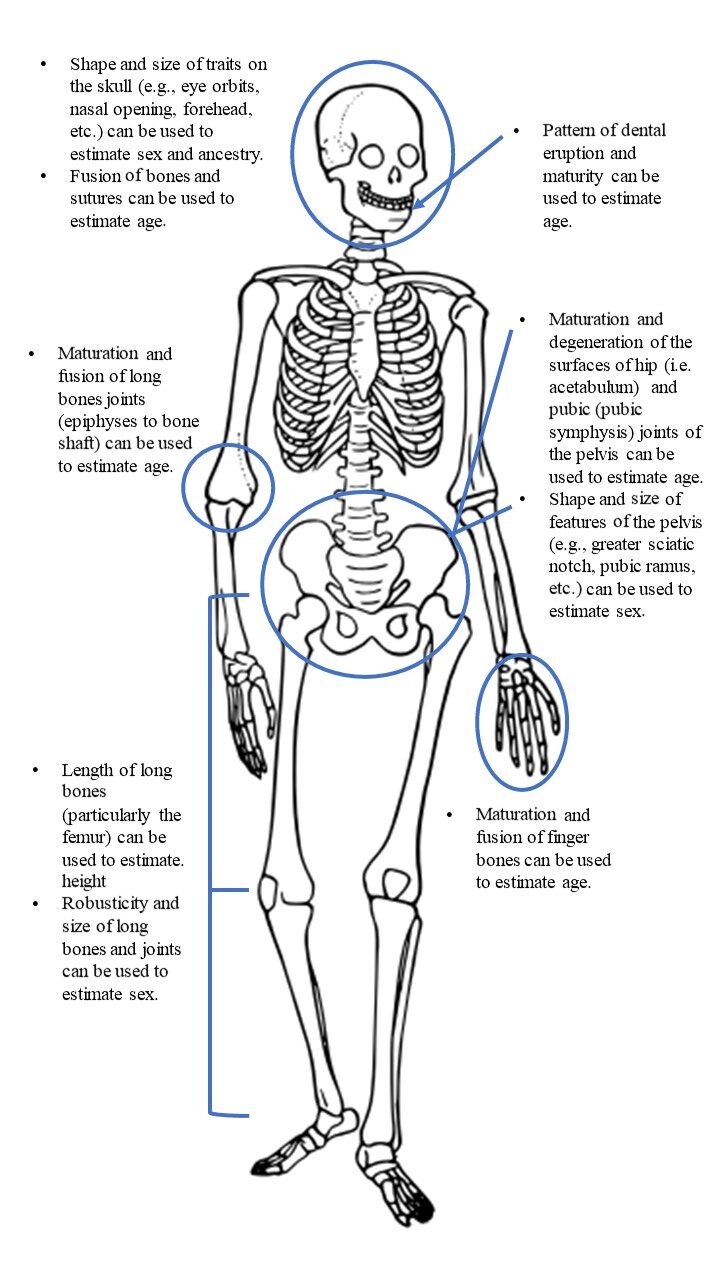

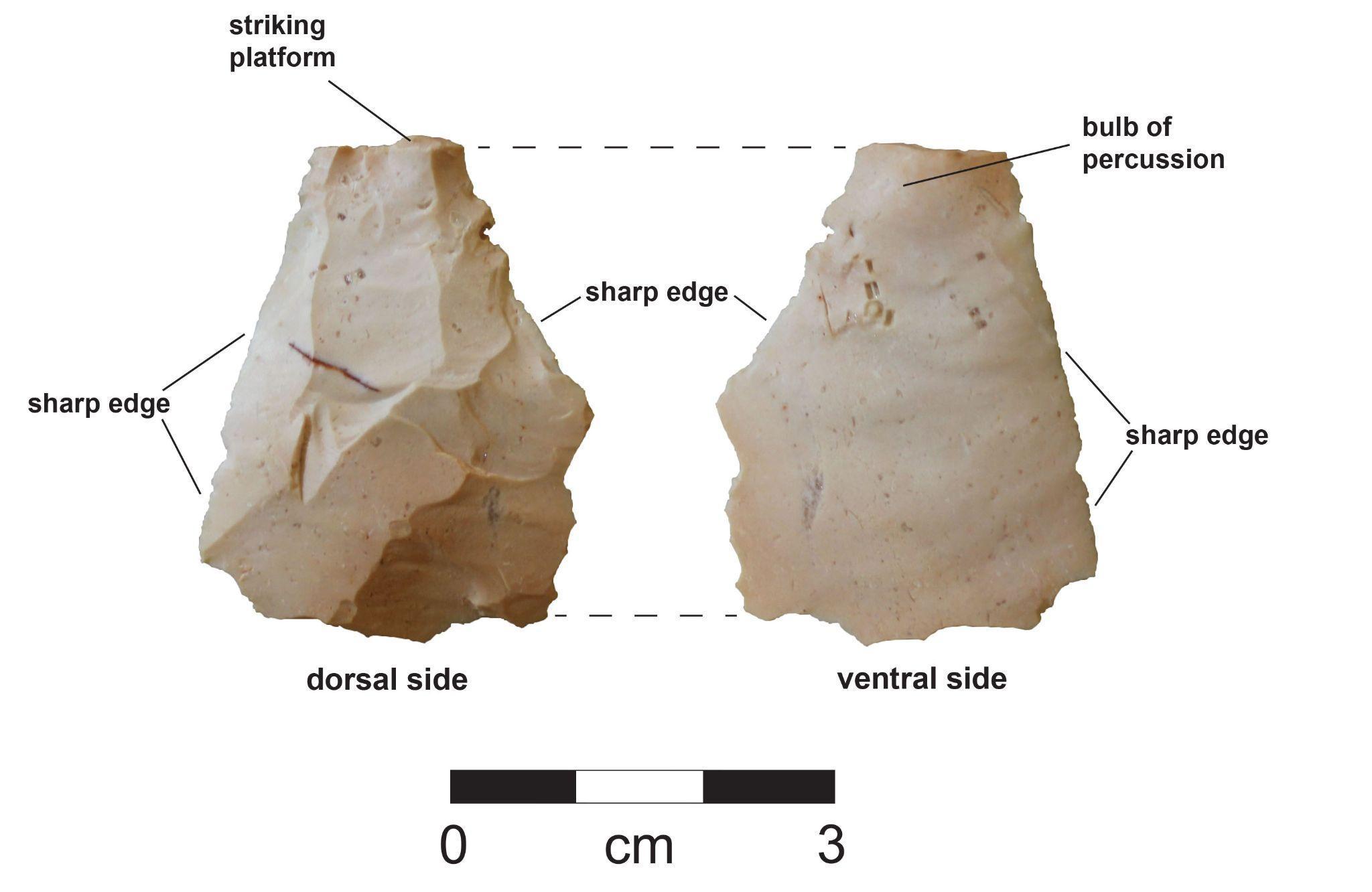

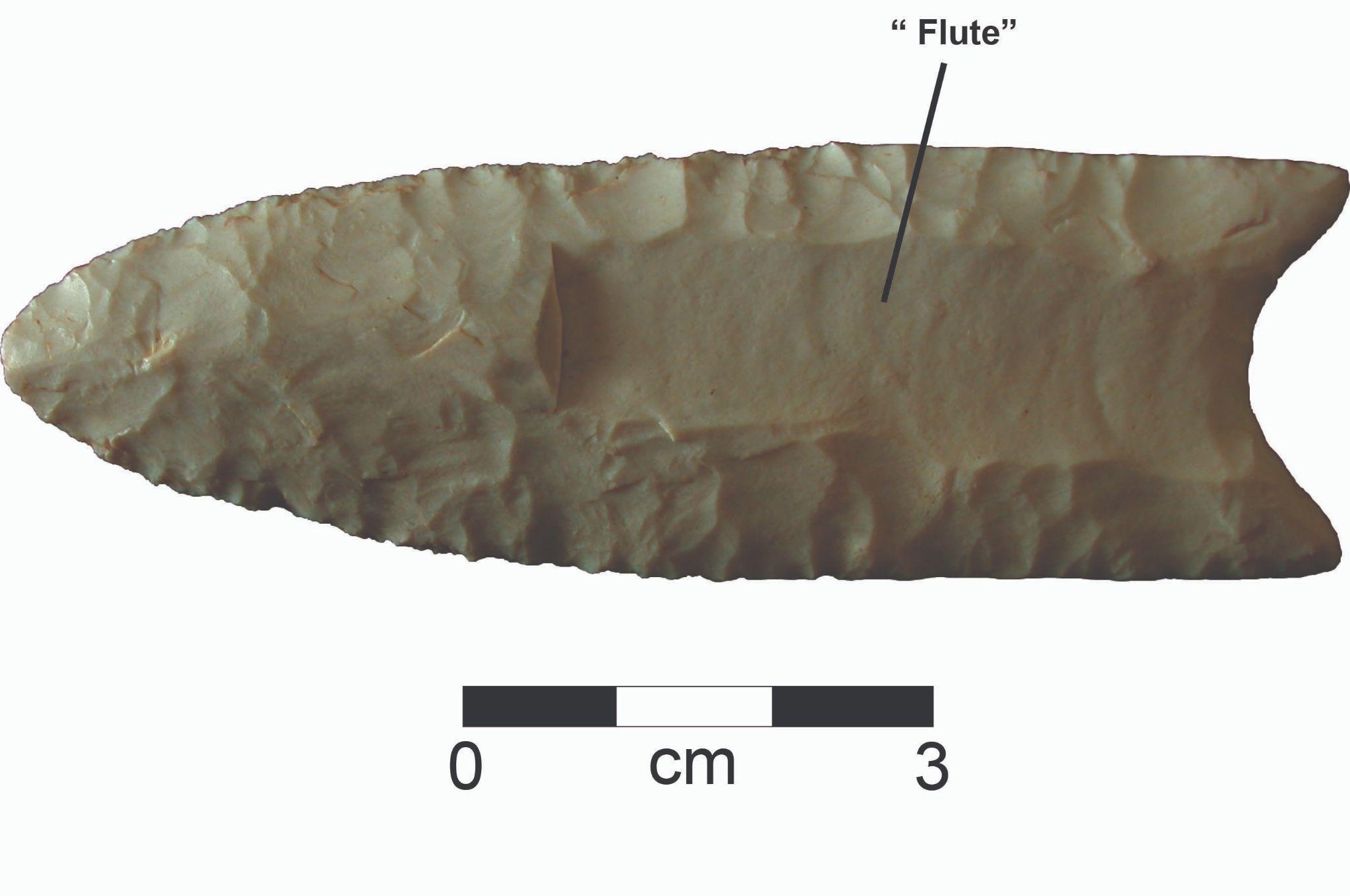

How/What to Collect

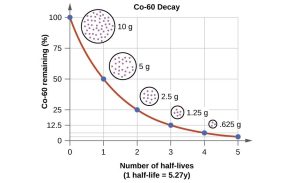

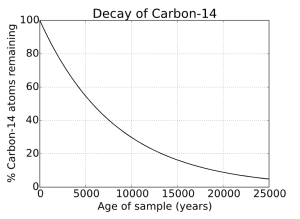

When the notes are complete, it’s time to consider what else you will be taking away from the archaeological site. In most cases, excavators will collect lithics (stone artifacts), ceramics, metals, bone tools, other animal bone, human bone and any other objects identified in the field that were made and/or used by humans. These items will be collected in paper or cloth bags, which are carefully labelled by context so that it will be clear what items were found where when they get into the lab. In addition, burnt wood or other carbon samples are often collected in order to be tested for radiocarbon dating, You’ll learn more about how we test samples in the Dating Methods in Archaeology chapter. Carbon samples should be carefully wrapped in aluminum foil; avoid touching with your hands to reduce the possibility of contamination. In addition, soil samples are often collected from relevant contexts for flotation or other specialized analyses.

Criteria for what should be collected and what should be left behind differ based on the project design and the local archaeological standards. In some cases, it can be hard to tell what is meaningful and what is not when you are in the field. I have been on many projects when objects that looked like lithic debitage in the field turned out to be simple, unmodified rocks once they were cleaned up and analyzed in the lab! In this case, it is generally better to err on the side of caution. An unmodified rock can be thrown out in the lab, but you’ll never get another chance to collect an artifact if you leave it in the field. Archaeologists must also consider where the artifacts will be stored once they are cleaned and analyzed. Good curation is important so that collections can be restudied in the future, but there is a shortage of high-quality facilities available.

