Comparing Pseudoarchaeology with Archaeology

David S. Anderson

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish pseudoarchaeological approaches from archaeological approaches

- Analyze the influences that drive people to support pseudoarchaeological claims

The stonemasons of the Inka Empire built some of the most remarkable architecture in human history. The walls at the famous fortress of Saksaywaman stand two to three times as tall as a human being and stretch for hundreds of meters. Even more remarkable than the scope of the walls are the blocks used to build them. Rather than using rectangular blocks, like those used in many architectural traditions around the globe, the blocks of Saksaywaman fit tightly together without mortar and often have five, six, seven, or even more facets. Despite the complicated shapes and the lack of mortar, these blocks still fit neatly together even after having been laid in place more than 500 years ago. More astonishing still is the fact that this level of precision was achieved not with small, relatively light stone blocks, but instead with massive blocks far exceeding what one person, or even a group of people, could easily lift.

In the modern era, many curious travelers have made the pilgrimage to Saksaywaman so that they could marvel at this feat of human engineering. Among these travelers, there have been some doubtful visitors who questioned whether the Inka masons could have truly built these massive walls. After all, construction workers today resort to cranes and other mechanized methods to move similar sized objects. But, if these walls were not built by the Inka, who could have built them? Our doubtful visitors have provided many intriguing, although speculative, answers to this question, ranging from the descendants of the lost continent of Atlantis to visiting space aliens who saw fit to offer humanity a helping hand.

There is a notable problem with these alternative answers. Despite the enormity of the walls at Saksaywaman, archaeologists have been able to answer exactly how the Inka masons achieved this task by examining data from a variety of Inka settlements. Many stone blocks at these other sites exhibit similar patterns of construction, albeit on a less monumental scale. At some of these sites, a few blocks retain small stone protrusions. These protrusions were used in combination with wooden poles to create the simplest of machines, a lever, to raise and lower the blocks until the perfect fit had been achieved (Protzen, 1993). Ideally, these protrusions should have been removed from the blocks when the wall was finished, but the Inka Empire was a relatively short-lived affair and some of the Empire’s building projects were left unfinished. While it may seem remarkable that the blocks of Saksaywaman were lifted with wooden poles, any modern engineer can attest to the remarkable power of levers.

Alternative claims in archaeology, like those forwarded for the walls of Saksaywaman, have enjoyed great popularity over the years. They have been featured as plot points in Hollywood blockbusters such as Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, hit videogames like Assassin’s Creed, and even used as the basis of the Stargate SG-1 television series. They have been found in bestselling books like 1421: The Year China Discovered the World by Gavin Menses and Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock. Topping off the list, cable television has produced an innumerable quantity of infotainment documentaries alleging a variety of spurious claims about the human past. Most influential among these shows has been the Ancient Aliens series produced by the History Channel with a total of 18 seasons aired and more to come. In the face of this rising tide, many archaeologists have sought to speak out against these claims, yet their voices seem to have had little effect.

Some may ask, ‘What is the harm in a few entertaining speculations about the past?’ For one, our collective reputation for human achievement is at stake. By denying the Inka stonemasons credit for their work building the walls of Saksaywaman, we are denying the brilliance and innovative skill of human ancestors. Furthermore, all too often these ‘entertaining speculations’ are made regarding structures built by Indigenous peoples, and as a result these speculations become targeted prejudice questioning the achievements of not all humans, but instead only certain humans.

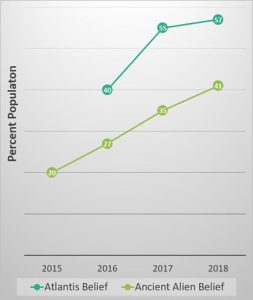

In addition, alternative claims represent an assault on our mental faculties that should concern us greatly. In most cases, alternative claims about archaeology can be debunked with surprisingly little effort. Yet new believers are drawn in on a regular basis. A survey conducted by Chapman University (2018) found that 41% of Americans professed a belief that archaeological evidence supported the claim of ancient alien visitors, that number has doubled since 2015. In the same survey, 57% of Americans claimed Atlantis, or something like it, was also a real place. Both of these claims have been debunked, repeatedly (Colavito, 2005; Kershaw, 2018). The fact that we are so easily seduced by blatantly false claims should be a matter of great concern to us all.

