The Archaeological Process

B. Jacob Skousen

Learning Objectives

-

-

Describe the process of archaeological projects from start to finish.

-

Describe how archaeologists plan, conduct, and complete archaeological projects by following the archaeological process

-

Correct inaccurate and often romanticized views of archaeology by showing that archaeology is a process that does not just focus on fieldwork in exotic places

-

The purpose of this chapter is to describe the archaeological process, defined here as a generalized series of steps or tasks an archaeologist takes to successfully develop, conduct, and complete archaeological projects. The term “archaeological process,” however, is somewhat of a misnomer. The archaeological process is not a one-size-fits-all set of rules that one can simply apply to any archaeological project. Every project is unique and has its own goals, requirements, and challenges, which means that not every aspect of the archaeological process discussed below is required for all projects (though, as it will hopefully become evident, some steps are more important than others and are always part of any project).

Another critical point is that the archaeological process is fluid – an archaeological project, and the steps it requires, may not proceed in a simple, linear fashion. In many cases, the steps of the archaeological process and the order in which they occur depend on the context from which the project arose, as well as time, money, ethical concerns, laws and permits, other people, institutional and financial delays, and more. (See Special Topics Box 1 for a real-life example). Additionally, sometimes certain steps of the archaeological process bleed into or become intertwined with others. Still, this chapter will help those who want to better understand how archaeological projects transpire and the potential steps that archaeologists take to properly and ethically perform such projects.

Special Topics: Real-World Archaeological Project

Photo courtesy of Robert McCullough.

In March 2019, I was contacted by a man who owned a 100 acre tract of land in southeastern Illinois. He was interested in archaeology and, based on years of exploring, knew of several archaeological sites on his property. He had seen an online recording of a public lecture I had given about a separate archaeological research project I had conducted in the area, and asked if I would come and look at some of the sites on his property and the artifacts he collected from them over the years. I agreed, and we arranged a time to meet.

Upon meeting, he showed me some of the artifacts he had collected, and took me around the farm to the areas where he had found the artifacts. During the tour, he showed me red-colored soil that was eroding out of a stream bank (Figure 1x). I took a closer look, and it was clear that this red-colored soil was part of a buried archaeological feature, likely a hearth or fire pit, and that it would be destroyed very soon given the torrential rainstorms that frequent the area. I asked if he would allow me and a few of my colleagues to come back at another time and excavate this feature before it was destroyed. He agreed, and was excited to see what the excavation uncovered.

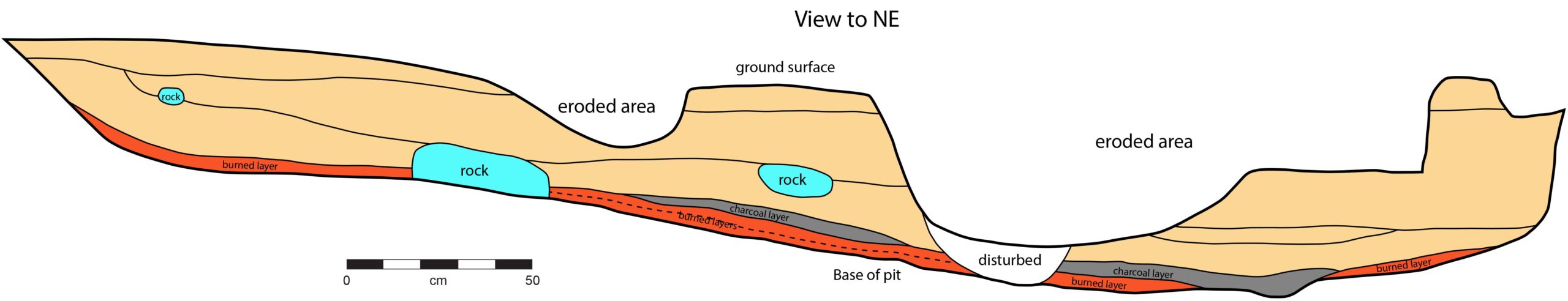

Several colleagues and I returned a few weeks later (April 2019) and, with the landowner, spent the day excavating the feature. The feature turned out to be a thin, oval-shaped, 12 foot long roasting pit, complete with rock lining and a layer of ash at the base of the pit that likely dates to sometime during the Archaic period, or roughly 8000-1200 BCE (Figure 2x). It was a long, exhausting day – my colleagues and I got up early; made the three hour drive to the site; uncovered, mapped, excavated, and photographed the feature in about six hours; recorded the control points with a high-accuracy GPS; backfilled the excavation hole by hand; and made the return trip all in the same day.

Figure 2x. Profile of precontact roasting pit in southeastern Illinois. Map courtesy of the author.

The landowner was excited about the find and the possibility that there could be others like it on his property. Together we decided to conduct a magnetometry survey on some of the sites on his property to get an idea of the number and density of subsurface archaeological features that may still exist. In December 2019, I applied for a small grant from a local historical society to pay for the survey. Unfortunately, I did not get the grant. Much to my surprise, in early 2020 the landowner made a generous donation to my employer, with the understanding that I would conduct a pedestrian survey on his property to record any remaining archaeological sites and conduct the magnetometry survey on some of these sites.