In some cases, though, objects cannot – or should not – be collected. Some are too big to be moved from their locations, or they may be part of features (like a part of a structure) that will lose their integrity if removed from the site; preservation may be better in situ than if an item was removed to a lab or repository. In other cases, items should not be removed in accordance with the will of the local or descendant community. There may be spiritual or political reasons that particular items must stay in the location where they were originally found. This is often the case with mortuary or religious contexts. In making these decisions, and indeed through the entire excavation, it is essential to be following clear standards of archaeological ethics.

Ethical Considerations

As discussed in the chapter on Archaeological Ethics and World Heritage, there are various standards of archaeological ethics that govern professional archaeological activities around the world. In the United States, the best known is the Code of Ethics of the Society for American Archaeology, which highlights nine principles: stewardship; accountability; commercialization; public education and outreach; intellectual property; public reporting and publication; records and preservation; training and resources; and safe educational and workplace environments. In this chapter, I draw on this and other ethical codes in considering archaeologists’ responsibilities as we excavate – responsibilities to those with whom we work, to the archaeological record, to descendant communities, and to students and others interested in learning about the past.

Perhaps the first priority is to make sure that the field site is a safe environment for all who work there. This means making sure the excavation is physically safe: don’t dig units that are dangerously deep, and be aware of the potential for dangerous falls or accidents with sharpened trowels or other tools. Every field site should have a first aid kit, and directors should be aware of the nearest health facility – keeping in mind that field research may be far from well-populated areas. Conducting physical labor in a variety of different environments increases the risk for heatstroke, frostbite, allergies, and other environmental hazards. In certain contexts archaeologists should also be prepared for animal attacks, including snake and insect bites. Bacteria and parasites can also be threats, as can hazardous waste, buried chemicals, or even unexploded ordinances that can be encountered during excavation (Poirier & Feder 2001).

In addition, excavation sites should be free from sexual harassment or discrimination. Unfortunately, this has not always been the case. In fact, a recent survey of field-based sciences (including archaeology) found that a majority of female scientists have experienced sexual harassment and discrimination in the field, and sexual assault is also common (Clancy et al. 2014; Meyers et al. 2018). Racial discrimination is also a problem, especially as archaeology – particularly field archaeology – remains a predominately white discipline. See “Why the Whiteness of Archaeology is a Problem” for some specific examples and directions for growth. Until our field sites can be safe for all practitioners, it is difficult to make progress towards stewardship, collaboration, education, or any of our other goals.