The purpose of this chapter is to engage with these alternative claims in archaeology rather than to brush them aside. Many archaeologists who have attempted to address these issues have focused on debunking claims; that is to say, proving why particular alternative claims about the human past are incorrect. This is important work, but with the continuing rise in popularity of alternative claims it is apparent that debunking is not enough. To combat this misinformation, we need to understand what unites these alternative claims and what the history is behind them. We need to understand the difference between archaeology and pseudoarchaeology.

What is Pseudoarchaeology?

Pseudoarchaeology can be a difficult concept to define. After all, it is a subject that includes topics as diverse as ancient alien contact and claims that Chinese sailors reached the Americas long before Europeans. Pseudoarchaeological claims misrepresent the nature of the archaeological record and methods in order to support predetermined conclusions, e.g., that Atlantis was a real and veritable culture of the ancient world. Yet, when an archaeologist dismisses pseudoarchaeological claims on these grounds, it is often perceived as an authority figure defending establishment opinions. Pseudoarchaeologists have capitalized on dismissals of their claims by painting archaeologists as closed minded and unable to see outside of the confines of their own tradition. Occasionally it has even been alleged that archaeologists are active members in a conspiracy to conceal the true past of humanity. The result has been that pseudoarchaeologists are able to present themselves as a group of outsiders, discriminated against for their claims, but who are nonetheless passionately fighting for the truth. That is a powerful position from which to attract new interested parties.

The characterization of archaeologists as inflexible and blinded by tradition, however, is demonstrably untrue. The very nature of archaeological discourse involves debate, argument, and ultimately revision in the face of new data. Archaeology does not exist without change. For example, archaeologists once insisted that the remains of the Clovis culture represented the earliest human settlers in the Americas. For a period, this claim was insurmountable and anyone who suggested they had found older archaeological remains in the Americas faced skeptical and disbelieving colleagues. Slowly, however, evidence for an earlier occupation mounted with excavations at sites like Monte Verde in Chile and Meadowcroft rock shelter in Pennsylvania, USA. The Clovis First proponents did not give up their position easily, but gradually the weight of evidence convinced the archaeological community that a new understanding of the colonization of the Americas was needed (Meltzer, 2021).

Even more appropriately for this chapter, we can point to the Norse tales that implied Vikings explored the North American coastline. With no physical proof, archaeologists were happy to lump these tales into the category of myth, but when excavations at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada, uncovered clear examples of a Norse settlement site (Ingstad & Ingstad, 2001), archaeologists rapidly changed their opinions on the veracity of these tales. The idea that interpretations of the past can and will change upon the discovery of new data is inherent to modern archaeology.

Yet the dichotomy between archaeology and pseudoarchaeology remains, and we have trouble defining pseudoarchaeology without resorting to an “I’m right and you’re wrong!” mindset. Ultimately, the difference between these two approaches can be best defined through epistemology, a word that I learned (and never again forgot) from reading Ken Feder’s book Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology (2019). Epistemology refers broadly to the study of knowledge, but we can understand this concept more simply as “how you know what you know.” For example, you know that the sun rises in the East not simply because you read it in a book (a secondary source), but because you have watched it happen (a primary source).

Modern archaeologists rely on an epistemology rooted in the scientific method, which requires empirical data analysis and a focus on the context in which data is embedded. An ancient pot is just a pot, but when we know whether it was found in a royal storeroom or alongside a humble hearth, we can learn much more about the people who made it. Archaeological interpretations must be based on the observation of all available data points in relation to their context rather than by looking at a single data point in isolation.

The epistemological difference between archaeology and pseudoarchaeology can be illustrated with a classic example, the Kensington Runestone. In 1898, a Norwegian-American farmer named Olaf Ohman found a slab of stone on his farm outside of Kensington, Minnesota. This stone slab was covered with an inscription written in Medieval Scandinavian runes. Ohman brought the stone into town and its existence was reported in the local paper. As 19th century Minnesota was home to many Norwegian immigrants (an amazing coincidence), it was not long before someone was found who could read this ancestral script. The inscription told the story of a group of wandering Vikings who had made it all the way to Minnesota in the 14th century CE. Advocates for the runestone’s authenticity adopted a pseudoarchaeological epistemology, proclaiming that this one solitary artifact demonstrated the existence of an expansive Viking exploration program into the heart of North America.

