5 A Creative Workshop Model

For Understanding Climate Activism as Custodianship of Country

Dr. Caelli Jo Brooker; Dr. Michelle Catanzaro; and Madison Shakespeare

Abstract

This reflective case study offers practice-based evidence for the amplification of Indigenous voices in climate action conversations and the Indigenisation of design-based approaches to conceptualising environmental responsibilities. Whilst we are all impacted by the Climate Crisis, First Peoples are disproportionately affected by climate change. Respect for the place-based knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples is essential in educational approaches for healthy climate futures and can help us understand and advocate for protection and care of Country, enact immediate positive change, and advance the call for climate justice.

Reflecting on a First Nations’ artist-led workshop approach, this chapter explores the impact of Indigenous perspectives in facilitating young people to express or translate their complex concerns regarding the climate crisis through visual communication. This chapter discusses the visual methods and processes adopted to run the workshop that brought together First Nations artists, First Nations young people and cultural allies to share their stories about the individual and collective impacts of the climate crisis. By engaging visual communication methods, the stories that emerged culminated in a series of impactful protest posters that utilised traditional and contemporary materials for the creative communication of climate custodianship. Through establishing the application of a combination of visual communication processes and visual yarning, we offer alternative approaches and ways to understand and shape climate education.

This case study first presents reflective insights about the workshop design and creative processes used to engage young people in climate action projects. Secondly, it draws on the lessons learnt throughout this process, and shapes them thematically through analysis to offer recommendations and strategies for future engagement.

Keywords: Indigenous-led, visual communication, youth, climate, Country, custodianship, Indigenous, visual yarning, First Nations perspectives, design, activism,

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander audiences should be aware that the following information may contain the names of deceased persons.

In this paper, we address notions of climate change and climate action. Use of these terms is premised on the idea that we cannot have climate justice without First Nations justice and this includes processes of decolonisation and returning the land to traditional owners who have looked after and cared for Country for tens and thousands of years.

Background

Since 2018, students worldwide have taken part in school strikes to protest against the lack of action on climate change, through the School Strike 4 Climate and Fridays for Future movement. The strikes are visually impactful, with young participants holding placards that convey their key concerns about climate justice through images and text. While the majority of attendees are school students demanding action to combat climate inaction, the visual messages presented at these strikes reveal other important alliances and themes. In Australian events, Indigenous activism, awareness, and representation are recurrently featured. This visibility highlights the personal nature of politics, and the challenges that many First Nations Communities face when confronted with the escalating issues associated with the climate crisis.

The abundance of visual imagery used in these strikes draws attention to the crucial role that visual communication plays in activism and public discourse. This highlights the increasing visual literacies of a young generation concerned with climate issues (Catanzaro & Collins, 2020). The slogans, banners, and placards that speak to Climate Custodianship, Indigenous rights, climate justice, and Care for Country offer valuable insights into young people’s attitudes, opinions, fears, and concerns about climate change viewed through the lens of Aboriginality. Whilst there are First Nations references within the placards, banners and flags at the school strikes (see Shakespeare et. al forthcoming, 2023), the quantity and representation is, at times, limited. Further, the signage that is most commonly seen centres on a generalised call to action, infrequently connecting broader Indigenous issues with the specificity of place and/or language pertinent to caring for Country.

These observations became the motivation for the researchers to explore First Nations focused climate action messaging in a creative workshop environment. In this case study we first outline the goals for the project and how we designed and delivered the creative workshop. Following this, we reflect on our processes, successes and experiences, and offer strategies for increased culturally supported learning in the future.

Project Description

In 2022, a multidisciplinary team of researchers and practitioners conceptualised, designed and implemented an Indigenous-Led workshop at Western Sydney based arts organisation Urban Theatre Projects (UTP) located on the land of the Darug People.

This workshop sought to explore how a participatory experience of cultural education and creative generation can evoke transformative change for climate action.

Young people’s leadership and participation in political movements, such as the School Strike for Climate protests, indicates they are interested, active and want to be involved in addressing some of the biggest issues our societies face (Collin, et. al 2022). Emerging literature (Besant & Pickard, 2021) continues to debunk the idea that young people are politically disengaged and politically apathetic. By utilising a visual, arts-based approach (Finley, et al, 2020) we are advancing the theory that young people are in fact political, but in ways that are less traditional and ways that are more “expressive” and more “emotional” (Muxel, 2010). This project realises a significant opportunity to move beyond an understanding of young people as the targets of communication on climate change – and proposes a format to publicly recognise them as producers of visual, cultural and expressive content.