Stewardship is the goal to preserve and protect the archaeological record – keeping it out of the hands of looters and other commercial interests. This means excavating judiciously. Since excavation is destruction, archeologists should only dig when we would learn more from the process than we would gain from preserving the site in situ – or when such preservation is impossible due to outside forces like development or climate events. When possible, at least part of the site should be left unexcavated for future archaeologists who may have the advantage of new technologies for analysis and different research questions to investigate. If a site may be threatened by looters, it is essential to not share its exact coordinates publicly unless it is well protected and/or there is a meaningful reason for doing so (e.g. a public outreach campaign). Archaeologists must also care for the objects that are excavated, making sure that they are appropriately curated and stored. In order to discourage commercialization, archaeologists should avoid providing estimates of price for items found on their sites. And it goes without saying that archaeologists should never engage in commercial activity around artifacts that they have personally collected through excavation.

Accountability (to descendant communities and other stakeholders) is key, especially when it comes to human remains or religious sites. Archaeologists do not have an inherent right to excavate anywhere they please; we must coordinate and collaborate with descendent community members and current land-owners in addition to following any state or national-level legislation. While it is a science of the past, all science is conducted for the benefit of living peoples, and the needs of those most closely affiliated with the cultural resources should be prioritized. This means respecting that some sites should never be excavated, and that certain protocols may be necessary in other contexts. For example, in the Aymara community in Bolivia where I have conducted research, it is necessary to prepare a waxt’a (an offering) for the Pachamama (the Aymara ‘Earth Mother’) before any sort of excavation begins. This offering is performed by a yatiri (an Aymara ritual specialist) in accordance with local tradition (Figure 15). This is similar to what is done when the earth is broken for agriculture or construction. The land (and features on the landscape) are living beings in this context – part of the community within which the archaeologists work.

As archaeologists excavate, it’s important to remember our responsibility to share what we have learned, first with descendent communities and other stakeholders, but also with the broader public. We have already discussed the importance of good field notes. However, there is little value in even the most comprehensive field notes if they are simply stored in a researcher’s file cabinet or on her hard drive. For this reason, it is considered an ethical responsibility for archaeologists to publish what they’ve learned. Academic archaeologists generally are most rewarded for publishing in peer-reviewed research journals, but it is also important to share information with the general public – through popular magazines, blogs, TV documentaries, webpages, public outreach events, and/or OER (online educational resources) like this textbook. This also helps to combat pseudoarchaeology, by educating the public and debunking ideas that discriminate against native populations. The chapter on Public Outreach and Archaeology, as well as the chapter titled Understanding Ancient Mysteries will talk more about the importance of communicating factual science-based information.

Finally, archaeologists’ obligation to educate also extends to training new archaeologists in the process of excavation. Since a site can never be excavated twice, good training in excavation is incredibly important. Students should have a safe place to learn without worrying that they might destroy irreplaceable cultural materials. Sometimes, simulated excavations take place in classroom lab or online environments. However, the experience of actually taking part in an archaeological excavation is invaluable, so if you are considering going on in anthropology or archaeology (or even if you just think it sounds like fun!) I would highly recommend attending an archaeological field school. ‘Field schools’ are generally taught over the summer, and provide an opportunity to learn archaeology through hands-on practice, while also earning college credit. There are also many opportunities to volunteer and learn about fieldwork as a citizen scientist.

Conclusion

I began this chapter with three warnings about excavation: there is much more to archaeology than digging; excavation is destruction; and it is essential to consider ethics. After reading this chapter, I hope you can see the importance of each of these caveats. Archaeology is not just about excavation – and in many contexts excavation may even be harmful. That said, when done carefully and ethically – in collaboration and consultation with descendant communities and while taking copious notes – it is an invaluable tool in archaeology’s efforts to learn about the past. And it can also be a lot of fun! I hope you enjoy your time in the field.

- Interactive Digs Exercise: Explore ONE site highlighted on the “Interactive Digs” webpage – interactivedigs.com. Choose whatever site is most interesting to you. Take your time to explore some of the notes, videos, field reports, etc. Be able to briefly summarize what you learned about the site, and compare and contras what you learned with students who explored different sites. You should consider:

- A short description of excavation techniques (e.g. What parts of the site were excavated? How were those decisions made? What tools were used for excavation?)

- A description of any steps being taken to preserve this site and its cultural heritage (e.g. storage/conservation of artifacts, recording/reconstruction of architecture, publication of discoveries/interpretations, etc.)

- A reflection on the role tourism may or may not play at this site (e.g. Is this already a tourist destination? Does it have the potential to draw tourists? What benefits may tourism have to the site? What dangers might tourism pose?)

- Digital Data Stories: Explore the Alexandria Archive Institute’s Digital Data Story “Gabbing about Gabii: Going from Notes to Data to Narrative.” This will give you the experience of working with notes from an excavation to see how archaeologists are able to collect data from excavation and use this data to tell stories about the past.

Note: Parts of this chapter were authored by Jennifer Zovar for a beta version of Traces.

Jennifer Zovar is Associate Professor of Anthropology at Whatcom Community College in Bellingham, WA. Her academic research has focused in the Bolivian Andes, where she investigated an archaeological site that was occupied just before the Inca came into the region (and after the collapse of the earlier Tiwanaku polity.) Despite regularly telling her students that the ceramic analysis chapter of her dissertation was the most boring thing she’s ever written, she is continually inspired by the way that archaeological analysis of the smallest details can lead us to a more complete understanding of the lives of human beings in the past. In addition to her experience in Bolivia, she has also worked on archaeological projects in Guatemala and across the United States. When she is not researching or teaching anthropology, she loves camping and exploring with her kids and a loyal dog named Hank.

