8 Limits to Human Growth on Earth?

Chapter Outline:

Are human societies able to continue growing forever, or are there limits to the Earth’s carrying capacity?

- Population Growth & Resource Scarcity

- Climate Activism

Population Growth & Resource Scarcity

One of the most basic but often overlooked aspects of human interactions with the environment that has come to the attention of historians and more recently the public is the impact of population growth and resource scarcity. There are a number of reasons society prefers to avoid thinking about the danger of having too many humans around. We like people. Especially those who are close to us. And historically, the growth of our own particular group has been important for our survival and therefore has been desirable. In the past, people haven’t always been too concerned if the success of their particular community came at the expense of their neighbors. But recently that neighborhood has expanded to cover the whole globe.

At the very beginning of the modern age, an English economist named Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834) published a short book called An Essay on the Principle of Population. Malthus’s theory, published in 1798, became instantly controversial on both sides of the Atlantic. Thomas Jefferson sent a copy of the book to his favorite economist (Jean-Baptiste Say) and asked for an opinion.

Malthus stated his basic idea like this:

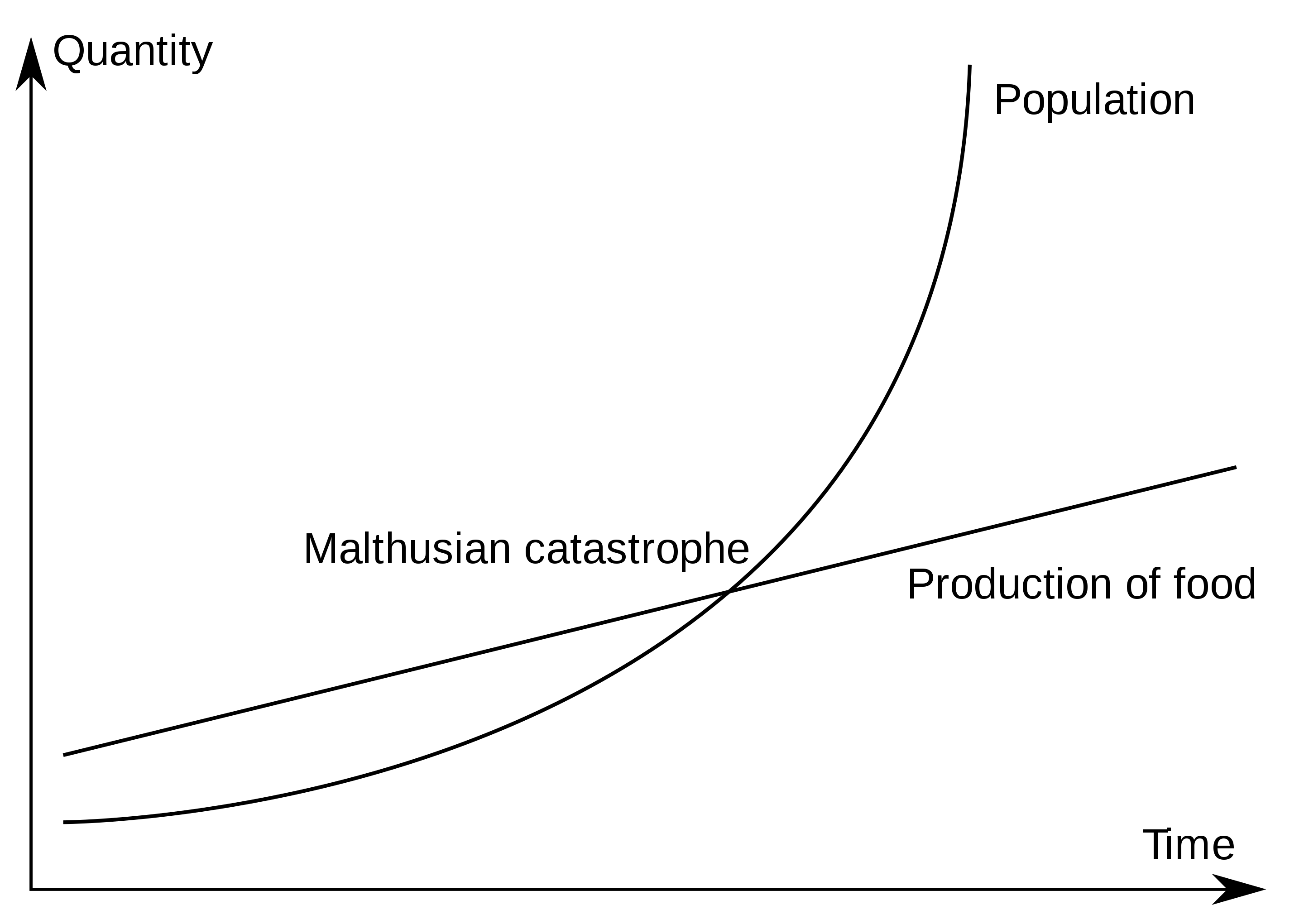

Malthus went on to observe that populations tend to increase geometrically: two people become four, four become eight, eight become sixteen, etc. In contrast, he said, food supplies at best increase only arithmetically: two bushels of wheat become four, which become six, which become eight. By this logic it is easy to see that a society can easily outrun its ability to feed itself if the population is not kept down by reducing births or increasing deaths, and to understand why early modern Europeans were so obsessed with acquiring new territories to improve their food production abilities.

It turns out, however, that the assumption held by Malthus and those members of the British upper class (and by many people today) that feeding the poor would lead to a population explosion is actually untrue. Population scientists today agree, after studying societies all over the world, that as economic security increases, a “demographic shift” occurs and birth rates decline. In other words:

-

- if the poor have enough to eat, infant mortality rates and people’s fear of starving in their old age decrease.

- death rates of children decline and as a result parents needing to insure that someone will survive to take care of them in their old age have fewer children.

- educating women is the other major factor demographers have credited with reducing birthrates.