The aim of the workshop (and the broader project) was to explore the nexus of Indigenous-led Youth Participation, Custodianship of Country, Climate Justice and Culturally-led activism. This workshop was positioned to explore the ways that ‘acts of making’ using visual communication can be more relatable and accessible to multiple audiences whilst questioning how Indigenous-led storytelling, visual practice, and shared processes of making, respectfully proposed in our project as ‘visual yarning’, can be utilised for reflective learning in classrooms. In exploring the foundation, co-production, and creative curation of contemporary visual and multimodal strategies representing Climate Justice and Custodianship of Country and Climate, youth participants were able to present their knowledge and perspectives in accessible formats over which they have personal and cultural sovereignty.

The workshop brought together academic and practical expertise from diverse fields such as Aboriginal Studies, Design, Communication, and Visual Arts. This project connected Western Sydney’s cultural sector through an Industry partnership with UTP. UTP has been at the forefront of creative and social change in Western Sydney as a socially responsive, intersectional, and inclusive arts organisation that reflects the diversity of the West. UTP’s involvement assured that students were exposed to a production model that emphasised self-determination, and the development of accessible, artist and community-led projects.

Workshop Objectives

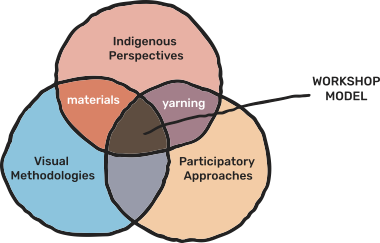

An essential goal of the workshop was Indigenous knowledge sharing, synthesised for the creation of themed visual outcomes, generated through participation and creative engagement. There was a focus on integrating Indigenous knowledges and visual methodologies through participatory approaches, exposing youth undertaking the workshop to the knowledge and expertise of Aboriginal arts practitioners and community Elders. Another objective was to provide participants with an opportunity to engage in participatory creative practice for cultural action and to share their nuanced and individual experiences of climate change, through their own lens of Aboriginality or Allyship.

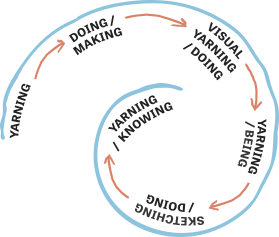

This workshop also aimed to generate creative outcomes with messaging that was specific to each individual, developed through a process of ‘visual yarning’ and reflexive practice. Visual yarning speaks to a relational process of visual knowledge translation and generation that is respectfully informed by yarning as the culturally specific practice of conversation and knowledge sharing well-documented in Australian Aboriginal contexts. Although visual elements are sometimes included in established yarning circle protocols, our objective with visual yarning was to deliberately privilege the visual and explore visual methods of knowledge production in alignment with the visual communication approaches of the project.

In the workshop, it was also key to surface the voices of young people in relation to cultural activism, as “Student activism and research indicate that the capacities of children and young people remain poorly recognised and under-utilised in visioning climate change education and a better future” (Catanzaro & Collin, 2020). By creating a space to hear and empower youth voices, we honoured the self determination of First Nations young people to connect with and share stories about their individualised connection to Country and place, and supported the commitment of allies in learning more about that connection.

Another essential component of this workshop was thinking about how these shared knowledges and learnings could be used to impact climate change education in the future. To enable this, a combination of practitioner and attendee reflection was enacted to uncover a themed suite of key learnings and recommendations from the mutual processes of workshop planning, facilitation, and participation. This reflective process aligned with the spirit of undertaking authentic cultural engagement as a careful, unhurried activity, and allowed us to investigate what the processes and experiences of participation in the workshop might mean for student and facilitator learning, additional workshop versions, and future pedagogical applications.

With these goals in mind, a cycle of critical reflection was embedded in the project design to allow time to evaluate the workshop and consider the processes and practices emerging from the workshop. A key focus in undertaking this reflective analysis of the workshop was to reflect on the experiences and results of the delivery for future engagement, as well as to assess the value of the combined methods and approaches in effectively facilitating expression and knowledge transfer.

Case Study Objectives

It was determined that a case study developed from the results of workshop would be an appropriate way to collect the insights offered by the multiple processes, practitioners, and participants involved. The goal in communicating that experience through this case study is to generate a working methodology and recommendations and strategies for fostering and developing culturally safe and enriching practices for creative educational contexts.

The intention of the case study is also to reflect upon how creative processes can support the creation of visual outcomes that explore Climate Custodianship informed by First Nations perspectives. The case study also disrupts prevalent narratives of youth as ‘receivers’ of information on climate change (Catanzaro and Collin, 2023). Bringing together Indigenous voices, allied voices, and youth voices, it identifies potential educational benefits of engagement in the overlapping dynamics between youth perspectives, Aboriginal activism and allyship, and climate change protest. More broadly, it examines how Australian youth participants in the global climate movement can be supported to creatively enact and activate these visual approaches to communicating their concerns, fears, attitudes and opinions on climate change through the lens of shared Aboriginal knowledge.