Part of this chapter is from Traces by Whatcom Community College and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Parts of this chapter are shared under a CC BY-NC license and were originally authored, remixed, and/or curated by Amanda Wolcott Paskey and AnnMarie Beasley Cisneros (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)). With additional contributions by Cerisa Reynolds

Further Exploration

The ArchaeOlympic Games – https://archaeology.co.uk/articles/news/the-archaeolympic-games.htm

Ethics in Professional Archaeology, Society for American Archaeology – https://www.saa.org/career-practice/ethics-in-professional-archaeology

The Excavation Process: The Tools, a video from Oregon State University’s excavation of the Cooper’s Ferry Site – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9pGbpIPU-Y

Interactive Digs, Archaeological Institute of America – https://www.interactivedigs.com/

Why the Whiteness of Archaeology is a Problem, by William White and Catherine Draycott – https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/archaeology-diversity/

References

Clancy, K., Nelson, R., Rutherford, J., and Hinde, K. (2014). Survey of Academic Field Experiences (SAFE): Trainees Report Harassment and Assault. PLoS ONE 9(7): e102172. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102172

Dunnell, R. C. (1992). The Notion Site. In Space, Time, and Archaeological Landscapes, edited by J. Rossignol & L. Wandsnider, pp. 21-31. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2450-6_2

Flannery, K. (1982). The Golden Marshalltown: A Parable for Archaeology of the 1980’s. American Anthropologist 84(2): 265-278.

Meyers, M. S., Horton, E. T., Boudreaux, E. A., Carmody, S. B., Wright, A. P. & Dekle, V. J. (2018). The context and consequences of sexual harassment in Southeastern archaeology. Advances in Archaeological Practice 6(4):275-287.

Poirier, D. A. & Feder, K. L., eds. (2001). Dangerous Places: Health, Safety, and Archaeology. Bergin & Garvey.

Zovar, J. M. (2012). Post-Collapse Constructions of Community, Memory, and Identity: An Archaeological Analysis of Late Intermediate Period Community Formation in Bolivia’s Desaguadero Valley. [Doctoral dissertation, Vanderbilt University]. Vanderbilt University Institutional Repository. https://etd.library.vanderbilt.edu/etd-08012012-131813

Learning Objectives

-

Describe the importance of public outreach in archaeology

-

Identify methods of public outreach and suggest situations where specific methods may be better suited to a certain archaeological project

Introduction

Every time I tell someone new that I’m an archaeologist, I’m generally met with four different responses:

- “What’s your favorite dinosaur?”

- “A real-life Indiana Jones!”

- “Oh wow, you must find all sorts of cool treasures!”

- “I always wanted to be an archaeologist, but it just wasn’t feasible. I’d love to start the hobby when I retire though!”

These four responses tell me firstly that many people conflate archaeologists and paleontologists—leading to awkward laughing and my admitting that the only dinosaur I know of is the T-Rex. They also tell me that most of what people know about archaeology comes from popular media, namely the Indiana Jones franchise, which harps on this idea of “treasure” rather than cultural significance. This search for treasure then becomes more of a hobby rather than an actual profession, with people assuming archaeologists just dig around in remote areas of the world to find pretty items to line the shelves of museums and private collections with, or to sell. Indeed, shows like American Digger and Indiana Jones do much to emphasize the monetary benefits of artifacts (Pagán 2015), which can lead to the destruction and unlawful looting of archaeological sites. To summarize, it is rare that anyone knows what it is we as archaeologists actually do and how we impact their day-to-day lives with the important research we conduct.

The thing about archaeology is that, even if people don’t totally know what it is, they still tend to associate it as a “cool” profession—so cool, in fact, that it could be a hobby! That said, even if someone were interested enough to try to do their own research on archaeological discoveries, they would not be likely to understand what’s going on. Research papers use so much jargon that sometimes archaeologists with different specialties can’t understand a research article outside of their area of interest (Fagan 2010) so how could a lay person understand what’s going on? Public outreach in this regard becomes a means of translation; we need to communicate with the public in terms they understand because they want to learn, and if we don’t help them, then they either become discouraged and their interest wanes, or they misunderstand the research, which could lead to negative consequences (discussed in detail below).

Furthermore, people are interested in understanding their place in the world, and archaeology can provide them with some of that context. Evolution in particular gains much attraction from the public because people are in search of the healthiest ways to live their lives or are looking for excuses for poor behavior (i.e. violence, sexual aggression and promiscuity; see McCaughey 2008 or Zuk 2013). However, once they grab hold of something—like the Paleo-diet—they tend to run with it, ignoring the fact that science is fluid and discoveries are made every day. For example, although the Paleo-diet considers the ingestion of grain products blasphemous, there’s actually been recent evidence saying that hunter-gatherers of the Paleolithic had been making bread-like products around 14,000 years ago (Zeldovich 2018). Unfortunately for me, the discovery came after I received my Paleo-cookbook for Christmas.