In spite of the developed world’s success limiting population growth by providing education for women and a social safety net, the argument is still raging regarding the “developing world.” The Gates Foundation recently started a campaign called #StopTheMyth. A few years ago Melinda Gates made a short video titled “You Decide: Save the People or Save the Planet,” claiming that the issue is still very poorly understood.

Until very recently in human history, the Earth has been so big and the total human population relatively so small, that the resources available to us have often seemed infinite. In 1800 there were fewer than a billion people on the planet. In 1900 there were still less than two billion. By 1960 there were three billion, and in 1999 there were six billion. Current world population is about 7.7 billion people. During this dramatic increase, there were periods like the early industrial revolution when worriers like Malthus and his followers expressed doubts and anxiety.

Malthus had no idea that his nation was about to expand its empire into Africa and Asia, or that emigration to the Americas and Australia would continue to reduce populations at home. And of course he couldn’t anticipate advances in technology or the demographic effects of increasing economic security we have just considered. But sometimes even these advances proved temporary or subject to disruption.

The population of Ireland boomed in the first decades of the nineteenth century, as potatoes increased the calories available to poor people and seemed to eliminate the threat of famine. The Irish population peaked at over 8 million in 1841, based on the potato. About a third of all Irish people ate no other solid food, and lived on a diet of milk and potatoes. Worse, the entire nation (indeed all of Europe) grew just a single variety of potato, called the Irish Lumper. The blight that attacked this monoculture and destroyed potato harvests for several years in Ireland and throughout Europe killed over a million people and forced a million more to flee to America. The Irish population is about 4.8 million today, a little more than half its peak 175 years ago. As the science of ecology developed in the second half of the twentieth century and we began to distinguish between renewable and nonrenewable resources, and to worry about the dangers of depending on monoculture food supplies. Malthusian anxiety has returned.

In 1968 Stanford University Biology professor Paul R. Ehrlich published a sensational book called The Population Bomb, that was an instant bestseller. It began with the statement, “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date, nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.” Ehrlich became an instant celebrity and publicized his theories of social collapse on popular media like Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. The Population Bomb, however, may have done more harm than good in the long run, by making worry over the population issue an easy target for critics. Yet, people remained concerned about the rapid increase of the world’s human population.

