An Introduction to Human Biology

3 Anatomical Terminology: Developing a Common Language

Anatomists and healthcare providers use terminology that can be bewildering to the uninitiated. However, the purpose of this language is not to confuse but rather to increase precision and reduce medical errors. For example, is a scar “above the wrist” located on the forearm two or three inches away from the hand? Or is it at the base of the hand? Is it on the palm side or the back side? By using precise anatomical terminology, we eliminate ambiguity. Anatomical terms derive from ancient Greek and Latin words. Because these languages are no longer used in everyday conversation, the meaning of their words does not change.

Anatomical terms are made up of roots, prefixes, and suffixes. The root of a word often refers to an organ, tissue, or condition, whereas the prefix or suffix often describes the root. For example, in the disorder hypertension, the prefix “hyper-” means “high” or “over,” and the root word “tension” refers to pressure, so the term “hypertension” refers to abnormally high blood pressure.

Anatomical Position

Learning Objective

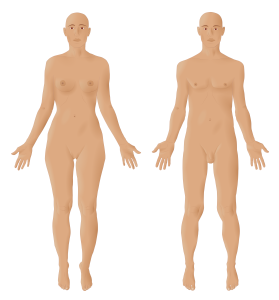

To further increase precision, anatomists standardize how they view the body. Just as maps are typically oriented with north at the top, the standard body “map,” or anatomical position, is that of the body standing upright, with the feet at shoulder width and parallel, toes forward. The upper limbs are held to each side, and the palms of the hands face forward, as illustrated in the figure to the left. Using this standard position reduces confusion. It does not matter how the body being described is oriented; the terms are used as if it is in anatomical position. For example, a scar in the “anterior (front) carpal (wrist) region” would be present on the palm side of the wrist. The term “anterior” would be used even if the hand were palm down on a table. It is also critical to realize that if you label the left or right side of a structure (or person), the left and right are reversed.

A body that is lying down is described as either prone or supine. Prone describes a face-down orientation, and supine describes a face-up orientation. These terms are sometimes used in describing the body’s position during specific physical examinations or surgical procedures.

Directional Terms

Learning Objective

You can use descriptive terms to pinpoint an anatomical location further. These terms are used to describe a location in relation to other structures. Some of them may be terms you have heard in everyday conversation; a lateral pass in football, for example, is a pass toward the sideline.

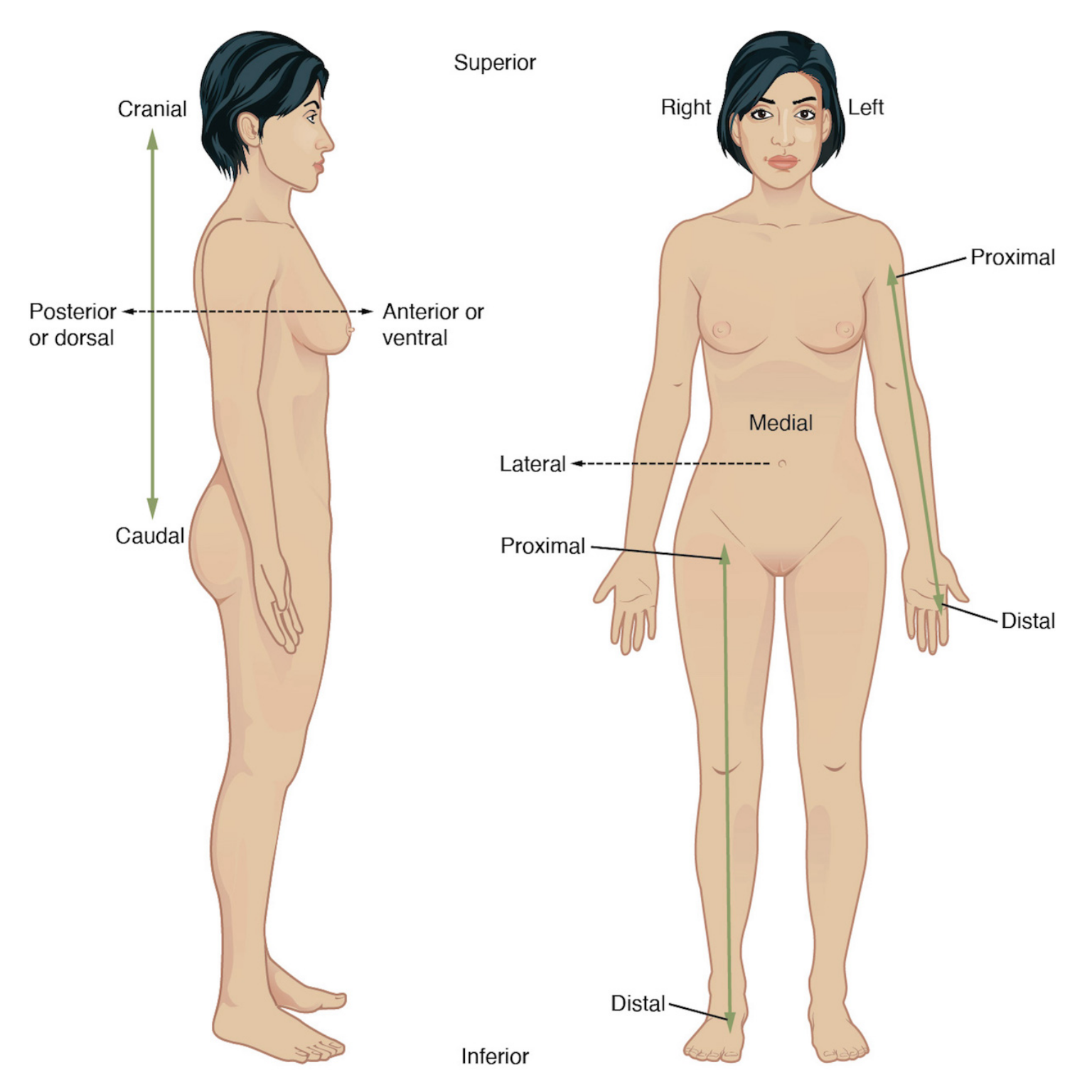

Superior and Inferior, Anterior and Posterior, and Ventral and Dorsal

The first directions we will explore are superior, inferior, anterior, posterior, ventral, and dorsal. In humans, which stand upright on two feet, other terms are synonymous with these four terms. For example,

- Cephalic means toward the head and is the same as superior for a human in anatomical position;

- Caudal means toward the tail, or the same as inferior for a human in anatomical position;

- Posterior means toward the back, so posterior and dorsal are in the same direction. (This would not be true for a four-legged animal, such as a rat or cat you might dissect in the lab.),

- Anterior means toward the belly, so anterior and ventral are in the same direction for a human in anatomical position.

