Cultural Resource Management and Archaeology: Conserving Heritage

James G. Gibb

- Define Cultural Resource Management (CRM) and explain its role in archaeology

- Describe major pieces of historic preservation legislation and their importance

- Analyze CRM implementation

- Determine how to treat a National Register-eligible site

- Discuss specific career paths in CRM

Overview

Historic preservation laws and regulations, especially since the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966, have contributed to the expansion of archaeology and its role in public discourse on the past. Readers will learn not only about the laws, but also how they are implemented, through a case study. The conditions that drive the archaeological review process are easily understood as is the three-phase approach typical of most archaeological projects. Career prospects, discussed at the end of the chapter, may surprise those unacquainted with the field.

Introduction

For those close to me—grandparents and parents, aunts and uncles, siblings and cousins—family history has been an oral tradition, shared among ourselves at gatherings and with mates—prospective and established—and with close friends. There are scattered family photographs in our respective homes, but photograph albums seldom are produced anymore, and home movies rarely viewed. Mine is a small family—barely two dozen living persons whom I consider family and with whom I share an intimate history. We have little need for objects to remind us of who we are and what we share. When we want to recognize and celebrate our common experience, like many other families, we do so through food and drink: the tray of manicotti, irregularly broken bits of homemade Scottish shortbread, and mason jars of high-octane homemade eggnog (stiffly beaten egg whites, whole milk and cream, lots of rum and more rye, very little sugar and a hint of freshly micro-planed nutmeg).

Writers, pundits, and film-makers often refer to communities—neighborhoods, parishes and counties, states and provinces, nations and the whole of humanity—as families, but they do so metaphorically. Our larger social allegiances lack the intimacy of natal clutches and the breadth of experience is far wider than even a large extended family could ever embrace. The larger and more complex a network of social relations becomes, the more varied the range of experiences of its members, and the greater the need to find a means of expressing connections that are not limited by direct interaction. Never has our need been greater to establish the precedents for those connections: the need to establish and reflect upon a common past, a history.

Consider the 15th- and 16th-century Common Era (CE) mosques of Timbuktu, Mali; the 15th-century city of Chan Chan in Peru, and the 13th- through 16th-century Nan Madol ceremonial center of Eastern Micronesia. Their respective communities created those monuments, in part, as expressions of solidarity and to distinguish themselves from other communities. Today, heritage professionals hope that as World Heritage sites, these and other sites will foster universal identity, enabling us to recognize our common humanity and “family” ties.

There are, apart from other places listed as World Heritage sites, an unbounded—I’m tempted to say infinite—number of sites around the world that may not rise to the level of global importance, but still function as important reminders of shared pasts at the local, regional, and national levels. They also are sources from which scientists extract data with which we can explore the human past and achieve understandings of who we are and how we became the peoples we are at present. Sharing those insights, scientists hope, will foster better citizenship at every level of society, from the remote village to the village of nations, and better decision-making informed by science.

Illumination and common heritage are at the core of cultural resource management, even if many practitioners are immediately drawn to the field because of the lure of discovery: to hold something made centuries earlier and lying unperceived in the earth ever since; to gain novel insight into practices and events previously undocumented, never mind understood; to find in the past those same passions, fears, and optimism we all share today. Archaeology is a science; but it has its share of romance.

Definitions

Cultural resources are material manifestations of a people, past or present, that can be investigated and interpreted in the service of a society, regardless of whether or not a historical link exists between the societies that produced those material manifestations and the society that studies them. The US Department of the Interior, National Park Service (1997) identifies types of cultural resources, examples of which are:

- Landscapes such as Little Big Horn Battlefield where researchers can evaluate competing contemporary explanations (those of Native Americans and the US Army) of what occurred in June 1876, and visitors to the National Historic Monument can experience the setting of this important historical event and reflect on the nation’s troubled past and present in the relations between the peoples and governments of the United States and nations of Native Americans. Devil’s Tower, in Wyoming, is the first place designated as a National Monument under the American Antiquities Act of 1906 for its natural beauty; but it also is a landscape important to a number of Native American groups, a Traditional Cultural Property (TCP) in the language of the law. It isn’t an artifact (an object created by people), nor is it a feature (an artifact such as a hearth or cellar hole that cannot be collected because it is part of the landscape). It is a place significant to the cultural practices and belief systems of one or more groups of people, in this case the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Lakota, Crow, and Shoshone.[1] TCPs are not necessarily landscapes, nor are they exclusively Native American sites.

- Structures such as the Brooklyn Bridge, which links Manhattan with Brooklyn (now a borough of New York, but in 1883 the third largest city in the U.S.) and is a monument to: the nation’s technological prowess; contributions of immigrants to the national culture and economy (the engineer and promoter for the project, John A. Roebling, was a German immigrant); and the emergence of a national culture made possible by developments in the nation’s infrastructure. The Brooklyn Bridge is a National Historic Landmark, a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, and a New York City Landmark, all legal designations that provide protection and eligibility for certain kinds of funding. The Bridge continues to accrue significance as a landmark feature in plays, movies, novels, and the arts.

- Buildings such as the 14th-century CE cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris, France, and George Washington’s 18th-century CE home at Mount Vernon, Virginia, which provide insights into ideas (ecclesiastical and political) and values (aesthetics, spirituality, democracy) that resonate into the present.