Even more unfortunate is the fact that most evolutionary scientists have done nothing to correct the misconceptions that are so vehemently being passed along; instead, they respond with disgust and condemnation, despite the fact that some practitioners actively reach out to scientists in an attempt to better understand their food practices and make sure they’re being scientifically up-to-date (Chang and Nowell: 2016). Robb Wolf, a prominent member of the Paleo-diet community, has lamented on this very response from anthropologists: “What I have sensed from the anthropology community is an almost… annoyance that upstarts from outside that Guild have the temerity to talk about this stuff and try to apply it in an actionable way… If I could wave a magic wand I’d hope for a bit less prickliness on the part of the medical anthropology community on this topic… If we could get them to understand just how important their understanding of the past is, we might have a much better future’” (Chang and Nowell: 2016: 230).

The thing is, anthropologists know their understanding of the past is important—so why aren’t we leaning into that, especially when others see our studies’ worth? People are interested in what we as archaeologists do and study and it is our obligation to engage them in our work, especially when they reach out to us.

While misconceptions about the field of archaeology and archaeological discoveries themselves are primarily fueled by the media, archaeologists aren’t helping matters. How is anyone outside of the field supposed to know what we do if we do not tell them, much less in language they can understand? It’s necessary that archaeologists begin rigorous public outreach to correct these misinterpretations of our field. In this chapter, I will define public outreach, provide examples of how archaeologists practice public outreach, and explain why it’s important and needs to be done.

Some Considerations

There are many ethical considerations to keep in mind when creating outreach materials—you want to make sure you’re doing things in a “good way.” That being said, I’m going to tell you about what I consider to be two of the most important considerations:

- Keep sensitive cultural material hidden

- You may receive personal anecdotes from community members that you work with, and while they do add a human touch to the “story” you’re trying to tell, they may be too personally or culturally sensitive to share with a wider audience. To accurately deduce what is or is not appropriate to share, collaborate closely with the local community to get their feedback.

- Focusing too heavily on material culture rather than the people who created/used it.

- By focusing solely on the material culture of a site to explain the past, one disconnects the artifacts and the community’s “relationship to their broader environment” (Budwha and Mccreary 2013: 196).

- You risk creating a “spectacle” (Simpson 2011). Reducing people to their material culture relegates the ancestors to the past rather than acknowledging their active participation in the world today. These material objects then act as the face of those who settled there and risk being sensationalized to the extent that they become “native-art-as-usual” (Townsend Gault 2011). Sensationalized objects become static symbols of the past.

Bottom line: Be respectful in what you say, how you say/portray it and collaborate when possible!

The Society for American Archaeology does not have any one definition for public outreach, but rather recognizes it as a collection of methods archaeologists use to engage the public in archaeological research as well as general public awareness ("What Is Public Archaeology?"). Public archaeology can be used synonymously with public outreach.

Public archaeology is often viewed as a subfield of archaeology. However, public outreach in some form or another informs and underlies all archaeology, whether it be in terms of where one’s funding resources come from, where and how one is expected to conduct their fieldwork, how to manage the cultural site, how to treat the archaeological finds, or what kinds of impacts the archaeological research generates (Matsuda 2016:41). All of these instances require communication with some sort of outside source. This means that public outreach can take place before, during, and after the archaeological research is done. Community members can help inform the objectives of an archaeological research project, assist in the actual excavation process beginning as soon as the survey and as late as cleaning and labeling the artifacts, or can be a part of a post-research activity or lecture presented by the researchers. Public outreach can also take place outside of the confines of a particular research project and instead focus on the general understanding of archaeology through hands-on activities in schools or community events. In essence, archaeological public outreach can occur anytime and anywhere in any number of formats.

Public archaeology was once understood to be a means of applying archaeology to the real world via cultural resource management (CRM), contract archaeology, public education, historic preservation, and museology (White et al. 2004). Now there are four different approaches to public archaeology that have been identified:

The educational and public relations approaches are more practice-based, whereas the pluralist and critical approaches are more theoretical.

In particular, the educational approach aims to facilitate people’s learning of the past via archaeological thinking and methods. Archaeological education can occur both on and off-site. Some organizations, like the City of Alexandria’s Archaeology Museum, offer public dig days, in which members of the community can come and participate in an ongoing excavation (White 2019: 37), thus getting hands-on experience in archaeological thinking and methods. For years, the State University of New York at Binghamton’s Undergraduate Anthropology Organization would visit a local elementary school with boxes full of “treasure” strewn in stratified soil, sand, and pebbles, and teach them how to excavate and interpret their findings. These physical experiences not only create strong memories, but also “improves concentration, increases student engagement, and makes learning (and teaching) fun” (Yezzi-Woodley et al. 2019: 50).