Note that left and right are reversed if you examine a figure from the anterior view.

Medial and Lateral

Next, we will discuss terms that relate structures to the midline. These are medial, lateral, and intermediate.

- Medial describes the middle or a direction toward the middle of the body. The (big toe) is the medial toe. For example, the “belly button” is inferior to and medial to the nipples.

- Lateral describes a direction toward the side of the body, away from the midline. The term can be modified by the addition of prefixes.

- The prefix “contra” means opposite, so saying that one organ is contralateral to another means it is on the opposite side of the body. For example, the liver is contralateral to the stomach.

- The prefix “ipsi” means “same,” so describing two structures as ipsilateral means they are on the same side of the body. For example, the pancreas is ipsilateral to the stomach.

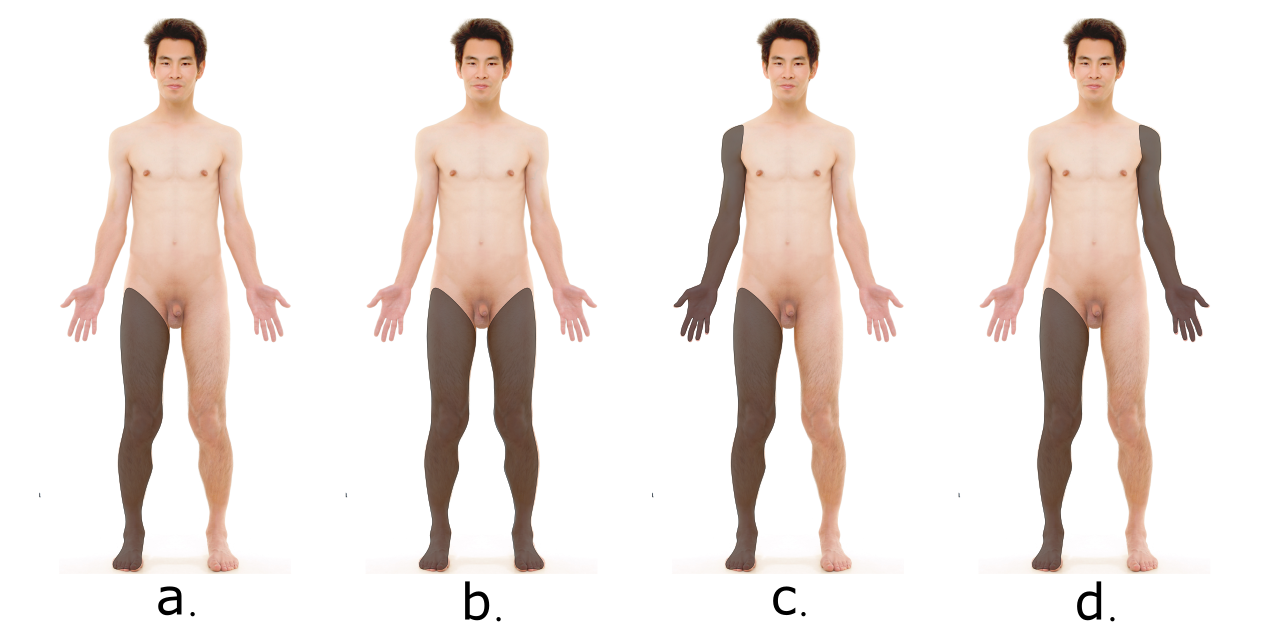

- The prefix “uni” means one while “bi” means two. So, for example, a problem that affects one leg is unilateral. If both legs are affected, the problem is bilateral.

- Intermediate describes a position “in between” two other structures. For example, the heart is intermediate to the lungs.

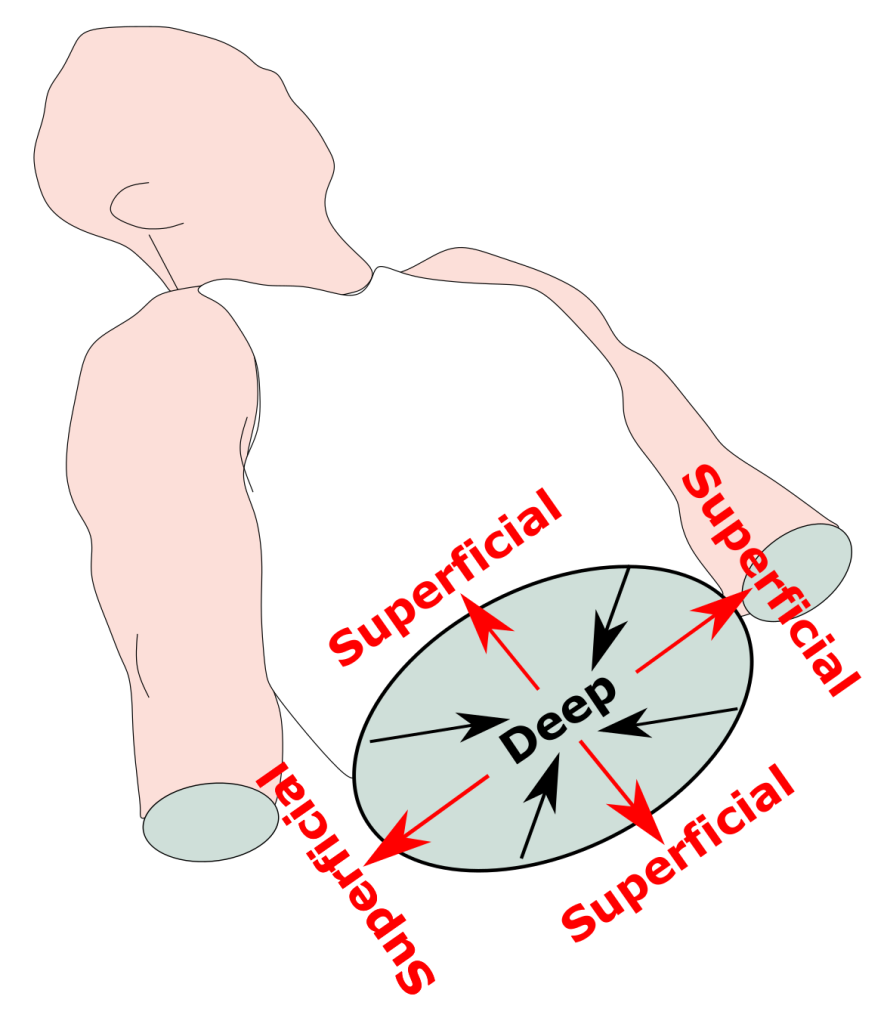

Proximal, Distal, Superficial, Deep

The terms proximal and distal are only used when referring to appendicular body parts (arms and legs). Superficial and deep refer to a position in the body relative to its external surface.