- Sites such as the 1620 village of Plymouth, Massachusetts, which long has been investigated archaeologically and interpreted through the non-profit organization Plimoth Plantation. Or an obscure aboriginal site in the uplands of Charles County, Maryland, dating back some 4,000 years and known only to a handful of archaeologists, but not necessarily to the descendants of its Indigenous occupants. There are also multicomponent sites, such as the Nassawango Site in Worcester County, Maryland, which spans from the Paleoindian through the Late Woodland periods – 13,000-2,200 years ago. Consider also a several-block area of downtown Tucson, Arizona, that constituted a “Chinatown” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but which now survives only in archaeological collections, fieldnotes and reports. And the copper-mining sites in the mountains south of Tucson consisting of the remains of tent-platforms, children’s shoes, and enormous numbers of tin food cans left by mining families who emigrated from Europe, Asia, and elsewhere in the Americas in the first half of the 20th century.

- Artifacts—individual objects created and used by people, including documents, such as the United States Declaration of Independence or the Navajo (Diné) Treaty of 1868, provide emotional touchstones with historically meaningful pasts, even if relatively few people have seen these documents in person or touched them. Other artifacts such as the waste flakes produced in making a stone tool or discarded pottery sherds offer less definite links with specific past events and derive their importance through their relationships with other artifacts and remains of houses, shops, mines, temples and the like that once comprised parts of living, vibrant cultures.

Cultural resource management (CRM), as one might expect, is the process by which historically significant landscapes, structures, buildings, sites, and artifacts are identified, assessed, and cared for to ensure their perpetuation for scientific research and personal edification, reflection, and enjoyment. CRM practitioners in the U.S. often refer to the preservation of these tangibles, but conservation may be preferable because it suggests wise managed use of these resources rather than emphasizing the arrest of decay. Best seen as points on a continuum, the choice of one word over the other can have significant policy and practice implications which we can examine; but both terms imply that these manifestations of past cultures also are meaningful parts of living cultures.

For the purposes of this chapter, let’s focus on archaeological sites and standing structures. Artifacts such as stone knives, pottery, and the debris around a blacksmith’s forge are essential elements of an archaeological site, but typically are not considered significant in isolation, only as parts of a site that includes other artifacts and features. Dwellings and bridges could be considered as assemblages of individual artifacts, and even as landscape features, but historic preservationists typically assign them to the class of buildings and structures. Of course, all of these terms are heuristics: they are tools that foster communication and decision-making, but the distinctions are not rigid – they are categories that we, as humans, impose on our surroundings.

Cultural Resource Management: The Process

Imagine a meeting held in one of those windowless conference rooms off the main hallway in a busy government office building. Representatives from one or more government agencies are in attendance as are the permit applicants, their attorney, and their archaeologist. During the course of the discussion, much of it deals with the specifics of a proposed project and how it might have an adverse effect on (we can translate that as damage to) an archaeological site.

Three words or phrases used by each of these parties betray their different interests: while the agency archaeologist and other government representatives refer to “the resource,” the commercial archaeologist working for the permit applicant talks about “the site,” and the applicants may refer to the “damned *?@#$%^&!” in the way of the proposed project that will cost time and money to design around or salvage from.

The attorney, depending on temperament and experience with such matters, will be concerned less with the linguistics and more with the agency’s legal justification for requiring consideration of the project’s effect on the physical manifestation of a past society and how the applicants can best navigate the process with as little expense of time and money as can be negotiated.

The terms used by each of our meeting participants do not indicate mutually exclusive interests: the commercial archaeologist must look to the needs of both the clients and the agency representatives as well as to any particular research interests he or she may have in the site.

The agency representatives have one or more laws, regulations, policies and protocols with which they must comply in protecting resources, but they are not immune to the allure of a rich, new avenue for exploring the past, nor are many permit applicants and their attorneys.

And for all parties, some of these manifestations can be “damned *?@#$%^&!s” because they just aren’t that interesting or appealing, but nevertheless we must adhere to the process of determining their meaningfulness to our society, now and in the future, to ensure transparency, fairness and due respect to the needs of the present and those of the future. Anticipating the diverse and competing needs and interests of the present offers challenges enough for practitioners today; trying to predict those of an undefined future seems hopelessly fruitless. We’ll focus on the present.

And all parties must consider others who aren’t necessarily part of these discussions, but who will make their concerns known during public hearings.

A parcel surveyed by an archaeologist may yield no artifacts or other evidence of past use apart from, say, farming or lumbering. But it may have meaningful associations for a Native American group who traditionally used a portion of the land for individual reflection or group rituals of purification. Enslaved ancestors of an African American community may have congregated for religious services around a small boulder on the property prior to emancipation…a “bush church” (Figure 1).

Determining what is historically significant is a complex process that goes well beyond small meetings in nondescript conference rooms. It involves such questions as: Historically significant to whom? Who has consultation rights? How do we determine if and when one party’s interests carry greater weight in decision-making? There may be no final answers to these and other historic preservation questions. Perhaps there shouldn’t be as the act of asking illuminates who we are and who we want to be.

Let’s leave this meeting and philosophizing for the moment and, through flashback, recount the general and specific events that led to both.

Historic Preservation Legislation

In the U.S., private property is one of the cornerstones of our society, protected by the U.S. Constitution. No interest in private property can be taken without compensation based on a market evaluation of the property and what might be lost by a partial or complete seizing by a government entity.

To be accurate, “rights in land” refers to acquisitions made after the ratification of the U.S. Constitution; the National Museum of the American Indian has a large collection of treaties in which the US government, created by that Constitution, failed to honor Native American claims to the lands now making up the U.S.