After nailing down work schedules and working around the harvest season and Covid-19 restrictions and concerns, we met at his property in October 2020 to conduct the pedestrian survey. The landowner, his brother, one of my colleagues, and I performed the survey, which confirmed the location of the sites already identified by the landowner. Based on the artifacts collected, some sites date from the Archaic period (~8000-1200 BCE), some date to the Late Woodland period (~600-1100 CE), and some date to the Mississippian period (~1100-1500 CE).

The magnetometry survey took place in November 2020. The setup was more complex. We first set up a series of 20×20 meter grids by hand over the sites we wanted to survey, after which I performed the survey, with help from the landowner and my 15 year old son (the latter of whom I had to bribe with a fancy dinner in exchange for his help). The results of the survey were excellent – clusters of intact subsurface features were evident on several of the sites. Unfortunately, the magnetometer survey was not completed during this trip, but we returned a year and a half later (March 2022) and completed the survey.

This project shows that the archaeological process often does not always follow a prescribed series of steps as described in this chapter – archaeologists often have to work with what they have, given time, money, and other logistical constraints. Still, as this example shows, projects can be successful even with constraints. In this case, it has provided important information about the history of the little-known region in Illinois. Additionally, it has and will continue to make a favorable impression on the landowner and his family and teach them a little about archaeology and its importance.

How Do Archaeological Projects Begin?

The vast majority of archaeological work that takes place in the United States (as well as in many other countries) are a result of either 1) research projects (often conducted by archaeologists who work at universities or research institutions) or, more commonly, 2) Cultural Resource Management (CRM) projects (https://textbooks.whatcom.edu/tracesarchaeology/chapter/__crm__/). Archaeological research projects, like research projects in other scientific disciplines, begin with a question or problem. The question or problem usually depends on the researcher’s interests and expertise. Some questions and problems are simple – for example, the questions “what people or cultures lived in this area and when?” are commonly asked when minimal archaeological work has taken place in a particular area or region. Such questions must be answered before archaeologists can formulate other questions. In contrast, some research questions are more complex. A researcher may want to know, for instance, when a group of people became sedentary or how people at a particular settlement constructed a collective identity.

Beginning in the second half of the twentieth century, an increasing number of archaeological projects were conducted under the umbrella of CRM archaeology. This was because of the increased need for infrastructure all over the world and, as a result of this need, a formal effort to establish cultural resource laws to protect important places, landscapes, buildings, artifacts, and so on from destruction during these infrastructure projects (Figure 1). Today, the majority of archaeological work performed throughout the world takes place as CRM projects (for information on the major cultural resource laws, see https://textbooks.whatcom.edu/tracesarchaeology/chapter/_crm_/ ).

Countries have their own versions of cultural resource laws, and each provides varying levels of protection for the archaeological record. In most cases, archaeologists hear or are informed of infrastructure projects – e.g., roads, powerlines, pipelines, power plants, housing developments, reservoirs – and are hired to perform archaeological work to comply with the applicable cultural resource laws. For example, the best-known federal cultural resource law in the United States, the National Historic Protection Act, requires that any development or improvement project that occurs on federal land or is funded by federal money must evaluate the potential impacts of these projects on cultural resources (archaeological sites, landscapes, buildings, artifacts, and so on). Based on the details of the planned infrastructure project, CRM archaeologists develop a plan to identify, evaluate, protect, excavate, and so on the sites and/or resources, complete with an estimate of how much money it will require to perform these tasks. Because they do not choose what kind of site or time period they investigate, CRM archaeologists investigate all sites, artifacts, buildings, monuments, landscapes, and so on within the project area and parameters and should always strive to make thoughtful, accurate recommendations to the developers on how to best conserve, record, or mitigate archaeological remains.

Some projects are more accurately called salvage archaeology. This is when archaeologists conduct archaeological work at a site that was partially destroyed or damaged, or is about to be destroyed or damaged, due to development, erosion or other natural processes, natural disasters, extreme weather events, civic and economic unrest, war, neglect, or looting (Figure 2).

These projects are often necessary because, unfortunately, not all CRM laws are created equal – some only protect certain kinds of archaeological and historical sites, or sites on certain types of land; additionally, laws are often not enforced due to limited time and resources. Even if CRM laws are enforced, the penalties for breaking these laws are not always severe enough to impel developers to comply with them. In the United States, for instance, CRM laws in some states do not protect archaeological sites on private property; thus, landowners can legally destroy sites with no archaeological evaluation or excavation. Fortunately, most states have laws that protect human remains and sites with human remains, regardless of who owns the land.

Salvage archaeology projects are challenging. More often than not, archaeologists hear about a site that is in danger and throw together whatever limited money, volunteers, and other resources to excavate, collect, and record any information they can before the site is destroyed. Thus, salvage jobs often have limited funding and labor, take place in poor weather conditions, and do not always employ ideal archaeological recovery and recording techniques (Figure 3). While such conditions are far from ideal, most archaeologists recognize that any work, even if incomplete and/or lacking ideal recovery and recording techniques, is better than nothing.