The archaeological response has been to ask what other data points are available. As the runestone was found in an empty field, there is no immediate context to compare it to, that is, no other Viking-style artifacts or structures were found. Ultimately, hundreds of archaeological sites have been excavated throughout Minnesota and no other sites show signs of Viking visitors. Instead, only Native American artifacts have been found in contexts that predate the European colonization of North America. If archaeologists have proven anything about human nature it is that humans are messy. Either through deliberate or accidental action, we leave trails of objects behind us wherever we go. No matter how fastidious the Kensington Viking explorers might have been, they would have left something else behind.

In another example, look at the legacy left by European explorer James Cook. Today, the South Pacific is littered with artifacts left behind by Cook and his sailors. The same can be said of other European explorers, including Christopher Columbus, Hernando de Soto, and even the actual Viking explorers who founded the aforementioned village at the L’Anse aux Meadows. The idea that a group of explorers would leave behind a single runestone describing their voyage and nothing else should inspire a great deal of skepticism.

The nail in the coffin of the Kensington Runestone came not from archaeological evidence, since there is not contextual evidence, but from an analysis of the inscription itself. Linguist Henrik Williams has shown that both the runes and the language used in the Kensington Runestone are inconsistent with a 14th century Norse inscription. For example, the term opthagelse farth, meaning “journey of exploration,” does not come into widespread usage until the 16th century. Viking explorers in the 14th century, like those alleged in the Kensington Runestone, are unlikely to have known or used this term (Williams, 2012). Between the lack of supporting archaeological evidence and the critical analysis of the text, most archaeologists believe the Kensington runestone represents the work of 19th century forgers and is thus poor evidence for the existence of Viking explorers in Minnesota.

Pseudoarchaeology is frequently characterized by an epistemology that privileges solitary or anomalous data points over the plethora of consistent and reinforcing data points favored by archaeologists. There is an undeniable glamour in the pseudoarchaeology approach. It fosters the idea that one thoughtful individual may uncover the long-overlooked artifact that will overturn centuries of dry and dusty academic opinion. A traditional archaeological epistemology, however, provides a greater degree of confidence in our interpretations by incorporating not just a single artifact but all of the surrounding artifacts and their associated context.

Thus, pseudoarchaeology is characterized both by its rejection of mainstream archaeology and mainstream archaeology’s rejection of pseudoarchaeology. But, more importantly, pseudoarchaeology is characterized by a privileging of singular data points and ignoring the surrounding context. People’s interest in pseudoarchaeological claims, however, is not based solely on isolated objects. For example, despite the clear and evident problems with the Kensington runestone, many people continue to believe that it is an authentic Viking artifact. Among the most ardent proponents of the stone’s authenticity are the inhabitants of the town of Kensington itself. Pride in our communities and the accomplishments of our ancestors can be powerful motivating factors to accept controversial claims as true. Other pseudoarchaeological claims, however, have more complicated histories and thus more complicated reasons for attracting adherents. Below we will look at two famous pseudoarchaeological claims, where they come from, and why their claims have been so enduring.

The Lost Continent of Atlantis

The lost continent of Atlantis has a particularly seductive charm that has kept the story alive in the subconscious of Westerners for more than 2,000 years. Today, it is a notably popular pseudoarchaeological topic with a new “explorer” claiming to have found the ruins of Atlantis almost every year. Regrettably, these claims of discovery are often picked up by major news networks and run as a break between more serious stories. With approximately half of Americans believing Atlantis could be a real place, it is worth stepping back and looking at where the story of Atlantis originates and why it has such sweeping popularity.

The oldest known account of Atlantis comes from the writing of the Classical Greek philosopher Plato, who described Atlantis in two of his dialogues, Timaeus and Critias. Foremost it is important to keep in mind that Plato was not a historian or a collector of myths, he was a philosopher who wrote dialogues between various characters in order to debate complex moral and ontological problems. Plato’s character of Critias tells us the story of Atlantis, a city that existed 9,000 years ago, beyond the Pillars of Hercules (i.e. the Straits of Gibraltar). The city of Atlantis was located in the center of a continent larger than Libya and Asia combined (i.e. larger than North Africa and Southwest Asia) and was arranged in a series of concentric circles made up of alternating canals and artificial islands, each topped with elaborate architecture and walls of gold and silver. At the center of the city there was a beautiful temple built to honor the god Poseidon. Plato tells us that this magnificent city was the capital of a tyrannical empire bent on invading all of Europe, but the tiny village of Athens (Plato’s hometown) bravely stood fast against the invaders and saved Greece, and all of Europe, from enslavement. After the failed invasion, the God Zeus destroyed Atlantis.