Numerous judicial rulings, however, established that different levels of government—local, state, and federal—can impose restrictions on the use of property. Zoning regulations, for example, bar the construction of skyscrapers and pig farms in the midst of most suburban subdivisions to protect the interests of neighboring property owners and to better manage public interests in transportation, sanitation, and other matters.

Without denying new generations of law students the prospect of overturning legal precedent or ambitious politicians the dream of repealing legislation to allow an unencumbered right to do what one wishes with one’s property, let’s accept that historic preservation legislation is firmly based in accepted law and precedent. Let’s further assume that in any given situation the agencies charged with applying the law do so in good faith and full knowledge of what the law allows and what it does not.

General laws protecting the historic and scientific values of resources date to the Antiquities Act of 1906 (Public Law 59–209, 34 Statute 225, 54 U.S.C. §§ 320301 – 320303), signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt and designed to protect historic sites on federal lands from vandalism and theft. The law allows a U.S. president to designate as historic landmarks federal lands and resources without Congressional approval. Subsequent federal laws addressed archaeology on federal lands directly (e.g., the Historic Sites Act of 1935, the Reservoir Salvage Act of 1960) or as one of many considerations in federal undertakings (the Federal Highway Act of 1966, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970). All of these, of course, refer to federal actions, which is to say, undertakings requiring federal lands, permits, or funds.

The landmark federal law, however, is the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which has been amended over the years. Passed in the face of a rapidly expanding American economy, population, and infrastructure, and in the midst of massive urban renewal projects, this law recognized how valuable the past is for the present. History helps make good citizens, an observation made by the country’s third president, Thomas Jefferson, in the larger context of education. And the law established the national government as a leader in historic preservation.

The National Historic Preservation Act (abbreviated NHPA) established State and Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (SHPOs and THPOs) through which federal agencies could coordinate efforts and with which the needs of each state’s citizens could consult on federal undertakings. The NHPA requires federal agencies to ascertain the potential effects of projects on historically significant cultural resources.

For example, will the use of:

-

federal highway funds

-

the expansion of a National Park Service parking lot

-

a permit issued by the US Army Corps of Engineers

destroy a significant building or landscape or archaeological sites?

Buildings and landscapes are relatively easy to deal with because they usually are readily visible, although intensive research may be necessary to understand their historical significance. Most archaeological sites, however, lie below the surface of the ground and cannot be found without systematic survey.

Buildings and landscapes also tend to accrue their own constituencies—individuals and groups committed to their recordation and protection. Most archaeological sites are hidden from view and, therefore, are less likely to have advocates outside of the field of archaeology.

We can witness the demolition of a building or landscape. But without archaeological surveys, sites could remain unidentified and lost to construction and natural disasters without us even knowing of their existence, much less understanding what we have lost by their destruction.

The NHPA assures us that, while we cannot save all archaeological sites, at least we will know what we are losing to federal undertakings because the NHPA requires federal agencies to inventory and assess the value of archaeological sites that may be adversely affected.

Another law of more recent vintage but of nearly as great an influence is the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990. Created largely in response to accumulating grievances of Native Americans over the exhumation of ancestors and funerary objects and other objects significant to Native American and Native Hawaiian groups, NAGPRA imposes conditions on the removal and treatment of human remains and associated objects from Native American and federal lands and held in institutions (largely museums and universities) that are receiving or have received federal funds. In many cases, institutions have been required to inventory such materials in their collections, inform lineal descendants of the peoples whom those materials represent, and return them to the appropriate peoples. Upon their return, materials may be reburied, curated, or otherwise managed as members of the descendant community sees fit.

NAGPRA has had a significant effect not just on the practice of archaeology, but on the ways in which archaeologists see themselves and their work vis-à-vis descendant communities; and not just those of Indigenous communities, but of African American rural communities, Hispanic barrios, and mining towns of largely second- and third-generation European immigrants.

NAGPRA has fostered a sense among scientists, not well developed before the passage of the act, that those outside of the scientific community may also have a claim on the landscapes, structures, buildings, sites, and artifacts of their predecessors. Indeed, the NHPA allows individuals and groups that might not otherwise have standing under general law to be granted consulting party status to proposed federal undertakings, giving them ready access to project-related documents and meetings and allowing them to voice their concerns and have those concerns become part of the public record.

To be clear, these and other federal laws apply only to federal undertakings (actions involving federal lands, permits, or funds) and it is the responsibility of federal agencies to comply with the terms of the NHPA. As anticipated by that law, however, some US municipalities and states have taken their lead from the NHPA, codifying many of the principles and practices established in the NHPA and using two of the more important provisions of the act as historic preservation tools: the standards and guidelines issued and periodically revised by the Secretary of the Department of the Interior (US Department of the Interior, National Park Service 1983) and the National Register of Historic Places, often referred to simply as “the Register” (US Department of the Interior, National Park Service 1997).

The former provides clear guidance on who is qualified to undertake investigations required by the NHPA and the manner in which that work should be done and reported. The National Register establishes guidelines for determining the historical significance of a cultural resource, its eligibility for listing on the Register, and—most importantly from an operational perspective—four criteria for determining significance:

The quality of significance in American history, architecture, archaeology, engineering, and culture is present in districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects that possess integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association, and:

A) that are associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history; or

B) that are associated with the lives of significant persons in our past; or

C) that embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or that represent the work of a master, or that possess high artistic values, or that represent a significant and distinguishable entity the components of which may lack individual distinction; or

D) that have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important in history or prehistory. (US Department of the Interior, National Park Service [1997], https://www.history.nd.gov/hp/nreligibility.html, accessed March 25, 2020)

In practice, Criterion D has been critical in assessing the historical significance of archaeological sites; however, all four criteria should be addressed in any evaluation of a building, landscape, or site for listing on the National Register.