- Proximal describes a position in a limb nearer to the point of attachment or the body’s trunk. For example, the thigh is proximal to the knee.

- Distal describes a position in a limb farther from the point of attachment or the body’s trunk. For example, the knee is distal to the thigh.

- Superficial describes a position closer to the surface of the body. For example, the skin is superficial to the bones.

- Deep describes an internal position farther from the surface of the body. For example, the brain is deep to the skull.

Learn By Doing 3.1

Examine the figure on the left; in which direction is the arrow pointing?

Examine the figure on the left; in which direction is the arrow pointing?

- inferiorly

- superiorly

- anteriorly

- posteriorly

Hint: The arrow points toward the back or behind this figure in anatomical position.

When considering the trunk as the origin, the knee would be considered ________________ to the ankle.

- Deep

- Distal

- Proximal

- Superficial

Hint: Remember that depending on the origin, the answers could differ, so keep in mind that the starting position is the trunk.

A patient is in the operating room for repair of a fracture of the femur (thigh bone ). The surgeon will repair the fracture by placing a metal rod into the femur to support the broken portion. The radiologist has informed you that the break is in the distal part of the femur. Where should the rod be placed to support the fractured bone?

| Directional Term | Meaning |

| superior | above (or toward the head) |

| inferior | below (or toward the feet) |

| distal | farther from the trunk or origin |

| proximal | closer to the trunk or origin |

| superficial | toward or on the surface |

| deep (internal) | away from the surface |

| anterior | toward the front (or toward the belly) |

| ventral | toward the front (or toward the belly) |

| posterior | toward the rear (or toward the back) |

| dorsal | toward the rear (or toward the back) |

| medial | toward the midline |

| lateral | toward the side |

Table 3.1 lists all the human anatomical directions we discussed. In the following sections, you will practice using these planes and directional terms when describing the locations of organs and organ systems.

Directional anatomical terms appear throughout this and any other anatomy textbook. These terms are essential for describing the relative locations of different body structures. For instance, an anatomist might describe one band of tissue as “inferior to” another, or a physician might describe a tumor as “superficial to” a deeper body structure. Commit these terms to memory to avoid confusion when studying or describing the locations of particular body parts.