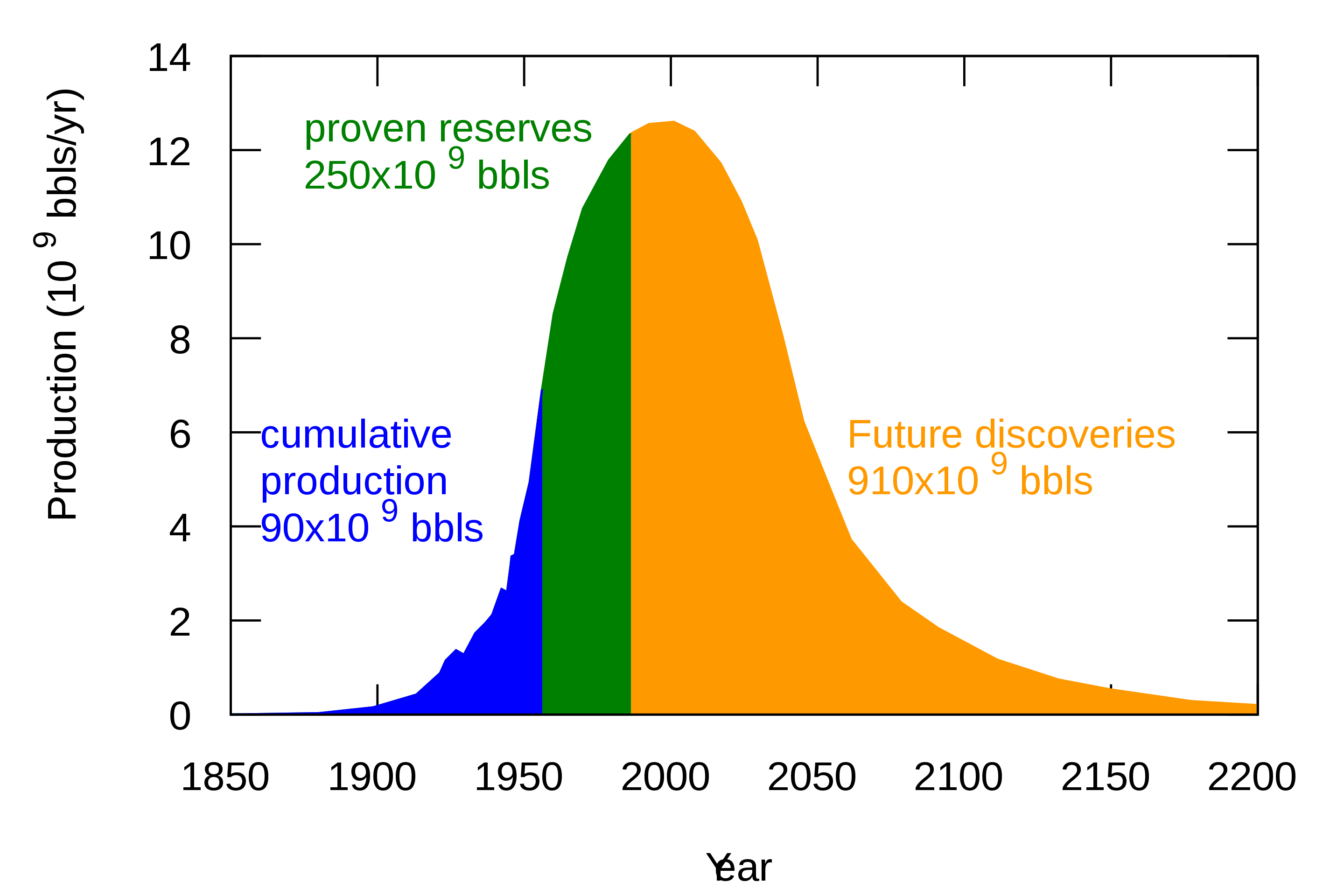

Not all the warnings that humanity is reaching resource limits have come from university academics or international think-tanks that are naturally distrusted by regular people and corporate leaders. Marion King Hubbert was an American geophysicist working for Shell Oil in 1956 when he presented a research paper to an oil industry trade group, The American Petroleum Institute, where he showed that for any geographical area (and by implication, for the planet as a whole), petroleum production follows a predictable bell-shaped curve. Hubbert’s theory, which became known as Peak Oil, correctly predicted that oil production in the continental US would peak between 1965 and 1970, and then begin to decline. Hubbert also predicted that world oil production would peak “in about fifty years.” Although the data and especially its interpretation are very controversial, several credible sources suggest that the peak in world production happened between 2003 and 2004, right on Hubbert’s schedule. Hubbert’s words actually echoed Malthus.