While this description is intriguing, it is clear the story is not literal history. To begin with, as a philosopher Plato regularly incorporated hypothetical examples to illustrate his point, the most famous of which is the allegory of the cave, included in The Republic.

- In Timaeus and Critias, Plato emphasizes the allegorical nature of Atlantis by placing it 9,000 years ago and beyond the Pillars of Hercules; in other words, ‘a long time ago in a place far, far, away.’

- Plato even emphasizes the size of the continent, i.e. larger than both Libya and Asia put together, to make sure the reader new we were talking about a real whopper of a tale.

- Furthermore, Plato’s Atlantis is described, in all the essentials, as a Greek city state as they looked during his lifetime. If the city had existed 9,000 years in the past, tremendous cultural differences would exist between Atlantis and Classical Greece (think for example of the vast differences between contemporary England and England under Roman occupation ca. 2,000 years ago).

- Finally, Plato alleges not just that Atlantis existed 9,000 years ago, but also that Athens also existed this far in the past as well. Despite more then a century of archaeological investigation and study of the Athenian acropolis, no evidence of a 9,000-year-old Athens has ever been found.

Ultimately, Plato’s story of Atlantis was intended as a parable warning the citizens of Athens not to succumb to the dangers of hubris, a sense of overwhelming pride. As the rulers of a great empire and the children of Poseidon, the leaders of Atlantis saw themselves as better than their fellow human beings and even on par with the gods themselves. As a result of this vanity, the gods destroyed Atlantis forever sinking it beneath the ocean. The intent of this story for Plato’s audience, the citizens of Athens, was crystal clear: one should live a humble and pious life always honoring the gods. As residents of an influential city in the Classical Greek world, the Athenians needed to hear this lesson.

Plato’s moral parable remained little known outside of scholarly circles until 1882 when a former Minnesota Congressman, Ignatius Donnelley, published a book titled Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (1882). Donnelley had decided that Plato’s Atlantis was not the moral parable that it appeared to be on the surface, but instead represented a hidden chapter in humanity’s ancient past representing the origin of all Western civilization. To prove his claim, Donnelley turned to the archaeological record. While Atlantis itself was beyond his reach beneath the Atlantic Ocean, he attempted to identify the refugees of the sunken city by looking for similarities in the archaeological record around the world.

The principle on which Donnelley was working has become known as diffusionism among archaeologists. Diffusionism is based on the idea that a particular technology (such as metallurgy) or a stylistic tradition (such as Doric columns) was developed first in one location and then later spread to neighboring regions due to the effectiveness of the technology or the popularity of the style. This is a reasonable explanation and it was widely used by archaeologists in the 19th and early 20th-century (Chapter #). However, Donnelley’s application of the principle made heavy use of the pseudoarchaeology epistemology defined above. He prized singular data points while ignoring the larger context and any data points that did not support his argument.

Based on this approach, Donnelley argued that the archaeological remains of the ancient Egyptian and the ancient Maya cultures in particular showed so many similarities that the only possible explanation was that both cultures had fled Atlantis when it sank beneath the sea.

- Donnelley pointed to superficial similarities such as the fact that both cultures had writing systems and upright stone monuments to prove his point, while ignoring drastic differences in technology, style, language, political structure, and even chronology.

- Also, the Classic Maya cities hit their greatest florescence almost 1,000 years after the last Egyptian Pharaoh sat on his throne.

Despite the obvious problems with his argument, Donnelley’s work found a notable popularity and succeeded in lodging the dream of Atlantis in the public consciousness. Two main reasons can be identified for Donnelley’s success:

- While the existence of ancient Maya culture was widely known in the United States, thanks in large part to the popular travel narratives of diplomat John Stephens, very little was actually known about the Maya. Thus, when Donnelley compared the Egyptians to the Maya, very few people knew enough about the Maya to recognize whether the comparisons were valid.