The public relations approach works “to increase the recognition, popularity, and support of archaeology in contemporary society” by forming connections between archaeology and individuals and/or social groups (Matsuda 2016: 41-42). This approach parallels the push for archaeological stewardship where the wider community participates in the knowledge production, protection, and reverence of a site, not just archaeologists. Public relations foster stronger connections and responsibility towards sites and knowledge of the past. True knowledge production requires one to ask questions and interpret the evidence beyond uncovering artifacts at a public dig. For example, Science and Social Studies Adventures (SASSA), an organization that “bring[s] archaeology to the classrooms… in order to enhance science and social studies lessons…” took both physics and social studies students to a field that was planned to become a park. The students were taught how to use ground-penetrating radar (GPR) technology to map out the underground features of the property to determine whether or not an excavation would be necessary (Yezzi-Woodley et al. 2019). In this instance, they not only got the hands-on experience of mapping an area with GPR, but also participated in the knowledge production by interpreting that map and determining the future of the site; they now have a sense of responsibility over something tangible and relevant to their community. Similarly, though off-site, Nina Simon of the OF/BY/FOR ALL project encourages participating museums to actively engage their communities in project and exhibit designs to better cater and connect to the wider community (Kluge-Pinsker and Stauffer 2021), while at the same time fostering a sense of responsibility and pride of the past.

The educational and public relations approaches have long been established in archaeology; however, the focus on the pluralist and critical approaches only began to gain traction after the 1990s (Matsuda 2016:42).

The pluralist approach attempts to understand different types of relationships between material culture and different members of the public, which essentially means understanding who your public is and where they’re ideologically coming from (Matsuda 2016:42). Kluge-Pinsker and Stauffer (2021) have taken a pluralist approach to museum visitors. One German study revealed that museum-goers tend to be highly educated, possess high cultural capital, are satisfied with life, and are open to new experiences (Kluge and Pinsker 2021). Closer to home, the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) found that only 9% of museum visitors are from minority populations (Kluge-Pinsker and Stauffer 2021). Furthermore, the AAM’s 2010 demographic study revealed a number of barriers for African American and Latino visitors: historically, museums feel intimidating and exclusionary; the feeling that museums require specialized knowledge and cultivated esthetic taste; a lack of museum-going in one’s childhood; and social networks influence whether or not one chooses museums as a leisure activity (Kluge-Pinsker and Stauffer 2021). With this understanding of how people relate to the past in this particular setting (i.e., museums), cultural institutions can better cater to a wider audience. Specifically, they can choose communication methods more often used by their target audience, offer content that the wider community (especially minority populations) can connect with, provide a welcoming atmosphere, and ensure visually and physically comfortable and pleasing spaces (Kluge-Pinsker and Stauffer 2021).

Finally, the critical approach works to unsettle the interpretation of the past as told by socially dominant groups, who typically have ulterior motives that socially subjugate another group by distorting the telling of the past (Matsuda 2016:42). Evolutionary anthropology has largely taken a critical approach since the end of World War II, when it finally became clear that the scientific support of the social construction of race was detrimental to millions of lives. Until then, it was posited by scientists and laypeople alike that race was a biological fact, and one’s intelligence, capabilities, and worth were determined by their race. Now we know that the variation in human skin color is nothing more than a reflection of millions of years adaptation to changing environments (Echo-Hawk and Zimmerman 2006:471). To totally unsettle the interpretation of an evolutionary past in which it was white people who first settled Europe, a study published in 2007 found that the gene associated with light skin didn’t evolve until 12,000-6,000 years ago (Gibbons 2007: 364; see also Brace et al. 2018 for information on what the first Britons looked like according to “white-hating lefties” [Admin 2018] and Hendrick 2021 for more information on unsettling people’s evolutionary assumptions on race).Both the pluralist and critical approaches view “the public as a subject, which has its own agency and interacts with the past according to its beliefs, interests, and agendas” (Matsuda 2016: 43). These changes are still new for a field rooted in colonialism, so we’re still learning how to effectively conduct public archaeology and outreach.

Community Archaeology

In a general sense, “community archaeology” is the term we use to describe the active participation of non-archaeologists in the archaeological research process, as described above. Ideally, community archaeology includes seven components with which the community is involved in: devising research questions or areas of interest, “setting up a project, field practices, data collection, analysis, storage and dissemination, and public presentation” (Marshall 2002: 211). This means that the community has some level of control of the project at each step (Marshall 2002:212). Arguably one of the most important aspects of community archaeology is that the management of the cultural heritage remains with the community and that research findings are publicly presented (i.e., public outreach is a necessity!) (Marshall 2002:215). Allowing communities to make critical decisions about the direction and implementation of research may seem like a terrifying loss to archaeologists, but it really provides a depth to the research that would’ve otherwise been impossible to achieve (Marshall 2002: 218).

By this point you’re probably wondering who this elusive “community” is. Two types of community tend to show up for these kinds of projects, and often at the same time: people who live locally, either close to or directly at the site, as well as descendants (people who trace their descent from the people who once lived at or near the site in question).

To see community archaeology in action, let’s take a look at Ozette, a late prehistoric/early whaling village at Neah Bay in Washington State (Marshall 2002: 212-213). A mudslide in 1970 exposed substantial house timbers among other organic artifacts (which you may or may not know is absolutely incredible considering organic artifacts typically decompose). This prompted the Makah Tribal Council to contact an archaeologist, and together they set in motion a huge excavation program from 1970 through 1981. The Makah community provided direction throughout the whole project and opened the site to visitors; up to 60,000 people visited each year. Excavated materials were stored and displayed by the Makah community at the newly created Makah Cultural Research Center and a host of publications concerning the site were published. The close collaboration between the archaeologists and Makah residents, the control maintained by Makah people over the project, the retention of the excavated materials by the Makah community for the purposes of preservation, storage, and display, as well as the extensive publications about the site “are very much the goals of community archaeology” (Marshall 2002: 213).