Some have argued that possible future discoveries of more oil could postpone society’s shift to a non-fossil fuel energy economy. So the question we are left with is, how quickly will we use up what remains? And, given what we have learned in the last decade about the effect of burning fossil fuels on the global climate, should we?

The United States Geologic Survey (USGS) conducted a 2000 study of the remaining and potential energy reserves across the planet and it holds some idea of when we will run out of traditional, “fossil-fuel” forms of energy. The assessment process utilized geologic analysis and probability methodology for a remaining potential estimate of 159 TPS and 274 AU. Recoverable oil—production, reserves, reserve growth, and undiscovered reserves was estimated at 3 trillion barrels of oil (TBO). The natural gas is estimated at 2.6 trillion barrels of oil equivalent (TBOE). Oil reserves were 1.1 TBO; world consumption in 2000 was .028 TBO per year. Natural gas reserves were 0.8 TBOE; world consumption is about 0.014 TBOE per year. So oil, gas or natural gas liquids add up to 2 TBOE of proven petroleum reserves. Given a global oil and gas estimate of about 5.6 TBOE, the USGS estimated the world by 2000 had consumed 1 TBOE, or 18%, leaving about 82% to be utilized or found. Fifty percent of the world’s undiscovered potential is undersea. Arctic basins hold 25% of undiscovered petroleum resources and that is where Russia is operating now.

Climate energy modeling groups such as those at Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology estimate potential oil shortfalls in 2020-2040 dependent on the exclusion or inclusion of OPEC (Organization of Petroleum-Exporting Countries) in the estimate. Thus a transition to natural gas; with its methane environmental issues, is a short-term possibility. However, natural gas may experience supply problems by 2050-2060 depending on the rate of conversion from oil to natural gas and the annual global usage rate of natural gas. Coal resources are considerable and provide significant petroleum potential either by extracting natural gas from coal, or by coal conversion to petrol products, or by utilizing coal-generated electricity. All have pollution risks to the environment that are substantial. Finally, there are alternative forms of oil, natural gas, and more in non-traditional forms that could be tapped but the costs, both environmental and financial are yet to be fully measured.

Thomas S. Ahlbrandt. “Future petroleum energy resources of the world.” International Geology Review, 2002, v.44(12), pp. 1092-1104. Taylor & Francis.