Body Planes

Learning Objective

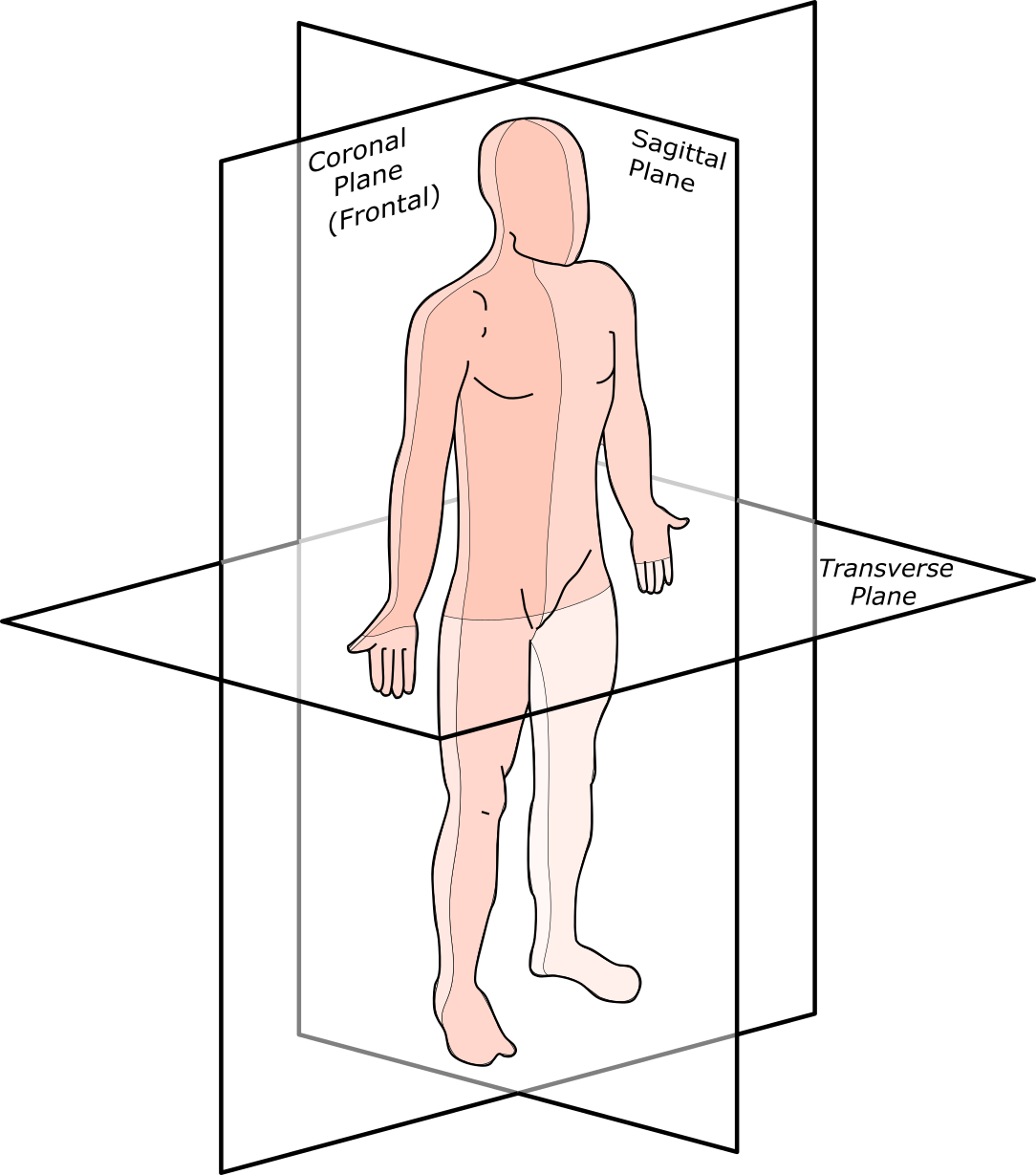

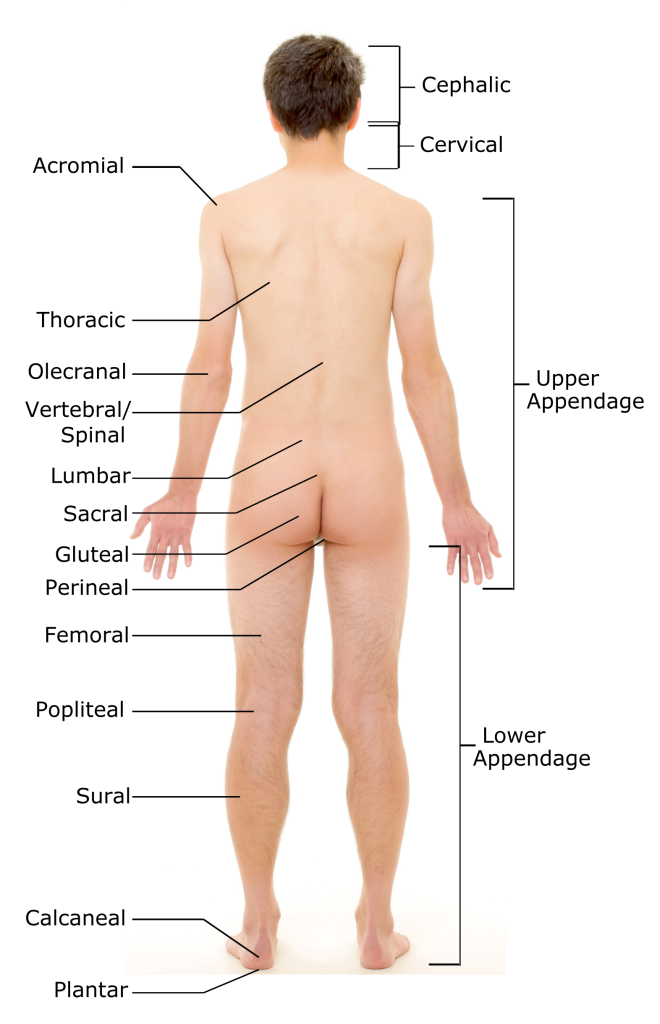

To better identify the locations of the organs that contribute to vital functions, you need some reference points for description. To serve that function, we will now define different planes of the body. A plane is an imaginary flat surface that runs through the body in different directions. Medical professionals use them to examine various internal body parts. Directional orientation is another anatomical tool that describes how body parts are related.

Each organ system spans large regions of the human body. It is helpful, therefore, to establish reference planes and directions that can help us describe specific locations of structures as we discuss them. To ensure everyone is talking about the same thing, anatomists and physiologists often refer to anatomical position and the body planes that penetrate it. As we’ve discussed, anatomical position describes a person standing upright, with the arms at the sides and the palms facing forward (as demonstrated in the image below). Body planes (a plane is a flat, two-dimensional surface) are imaginary surfaces that run through the body and divide it into different sections s. We can talk about a specific location using the planes as reference points within the anatomical position.

An infinite number of planes run through the human body in all directions. However, we will focus on the three traditionally used planes when discussing human anatomy. First is the transverse plane (also called the horizontal plane), which divides the body into top and bottom. In anatomical position, transverse planes are parallel to the ground. In humans, the transverse plane separates the superior from the inferior, or put another way, the head from the feet.

The second is the coronal plane, which is a vertical plane that divides the body into the front and back sections. If you do a “belly flop” into the water, you sink into the water via the coronal planes. A coronal (also known as frontal or lateral) plane runs at a right angle (perpendicular) to the ground; in humans, it separates the front from the back, the anterior from the posterior, and the ventral from the dorsal.

The sagittal plane divides the body into left and right sections with a vertical plane that passes from the front to the rear. The midsagittal or median plane is in the midline; i.e., it would pass through midline structures such as the navel or spine, and all other sagittal planes (also referred to as parasagittal planes) are parallel to it. Median can also refer to the midsagittal plane of other structures, such as a digit.

As you might imagine, it is possible to cut a body structure at an angle other than parallel or perpendicular to the ground. These “angled” sections are referred to as oblique. One way to recognize an oblique section is that bilateral structures will not appear the same size in the section.

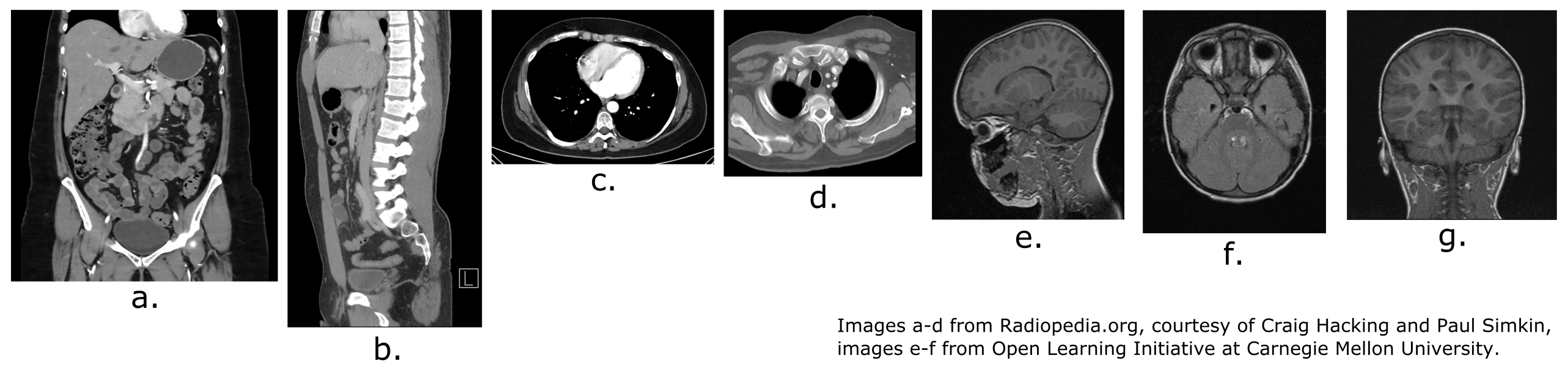

Many imaging modalities used in medicine (CT scans, MRI scans, and ultrasounds) allow us to view the body in cross-section. The three main planes described above are used to orient and describe where the cross-section is and how it passes through the body. Imagine a person in anatomical position and an X-Y-Z coordinate system with the y-axis going from front to back, the x-axis going from left to right, and the z-axis going from up to down.