Workshop Design

Methodologically, the workshop took a blended, mixed-methods approach, drawing on Indigenous, visual, and participatory methodologies. Led by an Australian First Nations artist and academic in collaboration with academic practitioners with expertise in visual communication design, participatory making and visual storytelling, the workshops were able to employ multidisciplinary expertise and methodological grounding. This approach included participation and oversight from respected invited Elders, and the inclusion of an arts-based industry host and partner.

As an underpinning principle, the workshop design was guided by Indigenous methodologies, and Indigenous-led approaches to knowledge (Coombes & Ryder, 2020). By deliberately privileging First Nations perspectives (Rigney, 2017) the workshop was grounded in Indigenous ways of knowing, doing, and being, and a commitment to creating a safe space for participants to access place-based, Indigenous knowledge. These Indigenous research methodologies were implemented to enable knowledge to be co-created and shared by participants in culturally appropriate and inclusive ways (Dudgeon, Bray, et al., 2020).

Following cultural and personal introductions and yarning sessions, participants were encouraged to share their stories about the individual and collective impacts of the climate crisis undertaken as part of creative poster-making activity in an Indigenous-led workshop environment. Participants were asked to explore their own connections, positioning and affective relationship to Country and cultural activism and undertake an exploratory process to visualise this using a variety of traditional and contemporary materials that were briefly demonstrated for them. Individuals were able to pick and choose what they wanted to work with, and experiment with process. The combination of old and new technologies created a captivating visual metaphor that represents the traditional ways of connecting to Country, blended with contemporary methods of cultural activism (Carlson & Frazer, 2018).

By providing open-ended and participatory approaches, facilitators created opportunities for the collection of meaningful quantitative data and ultimately created enriching conversations about valuable place-based experiences, where participants are positioned within the context explored (Geia, et al 2013). Activities within these participatory workshops allowed for confidence and skills to be developed, as well as rich data to be gathered by guiding participants through how to communicate messages regarding the climate crisis through processes of visual yarning and supported expression. This builds capacity and provides opportunities for participants to share their stories and experiences, and to reflect on their individual message through participatory making and yarning (Ryder, et al 2020). As an approach, yarning allowed us to overcome some of the limitations of dominant colonial-settler didactic practice (Smallwood, 2023), and facilitate dialogical narratives with participants that prioritised First Nations knowledges and practice in place.

Elements of Workshop Delivery

In concert with the specifically combined suite of interdisciplinary methodological approaches outlined (Figure 1), the workshop was designed to be delivered using a combination of the below philosophical, theoretical, and practical components and activities:

-

- Indigenous-led perspectives

- Traditional place-based knowledge

- First Nations artist leadership

- On Country preparation and materials sourcing

- Yarning circle and introductions

- Invited Elders guidance and participation

- Visual Communication approaches

- Creative Prompts: political context, environmental context, First Nations context, protest, activism, posters, visual communication, words and messages, images and symbols, materials and techniques

- Traditional materials demonstration

- Contemporary materials demonstration

- Making and doing

- Experimentation

- Reflection and observation

- Documentation

The Workshop Process

As identified, placards and posters are a key form of visual communication utilised by young people within the climate movement. By adopting and adapting a poster making approach, we formalised this method into a creative workshop format. To introduce the climate action poster context in the workshop we presented a selection of the visual signage currently featured at the Australian School strikes through photographs captured in the study, Collins et. al New Possibilities: Student Climate Action and Democratic Renewal (2023) and on the School Strike for Climate formal online galleries.

We welcomed open discussion around the way that climate change has impacted upon people in the room, facilitating yarning around key issues that were concerned with specific places and people. Following this, we began connecting individual ideas of what this might look and feel like through relational cycles of visual yarning (Figure 2) that specifically encouraged shared knowledge and storytelling to be created, translated, and developed through visual methods into new visual outcomes. Yarning is a method that can illuminate how different cultures interpret, construe, realise and order knowledge. Accordingly, it is a valuable research method that allows for different cultural epistemologies (Costello & Cameron, 2022) and also creates culturally safe contexts through which participants can share experiences (see for example Coombes & Ryder, 2019; Priest et al., 2017). We believe that this was only further enhanced when specifically combined with visual practice, and suggest that it offered a positive learning experience in the workshop for participants.

Beginning with traditional yarning, these relational conversations, exchanges of knowledge, and storytelling evolve to include sketching, prototyping and patterning as forms of visual knowledge. Following this, key words, messages, or symbols are added to the designs to communicate more clearly aspects of the embodied learning and knowledge sharing that occurred in the workshop.