Other criteria stipulate the conditions under which a resource would not be eligible for listing on the Register. Municipal and state agencies devise their own standards and guidelines, and in some cases their own assessments of what is historically significant and what is not. Criterion D is particularly accommodating in this regard: whether a site has “information important in history or prehistory” depends on the scale at which the site is evaluated; e.g., the site of an 1860s rural cheese factory may hold significant information on the history (social, economic, and environmental) of New York State, but remain of relatively little significance to national history. The cheese factory may be eligible for special recognition and protections at the local level, as long as those protections do not interfere with project approval at the federal level.

Enter the Commercial Archaeologist

A number of names have been applied to this kind of work, none of which are satisfactory.

“Cultural Resource Management archaeology” is a misnomer, as consultants like myself typically have little or nothing to do with actually managing resources.

“Contract archaeology” is vague: any work involving funding also involves a contract, whether formal or a verbal agreement, including grant-funded research.

“Compliance archaeology” is closer to the mark, although not all non-academic archaeology is undertaken to assist a permit applicant in complying with a law.

“Commercial archaeology” seems most appropriate in that this kind of archaeological research, while it contributes to larger scientific matters, is conducted as a business; which is to say, one undertakes the work in the expectation of earning a living and it is driven by the needs of a client and not an investigator’s personal research interests. The clever commercial archaeologist satisfies both pecuniary needs and research interests.

As a practicing commercial archaeologist, I am a professional archaeologist operating as a business supplying consulting services to permit applicants. That means I assist clients in complying with federal, state, or local historic preservation laws, particularly the NHPA, the State of Maryland’s version of Section 106 of the NHPA, and the subdivision regulations requiring archaeological review in Maryland’s Anne Arundel, Charles, and Prince George’s counties, as well as preservation regulations in adjacent states.

And that brings us back to how all of this actually works.

A Case Study

Getting back to our meeting in a government office, the participants are discussing an archaeological site. But what site? What kind of site? How did we learn about it? Before we can discuss the fate of this site, we need to learn how we got to the point where it became a subject of discussion.

A case study—the Mill Branch Crossing project—that involves three levels of government suits our needs.

In 2006, Gibraltar Real Estate & Development proposed the construction of a shopping plaza on a 90-acre parcel in Prince George’s County, Maryland, 10 miles or so east of Washington, DC. The project required permits from the US Army Corps of Engineers, the issuance of which was subject to the terms of the NHPA.

Maryland’s State Historic Preservation Office – as a consulting party under the NHPA and the lead historic preservation agency in any state undertaking – became part of the process.

Finally, Prince George’s County had, the year before, enacted its own subdivision regulations that required archaeological review.

Under the NHPA, the Army Corps was required to comply with the law, not the applicant; although the onus for actually doing so fell upon the applicant. While the Prince George County regulation placed responsibility for compliance on the applicant.

The applicant – Gibraltar Real Estate & Development – then commissioned Applied Archaeology and History Associates, Inc., (AAHA). AAHA is a company with more than the minimum qualifications required under Secretary of the Interior guidelines. They would conduct a Phase I archaeological site identification survey.

AAHA conducted a surface reconnaissance of the entire parcel, noting the locations and types of artifacts visible on the plowed surface. Had the fields not been plowed, a large shovel test survey across a grid would have been appropriate. Shovel testing involves archaeologists excavating holes about 16 inches in diameter, extending a foot or more in depth, screening the soil for artifacts, describing the soils, and then backfilling the holes. At Mill Branch, shovel testing was limited to the four archaeological sites found through surface reconnaissance.

The shovel tests were used to collect information on each of the four sites’ depths and soils.

The four sites were registered using the Smithsonian trinomial system:

- 18 represents Maryland as the eighteenth state in alphabetical order

- PR represents Prince George’s County

- 858 represents the next consecutive registration number assigned by the state to the site for the county

The four sites were registered as follows and are described below.

- 18PR858 – a mid-20th-century ranch house

- 18PR859 – possible mill site

- 18PR856 – ceramic, glass and brick debris

- 18PR857 – indications of an 18th-century dwelling

By consensus among the parties who would eventually attend that meeting in the government office building, 18PR858 did not meet the National Register criteria for listing and warranted no further attention.

Site 18PR859, initially characterized as a grist or saw mill site, proved to be a relatively recent flood control or monitoring device that did not meet criteria for historical significance.

Site 18PR856 is a small scatter of ceramic sherds and vessel glass sherds and brick fragments that could be of 18th-century vintage, but appeared to lack information potential, perhaps because the site was lost to plowing and erosion. Considered in isolation, 18PR856 did not meet criteria for listing on the Register.

Site 18PR857 yielded a large number of 18th-century ceramics, glass vessel sherds, and handmade brick indicative of an intact 18th-century dwelling site, likely part of a plantation. Archival research failed to definitively identify the family who lived there, but the site clearly predated the American Revolutionary War. Initial surface finds, coupled with shovel testing, suggested that 18PR857 would meet National Register criteria, and the Phase I report included a recommendation for additional investigation.

The permit applicant commissioned AAHA to conduct a Phase II site examination of 18PR857 to assess the size, depth, integrity of archaeological deposits, and date of occupation. The team excavated 19 square units, each one-meter (approximately three feet) on a side, in those portions of the site with concentrations of artifacts.