- The archaeological work of his contemporary, Heinrich Schliemann in the 1870’s, shortly before the publishing of Donnelley’s book, Schliemann was widely hailed as the discoverer of the legendary city of Troy described in the epic poems of Homer.

Dazzled by the discovery of one legendary Greek city, why would the public not be easily swayed by claims of the discovery of a second? Yet despite their mutual origins in Greek literature, there are notable differences between Plato’s philosophical dialogues and Homer’s epic poems. Plato composed his dialogues with a deliberate intent to deliver a moral commentary on his own society, while Homer’s poems represent the final written form of a centuries long oral history tradition very likely inspired by real events. In addition, Schliemann actually excavated an archaeological site; Donnelley’s claims were based purely on speculation concocted from the chair in his office.

The longstanding popularity of Atlantis, however, lies in how Donnelley transformed Plato’s parable. Instead of serving as an example of tyranny and hubris, Donnelley’s Atlantis presented a source for the world’s ancient civilizations, a source not acknowledged by the emerging academic field of archaeology. Donnelly presents us with a classic example of an outsider who believes they alone have uncovered what the professionals have missed, but he was so consumed with proving his predetermined conclusion that he would accept anything as evidence of Atlantis. Rogue outsiders continue to dominate the hunt for Atlantis, and their “success” is trumpeted on infotainment documentaries and YouTube videos in an attempt to claim the establishment will not listen to their evidence. The quest to find Atlantis is less about archaeology and more about our desire to believe a loan outsider can upset centuries of academic research.

Ancient Alien Visitors

The pseudoarchaeological claims of ancient alien visitors have not endured the test of time in the same way as Plato’s Atlantis, but, if possible, these claims have aroused even more ardent supporters. While this topic incorporates a variety of claims, the general argument is that alien beings visited our planet sometime in the ancient past and that the archaeological record includes evidence of these visits. Typically, the artifacts used to make these claims come from numerous time periods and cultures from all over the globe with little attention paid to their original context.

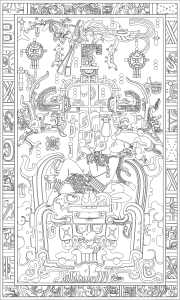

One of the most famous examples of this style of claim comes from the Classic Maya city of Palenque. Pseudoarchaeologists have argued that the carved relief found on the sarcophagus lid of K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, one of the city’s most influential rulers, represents a man flying a rocket ship. Yet, if we compare this image to other examples of contemporaneous Maya art, we find that elements found in the image are commonly used in other carvings and that this image depicts the ruler falling into the underworld (Schele & Miller, 1986). Thus, the mystery is easily solved by examining the complete context rather than looking at the image in isolation.

The story behind the claims of ancient alien visitors is a rather convoluted tale incorporating more than a few colorful characters. Far and away the most influential figure in this story is a man by the name of Erich von Däniken. Von Däniken skyrocketed to global fame when his book Chariots of the Gods? (1968) became an international publishing phenomenon. This book was written with an eye to raising curious questions about the ancient past of the human race, but only hinting at possible answers to those questions (thus offering von Däniken a neat escape route whenever cornered on a particular detail). Despite this evasive writing strategy, the central theme of his book is clear; von Däniken advocates that our planet was visited in the ancient past by alien astronauts and that these aliens influenced the development of our species, both culturally and biologically.

Today, most people are familiar with von Däniken’s claims through the television show Ancient Aliens. One of the driving forces behind the television show is Giorgio Tsoukalos, better known as the ancient alien’s meme guy. Tsoukalos is a protégé of von Däniken and he proposed the initial season of Ancient Aliens in 2010 as an homage to his mentor. After the tremendous success of the first series, the show was renewed and began to incorporate yet more ancient alien claims.

The popularity of von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods? is relatively easy to understand when we consider that it was published in 1968 at the height of the Space Race. The public was never more interested in the stars above and the mysteries they might contain. Chariots of the Gods? brought the stars down to the earth, and von Däniken’s books flew off the shelves. Yet we cannot explain the popularity of the Ancient Aliens television show in the same way as the original book; space is no longer quite so mysterious. To understand the popularity of ancient aliens today, we need to look at how this idea developed over time.