Why Is Public Outreach Important?

The fact is, archaeological sites around the world are in danger. This is important because cultural patrimony (the ongoing cultural importance of an artifact) and heritage tell us who we are and where we come from, which consequently affects our world views and how we act, thus impacting both our present and future. Read the previous chapter on the “Social Impact of Archaeology” for more detail on this particular topic. With a decrease in natural resources, scientists are increasingly looking towards the ocean for the mining of precious and non-precious metals, aggregates extraction, marine engineering, and the production of marine-zone nonrenewable energy, all putting underwater archaeological sites at risk of destruction (Flatman 2009). On the coasts, archaeological sites are threatened by rising sea levels and increasingly powerful storms caused by global warming, among other anthropogenic transformations such as development, mining, and dredging (Fitzpatrick and Braje 2019). War zones see particularly copious amounts of destruction to cultural heritage, either through the creation of defense mechanisms such as trenches, through bombing, or through the intentional destruction of cultural items in an attempt to wipe away one’s nascent culture. Two of the most prominent examples are the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Approximately 2500 objects and sculptures were destroyed, defaced, or stolen from the National Museum of Afghanistan between the years of 1996 and 2001. In Iraq, military bases were established at Babylon and near Ur of the Chaldees, leading to the damage of the archaeological record by way of trench digging, imported gravel, and fuel spills. There was also rampant looting in Iraq (Cunliffe and Curtis 2011).

While it doesn’t get much popular press, national and international cultural sites also face threats due to political decisions. President Trump, recognizing the importance of cultural sites, threatened to bomb 52 Iranian cultural sites “VERY FAST AND VERY HARD” as retribution for 52 American hostages that were taken years prior (Jacobson 2020). In 2017, Trump repealed massive amounts of land in Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears National Monuments that had previously been protected by the Antiquities Act (Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance). This action puts at risk 100,000 archaeological and cultural sites in Bears Ears National Monument alone, including Cedar Mesa which has one of the highest densities of cultural sites in America at several hundred sites per square mile, all to make way for coal mining, irresponsible and damaging motorized recreation, uranium mining, and oil and gas leasing (Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance). This is devastating for the local Native American tribes—including the Hopi tribe, Navajo Nation, Pueblo of Zuni, Ute Indian Tribe, and Ute Mountain Ute tribe—whose ancestral material culture, that provides grounding and pride in their ancestors, is deemed “not unique” or “not of significant scientific or historic interest” and thus disposable by the president (Biber et al 2017). Unfortunately, there are many more threats and sites at risk than here mentioned.

The loss of archaeological sites can cause irreparable damage to communities around the world and thus needs to be stopped. Without archaeological sites, oppressed peoples can be disenfranchised of their history and culture; history can be rewritten by the victor with no one the wiser; and we may never know the truth of where we come from, which could negatively impact the way we think about ourselves (i.e., we may feel we were predestined to live this way, when what evolutionary archaeology shows us so far is that there is no one way to be human). There are many other reasons why archaeology—or the loss thereof—can damage communities, and you should refer to the previous chapter on the “Social Impact of Archaeology” for a better understanding. To exemplify the importance of archaeology generally and thus the need for public outreach, I will provide some instances in which (the public communication of) archaeology can widely impact different communities. I discuss how learning from our past, telling stories, and correcting harmful narratives all contribute to the communities where archaeologists conduct their work.

Learn from Our Past

We can learn a surprising amount of things about humans’ past actions that can help inform how we behave today. In particular, we can look to the past to determine how to create a sustainable future. Between 1987 and 1995 archaeologists of the Garbage Project at the University of Arizona systematically excavated fifteen landfills across North America, in which they found that dating as far back as the 1950s, paper occupied the most landfill space because it was biodegrading very slowly, contrary to what people had once believed (Rathje 2008: 37). Shortly after the excavation reports came out, governments and individual communities began pushing for the curbside recycling that we have come to know and love (Rathje 2008: 37), and now we have any number of recycled paper products at our disposal.

In August 2020, NPR posted an article entitled, “To Manage Wildfire, California Looks to What Tribes Have Known All Along” (Sommer 2020). This article explains how the banning of local Native Americans’ controlled burning practices has led to increased vegetation, which dries out every summer and acts as the kindling for the state’s notorious fires. The state government has recently come to trust in the oral histories of the local tribes and the archaeological record, which argue that the controlled burning of the past had actually been a successful mode of wildfire risk management. According to archaeological finds, controlled burning has been occurring over a vast amount of time and space (Bowman 1998; Heckenberger et al. 2007; Mason 2000). The extent of this evidence provides us with a feasible path forward as we try to reconcile the damage we have since caused through global warming.

Share Untold Stories

Archaeology has a long history of focusing on the stories of rich, able-bodied white men in their prime. This means that the long and equally important histories of ethnic, gendered, and aged minorities are being left out of the stories we tell about the past. This is problematic, because the exclusion of one’s past can lead to subjugation by a dominant group, who often touts their successful past. However, archaeology can also be useful at challenging these problematic assumptions.