The Phase II study confirmed the dates of occupation (18th century) and demonstrated that subsurface features survived intact. That is, several units exposed the tops of postholes, trash-filled pits, and a possible masonry foundation, all potentially rich sources of information that could answer research questions about the Colonial period in this part of Maryland and the greater Chesapeake Bay region.

The Phase II consultants recommended eligibility for listing on the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion D, asserting that 18PR857 could yield important information on how planters in the uplands of coastal Maryland organized their house sites, implemented strategies of food and commodity production, and altered the local ecosystem through intensive cultivation and animal husbandry. The true value of the information would come in comparing the analysis of this site to the results of data analyses conducted on contemporary sites in the region, revealing patterns of both common practices and variability that ramified throughout the subsequent history of the region.

Consensus on the importance of 18PR857, and particularly its meeting Criterion D (but not Criteria A or B—associated with historically significant events or persons—but possibly meeting Criterion C—design and/or construction techniques characteristic of the period), brings us back to the meeting.

Determining Treatment for the National Register-Eligible Site 18PR857

Bringing together the federal, state, and county agency representatives, client, and the client’s attorney and archaeologists is the necessity of discussing one issue: what do we do with 18PR857?

As de facto custodians of our common heritage, agency archaeologists tend to support the preservation of sites for future investigation when questions about the past, methods for exploring it, and tools for collecting data may be more sophisticated.

The permit applicants wanted the site excavated to remove an encumbrance on their planned development, and their attorney supported their interests.

As a commercial archaeologist, I had my own interests to consider, as well as those of both my clients and the agency archaeologists: excavating an entire site would be a large, lucrative contract, and AAHA’s findings indicated that the site would yield useful data for my research into Colonial-era subsistence practices in the Chesapeake region.

The negotiation was protracted and, at times, contentious. Preserving a half-acre site in the middle of a shopping plaza posed expensive engineering and aesthetic design challenges and likely would reduce future profits on the development. In-situ (in place) preservation of the site effectively would remove it from scientific investigation.

The lead agencies could authorize the investigation of the site at some future date, but only portions of the site; there were no protocols in place specifying the conditions and limits of such permission, or even guidelines as to what constitutes “the future.” Insistence on in-situ preservation, in my opinion, also neglected to consider another cultural resource: the funds that the permit applicants would provide for the research, funds that would not be available if the site were preserved in place.

But excavation, especially in this context because the entire site would be excavated, would preclude future investigations by more capable investigators with superior questions, methods, and tools. Of course, scientific questions, methods, and tools develop through application as new data and unforeseen circumstances arise during the course of scientific investigations. Preserving a site does not advance science, and preservation could result in a site remaining unexcavated, essentially eliminating it from research beyond the small amount of data collected in its initial identification and assessment.

Decisions about the fate of 18PR857 did not occur solely within a social vacuum. Public meetings of the county’s Historic Preservation Commission and Planning Board were held. These quasi-governmental entities consist of appointed community members, usually with some connection to urban planning, environmental conservation, historic preservation, history, archaeology, or architectural history. The meetings are staffed by county employees, including an attorney and the county’s historic preservation staff, which includes an archaeologist. Anybody has the right to speak at these meetings and there are procedures and rules for doing so.

There was a great deal of public comment on this project, some of it quite animated; but the concern was not about the archaeological site, the existence of which was unknown prior to its discovery by AAHA. The concern was with development on a farm that was adjacent to a zone in which the county placed restrictions on development and along a highway that already handled traffic loads exceeding capacity.

Preserving the site was a means of stopping the proposed development, or at least scaling it down. As 18PR857 is not a Native American site, there was no basis for consultations with state-recognized Native American groups. There are no federally recognized Native American tribes, or nations, in Maryland. And there is no clear federal process for consulting with Native American groups for most kinds of archaeological sites. Whereas, Native American burial sites always necessitate consultation.

Eventually, the parties reached a consensus: the applicants could commission a Phase III data recovery (also called impact mitigation) at 18PR857, approving a research design that I had prepared. The research design posed several nontrivial questions that could be addressed given the kinds of data already produced by the Phase I and II investigations. It also detailed the field, laboratory and analytical methods that would be used to answer those questions.

Phase III Mitigation

The Phase III work began in November 2019 and the fieldwork ended June 1, 2020. Analyses and a draft report were completed in April 2021. The products include: a detailed report; a large collection of objects, records, and data for use by future scholars; public and academic presentations; a projected book on Colonial era dietary practices and ecological consequences; and, in a small way, this chapter.

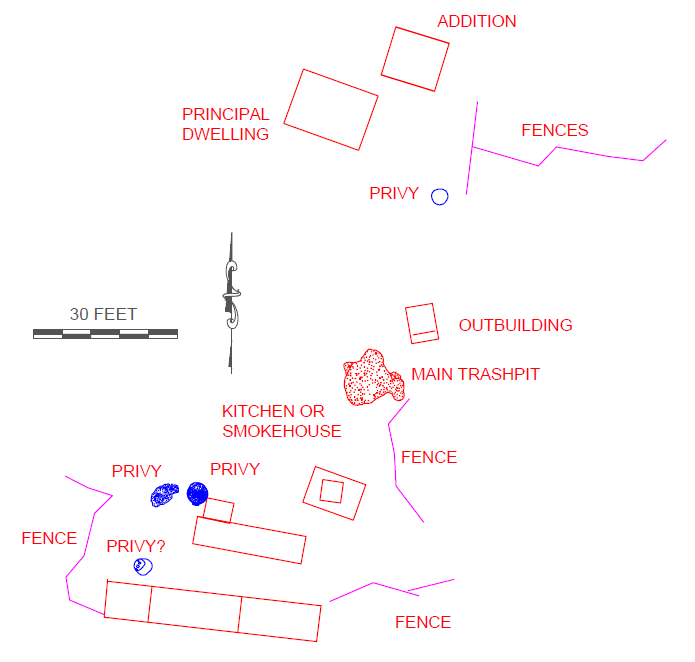

The fieldwork by the crew revealed the remains of a Principal Dwelling (Figure 2), probably a log structure on a partial stone foundation with a brick chimney, occupied by a planter family. This was likely William Goe (a Scotsman), his wife Mary Boyd (daughter of the John and Mary Boyd who settled this parcel in the late 17th century), and their children.