As the below example demonstrates, the resulting visual outcomes (4) were often layered with a variety of mediums and visuals that refer back to the processes. In this specific example, Indigenous understandings of Country and personhood (Pelizzon, et al., 2021) are referred to through suggesting that ‘Country is Speaking’, expressing perspectives shared in earlier yarning discussions. We also see visual metaphor at work as the layers of old (ochre) and new (acrylic) mediums connect with the storytelling, symbols, experiences, perspectives, and messages that are woven into the visual outcome.

Each individual’s visual outcome communicated a different message, drawing on a number of visual devices – from a burning cockatoo (with no text), to a direct provocation to Community to ‘get up’ as ‘they won’t’, to statements that indicated the kind of future they wanted to be a part of stating ‘I want to grow old with the trees’. Across each visual outcome, we saw the visual yarning process being enacted to support and develop the final outcomes and messages.

Workshop Summary

By involving Indigenous educators and Elders directly in communication and education about understanding climate activism as Custodianship of Country, this project ensured that the knowledge being shared was culturally appropriate, and that the communication was delivered in a way that is respectful, meaningful and relevant to Indigenous communities and allies.

The inclusion of participatory approaches and the incorporation of experiential learning processes reflect their significant ongoing roles in traditional cultural education. Providing opportunities for young people to engage in hands-on activities that connect them materially with the land and the environment through activities such as ochre grinding is a culturally sustaining way of learning inside and outside the classroom.

A focus on the interconnectedness of land, people, and culture emphasised the holistic approach of Indigenous knowledges, which see land, people, and culture as interdependent. This approach aligns with the principles of sustainability and provided a basis in the workshop for understanding how climate activism can be seen as an act of Custodianship of Country.

Elders and educators sharing the importance of community and collective action in Indigenous cultures, and framing this as a correlating aspect of youth climate activism resonated with the workshop participants. This perspective encouraged and empowered young people to work together to identify and achieve common goals and to learn and draw on the knowledge and expertise of Elders and community members.

This workshop benefitted from the inclusion of participants from both First Nations Peoples and different cultural backgrounds. It is argued that Indigenous-led narratives about Country will enrich non-Indigenous participants’ understanding, and more deeply engage them in learning about valuable First Nations approaches to Custodianship of Country.

Visual Storytelling approaches were specifically used as ways of communicating Indigenous knowledge and perspectives. These approaches were used to share stories and experiences of climate concern. Yarning allows room for individual and collective perceptions, reciprocal exchanges, breaking down the perceived hierarchies, and for participants to become comfortable to speak, or listen without speaking, giving everyone the opportunity to become comfortable introducing themselves and their perspectives. This exchange back and forth between yarning and making created a shared visual yarning space where the liminal spaces that existed between listening and making or speaking and making became enmeshed. This observed reciprocal process meant that the resulting visual posters became embodied outcomes of individual and shared ideas and representations.

Analysis

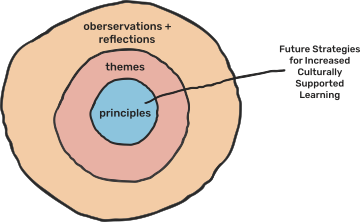

The open-ended yarning and discussion data, observational field note data, generated visual outcomes, and reflective researcher observations were all examined through discursive, analytical and visual methods (see mindmap Figure 4) to identify keywords, themes, and patterns, as well as to contextualise and develop an integrated understanding of what has been discovered through the research (Bazeley, 2013).

The key reflections and observations emerging from these multiple data sets were identified, coded, and refined through multiple stages by the case study team acknowledging the value of reflexivity, subjectivity, and creativity in knowledge production (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2019). After the stages of reflection, examination, codification, and thematic analysis – keywords were distilled and collated under thematic headings, until eventually, an alignment with the vital Indigenous framework of Knowing, Being, and Doing (Martin, 2003) was recognised. Inspired by Martin, and in alignment with significant Indigenous research and practice already incorporating these concepts, they also became the titles of the three broad principles framing our communication of the case study outcomes (see the table in Figure 6).

The principles offer a familiar structure within which to articulate both the facilitators’ and participants’ understandings and experiences of the workshop. Acknowledging that everyone’s ways of knowing, being and doing are interwoven with personal meanings, cultures, values, perspectives, and practices – the framework also reflects the facilitators’ and participants’ sharing and learning across multiple cultural interfaces. Moving beyond the workshop case study, each principle suggests a shift towards even more decolonised approaches and with practical implications for future workshop delivery and strategies for further educational application, and learning grounded in the data, drawing on cultural, practical, and theoretical concepts and evidence from the broader research.