While von Däniken is easily the best-known author of ancient alien claims, he is far from the only proponent or even the originator of the idea. In fact, when writing Chariots of the Gods? he so egregiously copied from earlier pseudoarchaeology authors that he was sued for plagiarism. Close readings of von Däniken’s book have found that he heavily relied on one source in particular, a book titled Moring of the Magicians by Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier (1960). Pauwels and Bergier, however, took a decidedly more spiritual approach to the subject. For them, ancient alien influence was more an issue of spiritualism than of rocket ships.

Pauwels and Bergier claimed their understanding of ancient alien spirits came in part from an obscure occult book known as “The Book of Dzyan.” In Moring of the Magicians, they wrote that “The Book of Dzyan speaks of ‘superior beings of dazzling aspect’ who abandoned the Earth, depriving the impure human race of its knowledge and effacing by disintegration all traces of their passage,” (Pauwels & Bergier, 1960, pp. 154-155) Pauwels and Bergier interpreted these “superior beings” to be alien spirits who, before their sudden departure, had come to Earth to aid humanity’s development. Notably, von Däniken also references “The Book of Dzyan,” describing it as an ancient Tibetan text many thousands of years old.

The existence of such an ancient text is intriguing, and one cannot be faulted for wondering what it might teach us about the human past, but what exactly is “The Book of Dzyan” and why is it not referenced by conventional archaeologists and historians?

The oldest known references to this text come from the esoteric book The Secret Doctrine written by Helena Blavatsky (1888). Blavatsky was born to an upper-class Russian family in 1831 and spent much of her youth traveling throughout Europe absorbing its rich cultural traditions. In the early 1870’s, she immigrated to the United States where she subsequently founded the Theosophical Society. When formed the society’s goals were to investigate the “hidden mysteries of nature and the powers latent in the individual,” (Gomes, 2016, p. 250). The popularity of Theosophy quickly grew as the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution led many people to seek new ways to understand this complex world.

In The Secret Doctrine Blavatsky set out to explain her spiritual perspective, and in so doing she relied heavily on “The Book of Dzyan.” A large portion of The Secret Doctrine is taken up with translations and commentaries on the seven stanzas of “The Book of Dzyan.” In this process, Blavatsky revealed that alien spirits had been visiting our planet and influencing the development of humankind since our earliest days. In particular, she claimed these alien forces led humanity out of Atlantis and Lemuria (another questionable lost continent) and became the earliest rulers of ancient Egypt, the Maya, and other civilizations around the world.

There is, however, a significant problem with Blavatsky’s treatment of this ancient text. To date, no one else has ever seen a copy of the book. Blavatsky claimed to have significant psychic abilities and appears to have gained access to this alleged manuscript by these means rather than possessing a physical copy.

We may ask then, how did this book of questionable origins end up as a significant source in Morning of the Magicians and in turn in von Däniken’s work? For the answer to this question, we are indebted to the research carried out by Jason Colavito for his book The Cult of Alien Gods (2005). In his book, Colavito demonstrates a connection between “The Book of Dzyan,” the pulp fiction horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, and ancient alien theorists.

Lovecraft regularly incorporated elements from the real world into his stories to make them more realistic, and thus more frightening. In particular, he sought out elements from Theosophical beliefs and worked them into his stories as occult mysteries. Thus, we find the following in his story “The Diary of Alonzo Typer” written in 1938:

“The genesis of the world, and of previous worlds, unfolded itself before my eyes, I learned of the city of Shamballa, built by the Lemurians fifty million years ago, yet inviolate still behind its wall of psychic force in the eastern desert. I learned of the Book of Dzyan, whose first six chapters antedate the Earth, and which was old when the lords of Venus came through space in their ships to civilize our planet.”

It should be noted that Lovecraft was not a believer in the occult or ancient aliens for that matter. Lovecraft incorporated these elements into his stories as a deliberately ironic commentary on what he saw as the absurd things people would believe (Poole, 2016). Nevertheless, there exists today a subset of people who believe that Lovecraft was writing truth in the only way that he could, by disguising it as fiction. Among this group were the authors of Morning of the Magicians.