Climate Activism

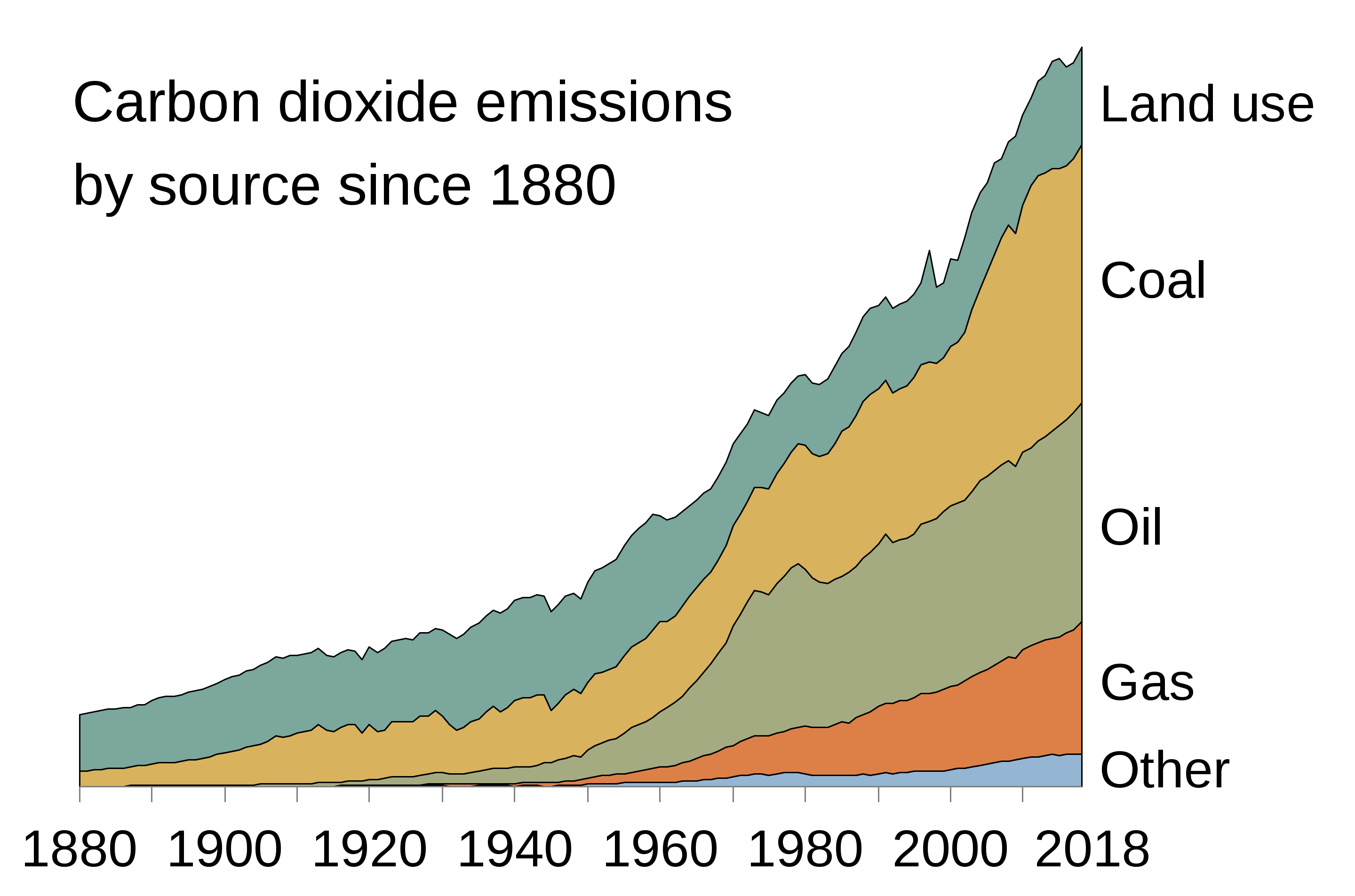

Some climate activists have begun to suggest that for the sake of the environment, we ought to switch from fossil fuels to other energy sources as soon as possible and leave as much as possible of what is left in the ground. The argument against burning the rest of the oil (and coal) is that fossil fuels are one of the biggest contributors of atmospheric carbon that leads to global warming. While this is true, other factors such as deforestation and even agribusiness release comparable amounts of carbon. Simply stopping the use of oil will not solve the whole climate change problem, although it is a key element of the change society needs to make to stabilize the global climate.

But because energy is such a large part of the economies of developed nations, any change is heavily contested. Global energy corporations have an incredible ability to influence politics. A few years ago BP issued an “Energy Outlook” report for the year 2035. BP claimed that Hubbert’s Peak Oil scenario was actually incorrect and announced the company’s intention to burn just as much as possible over the next two decades. BP’s claim that oil production hasn’t peaked, however, depended on redefining the word oil to include both tar sands and biofuels such as ethanol. Ethanol production depends not only on the energy-intensive production of surplus corn and cane sugar (used in Brazil as the primary plant source), but in government subsidies that keep the prices of these commodities below their cost of production. So it’s hard to see how biofuels could legitimately be called a new source of “oil.”

But because energy is such a large part of the economies of developed nations, any change is heavily contested. Global energy corporations have an incredible ability to influence politics. A few years ago BP issued an “Energy Outlook” report for the year 2035. BP claimed that Hubbert’s Peak Oil scenario was actually incorrect and announced the company’s intention to burn just as much as possible over the next two decades. BP’s claim that oil production hasn’t peaked, however, depended on redefining the word oil to include both tar sands and biofuels such as ethanol. Ethanol production depends not only on the energy-intensive production of surplus corn and cane sugar (used in Brazil as the primary plant source), but in government subsidies that keep the prices of these commodities below their cost of production. So it’s hard to see how biofuels could legitimately be called a new source of “oil.”