Thirty feet from the dwelling was a privy and another 50 feet to the south were two long, narrow buildings built on wooden posts set into the ground and two privies, one replacing the other. These buildings likely accommodated those people—free or enslaved, or perhaps both—who worked for the Goes. A large pit that appears to have been used by all to discard bones, broken vessels, and other trash occupied the middle ground between planters and workers. Remnants of fencelines also were evident, dividing the houselot along north-south and west-east axes.

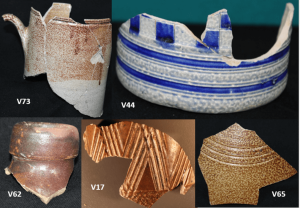

Documents and archaeologically recovered artifacts suggest that the Goes were a family of modest means, occupying 100 acres of Mary’s parents’ land, a 650-acre tract that they called Amptill Grange. Other Boyd children, their spouses, and children occupied their shares of the estate. William and Mary Goe owned some tablewares, including decorated earthenwares and porcelains (Figure 3), but there was no evidence of large, matched dish sets and the crew did not recover any significant evidence of other household furnishings.

Large numbers of nonhuman bone and carbonized plant materials (burning being the primary means by which plants survive archaeologically) were recovered. They revealed a household diet consisting largely of meats from domesticated species (cows, pigs, sheep, and some poultry), a number of hunted species (deer, rabbits, squirrels, mallards, and Canada geese), and locally caught catfish and white perch. There were also remains of oyster and non-local fish (rockfish and porgy). These ocean species were likely procured through others, possibly by way of family-owned businesses in the nearby hamlet of Queen Anne.

The comparison of food remains and architecture with those of other Colonial-era sites in the region suggests that the Goes’ diet was similar to those of other local Colonial households. It differed only in a greater reliance on poultry and wild species along with a reduced dependence on beef cattle and pigs. The analyses continued, particularly to make comparisons with contemporary sites in terms of biological (bones and burned plants) and artifact assemblages. However, the resulting report and collections are the effective end products of the Phase I-III historic preservation process.An archaeological assemblage is the totality of artifacts, ecofacts, human-collected and modified animal and plant remains,* fieldnotes, photographs, catalogues, and drawings from a site.

These are kept together as a collection. This allows for the comparison of one assemblage to assemblages from other sites.

*resulting from food preparation and consumption

To be clear, this process did not begin and end in a single meeting in an office building. It required numerous meetings (both private and public), telephone calls, formal letters, and e-mails over many months. And, of course, it had at its core the scientific processes of research design development (the questions to be asked), methods development (the means of answering those questions), data collection and processing (field and laboratory work), analysis, and report writing.

The goal—achieved, I think—was to balance competing needs and interests and to ensure the best use of 18PR857 as a scientific resource, as an historical touchstone for the region’s citizens—including descendants of the planters and enslaved people and servants—and as a source of material to foster discussions about race relations, the environmental consequences of intensive commercial agriculture, and other matters of current social concern (Gibb 2021). The work at 18PR857 Goe Plantation from its original discovery and testing by the AAHA team to the excavation and analysis of the current team, has proceeded in a thoughtful manner, adapting long-established methods to the specifics of the site.

This work should not be confused with “rescue” or “salvage” archaeology, an ad hoc process of extracting whatever one can from an archaeological site in imminent danger of destruction from natural catastrophes (e.g., forest fires, shoreline erosion) or construction occurring outside of the archaeological review process.

Salvage archaeology typically garners available, but usually insufficient resources, and uses methods adopted expediently, usually in the absence of specific research questions and with minimal or unsystematic documentation in the field. The purpose of salvage often is expressed as recovering material for some unspecified future scholars, without any specific nontrivial questions informing the kinds of materials recovered or the manner of their recovery and recording. Under extraordinary circumstances, archaeologists might choose to salvage a site in the face of imminent destruction, but this is not the manner in which most archaeology is, or should be, done; it does not conform to generally accepted definitions of science.

Careers in CRM Archaeology

Reading about the process above, you might wonder what role you might play in it. Let’s look at the employment prospects first and then consider volunteer participation. Real estate development and engineering are very much part of the process, providing the reason for implementing the process and providing funds and data (e.g., topographic maps of the subject parcels and control points which archaeologists use to accurately locate sites and test units on the surface of the earth). In terms of archaeology, there are three categories of employment across which mobility is possible, but in my experience uncommon. I exclude traditional academic or museum employment from consideration here because jobs in these spheres usually operate outside of CRM; however, university instructors and museum staffs occasionally conduct work in CRM. In doing so, I think, they become, for the duration of such contracts, commercial archaeologists. I also omit the many specialties in archaeology (e.g., faunal analysis palynology, geophysics) as individuals generally are drawn to these after they are engaged in archaeology and most do so within private consultant forms or government agencies and museums.