OBSERVATIONS AND REFLECTIONS |

THEMES |

PRINCIPLES |

STRATEGIES |

| indigenous protocols, yarning, circle, elders, knowledge, led with/by knowledge-sharing, elder-guided, responsibility, accountability, sovereignty, locating, placing, establishing, respect, relationality, connection, relationships, responsibility, authenticity, care, cultural, shared, reciprocity, understanding | Respect Relationships Responsibility |

Knowing |

|

| scope, shift, deep listening, responsive, attention, activity, adaptations, time, adjustments, activity estimates, direction changes, organic, present, evolving, Aboriginal temporalities, relational not linear, being present, not ‘watching the clock’, seasonal calendars, not a progression of dates, spontaneity, periodisation, adaptation, unstructured, flow, moment, less control and timetabling, flexible, relaxed, conversational, assumptions, focus, organic, indirect, awareness, attention, emerge, reveal, engaged, situated | Time Responsiveness Attention |

Being |

|

| intuition, practicality, materiality, pragmatism, tactility, exploration, play, experimentation, open, responsive, tacit knowledge, testing, prototyping, processes, assumptions, generation of materials, relatability, use, tools and techniques, alignment, recognition, assets, formal vs. informal, simple, cultural, familiarity, immediacy, appropriateness, thinking through making, honest, raw, cultural, relevance, rewarding, patterns of making, preferred making | Process Materials Actions |

Doing |

|

Figure 6. Table of distilled Observation and Reflection Keywords, Themes, Principles, and Strategies

The Principal of Knowing

Respect/Relationships/Reciprocity/Responsibility

“the learnings assumed to be a focus of the workshop

were not necessarily the learnings revealed by the workshop”

Reflection

As part of the workshop experience, attendees were given opportunities to understand the importance of Indigenous protocols that included acknowledging the Traditional Owners of the land upon which the workshop was convened. Participants respectfully participated in proper introductions with First Australians from Jerrinja and Gadigal Nation areas, they engaged in storytelling practices aligned with preferred Aboriginal approaches to structure and content. With Jerrinja Elders Aunty Grace and Uncle Gerald’s arrival, participants made sure they were comfortable and attended to. At Aunty Grace’s suggestion, everyone was brought into the circle for yarning, and to note the circle’s symbolic value in conceptually representing one community.

Aunty Grace offered all present the opportunity to engage in traditional ways of knowing, this involved all participants creating a large yarning circle in which all were encouraged to offer an introduction. Aunty Grace explained the cultural importance of communally uniting peoples through positioning all within a conjoined yarning circle where no one person was placed in a hierarchy above any other. The process of observing protocol placed people at the centre and kept space for respectful, kind, and generous sharing of knowledge that occurred through the cultural mentoring of a senior Aboriginal Elder.

The formation of this culturally safe yarning opportunity engaged multicultural allied participants in terms of place and identity and was an enriching way through which to discover the participants’ shared goals of climate activism and unite these with Indigenous cultural and spiritual responsibilities of Custodianship of Country.

Whilst we had planned for each individual to connect their own unique cultural heritage to their own ‘places’, the shift towards embracing a more open-ended approach to timing that was directed by participant yarning and not defined by the priority of meeting the previously devised running schedule for the workshop. This supported participants engaging more deeply in exploring and forming meaningful connections with each other, it created a yarning space where Indigenous participants felt safe to share aspects of their cultural histories and knowledges and offer understanding on histories of their Kin and Communities.

Participants observed the importance and strengths of these approaches, and recognized the need to respect protocols, processes, and storytelling as part of establishing Indigenous contexts, connections, and relationships. More connections were made and shared though the workshop yarning process which spanned Country, climate, and connection, as custodianship and responsibility for Country were acknowledged, and explored by the group.

Strategies

On reflection, it is important to embrace the need for collective connection and storytelling. This means not simply jumping into a designated structure or activity, but taking the time to build relationships and establish context.

It’s also important to give proper attention to the different forms of knowledge that exist both inside and outside of formal workshops or educational settings. This means recognizing the value of experiential learning and informal knowledge-sharing, as well as more structured approaches.

In creating a culturally relevant learning space an essential future strategy would be to weave in (even more closely) the identified themes of Country, relationships, reciprocity, and responsibility. This means acknowledging the land and its history, fostering meaningful connections between learners and their communities, and recognizing the importance of reciprocity and accountability in any learning process, but especially in Indigenous contexts.

Finally, it is important to respect protocols, processes, and storytelling as part of establishing contexts, connections, and relationships within an Indigenous learning community. This means recognising and honouring the different ways that knowledge is transmitted and shared, and valuing the role that storytelling plays in shaping our understandings.