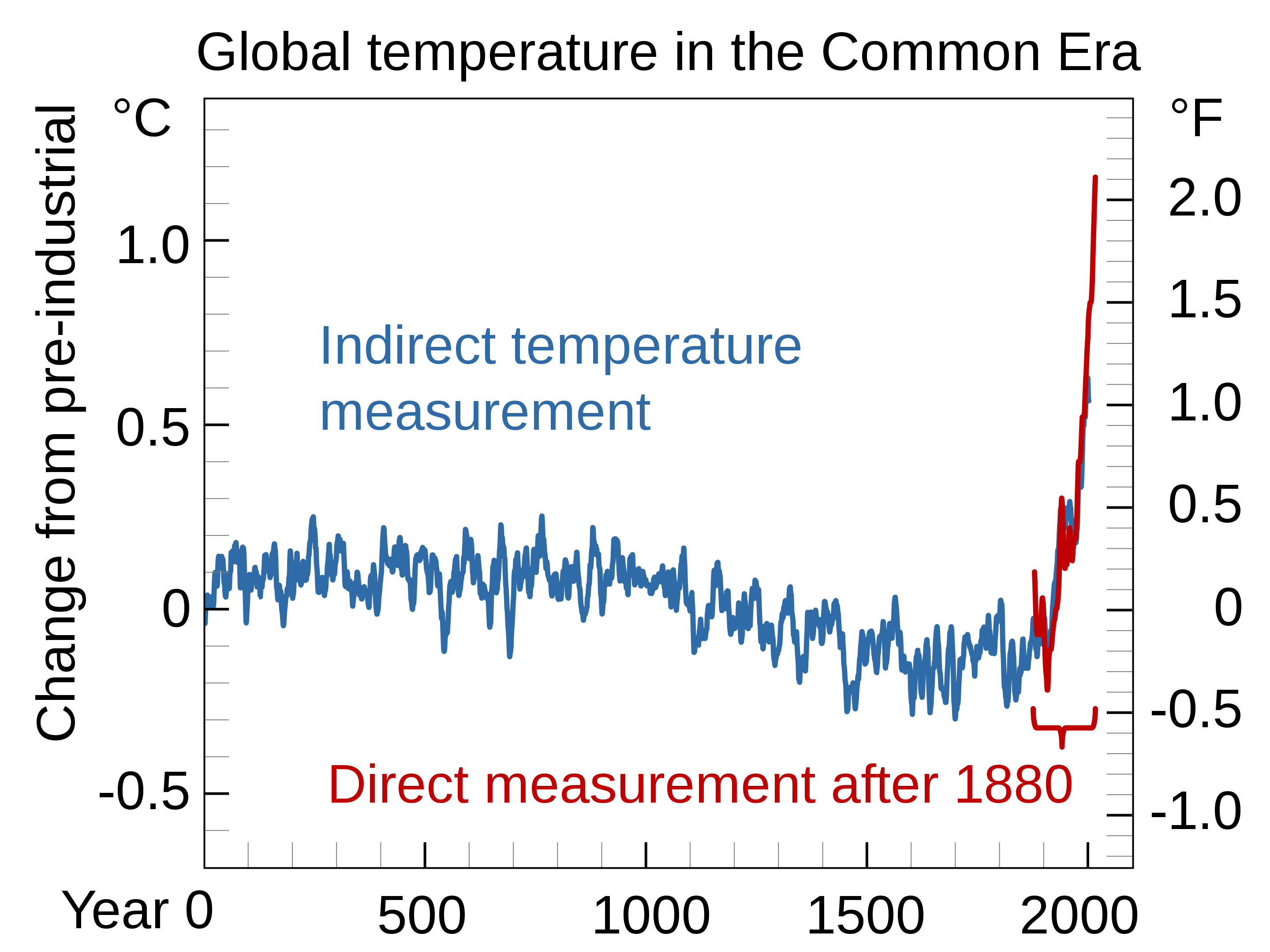

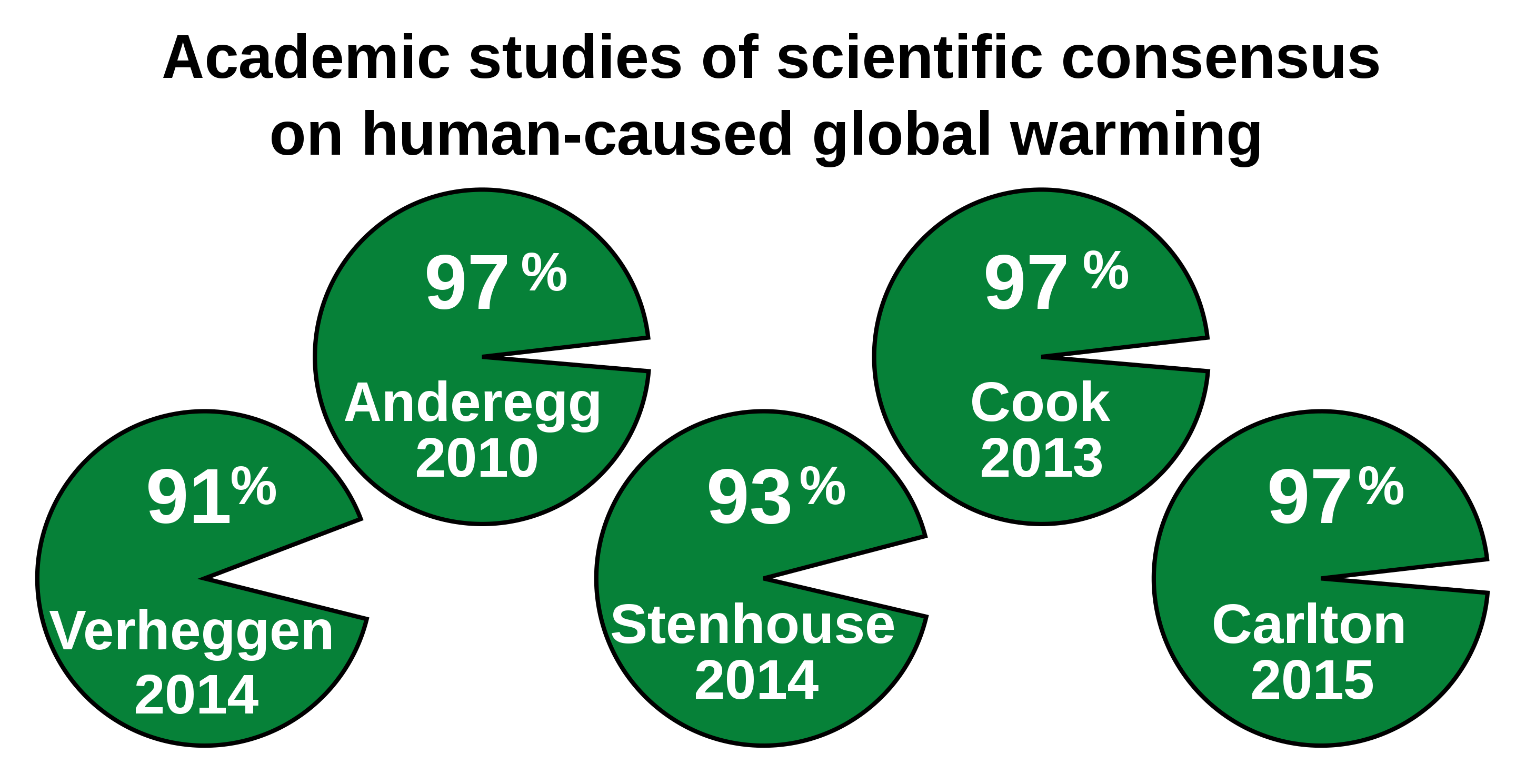

Climate change, more than any other environmental concern, has dominated the attention of Americans in recent years (and has in many cases pushed pollution off the table, which is unfortunate). Although the idea that the planet’s climate has been adversely affected by human activity is very controversial in the media, politics, and popular culture, it is almost universally accepted by scientists. According to NASA, at least 97% of climate scientists agree that global warming over the past couple of centuries is due to human activities, or anthropogenic. American and international science organizations like the American Geophysical Union, the American Meteorological Society, and the American Medical Association, in addition to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, have all gone a step further, agreeing with the American Physical Society, “We must reduce emissions of greenhouse gases beginning now.”

Of course who they mean by “we” is unclear, and the penalties for heeding their warnings are really hard to specify. We often hear that “The forecasts show that it is China, India, and the other emerging economies that are increasing their carbon dioxide emissions at a speed that will cause dangerous climate change. In fact, China already emits more CO2 than the USA, and India already emits more than Germany.” This objection came from a European Union environment minister, speaking at the World Economic Forum at Davos in 2007. The population of China is 1.386 billion. India is 1.339 billion, USA 327 million, Germany 82.79 million. That means that although China emits more total CO2 than the US, on a per-person basis, the U.S. still emit twice as much (15.7 tons per person to China’s 7.7 tons). Similarly, on a per capita basis, Germany emits more (9.7 tons) than China, and five times more than India (1.8 tons per capita). While it’s important for China and India to get their carbon emissions under control, Europe and North America put most of the carbon in the atmosphere.