Agency archaeologists are government employees, generally with advanced academic degrees (master’s, doctorate) in anthropology, archaeology (generally a subdiscipline of anthropology in the US), history, or American studies. They specialize in historic preservation law, but also maintain research interests that, ideally, their position benefits from and which they can satisfy through their official positions. Part-time, seasonal, and contract positions are not uncommon, but most agency archaeologists enjoy fulltime positions with benefits. Most might argue that their compensation is not commensurate with their levels of education and responsibility, especially in comparison with other professionals in government service, but their level of satisfaction in terms of what they contribute to their field may be higher than that enjoyed by professionals in other fields.

Also employed by government agencies, but not typically involved directly in the legal compliance process, are registrars and collections managers. Archaeological registrars oversee the management of data on archaeological sites, collecting data provided by professional and avocational (unpaid) archaeologists. Registering archaeological sites and supplying associated data on artifacts, soil, topography, hydrology, property ownership, prior studies, etc., are critical components of the process of complying with federal, state, and municipal historic preservation laws and ordinances. Data management requires knowledge of the field as well as of relational database management and, increasingly, geographic information systems. Registrars are ideally placed to analyze data from across the jurisdiction of their agency and can achieve a perspective that goes well beyond the site focus to which excavators often succumb. Registering archaeological sites and supplying associated data on artifacts, soil, topography, hydrology, property ownership, prior studies, etc., are critical components of the process of complying with federal, state, and municipal historic preservation laws and ordinances. Data management requires knowledge of the field as well as of relational database management and, increasingly, geographic information systems.

Collections managers have the intimidating job of properly caring for the collections that come to a collections facility (usually lodged within a museum, often at the county or state level). The range of materials could include human remains, food remains (bone, carbonized plant remains, pollen samples), deteriorating iron, decaying wooden boats, stone tools, ceramics, and large quantities of mollusk valves, masonry rubble, and stone tools, to name a few. Some require conservation to ensure that they will not continue to deteriorate. Iron artifacts, for example, typically continue to rust, and at an accelerated rate once excavated and exposed to air. A plastic resealable bag of iron artifacts, even in a facility in which temperature and humidity are tightly controlled, can turn into a bag of dust in a few years if the contents are not stabilized and conserved through desalinization and other processes. Collections managers must have “intellectual control” over the materials in their care, which means they need to know where every item is, even those on loan to other institutions, and their general condition. The position lends itself to all kinds of personal research projects, as well as those demanded by the job.

Finally, there is the commercial archaeologist. Meeting Secretary of the Interior guidelines requires an advanced degree in one of the above-named fields, but education does not—cannot—end with formal classroom work. Unlike academic archaeologists whose primary responsibility typically is teaching undergraduate and graduate students, commercial archaeologists cannot specialize and work in only one research area; e.g., early Colonial-era plantation sites in the Middle Atlantic U.S. or early Holocene Paleoindian sites in the American Plains states. Conducting an archaeological survey of, say, a 100-acre parcel prior to redevelopment could lead to the discovery of Native American deposits dating back five centuries or five millennia, a late 18th-century enslaved peoples’ quarter, a Civil War infantry encampment, a late 19th-century blacksmith shop, and an early 20th-century poultry house.

The competent, productive commercial archaeologist participates in professional conferences, reads widely, continually learns new skills and researches types of sites new to his or her experience, recognizing that all sites and subjects potentially interest somebody and, therefore, require good faith consideration. Commercial archaeologists work from home and for themselves, for small firms operating out of rented houses or storefronts, and out of moderately large and large firms, some operating as divisions within international engineering firms.

Compensation varies depending on responsibilities, experience, and a degree of business acumen, which helps perpetuate the firm, irrespective of size. Those working for larger firms often have the opportunity/onus (depending on one’s perspective) of traveling and working in different regions; smaller operations tend to work within particular regions, states or provinces, if not specific counties, or parishes. Many, like me, work for themselves, aided by staff technicians or contract workers, determining our own schedules and operating as small businesses. A flexible work schedule also allows me to do pro bono work with volunteers and to volunteer on colleagues’ projects. (There is a substantial literature on volunteerism in archaeology, and I have written on the subject of citizen science: volunteer participation in scientific research [Gibb 2018].)

To be clear, the positions that I have sketched are career positions. Absent from the discussion is how one gets to those positions. There are many jobs available in archaeology (such as field technician and lab technician jobs) for those with an undergraduate degree or without any degree whatsoever. Some are seasonal, some might last months, years, or an entire working life. The usual route is to take a field school in archaeology, typically during the summer, through a college or university, and taught by an experienced, reputable archaeologist with the requisite credentials. A field school lasts a minimum of six weeks to be recognized as such. Shorter classes are deemed “field experiences” and are valued, but considered less than a field school which can be an issue if a position opening specifies successful completion of a field school.

There are alternative routes; for example, sustained volunteer work with a reputable organization such as the Smithsonian Institution. Participants could get a wider range of experiences through volunteering, making them more desirable employees. Volunteering also allows greater flexibility for those who cannot afford to commit to six weeks or more and pay additional tuition for a field school.

Regardless of the route, prospective participants should expect, indeed demand, that the principal investigator, or PI (person in charge of the archaeology), and host institution provide a safe environment: safe from outside threats, safe from bigotry, and safe from harassment. The PI and host institution also should meet and preferably exceed the minimum standards for ethical behavior, details of which can be found in the principles espoused by national and international professional organizations (e.g., Society for American Archaeology [www.saa.org/about-archaeology/archaeology-law-ethics]. Accessed March 14, 2021.). The work should have scientific merit and the data collected answer specific research questions, the results of which will be eventually shared through technical reports and publications, as well as through websites, public lectures, and exhibitions.