Perhaps the most crucial yet often overlooked aspect of beginning an archaeological project is to discuss ideas and possibilities with communities, individuals, and representatives with interest in or ties to the sites, objects, and time periods in question. These communities and representatives range from Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (or other Tribal representatives), to historical societies or organizations, to entire communities or groups with ties to an archaeological site. Ideally, archaeologists should develop research questions and projects in collaboration with these communities and individuals so that the interests and concerns of these communities and individuals are represented. Even CRM archaeologists, who generally do not choose where a project occurs or what sites are investigated, should actively reach out to interested parties, especially descendant communities, to inform them of the project

and to get their perspective on what sites, objects, and landscapes are important to them and why (link to indigenous archaeology chapter). In fact, these discussions and collaborations should continue throughout all steps of the archaeological process, regardless of the order, as best as possible.

Archaeologists consider the following eight steps when developing and performing a project:

-

-

-

- Background Research

- Research Design

- Obtain Funding

- Obtain Permission

- Conduct Fieldwork

- Process, Analyze, and Interpret the Data

- Curation

- Dissemination.

-

-

Background Research

In “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade,” one of the most iconic archaeology movies of all time, Indiana Jones, when describing the purpose and process of archaeology to a group of college students, stated that “70% of all archaeology is done in the library…research, reading.” This is one of the rare moments when Indiana Jones was correct. While the exact amount of time background research takes varies from project to project (meaning, it can be more or less than 70% of a project), it is nonetheless a crucial and time-consuming part of both CRM and research archaeology projects.

After receiving a particular project or developing a research question, the next step for an archaeologist is to conduct background research. Many CRM archaeologists call this a literature review. At the very least, this step involves reading about the project area – the local geology, plant and animal life, and environment; previously identified archaeological sites in the area; past excavations in the area; past property owners; and any man-made modifications to the landscape that might affect the integrity of an archaeological site or deposits. This information can be obtained from a variety of sources, including previous archaeological reports and publications, geological and environmental studies, recent and old maps of the area, local histories, newspapers, property leases, and census data. Often, it is useful to talk to landowners, collectors, or individuals living in the area who know the history, local archaeology sites, and activities that took place in the area. This information can help archaeologists contextualize and interpret what they find.

As stated earlier, research projects are developed by asking research questions. Regardless, an archaeologist conducting such projects should research the same things as a CRM archaeologist – the environment, site history, modifications to the landscape or site in question, and other archaeological sites and projects in the area. In addition, an archaeologist should read about past research on the topic in question. If a researcher wants to conduct a project on farming practices during the Classic Maya period in the Maya Lowlands, they should be familiar with publications that describe the local rainfall and soils, the kinds of crops that were grown, methods of farming used in the past, the tools used for farming, theories about plant domestication in the region, and the development and history of agriculture in the Maya Lowlands. No doubt there would be other related topics and information a researcher would want to know when developing this kind of project. This information provides context and helps generate more informed, worthwhile questions.

Develop Methods or a “Research Design”

Archaeological methods refer to the procedures, techniques, and instruments one uses to complete an archaeological project. There are all kinds of methods that are commonly used by all archaeologists; some of the most basic field methods, for instance, include pedestrian survey, shovel testing, and hand unit excavations. However, the specific ways these methods are performed vary widely. As just mentioned, remote sensing is a basic method regularly employed by archaeologists, but there are many different kinds of remote sensing techniques, and the methods used for these are different – each requires different bodies of knowledge, instruments and tools, walking in certain ways and at certain speeds, software packages to process the data, and more. A formal statement of the project goals and the methods that will be used to reach the project goals is called a research design. Many of the field methods typically used in archaeological projects – surveys, GIS, remote sensing, excavation, and so on – will be described in the next two chapters in this textbook.

For research projects, developing the research design depends on the questions being asked. A researcher who is interested in determining the distribution and chronology of ancient settlements in a particular region, for example, should use methods to identify archaeological sites over a wide area and determine the chronology of these sites. The methods would almost certainly include pedestrian survey and perhaps shovel testing and remote sensing techniques to identify the number of sites within the area in question. Additionally, it would include collecting diagnostic artifacts from sites to determine when in time the site was used or inhabited. A researcher interested in changes in diet would perform excavations on certain portions of sites where cooking, food preparation, and other forms of food consumption occurred.

For CRM projects, the methods depend on the scope of the job. Overall, basic archaeological methods and techniques are the same regardless of whether it is a CRM or research project – pedestrian survey is still pedestrian survey, though exactly how one is performed can vary slightly. Phase I projects generally require literature reviews and pedestrian surveys, shovel testing, or geophysical surveys to determine whether archaeological sites exist, the size of existing sites, and the integrity of the sites. Phase II projects often require more intensive testing such as test unit excavations. Phase III projects are more extensive, sometimes involving the complete excavation of a particular area or site. In addition to fieldwork, CRM projects usually require at least basic analyses of the materials recovered in order to evaluate the type of sites that exist, their chronology, and their historical importance; the methods in which each material type is examined depend on the project goals and research questions.

Of course, the methods chosen also depend on the amount of money and time available for the project. This is why obtaining money for both CRM and research projects is a crucial step in the archaeological process (see below). Those who have the necessary funds generally have no problem following the methods outlined in the research design in order to complete the project. Time also plays a significant role in the type of methods one uses; for example, archaeologists often have limited time when performing salvage excavations, and this changes the methods employed during the salvage work.