Learn By Doing 3.2

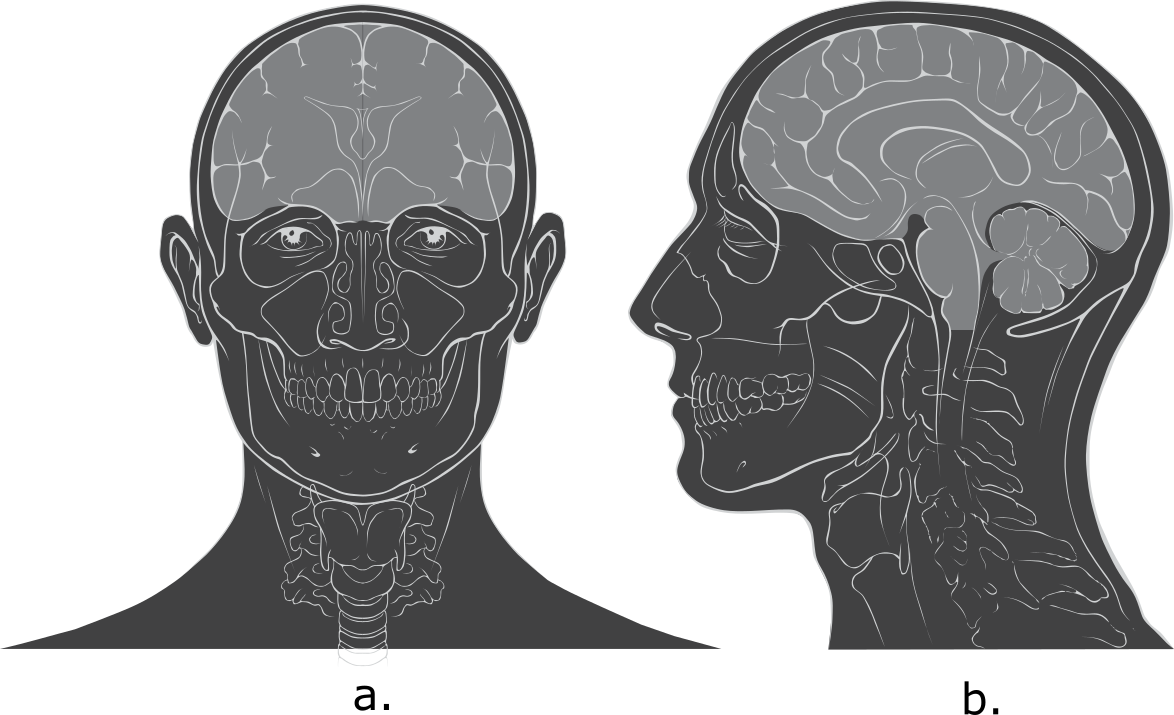

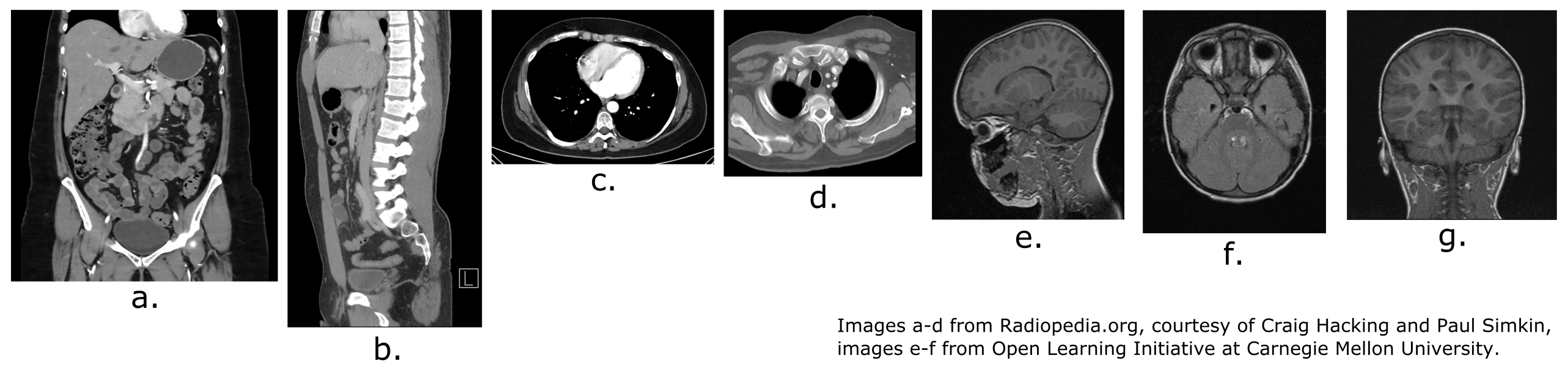

The images below are from scans of the head and body, showing all three planes of section and an oblique section. These images can sometimes be reconstructed in a computer to show the same body in a different plane, making some features of the body easier to see.

What planes are shown in the scans below?