What about future energy potential from sources that do not damage the environment as fossil fuel carbon emissions can? The chart below gives the reader some idea of what our 2023 energy sources are. These can vary widely by region and country. The reader is encouraged to explore the Our World in Data website on energy mixes for more details on countries and regions breakdown at https://ourworldindata.org/energy-mix

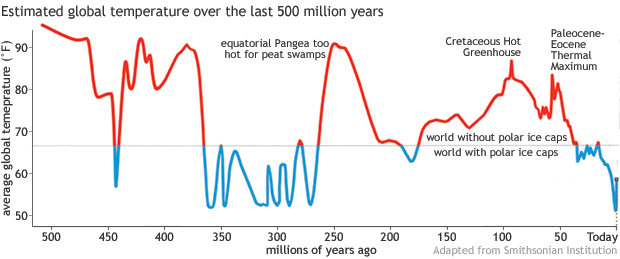

Finally, the reader is encouraged to check the data on the past record of the planet for extreme cooling and heating periods. For instance, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or NOAA, the earth was once covered in ice, snow, and cold around 700 million years ago. The last ice age associated with 20,000 years ago was quite strong. Global average temperatures for the last 500 million years indicate several periods of extremely warm temperatures with averages near ninety degrees for the planet (today the planet is around sixty degrees and rising). Between 250 million and 50 million years ago, the planet was quite warm compared to the modern world, with only a brief period of polar ice caps. Remember, this was the age of dinosaurs (250-65 million years ago roughly). Humans are not dinosaurs! We are not built to take such heat.

Last 500 million years Global Temperature AverageSources:

Scott, Michon. 2023. “What’s the coldest the Earth’s ever been?” NOAA, Climate.gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-qa/whats-coldest-earths-ever-been

Scott, Michon. 2021. “What’s the hottest the Earth’s ever been?” NOAA, Climate.gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-qa/whats-hottest-earths-ever-been

Such extremes of hot and cold average temperatures on the planet lead to extreme sea level changes. Today, over 3 billion people live at risk of such catastrophic sea level changes by proximity to coastal and low-lying areas of land around the earth. Many are in big port cities on lakes, rivers and oceans. Cities such as Venice in Italy are already taken action with huge and costly projects that may or may not work given water elevation rises. The earth is constantly changing in terms of climate, land, weather patterns and more. In the last few thousands of years, giant storm systems such as the monsoons, hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones have dominated how humans adapt along the coasts and waterways of the planet. Now, adaptation to rising water levels will add to the stress of that global adaptation. There will likely be more adaptations needed by humanity as the climate changes. Are you ready, are we ready?

Source: Reimann L, Vafeidis AT, and Honsel LE (2023). “Population development as a driver of coastal risk: Current trends and future pathways. In Cambridge Prisms: CoastalFutures, 1, e14, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2023.3

Knowledge Check:

Are human societies able to continue growing forever, or are there limits to the Earth’s carrying capacity?

- Population Growth & Resource Scarcity

- Why did Malthus worry that overpopulation would lead to chaos?

- What has prevented a Malthusian catastrophe so far?

- Why do you think Melinda Gates felt she needed to set the record straight on population?

- What monocultures do we depend on today that might make us vulnerable, similar to the Irish potato situation in the 19th century?

- Why did Paul Ehrlich’s book possibly do more harm than good?

- Do you think the possibility of social collapse, even if uncertain, is something we should study more closely?

- What did Hubbert mean by an “exponential growth culture”?

- Climate Activism

- Why is atmospheric carbon a global rather than a regional or national problem?

- Why is it misleading to compare current total carbon emissions between countries in trying to assess “blame”?

- How does politicizing the climate debate make it more difficult to find solutions?

- What motivates some organizations to resist the idea that humans have caused global warming?

- Would addressing climate change more rapidly hurt or help the global economy?

This is an adaptation from Modern World History (on Minnesota Libraries Publishing Project) by Dan Allosso and Tom Williford, and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.