If the project requires fieldwork, it is important that the methods developed are the least destructive option but will still answer the research question or fulfill the project goals. For example, if a research question can be answered by examining collections from museums or curation repositories that were obtained during past archaeological projects, then that is better than performing additional fieldwork to gather more data. If excavating ten 1×1 meter test units in carefully chosen locations of a particular site will provide enough information to answer the research question, then there is no need to conduct more extensive excavations. Remember, the archaeological record is finite and excavations are destructive and expensive, so archaeologists should make every effort to minimize the impact their research will have on the site. On the other hand, complete excavation of a site may be necessary if the site will be destroyed.

Collaboration with descendent communities is crucial when developing methods for a project. Some places, landscapes, monuments, buildings, and so on are important, and in some cases sacred, to particular communities, and these communities may not want these places or things to be excavated or altered, and would prefer that non-invasive techniques (e.g., remote sensing) be used instead. Thus, it is vital that an archaeologist develop research projects, and particularly the methods used in these projects, in collaboration with descendent communities.

Obtain Funding

Funding is a critical, if not necessary, step in the archaeological process. CRM projects always involve funding of some kind. Traditionally, upon getting word of a potential archaeological project, a CRM company submits an estimate of how much money the project will cost to complete. After reviewing the estimates submitted by interested CRM companies, the employer hires the desired CRM company to perform the project based on the CRM company’s qualifications, reputation, and, more often than not, the estimate provided. Unfortunately, since employers are more likely to hire the CRM company that submit low estimates, this often encourages CRM companies to submit the lowest possible estimate in order to get the job. This, in turn, can sometimes lead to shoddy or incomplete work.

Obtaining funding is different for research projects. In most cases, research projects are performed by archaeologists in academia (i.e., those who teach at colleges or universities), and they must obtain outside funds to conduct these projects, whether they be field-based, laboratory-based, or something else altogether. Funds can come from a variety of sources, but grants are the most common source. In the United States, some of the more popular federal funding sources are the National Science Foundation (www.beta.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/archaeology-and-archaeometry-0) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (www.neh.gov/grants), where funds come from taxpayer money. Conversely, funds can come from various anthropological or archaeological professional organizations, such as the Archaeological Institute of America (www.archaeological.org/programs/professionals/grants-awards/), the National Geographic Society (www.nationalgeographic.org/society/grants-and-investments/), or the Wenner-Gren Foundation (www.wennergren.org/programs). Since these are generally nonprofit organizations, their grant funds mostly come from fundraisers and private donations. Each of these organizations fund archaeological research all over the world and even non-archaeological research projects, which means that obtaining funding from these organizations is very competitive and often takes multiple submissions to obtain.

There are numerous other sources of funding for archaeological projects. Less often, funds come directly from private individuals who have an interest in particular archaeological topics or sites. In these rare cases, such individuals typically contact archaeologists who are actively performing research associated with the same topics or have an interest in the same archaeological sites. Additionally, academic institutions (colleges and universities) often provide “internal” grant funding for faculty research, which can include archaeological projects. Sometimes departments with archaeology faculty members provide funding for the archaeology faculty members to organize and run field schools, which is often part of a larger research project or agenda of the faculty member. Even small, local- or state-based archaeological groups or organizations provide funds for small-scale projects.

As one might expect, the amount of funding required for a project depends on the goals of the project and the size of the entity or organization providing the funds. Small projects, for the most part, require less money, which means that an archaeologist could apply for smaller, less competitive grants from a local or state institution or group. Conversely, large projects require more money, so applying for larger, more competitive grants makes more sense. The type of work being conducted for a project also dictates where one seeks funding – for instance, a project that involves large-scale excavations require more money (remember, excavation is time-consuming and expensive!), whereas a project that involves a large-scale pedestrian survey would require less money, since pedestrian survey is far less expensive. Specialized analyses are often more expensive because certain resources are required to conduct the analysis, and only a small number of people have the knowledge, skills, and facilities to perform such analyses. Thus, archaeologists must carefully consider and calculate the amount of money needed to perform the required work, regardless of whether the project involves field or lab work, particular tests (radiocarbon dates), different kinds of analyses (such as lithic or ceramic analysis as well as more specialized analyses such as residue analysis), curation of the material and data produced during the project (see below), and costs related to publication and dissemination (see below).

Obtain Permission

This step is necessary for any archaeological project, and generally occurs in tandem with obtain funding. In most places around the world, there are cultural resource laws that protect archaeological objects, collections, sites, monuments, and landscapes. Thus, archaeologists who wish to conduct research on a particular collection or at a particular site or area should know the applicable cultural resource laws and then obtain permission from the government officials or agencies who oversee and enforce these laws. In most cases, obtaining permission requires that an archaeologist apply for a permit. Applications usually include project descriptions, timelines, methods, researcher qualifications, and the intended products. Such applications are required for both CRM and research or academic archaeologists. In addition to protecting cultural resources, permits also ensure quality control in that permits are only granted to qualified and competent archaeologists. The time it takes to apply for and obtain permits varies – since obtaining permits can be a long, drawn-out process, archaeologists should plan accordingly to meet to project deadlines and goals.