As Colavito uncovered, Pauwels and Bergier were directly responsible for the translation and publication of Lovecraft’s work in France. They also went on to edit a journal devoted in equal parts to Theosophy and Lovecraft, blurring the lines between truth and fiction. Thus, we find a direct chain of thought connecting Blavatsky’s alien spirits who visited Atlantis and von Däniken’s alien astronauts recorded by “The Book of Dzyan.”

The story behind ancient alien contact is not one of archaeological evidence; it is a story of a counterculture movement seeking to find their own path by denying the mainstream. Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society attracted members who felt lost in the industrialized world and wanted a connection with humanity’s roots. Just as today, Ancient Aliens attracts a viewership of those who are dissatisfied with the narrative of human history found in dusty old textbooks. Truth be told, archaeologists in the past have done a poor job communicating the excitement of their discoveries. As a result, many members of the public have turned to more exciting narratives of ancient alien visitors. For this reason, and others, archaeologists today pay careful attention to the field of public archaeology.

The Importance of Understanding Pseudoarchaeology

The massive walls of the Inka fortress at Saksaywaman have been claimed to be the work of both Atlanteans and ancient alien visitors based on the simple assertion that the walls look too complicated for them to have been made by indigenous Inka stonemasons. Yet a review of the archaeological context shows that the Inka regularly and repeatedly built walls of similar composition. The success of pseudoarchaeology is not rooted in the persuasiveness of its evidence, but on a desire for those claims to be true, despite the evidence. The inhabitants of Kensington, Minnesota, want the runestone to be an authentic Viking artifact because it brings great pride of place to Kensington and its modern Nordic descendants. Similarly, pseudoarchaeologists who visit Saksaywaman want to see the glories of a bygone golden age or the mysteries of a denied history in the giant walls before them.

Yet we do not need Atlantis or aliens to accomplish this, the walls of Saksaywaman actually represent a bygone golden age and a denied history. The Inka Empire was a vast and powerful state that ruled over the Andean mountains of South America. The citizens of the empire created great works of art and architecture, built vast cities, and even made historical records using an intricate system of knots and string (Kolata, 2013). We tell school children today that the Inka Empire fell to the guns and steel swords of Francisco Pizarro and a few hundred Spanish soldiers, but this is far from what really happened.

Years before Pizarro landed on the coast of Peru, the entire region experienced a deadly wave of epidemic disease. The earliest European explorers brought both measles and smallpox to the Americas where populations had no inherited resistance to them. These diseases traveled faster than the Europeans themselves, and laid waste to the peoples of the Americas. It is estimated that as many as 60% of the people living in the Inka Empire died from disease, well before they even saw a European. As the epidemic spread, the emperor and his chosen successor both perished and the empire descended into civil war. Only after years of fighting did Pizarro arrive on the shores of Peru to find a once great empire reduced to approximately one-third of its original population and without an agreed upon ruler. Pizarro did not so much conquer the Inka Empire as witness its last dying breath.

Through archaeological research, the achievements of the Inka Empire and its people have been slowly pieced back together, recovering a legacy of human achievement that had been all but lost by introduced disease and colonial conquest. Yet even as those achievements are recovered, they are once again threatened as pseudoarchaeological claims attempt to give credit for the walls of Saksaywaman to someone else. Pseudoarchaeology represents a direct threat to archaeological heritage as it attempts to deny the remarkable achievements of humanity. In particular, a preponderance of pseudoarchaeological claims attempt to deny the achievements of indigenous peoples, thus racial prejudice clearly plays a role in these claims (Halmhofer, 2021). As such, we should not simply dismiss claims of ancient alien contact or Atlantean empires as preposterous but actively oppose them and speak out against them.

Pseudoarchaeology not only represents a threat to our collective heritage, but to our own skills as critical thinkers and observers of the world around us. The past presents real and veritable puzzles, all of which deserve to be examined, poked, and prodded from all directions. Archaeology is in desperate need of new thinkers who have not been steeped in decades of established tradition, but we cannot allow ourselves to be beguiled by the glamour of a pseudoarchaeological epistemology where we pick and choose the points of data that interest us while ignoring everything else. If we want to mitigate the effects of pseudoarchaeology we need to understand why people are attracted to these claims, only then can we begin to save the legacy of the stonemasons who built the walls of Saksaywaman.