Describing Parts of the Body

Terms for Regional Anatomy

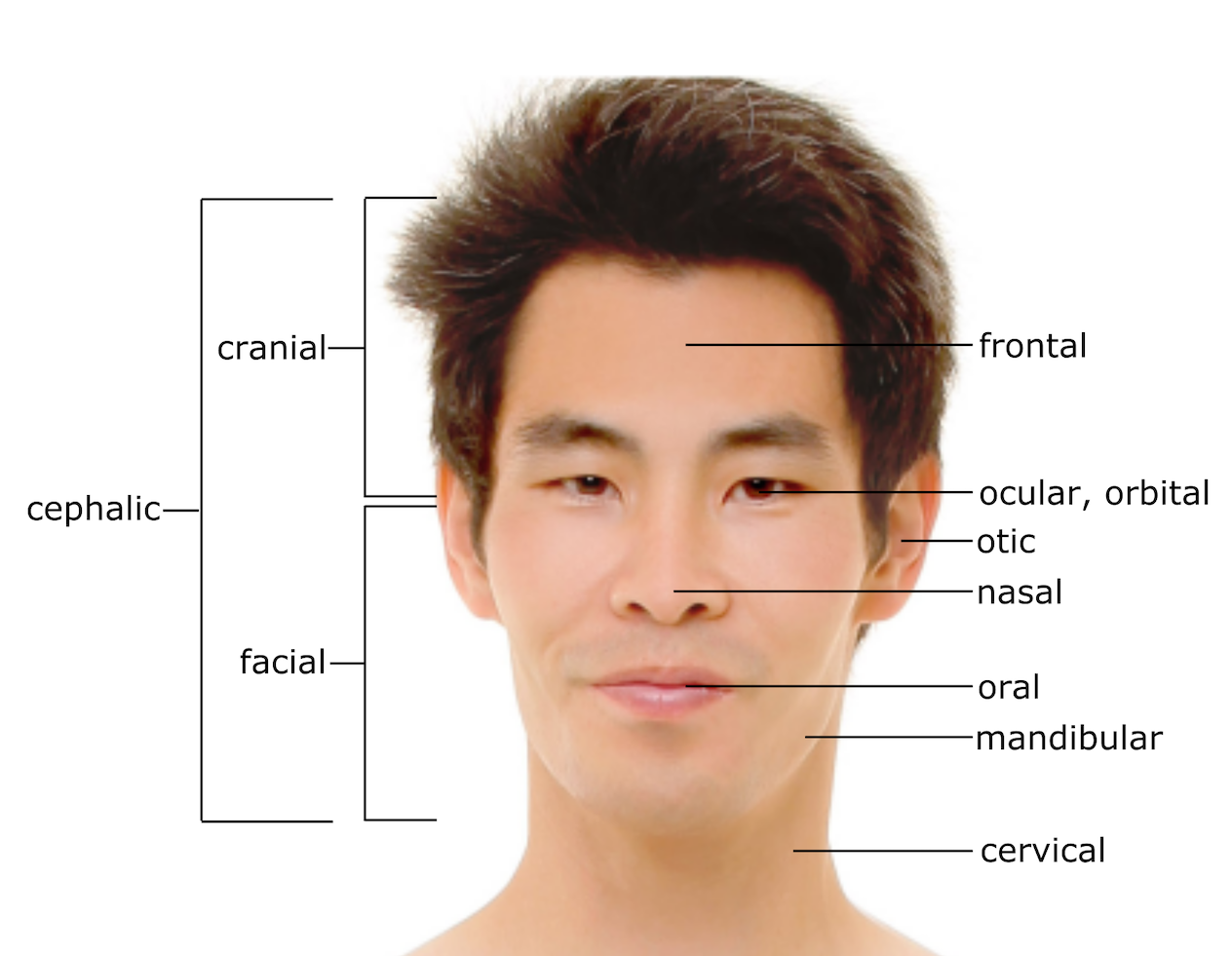

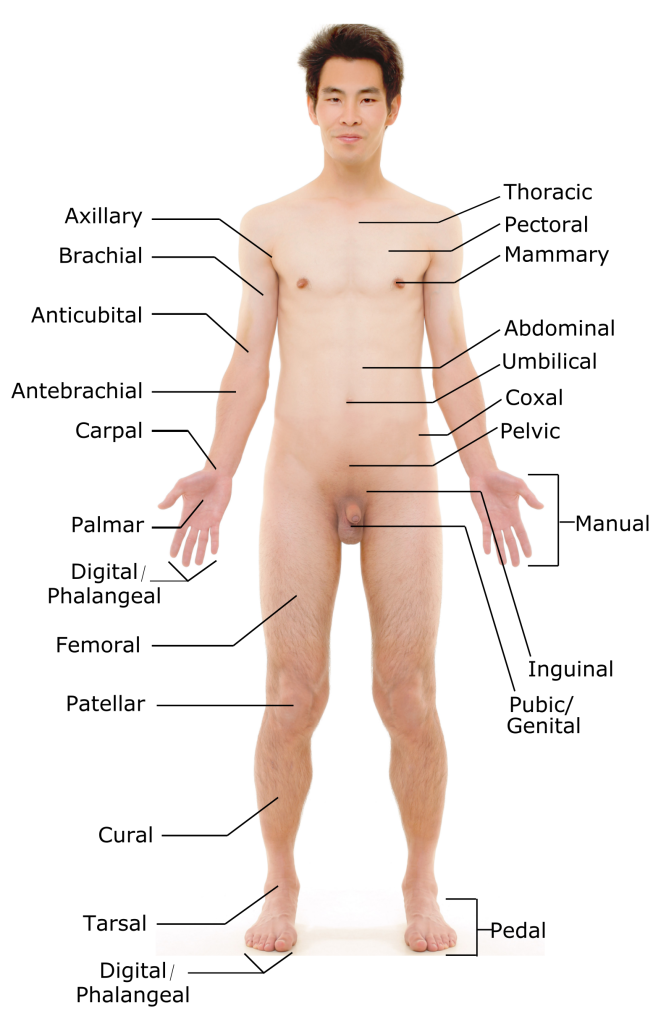

The human body’s numerous regions have specific terms to help increase precision and accuracy. We will review the terms describing both the anterior and posterior surfaces of the body. Let’s begin with the ventral or anterior body surface.

Anterior View

The cranial region includes the upper part of the head, while the facial region encompasses the lower half of the head beginning below the eyes. The cephalic region includes both cranial and facial regions. The area above the eyes is described with the word frontal. The area of the eyes is referred to as the ocular or orbital region. The cheek region is referred to as the buccal region. The ears are referred to as the aural or otic region. The nose area is referred to as the nasal region. The jaw area is referred to as mandibular while the area of the mouth is the oral region. The neck (anterior and posterior) is referred to as the cervical region.

The anterior torso or trunk of the body contains, from superior to inferior, the thoracic region encompassing the chest, the mammary region encompassing each breast, the abdominal region encompassing the stomach area, and the coxal region encompassing the hip area. The umbilical area is located at the center of the abdomen.