If the proposed project is supposed to take place on private land, the archaeologist must also obtain permission of the landowner before conducting the work. Depending on the cultural resource laws in a particular area, an archaeologist may not always need to obtain a permit from a governmental organization to work on private land, but it is almost always necessary to obtain permission from the landowner. This is a less formal, more fluid, and sometimes more frustrating process. In some cases, landowners are very interested in archaeology and gladly allow archaeologists to perform work on their property. More often, however, landowners are hesitant of and sometimes openly hostile to anyone who requests access to their property, including archaeologists. Even if a landowner accepts that you are a professional archaeologist, they are still often suspicious. Reasons for suspicion vary. In my experience doing archaeology in the midwestern United States, landowner hesitancy results from numerous things. A common reason is a mistrust of “The Government,” which includes the laws and regulations governments enact and enforce (this issue is especially tricky for archaeologists who are employed by government entities). Some landowners do not trust “academics,” or archaeologists who teach at universities. Another common reason is that landowners generally are wary of “outsiders,” or anyone who is not part of the local community. Some landowners believe that archaeological remains and sites are worth a lot of money; thus, the landowner wants to keep any potential “treasures” for themselves. Finally, some landowners are concerned that the government will somehow co-opt their property because of an archaeological site or find. This concern can bring out the worst in people – the handful of times that I have been threatened by landowners after asking to perform archaeological work on their property is because of this belief. Archaeologists performing work in other countries encounter these and other concerns; in fact, some foreign archaeologists are often accused of being spies by local populations! While these concerns are unfounded and based on inaccurate views of cultural resource laws and the discipline of archaeology, the point is that archaeologists should never assume that landowners will be open to or supportive of an archaeological project on their property.

One of the best ways an archaeologist can limit and sometimes alleviate suspicion and hesitancy among local populations and landowners is to establish relationships with residents in the regions where they work (Figure 4).

Generally, people are more willing to have a conversation with and trust archaeologists who are friendly, relaxed, not demanding, understanding, and interested in the community’s well-being (and not just the archaeology within the community). More to the point, when communities and landowners know and have positive relationships with archaeologists, they are more willing to allow archaeologists to conduct work on their property, and in the best-case scenarios, landowners become interested in and participate in the project and work to preserve the site. Obviously, building relationships of trust with local communities takes time, effort, and patience; for those who work exclusively in certain areas or regions, building these relationships is and should be a career-long pursuit. Regardless of how one chooses how to build relationships of trust, it is important to factor in the time, effort, and money this requires into project timelines.

For lab-based projects, an archaeologist must obtain permission and permits to perform the work. If an archaeologist is interested in analyzing a collection from a museum, for instance, they must first secure permission from museum curators and staff to examine the collection, which often requires applying for a permit, much like archaeologists performing field projects. The permit process is more complicated if analyses are destructive – examples of such analyses include radiocarbon dates on botanical samples, some pottery residue analysis techniques, and DNA studies on animal or human bone (for ethical issues on bioarchaeology work see https://textbooks.whatcom.edu/tracesarchaeology/chapter/__bioarchaeology__/). Remember, any lab-based project, including the goals, methods, and what materials and collections can be handled, should be done in consultation with descendent communities. Even if this is not specifically required by law, collaboration is the ethical thing to do.

Conduct the Fieldwork

This is perhaps the most variable part of the archaeological process that often, though not always, takes the least amount of time compared to other steps in the archaeological process. Archaeologists often call this step data collection. The way a project is conducted should follow the research design that was developed earlier in the project and specified in permits and grant proposals (see above). This is also the step that receives the most press – we’ve all watched documentaries and read popular articles that showcase archaeologists unearthing the remains of King Richard III and later confirmed by DNA analysis (www.archaeology.org/news/500-130204-richard-iii-skeleton-identified), x-raying Egyptian animal mummies (www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/x-ray-ancient-animal-mummies-egypt), and discovering Maya monumental architecture in the jungles of Central America through remote sensing technology (www.sciencenews.org/article/lidar-reveals-oldest-biggest-ancient-maya-structurue-found-mexico).

While this step in the archaeological process captures public attention, it also feeds into the widespread but problematic and overly-romantic view that archaeology is all about uncovering “secrets” of past peoples, and that archaeologists are rugged explorers who spend most of their time excavating in the field, and sometimes dealing with dangerous situations. Of course, many archaeologists, myself included, love being in the field – it allows us to see landscapes and places we would not see otherwise, see interesting artifacts and features, and literally reconstruct history as it is being unearthed. And fieldwork can indeed be hazardous (cuts, bruises, sprained ankles, and heat-related maladies are very common, and I have had the misfortune of nearly being stampeded by an elk herd, struck by lightning, stung by scorpions, and arrested by a military police force in another country, all of which are fascinating stories for another time). The problem is that notions of discovery, danger, and adventure overshadow the goal of fieldwork, which is to recover information that can be used to reconstruct and interpret the past, as well as the methodical, often mundane techniques used in fieldwork, such as writing detailed descriptions of contexts, making maps, taking photographs, describing soils, and bagging artifacts (insert link to Excavation chapter here).