The Principle of Being

Time/Responsiveness/Deep Listening/Attention

“Planned timeframes changed, and new timeframes created themselves”

Reflection

During the workshop, it became apparent that any attachment to previously established timeframes was not appropriate, as the balance of time and activity shifted significantly and organically. As a response, the workshop timings were reconsidered reflexively, and the pace of the workshop was actively adjusted.

After Elders and special guests, Aunty Grace, and Uncle Gerald were made welcome and comfortable, the shorter, structured scene-setting and contextualisation planned at the start of the workshop soon made way for a longer, more meaningful series of introductions and the processes of coming to know each other outlined above. This shift in perceptions of time also highlighted the need for new temporal forms of attention and durational perspectives that could help to grasp the depth of the concept of Country, as well as support authentic knowledge-sharing and making people aware of significances, voices, and learnings. Deep listening, or Dadirri (Ungunmerr-Baumann, 2022), was encouraged, and participants responded with great attention to honour the wisdom and knowledge of the Elders in attendance and of Indigenous Peoples.

The importance of not underestimating the capacity for ideas with simple materials was noted, and on reflection, it was suggested that ideas should not be over complicated, but rather allowed to emerge through authentic engagement. To allow for proper attention to be given to each stage of the workshop, speaker, or idea, it was felt that streamlining, reducing, or simplifying the amount of formally presented information, materials, and tools would be of benefit. This would enable a more flexible or shifting focus, allowing awareness to be experienced, and perspectives to resonate.

It was observed that directed, detailed, or explicit knowledge was not always as powerful or important as more indirect experiential movements towards greater understanding or connection and that the informal yarning and visual yarning that occurred whilst making proved to be more effective in encouraging engagement with the shared process of relating, and allowing understandings to emerge. This more culturally appropriate approach to shared learnings and practices allowed information and techniques to be discussed with participants one on one, and in small groups as needed, as they worked through individual stories, visual concepts, possible approaches, and new ideas. On reflection, and for future deliveries, this would be supported through less scheduling and a deliberate open allowance of time to better account for Indigenous protocols and temporalities, and the authentic experiences of the timing of the workshop.

Strategies

To authentically align with Indigenous temporalities, it is necessary to allow for proper attention to be given to proper engagement, the establishment of connection, and anticipating changes in the requirements of each stage of the workshop, speaker, idea, or material. Accommodating this flexibility may involve streamlining, reducing, or simplifying the amount of formally presented information, materials, and tools. Additionally, allowing for more flexibility and shifting focus may create space for awareness to be experienced, perspectives to resonate, and understandings to emerge.

Possible actions drawn from reflections would also be to reconsider workshop timings based on Indigenous perspectives to prioritise Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing throughout the workshop experience. This may include allocating more time for yarning, communication, and storytelling, as well as honouring invited guests, anticipating their needs, and ensuring their comfort. It could also take the form of changes of direction in discussion, creating, material responses, or participant needs. Through these types of adjustments, we could better support the creation of a workshop space that values and accepts more flexible notions of time. This flexibility gifts room for changes and shifts in direction, which align with Indigenous perspectives and support culturally appropriate experiences for participants, as well as respectfully privileging the presence, needs, and preferences of Elders, Indigenous community, and guests.

The Principle of Doing

Processes/Materials/Experimentation/Making

“responses to different materials became apparent,

and patterns of preferred making and experimentation emerged”

Reflection

During the project, the participants responded enthusiastically to grinding and using ochre, while secondary mark-making techniques based on printing or stamping were used less frequently. The more didactic processes of teaching/learning printing processes were not revealed to be as appealing as a tactile and immediate connection with materials and making for participants.

Materially, multiple types of ochre were sourced on Country locally and ground to share as part of the workshop framing and as colour examples and samples to paint with. Importantly, solid pieces of ochre and a selection of grinding stones were also offered in the early making and stages of the workshop. Participants engaged dynamically with the grinding process as an activity connected explicitly to the discussions of Country and the knowledge-sharing from the start of the workshop. Connecting to Country through linking materials, processes, actions, and outcomes to Indigenous knowledge and the local area is a positive recommendation for future workshop iterations. This not only connected participants to Country, but it also reinforced the relationship that the ‘call to climate action’ has with the earth and world around us.

Many participants found it natural to move from painting with ochre to painting in a combination of ochre and acrylic, and this technique resonated very well. Another learning opportunity was revealed after the workshop, as poster outcomes which had not had binder included with the ochre began to flake. The need to bind ground pigments is a technical practicality that spans traditional and contemporary, as well as First Nations and Western creative practice. It was felt that in future, place-based Indigenous knowledge of specific binding materials could be incorporated for this type of activity.