Every field school—every archaeological investigation—should develop around specific research questions and employ methods suitable for answering those questions. A successful field school experience is a cherished life-long memory, regardless of whether or not it leads to a career in archaeology.

Which of these career positions may be suitable for you, if any, I can’t say. While historically a straight cisgender white man’s field, archaeology benefits from diverse perspectives and there are now as many women as men in the field. Women and transgender persons are increasingly visible in the field and cisgender males likely occupy fewer than half the positions sketched above (that said, cisgender men – specifically white men – still dominate the most prestigious and higher salary levels of employment).

There is room in archaeology, as in every field of human endeavor, for people of all abilities; and most of the frontline archaeological science is done by those of us driven by curiosity, the joy of discovery, and the camaraderie of a team working toward mutually agreed upon goals. Personality, individual and family needs, interests, and other variables play the principal parts in such decisions.

For my part, I quote the writer/actor/producer Mel Brooks: “It’s good to be the king” (History of the World, Part 1, 21st Century Fox, 1981). There is a lot to be said for working for oneself in a field one loves. The joy of approaching each day as an adventure more than balances the occasional financial uncertainty, the frustration with clients and agency colleagues, and the often physically demanding nature of the work. With nearly 50 years of fieldwork behind me, I don’t want to imagine another way of life.

Note: This chapter was adapted from a beta version of Traces.

James G. Gibb majored in anthropology as an undergraduate at Stony Brook University (1978). He earned his master’s degree (1985) and doctorate (1994) at Binghamton University, and a certificate in computer-aided design and drafting at Anne Arundel Community College. He has worked in cultural resource management for 45 years, running his own consulting firm since 1989. Gibb also is the founder and director of the Smithsonian Environmental Archaeology Laboratory (SEAL) at Smithsonian’s Environmental Research Center in Edgewater, Maryland. The SEAL team consists entirely of citizen scientists, volunteers who rather than assist a scientist are themselves the scientists, producing new science individually and in small groups under Gibb’s guidance and presenting results at professional conferences and publishing in professional journals. Gibb lives just outside of Annapolis, Maryland, with his wife Bonnie and three ill-behaved dogs.

Part of this chapter is from Traces by Whatcom Community College and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

Brooks, Mel. (1981). History of the World, Part 1. Motion picture from 21st Century Fox, produced and directed by Mel Brooks.

Gibb, James G. (2018). “Citizen Science: Case studies of public involvement in archaeology at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage, 6(1), 2-30. DOI: 10.1080/20518196.2018.1549815.

Gibb, James G. (2021). A Phase III Archaeological Data Recovery of the Mill Branch Crossing Site (18PR857), Queen Anne District, Prince George’s County, Maryland. Gibb Archaeological Consulting. Submitted to Mill Branch Crossing, LLC., Crofton, Maryland.

Society for American Archaeology. (2021). Archaeology Law and Ethics. Retrieved from http://www.saa.org/about-archaeology/archaeology-law-ethics. Accessed March 14, 2021.

US Department of the Interior, National Park Service. (1997). “How to apply National Register criteria for evaluation.” National Register Bulletin 15. US Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister upload/NRB-15_web508.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2021.

US Department of the Interior, National Park Service. (1983). “Archeology and Historic Preservation: Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines. Professional Qualifications Standards.” ParkNet, National Park Service. Retrieved from https:// www.nps.gov/history/local-law/arch_stnds_9.htm. Accessed 14 March 2021.

- These are Anglicized French and Native American names. Online research will identify the names these peoples apply to themselves in their own languages. ↵

Material manifestations of a people, past or present, that can be investigated and interpreted in the service of a society.

A place significant to the cultural practices and belief systems of one or more groups of people.

The process by which historically significant landscapes, structures, buildings, sites, and artifacts are identified, assessed, and cared for to insure their perpetuation for scientific research and personal edification, reflection, and enjoyment

A place where there is physical or material evidence of past human activity.

An object that was made and used by humans in the past.

The oldest law passed to protect archaeological resources in the United States, designed to protect historic sites on federal lands from vandalism and theft

The landmark federal law protecting US cultural heritage, which governs how cultural resource management is practiced today.

A law passed to protect Indigenous ancestral remains and funerary objects, requiring identification of the lineal descendants of the peoples whom those materials represent, and their return to be reinterred or managed as those peoples deem best.

An archaeologist working in cultural resource management, either as an independent contractor or as an employee of a larger firm. Secretary of the Interior guidelines requires an advanced degree in anthropology or a related field.

The first step in CRM archaeology -- an archaeological site identification survey, designed to see if there are any cultural materials in the impacted area.

The second step in CRM archaeology, designed to evaluate whether or not a recorded site is eligible for inclusion on the National Register.

The third step in CRM archaeology, consisting of data recovery following an approved research design, conducted when an eligible site cannot be preserved.

An ad hoc process of extracting whatever one can from an archaeological site in imminent danger of destruction from natural catastrophes (e.g., forest fires, shoreline erosion) or construction occurring outside of the archaeological review process.

Government employees, generally with advanced academic degrees in anthropology or related fields, who specialize in historic preservation law.

Government employees who oversee the management of data on archaeological sites, collecting data provided by professional and avocational (unpaid) archaeologists.

Archaeologists tasked with properly caring for the collections that come to a collections facility (usually lodged within a museum, often at the county or state level).