Additionally, field school courses can perpetuate the idea that fieldwork is the most important part of archaeology. Such courses are required for archaeology undergraduate students at many universities, viewed as the culmination of one’s archaeological training, are a primary requirement for getting one’s first archaeology job and becoming “a real archaeologist.” While such field-based courses are undoubtedly important and necessary, and beginning archaeologists should participate in these courses if possible, they are overemphasized compared to other parts of the archaeological process. In sum, with the heavy emphasis on fieldwork, there is little to no understanding among aspiring archaeologists that there is a process to archaeology, and that only a small portion of archaeological projects occurs in the field, and that archaeology also involves other forms of hard work that takes place in libraries, labs, and museums.

Processing, Analysis, and Interpretation

After the materials are collected during the “data collection” or fieldwork part of the project, these data need to be processed, analyzed, and interpreted. In most cases, this step takes the most amount of time out of all the steps of the archaeological process. A common rule of thumb is that for every month in the field or collecting data, it takes another three months of work to process and analyze the information recovered; of course, the exact amount of time for processing and analysis depends on the project, the type of data collected, and the types of analyses one performs (for more information about the types of analyses archaeologists often perform, see Ancient Technologies chapter).

At minimum, processing artifacts involves washing, sorting, and labeling each artifact with basic contextual information (such as the site, feature, and level from which the artifact was recovered) (Figure 5).

Artifacts are then rebagged in curation-standard containers or bags, which are also labeled with provenience information. The types of bags and the information required depend on cultural resource laws and/or the institution or facility curating the material, so it is crucial that archaeologists are familiar with applicable cultural resource laws and have a plan for curation as well as understand the requirements of storage facilities or museums (see below). While processing artifacts sometimes seem like a tedious task, it is often part of field schools or lab analysis classes, and is one of the first jobs with which a beginning archaeologist is tasked. This is because processing artifacts is an excellent opportunity to learn how to identify and handle different artifact types, which is vital for fieldwork, lab work, and basic inventories.

Artifacts are not the only type of information that archaeologists collect during a project. Notes, maps, and other forms and paperwork are a standard part of most field projects (Figure 6).

In such situations, an archaeologist must ensure that the physical documents, notes, maps, and so on are completed, checked, and rechecked for clarity and accuracy after data collection is completed. Then, these documents, notes, and maps should be scanned into a digital format. This is now common practice – digital data takes far less room and management than hard copies, and they serve as a backup in case the hard copies are lost or destroyed. If other types of data are collected, they too must be processed. Remote sensing data, for example, must be organized, cleaned up, and backed up; GIS data must be downloaded into appropriate GIS software programs and incorporated into both physical and digital maps; results of a residue analysis on pottery must be tabulated, backed up, and rendered into graphs or charts for necessary comparisons.

Next, the data need to be analyzed. Again, the analyses that take place depend on the goal of the project or the research questions being asked and, of course, the types of data that are collected (Figure 7).

As implied earlier, most CRM projects involve, at minimum, determining the chronology of a site or artifact. This usually requires a basic analysis of potentially diagnostic artifacts such as pottery or formal lithic tools; this is easier when certain artifact “types” and chronologies in a region or area have already been established by previous researchers. When no diagnostic artifacts are recovered, archaeologists often resort to absolute dating techniques, such as radiocarbon dating; since most archaeologists lack the equipment and expertise for performing such analyses, appropriate samples are sent to accredited labs that are equipped to perform those analyses. While some research projects only require basic analyses, others often involve more targeted questions that require different types of analyses. Again, the types of analyses should already have been specified in research designs, grant applications, and permits.

Curation

Curation is one of the most important but underappreciated and neglected steps in the archaeological process. Curation is the practice of cataloging, preserving, storing, and caring for archaeological collections and data. As mentioned earlier, every archaeological project, no matter the type, size, or scope, involves the production of some kind of data. These data can include physical remains (artifacts, samples, paperwork, maps) and/or digital data (digital photographs, scanned paperwork, digital forms and data tables, GIS data, 3D scans of artifacts, geophysical data). These data must be stored and preserved in appropriate curation facilities or museums to ensure that they are available to other archaeologists, researchers, and interested parties for future research, displays, education, and appreciation (Figure 8).

Permanent curation and care of data should be a part of every plan or research design for an archaeological project. This requires, first, that arrangements are made and money is secured for curation before a project even starts. To do this, the archaeologist generally contacts a curator or collections manager from an accredited facility or museum to see if the facility is able and has the room to curate the data that will be generated during the project. Of course, the amount of data collected during some projects is not always known; thus, an archaeologist must make a best estimate. Sometimes cultural resource laws stipulate the particular museum or facility where the data must be curated, which again means that archaeologists must be aware of the laws and regulations in the region where they work. After the archaeologist finds a curation facility that is able and willing to store the artifacts, the next step is to generate a written document that states the parameters of the agreement. Specifics of agreements vary, but they typically include the parties entering the agreement, the types of data/collections to be curated, dates of transfer of the data/collections, required curation costs, and standards for the data (e.g., artifacts washed and labeled, artifact bags labeled, digital data in a certain format). In many cases, these details and templates of such agreements have already been established by the institution.

Often curation facilities and museums do not accept so-called redundant artifacts – such as fire-cracked rock, rubble, and unmodified rocks – that provide “redundant” information, or archaeological data that is repetitive and thus does not add to the interpretation of an archaeological site or area (Figure 9).