The anterior surface of the pelvis and legs contains, from superior to inferior, the inguinal or groin region between the legs and genitals, the pubic/genital region surrounding the genitals, the femoral region encompassing the thighs, the patellar region encompassing the knee, the crural region encompassing the lower leg, the tarsal region encompassing the ankle, the pedal region encompassing the foot, and the digital/phalangeal region encompassing the toes.

The anterior regions of the upper limbs, from superior to inferior, are the axillary region encompassing the armpit, the brachial region encompassing the upper arm, the antecubital region including the front of the elbow, the antebrachial region encompassing the forearm, the carpal region encompassing the wrist, the palmar region encompassing the palm, and the digital (phalangeal) region encompassing the fingers. The term manual refers to the entire hand, anterior and posterior.

Posterior View

The posterior view of the trunk contains, from superior to inferior, the cervical region encompassing the neck, the thoracic region encompassing the upper back, the lumbar region encompassing the lower back, and the sacral region just above the tailbone. The term dorsal also may be applied to the posterior surface of the upper back.

The regions of the back of the arms, from superior to inferior, include the acromial region encompassing the shoulder, the brachial region encompassing the upper arm, the olecranal region encompassing the back of the elbow, the antebrachial region encompassing the back of the arm.

The posterior regions of the legs, from superior to inferior, include the gluteal region encompassing the buttocks, the femoral region encompassing the thigh, the popliteal region encompassing the back of the knee, the sural region encompassing the back of the lower leg, the calcaneal region which contains the heel, and the plantar region encompassing the sole of the foot.

Some regions described above are combined into larger regions. These include the trunk or torso region which is a combination of the thoracic, mammary, abdominal, naval, and coxal regions. The cephalic region is a combination of all the head regions. The term appendage refers to a structure that protrudes from the torso. The upper appendage region is a combination of all of the arm regions. The lower appendage region is a combination of all leg regions. When describing an appendage we may use the term appendicular.

With practice, you can describe the body’s regions using appropriate anatomical terminology. Many of these descriptive terms are repeated in the names of different body structures. For example, the term femoral is used to describe the thigh region. The bone in the thigh is called the femur; the artery that serves the thigh is called the femoral artery; the group of skeletal muscles that move the thigh is named the quadriceps femoris. So, although it may seem that there are more terms than you might ever be able to remember, learning these descriptive terms early in your study of the body will pay off later.

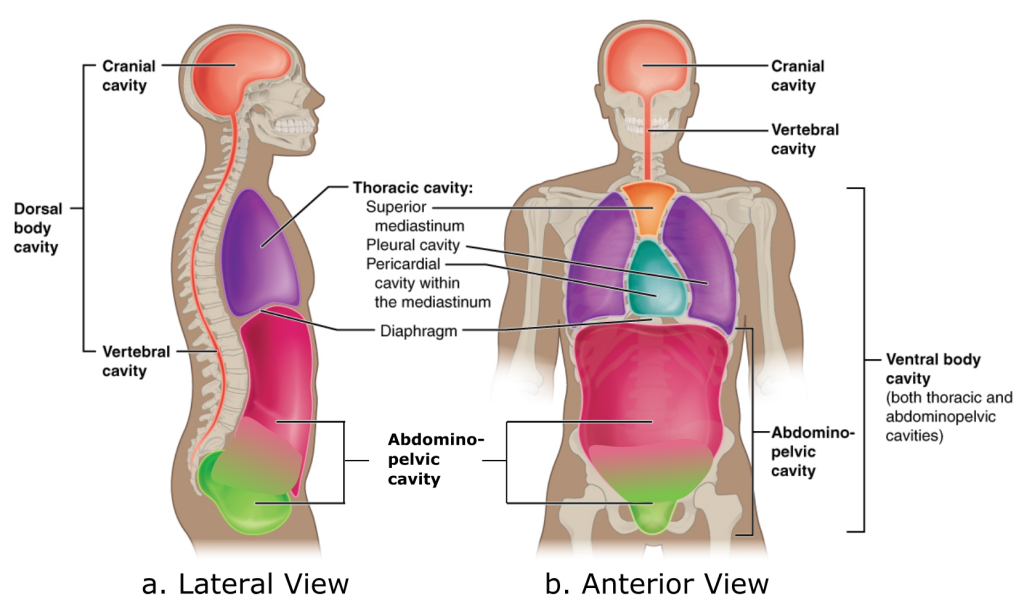

Body Cavities and Serous Membranes

The body maintains its internal organization using membranes, sheaths, and other structures that separate compartments. The dorsal cavity and the ventral cavity are the largest body compartments. These cavities contain and protect delicate internal organs, and the ventral cavity allows for significant changes in the size and shape of the organs as they perform their functions. For example, the lungs, heart, stomach, and intestines can expand and contract without distorting other tissues or disrupting the activity of nearby organs.

The dorsal and ventral cavities are each subdivided into smaller cavities. In the posterior (dorsal) cavity, the cranial cavity houses the brain, and the spinal cavity (or vertebral cavity) encloses the spinal cord. Just as the brain and spinal cord make up a continuous, uninterrupted structure, the cranial and spinal cavities that house them are also continuous. The brain and spinal cord are protected by the bones of the skull and vertebral column and by cerebrospinal fluid, a colorless liquid produced by the brain, which cushions the brain and spinal cord within the dorsal cavity.

The ventral cavity has two main subdivisions: the thoracic cavity and the abdominopelvic cavity. The thoracic cavity is the superior subdivision of the ventral cavity, and the rib cage encloses it. The thoracic cavity contains the lungs and the heart. The diaphragm (a large skeletal muscle) forms the floor of the thoracic cavity and separates it from the inferior abdominopelvic cavity. The abdominopelvic cavity is the largest in the body. Although no membrane physically divides the abdominopelvic cavity, it can be useful to distinguish between the abdominal cavity, the division that houses the digestive organs, and the pelvic cavity, the division that houses the organs of reproduction.

Membranes of the Ventral Body Cavity

A serous membrane (also referred to as a serosa) is one of the thin membranes that cover the walls and organs in the thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities. The parietal layers of the membranes line the walls of the body cavity. The visceral layer of the membrane covers the organs (the viscera). A very thin, fluid-filled serous space, or cavity, is between the parietal and visceral layers.