Text creation was also an important component of the poster messaging process, and multiple tools and techniques were offered and demonstrated to participants. This was with the understanding that participants were not necessarily art or design trained, and with the intention of assisting in making the text-creation process easier. However, the more immediate and experimental techniques of text creation – such as using paint over removable ‘painters’ tape (see Figure 3) to create type – proved more popular and appealing to participants than the text creation processes that involved pre-fabricated tools, or prescribed lettering shapes and processes. This DIY approach and aesthetic demonstrated knowledge of the visual language of contemporary climate protest, where visual lettering is often imperfect but bold and impactful.

Play and experimentation were also revealed as key actions and approaches. The participants who used the painters’ tape technique seemed to be more open to chance in their poster-making process and were willing to experiment with different message-making options – excited as the tape was removed and the visual text was revealed. Tape and paint emerged as a familiar, tactile, easily modifiable, and approachable medium for incorporating text, creating a sense of immediacy, and even urgency among the participants.

Strategies

Critical reflection reinforced that when facilitating practical workshops, pragmatic actions and adjustments are necessary to ensure a successful outcome. Basic considerations such as allowing for additional time for drying work to layer successfully should be taken into account. This is particularly relevant when using materials such as ochre, which may require extra time to bind and layer properly. Based on learnings from previous workshops, it may be beneficial to make even more ochre available to participants, possibly ground in advance or grinding in situ, and use it as underneath layers and patterns underneath the painters’ tape masking technique.

More nuanced considerations would be to allow for both simplicity and complexity, processes of patternmaking and layering, thinking-through-doing and time for consideration of words and messaging while making connections through materials. More time for thought, experimentation and exploration would encourage play and more crucially help resist the pressure to focus solely on outcomes, but instead, focus on the process.

It is also essential to look for primary connections with materials and not assume what participants might respond to. Streamlining the use of multiple materials and tools where possible can be helpful, and based on reflective learnings, it is crucial to consider the tactility and appropriateness of processes and materials, making them relatable and immediate to participants. Aligning materials and processes closely with the cultural knowledge expressed can be beneficial, and authentically connecting to Country is a priority.

Future Applications

The workshop model reflected on in this case study allowed youthful advocates to express collective care and responsibility for Country, embedding respect for Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing, and exploring the difference in focus and pace of a First Nations led creative workshop process. By documenting and critically reflecting on lessons learnt from the delivery of the workshop, we were able to consider our teaching practices in light of the decolonising, knowledge-sharing, educational, climate action, youth empowerment, and creative goals of the workshop, and reveal useful future strategies to take forward for culturally supported learning.

Figure 7 illustrates how the Indigenous principles of knowing, being and doing can be embedded within workshop design in a practical capacity. The intention is that each element or recommendation can be applied to new or existing teaching and learning deliveries in multiple fields – as an additional layer of consideration to adapt the delivery of an existing workshop, or used to to support the development of new workshop and creative teaching approaches.

In combining Indigenous perspectives with climate education, we can see there is increased understanding of the significant role climate change education has in promoting students’ understanding, attitudes, and actions towards climate change, yet there is concern that the current methods and strategies used in teaching climate change are insufficient (Cutter-Mackenzie & Rousell, 2019; Rousell & Cutter-MacKenzie-Knowles, 2020 discuss). The representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in teaching and learning is even more insufficient, but First Nations cultural perspectives are essential in educational and civic approaches for healthy climate futures. We believe this workshop model prioritises the Indigenous lens as an alternative and essential means to understanding and shaping responsive climate education and improving public understanding of youth protest and action.

Key understandings from this workshop also reinforce that when young people are invited into the conversation about their futures, their responses and engagements are deeply considered, insightful, and intelligent, and in the case of this workshop outcome, their generated visuals are impactful and powerful. Young people’s voices on climate change are continually silenced or ‘problematized’ and this workshop model is committed to amplifying youth voices as well as those of First Nations people and allies in the call for climate action. We agree with the work of Bessant et al (2023) that calls for a move beyond the ‘adultist’ and ‘rigid, top-down understandings’ (Bowman 2019) of young people’s political participation (Collin, 2015; Wall, 202, cited in Bessant et. al 2023). We believe this lack of visibility can be addressed by drawing on Indigenous-led approaches to understanding climate and Country and by empowering Indigenous youth and their allies beyond generalised assumptions of their capabilities and the types of deficit thinking discourses still often applied to younger generations and First Nations peoples.