The reason for this is because of the curation crisis, a term that refers to the ever-growing shortage of storage space available to properly curate and care for archaeological collections. In these cases, archaeologists must collaborate with curators to determine the facility’s policy, and what an archaeologist must do to cull the necessary artifacts in preparation for curation.

Dissemination

One of the final steps of the archaeological process is dissemination, or informing other researchers and the public of the results of archaeological projects through reports, articles, presentations, and outreach. In many ways, dissemination of archaeological information and knowledge is the culmination of an archaeological project. Furthermore, this is one of the most crucial steps in the archaeological process because of the oft-quoted notion that nobody “owns” the past. The upshot is that archaeologists are ethically obligated to share knowledge and project results with as wide an audience as possible.

One of the most common ways that archaeologists do this is through publication. There are a wide variety of publication venues. Perhaps the most common publication venue for CRM archaeologists are reports. In many cases, reports are required by the laws that drive CRM archaeology – these reports contain the results of the project, the importance of the work to the sites and artifacts found to the field of archaeology and history, and recommendations or suggestions regarding how to proceed with a given infrastructure project. Research archaeologists, on the other hand, typically publish the results of their work in peer-reviewed journals and books. While these kinds of publications usually present some form of data, they often also address larger research, theoretical, and methodological questions. Additionally, both CRM and research archaeologists present their findings at professional archaeological meetings and conferences, and sometimes even in introductory-level textbooks like this one.

While publication is crucial and often considered the pinnacle of dissemination, it should not end there. Indeed, these formats of dissemination only reach certain audiences. Reports, for example, are generally only read by CRM archaeologists and their employers, and often become gray literature, which means they are not widely known and difficult to acquire. Research articles are typically read by academics and researchers associated with research institutions or universities; it can be hard for the general public to obtain access to such sources. Fortunately, this problem is slowly getting better as archaeologists are beginning to publish their work in “open source” journals and formats, which are available to the wider public.