Further Exploration

- Card, J. J., & Anderson, D. S. (Eds.). (2016). Lost City, Found Pyramid: Understanding Alternative archaeologies and Pseudoscientific Practices. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Colavito, J. (2005). The Cult of Alien Gods: H. P. Lovecraft and Extraterrestrial Pop Culture. Amherst: Prometheus Books.

- Feder, K. L. (2019). Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology (10th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Halmhofer, S. (2021). Did Aliens Build the Pyramids? And Other Racist Theories. Retrieved from https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/pseudoarchaeology-racism/

- Kershaw, S. P. (2018). The Search for Atlantis: A History of Plato’s Ideal State. New York: Pegasus Books.

Note: This chapter was adapted from a beta version of Traces.

David S. Anderson received his Ph.D. in Anthropology from Tulane University with a concentration on the archaeology of the ancient Maya. His fieldwork has focused on studying the development of Maya sociopolitical complexity and cultural institutions during the Preclassic period. This work has involved investigating the origins and growth of political power in a pre-state environment, as well as a critical examination of the role played by the Maya ballgame in development of community identity. When public interest grew around the Maya calendar in 2012, Anderson became increasingly involved in speaking out against false claims in archaeology. Today, his work examines the public perception of archaeology outside of academia by studying how the ancient world is depicted in pop culture and how popular audiences conceive of archaeology and archaeologists.

Part of this chapter is from Traces by Whatcom Community College and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Vocabulary

Context: The location in which an archaeological artifact is found.

Diffusionism: An archaeological theory that sought to explain change in the archaeological record by ideas or technologies diffusing, or spreading, from a single point of origin.

Empirical: Data that can be counted, measured, and quantified.

Epistemology: A branch of philosophy dedicated to the study of knowledge, colloquially phrased as “how you know what you know.”

Pseudoarchaeology: Claims that misrepresent the nature of the archaeological record and archaeological methods in order to support predetermined conclusions.

References

Blavatsky, H. (1888). The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy. New York: The Theosophical Publishing Company.

Colavito, J. (2005). The Cult of Alien Gods: H. P. Lovecraft and Extraterrestrial Pop Culture. Amherst: Prometheus Books.

Donnelly, I. (1882). Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Feder, K. L. (2019). Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology (10th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gomes, M. (2016). H.P. Blavatsky and Theosophy. In G. A. Magee (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Western Mysticism and Esotericism (pp. 248-259). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Halmhofer, S. (2021). Did Aliens Build the Pyramids? And Other Racist Theories. Retrieved from https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/pseudoarchaeology-racism/

Ingstad, H., & Ingstad, A. S. (2001). The Viking Discovery of America: The Excavation of a Norse Settlement in L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland. New York: Checkmark Books.

Kershaw, S. P. (2018). The Search for Atlantis: A History of Plato’s Ideal State. New York: Pegasus Books.

Kolata, A. L. (2013). Ancient Inca. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meltzer, D. J. (2021). First Peoples in a New World: Populating Ice Age America (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Pauwels, L., & Bergier, J. (1960). The Morning of the Magicians: Secret Societies, Conspiracies, and Vanished Civilizations. Rochester: Destiny Books.

Poole, W. S. (2016). In the Mountains of Madness: The Life and Extraordianary Afterlife of H.P. Lovecraft. Berkley: Soft Skull Press.

Protzen, J.-P. (1993). Inca Architecture and Construction at Ollantaytambo. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schele, L., & Miller, M. E. (1986). The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. New York: George Braziller, Inc.

University, C. (2018). Paranormal America 2018: Chapman University Survey of American Fears. Retrieved from https://blogs.chapman.edu/wilkinson/2018/10/16/paranormal-america-2018/

von Däniken, E. (1968). Chariots of the Gods? New York: Bantam Books.

Williams, H. (2012). The Kensinton Runestone: Fact and Fiction. The Swedish-American Historical Quarterly, LXIII(1), 3-22.

Claims that misrepresent the nature of the archaeological record and archaeological methods in order to support predetermined conclusions.

A branch of philosophy dedicated to the study of knowledge, colloquially phrased as “how you know what you know.”

Data that can be counted, measured, and quantified.

The specific location in which an artifact is found, and by association its relationship to other artifacts and ecofacts recovered from the same specific location.

An archaeological theory that sought to explain change in the archaeological record by ideas or technologies diffusing, or spreading, from a single point of origin