There are three serous cavities with associated membranes. The pleura are the serous membrane that enclose the pleural cavity; the pleural cavity surrounds the lungs. The pericardium is the serous membrane that encloses the pericardial cavity; the pericardial cavity surrounds the heart. The peritoneum is the serous membrane that encloses the peritoneal cavity; the peritoneal cavity surrounds several organs in the abdominopelvic cavity. The serous membranes form fluid-filled sacs, or cavities, that cushion and reduce friction on internal organs when they move, such as when the lungs inflate or the heart beats. The parietal and visceral serosa secrete the thin, slippery serous fluid within the serous cavities. The pleural cavity reduces friction between the lungs and the body wall. Likewise, the pericardial cavity reduces friction between the heart and the pericardium wall. The peritoneal cavity reduces friction between the abdominal and pelvic organs and the body wall. Therefore, serous membranes provide additional protection to the viscera they enclose by reducing friction that could lead to inflammation of the organs.

Did I Get This? 3.1

What is the body’s position in the “normal anatomical position?”

- The person is prone with upper limbs, including palms, touching sides and lower limbs touching at sides.

- The person is standing facing the observer, with upper limbs extended out at a ninety-degree angle from the torso and lower limbs in a wide stance with feet pointing laterally.

- The person is supine with upper limbs, including palms, touching sides and lower limbs touching at sides.

- None of the above

To make a banana split, you halve a banana into two long, thin, right and left sides along the ________.

- coronal plane

- midsagittal plane

- transverse plane

The lumbar region is ________.

- inferior to the gluteal region

- inferior to the umbilical region

- superior to the cervical region

- superior to the popliteal region

The heart is within the ________.

-

- cranial cavity

- thoracic cavity

- posterior (dorsal) cavity

- All of the above

If a bullet were to penetrate a lung, which three anterior thoracic body cavities would it enter, and which layer of the serous membrane would it encounter first?

*

“Learn By Doing” and “Did I Get This?” Feedback

Learn By Doing 3.1

Examine the figure. Which direction is the arrow pointing?

Examine the figure. Which direction is the arrow pointing?

- inferiorly

No: In directional terminology, an arrow pointing in an inferior direction would be pointing down. - superiorly

No: In directional terminology, an arrow pointing in a superior direction would be pointing up. - anteriorly

No: This answer is close in orientation but in the opposite direction. - posteriorly

Yes: The arrow points to the posterior (back) of the body.

When considering the trunk as the origin, the knee would be considered ________________ to the ankle.

- Deep

No: The knee is nearer the trunk (origin) than the ankle, so the answer is the opposite of distal. - Distal

No: Your answer is close in orientation but in the opposite direction. - Proximal

Yes: The knee is nearer the trunk (origin) than the ankle, making it proximal. - Superficial

No: Superficial is the opposite of deep and refers to an outer surface, such as the outside of the body or an organ.

A patient is in the operating room for repair of a fracture of the femur (thigh bone). The fracture will be repaired by placing a metal rod into the femur to support the broken portion. The radiologist has informed you that the break is in the distal part of the fem r. Where should the rod be placed to support the fractured bone?

- Distal means away from the trunk of the body. Therefore, the fracture is in a part of the femur closer to the knee, beyond the halfway point.

- In this scenario, the physician indicates a starting point of the knee and moves toward the trunk.

Learn By Doing 3.2

The images below are from scans of the head and body, showing all three planes of section and an oblique section. These images can sometimes be reconstructed in a computer to show the same body in a different plane, making some features of the body easier to see.

What planes are shown in the scans below?

a. Coronal (frontal), dividing the body front to back; b. sagittal, diving the body left to right; c. transverse, dividing the body top to bottom; d. oblique transverse, asymmetrically diving the body top to bottom; e. sagittal, dividing the head left to right; f. transverse, dividing the head from top to bottom; and g. frontal (coronal), dividing the head back to front

Did I Get This? 3.1

What is the body’s position in the “normal anatomical position?”

- The person is prone with upper limbs, including palms, touching sides and lower limbs touching at sides.

No: Upper limbs are held slightly out to the side, the lower limbs are slightly separated, and the palms face out. - The person is standing facing the observer, with upper limbs extended out at a ninety-degree angle from the torso and lower limbs in a wide stance with feet pointing laterally.

No: Upper limbs are only held slightly out to the side. - The person is supine with upper limbs, including palms, touching sides and lower limbs touching at sides.

No: Palms should face forward. - None of the above

Correct: In anatomical position, a person is shown standing upright, with the feet shoulder-width apart and parallel to each other, with the toes pointing forward d. The upper limbs are held out slightly to the side, and the palms of the hands face forward.

To make a banana split, you halve a banana into two long, thin, right and left sides along the ________.

- coronal plane

No: the coronal plane separates the body front to back. - midsagittal plane

Yes: the sagittal plane separates a structure’s right and left sides. - transverse plane

No: the transverse plane separates the body from top to bottom.

The lumbar region is ________.

- inferior to the gluteal region

No: the lumbar region is superior to the buttocks. - inferior to the umbilical region

No: the lumbar region is posterior to the umbilical region. - superior to the cervical region

No: the lumbar region is inferior to the neck. - superior to the popliteal region

Yes: the lumbar region is superior to the back of the knee.

The heart is within the ________.

- cranial cavity, thoracic cavity, dorsal cavity

- All of the above

If a bullet were to penetrate a lung, which three anterior thoracic body cavities would it enter, and which layer of the serous membrane would it encounter first?

The bullet would penetrate the ventral cavity, the thoracic cavity, and the pleural cavity in that order. It would penetrate the parietal layer of serous membrane and then the visceral layer of serous membrane before entering the lung.

Media Attributions

- Female-male_front-back_3d-shaded_human_illustration © Goran tek-en adapted by C. Seiwert is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- directional terms © Open Stax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- ipsi contra © Mikael Häggström adapted by C. Seiwert is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- superficial deep adapted by C. Seiwert is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- posterior

- 3.5 Anatomical_Planes-en copy 2 © Edoarado adapted by C. Seiwert is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 3.6 edit Head_anatomy_anterior_lateral_views_edit © Patrick J. Lynch adapted by C. Seiwert is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- LBD3.2_1 adapted by C. Seiwert is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- head3 adapted by C. Seiwert is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3.8anterior adapted by C. Seiwert is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3.9posterior adapted by C. Seiwert is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3.10 body cavities corrected © Open Stax adapted by C. Seiwert is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license