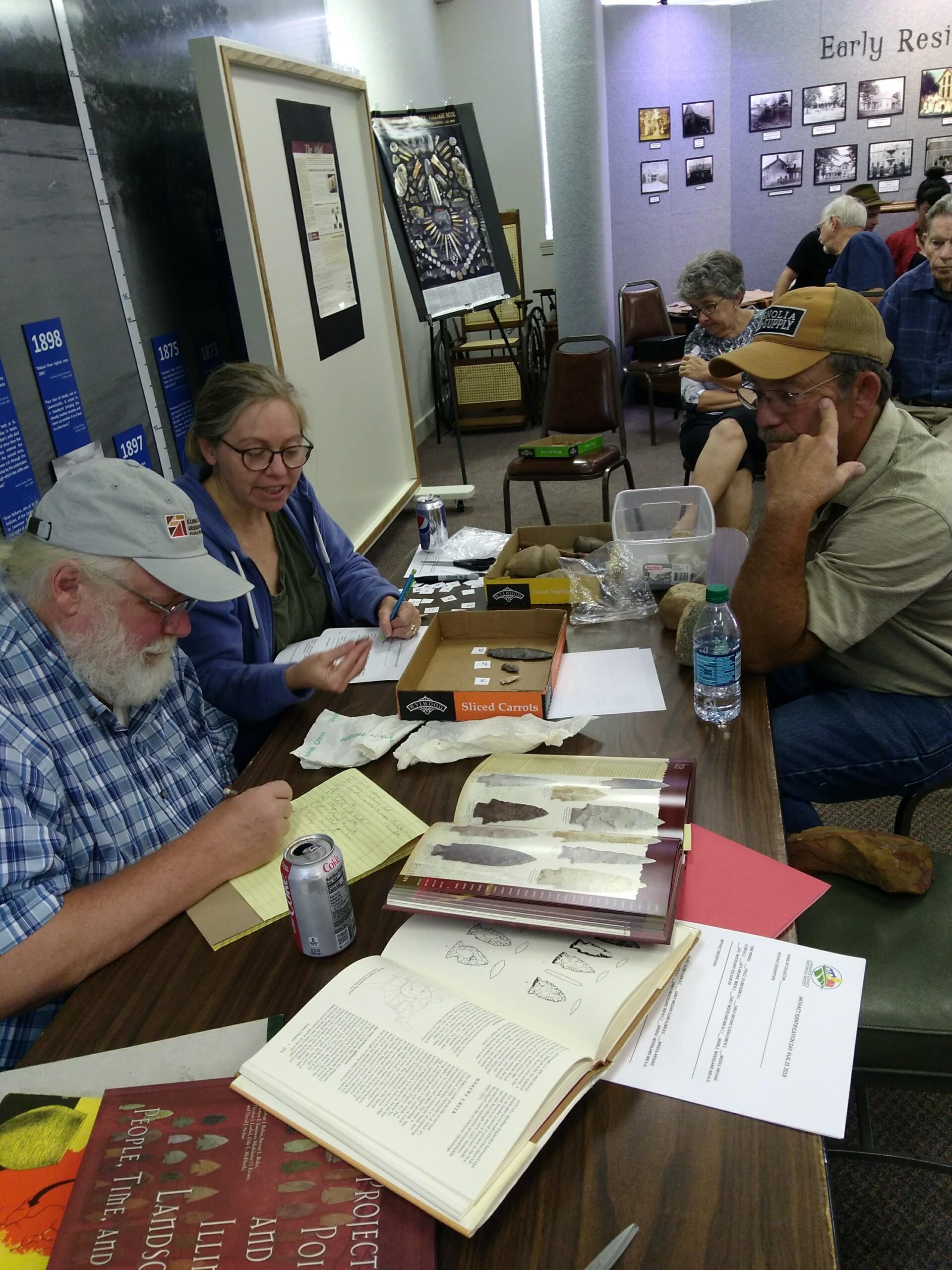

In order to reach broader audiences, archaeologists often present their findings at public outreach events (https://textbooks.whatcom.edu/tracesarchaeology/chapter/_publicoutreach_/). This can include giving public lectures or talks at local libraries and historical societies, giving presentations to primary school children, making booths and posters for local gatherings and events, organizing public artifact identification events, or leading tours of archaeological sites (Figure 10).

Some archaeologists attempt to share their research through designing displays in museums and local historical societies. More tech-savvy archaeologists create blogs, videos, and social media posts on archaeological projects, which tend to be shared far more widely than other formats. Finally, some archaeologists are interviewed by local radio stations, newspapers, and TV networks about a project. This is a rare opportunity to share information with a wider audience who would otherwise not be exposed to archaeology. Of course, there is always a risk that reporters will not accurately convey or summarize the information provided by an archaeologist, so in these situations archaeologists must take extra care to be clear and concise in their statements, and if possible, proofread the interview or statements to ensure they are accurate.

While sharing archaeological knowledge with the public is vital, it is important to understand that archaeologists also have a responsibility to not share sensitive information about archaeological sites that would make it possible for members of the public to loot, damage, or conduct their own “investigations” at archaeological sites. For instance, when presenting to public audiences, archaeologists should not disclose site locations; they should also be sure to strip out any location information attached to or embedded within digital photos when posting them on social media platforms. In the past, I have had to specifically ask reporters not to share the exact location of archaeological sites, both for the sake of the landowner’s privacy as well as to ensure the safety and preservation of the site. While most people who hear such reports would not deliberately loot or perform illegal activities at a site, it is better to play it safe.

Conclusion

The primary goals of this chapter were to provide an overview of the archaeological process; help readers understand how archaeologists plan, conduct, and complete archaeological projects by following this process; and correct inaccurate and often romanticized views of archaeology by showing that archaeology is a process that is not just about performing fieldwork in exotic places. Knowledge of this process helps archaeologists plan ahead and react to the often fluid and unpredictable nature of archaeological projects; it is also necessary for anyone who is interested in becoming a professional archaeologist. Moreover, while not all projects require every step of this process, and the order in which these steps proceed vary, it is hopefully clear that some steps, such as curation and dissemination, are always part of any archaeological project. Perhaps the most important point is that each of these steps should be conducted in collaboration with communities, groups, and individuals who have historic ties to the sites and landscapes in question.

Discussion Questions

- When should engagement and collaboration with descendant communities occur during the archaeological process? Why?

- What is the most important step in the archaeological process? Why?

- Which steps in the archaeological process are best known among the general public? How can a focus on these few steps lead to romanticized views of the field of archaeology among members of the public?

- How might an understanding of the archaeological process help overturn incorrect, problematic, or pseudoarchaeological perspectives? Why?

Note: This chapter was adapted from a beta version written by the author.

B. Jacob Skousen is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Western Illinois University. He has been a professional archaeologist for nearly 15 years, and while most of this experience has been in the North American Midwest, he has archaeological experience in the North American Great Basin and Southwest, Central America, and the Middle East. His research focuses on the Mississippian period, the precontact city of Cahokia, pilgrimage, and identity formation. In the rare moments when not doing archaeology, Jacob enjoys being outside, taking walks, exercising, gardening, and playing the piano.

This chapter is from Traces by Whatcom Community College and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

a generalized series of steps or tasks an archaeologist takes to successfully develop, conduct, and complete archaeological projects.

An ad hoc process of extracting whatever one can from an archaeological site in imminent danger of destruction from natural catastrophes (e.g., forest fires, shoreline erosion) or construction occurring outside of the archaeological review process.

when an archaeologist conducts background research before starting a project. This can involve studying the local geology, plant and animal life, and environment; previously identified archaeologists sites and projects in the area; past property owners, man-made modifications to the landscape; and other research that has been conducted on the time periods, cultures, and research topics the archaeologist is interested in.

the procedures, techniques, and instruments one uses to complete an archaeological project.

A formal statement of the project goals and the methods that will be used to reach the project goal or goals.

a part of the archaeological process when archaeologists gather data, either through remote sensing, survey, excavation, analysis, etc.

the practice of cataloging, preserving, storing, and caring for archaeological collections and data.

refers to the ever-growing shortage of storage space available to properly curate and care for archaeological collections.

informing other researchers and the public of the results of archaeological projects through reports, articles, presentations, and outreach.

reports and other documents and forms of dissemination that are not widely known or distributed and difficult to acquire.