This model is not just for Indigenous students, but cultural allies, and students new to Indigenous studies. The workshop model can be adapted to be intergenerational so that the messages shared by young people can be understood by their Communities and Kin and/or used to spark yarning sessions with those in power or those who have power to enact change. Additionally, the visual nature of the workshop outcomes allows for extended audiences and responsiveness – demonstrating creative, adaptive and resilient thinking in connection to climate action.

Many insights that were identified through this process emerged as a consequence of the Indigenous-led focus of the workshops. Despite a number of the delivery team being Indigenous themselves and/or experienced in Indigenous education, some facilitators noted that it still took considerable attention to step away from the (often) dominant European teaching practices familiar within Western educational settings. Multiple elements of these efforts are captured in the proposed future strategies, and are important individual and collective considerations to support critical decolonising actions that privilege Indigenous methodologies in education settings inside and outside the curriculum.

Another experiential insight from the workshop was the deep connection to place that was achieved through being on Country and using ochre from the land in which the workshop was held. This also honoured traditional forms of connection and learning in Indigenous culture. It was noted that the project could be extended further to include additional multidisciplinary and First Nations perspectives, particularly in terms of language inclusion, and we believe that the combination of ochre work, and incorporating place-based language words reflecting Country could help frame and localise the workshop processes even more effectively in the future.

In framing the workshops, and as a concurrent reflection and research activity, we were able to summate and communicate the importance of featuring First Nations perspectives in climate educational and climate action approaches. Through foregrounding Indigenous perspectives in a First Nations artist-led workshop process, students were encouraged and supported to visualise their own expressions of climate justice.

The project aspired to facilitate youth stakeholders to consider, share, reflect, and create visual statements of climate concern centred on understandings of First Nations perspectives of responsibility and care for Country. Breaking down the Western dichotomies between sciences and humanities that do not exist in a more holistic Indigenous knowledge systems which encompasses multiple types of knowledge.

Our aim is that in doing this, we have developed a suite of methods to facilitate knowledge transfer and responsive creative expression more effectively in Indigenous-led climate change educational scenarios making room for deepening respect and culturally supported creativity. We aim to have made suggestions beyond learning materials and visual strategies, but more importantly how First Nations perspectives and insights into the possibilities of real change, what drives and sustains it, and how our efforts as humans can bring about change (Tuhiwai Smith et al., 2019). We hope to have highlighted the transformative benefits of centering culture in generating authentic, student-centred learning opportunities and artefacts that make knowledge visible.

Conclusion

“You are sitting in this room, because, I believe, you are chosen to be the next messengers,

the new carriers, particularly for what we want, with land and sea and our beliefs

and our values, because that is what is missing”.

– Aunty Grace

Communicating youth climate activism as Custodianship of Country through an Indigenous educational lens requires a culturally appropriate and respectful approach that recognizes the diverse cultural knowledge and perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

This project represents a meeting of stories and a shared climate call to arms informed by an understanding of Custodianship of Country. Visualising and documenting these stories through youth-led understandings enriches our cultural knowledge by prioritising and celebrating overlapping cultural values relevant to place-based specificity.

By incorporating Indigenous knowledge and philosophy into visual communication design, we can create powerful messages that raise awareness about the importance of caring for the environment and inspire action to address climate change. These messages can be targeted towards youth audiences and can help to create a more sustainable and inclusive future for all.

Through processes of learning from Aboriginal perspectives on climate and the environment, youth allies can gain a deeper understanding of the importance of caring for the environment, the benefits of collective action, the value of cultural knowledge, and the need to build resilience in the face of environmental change. This knowledge can inform more sustainable and inclusive approaches to education and climate activism that are rooted in Indigenous knowledge and perspectives.

Some Useful Definitions of Terms

Country

In First Peoples’ contexts in Australia, the use of the word ‘Country’ (capital C) is a concept that refers to much more than western understandings of physical land. Country extends to skies and waters; it is family and a place of origin, culture, belonging and belief.

Dadirri

A term used by the Ngan’gikurunggurr and Ngen’giwumirri peoples of the Northern Territory of Australia, ‘Dadirri’ refers to a deep listening and contemplative practice that is used to connect with the natural world and one’s own inner self.

Ochre

For Indigenous people Ochre is a precious cultural resource connecting them to Country. Primarily natural pigments and minerals, it is mixed with fixatives so that the pigment can be painted on rock, objects, and skin, for purposes including ceremony, medicine, and storytelling.

Yarning

In Australian Indigenous contexts, ‘yarning’ is a culturally specific form of conversation and knowledge sharing. It is a way of communicating that emphasises relationships, connection, and listening, and which may incorporate storytelling.

Visual Yarning

A process of visual knowledge translation and generation that embodies place, identity and storytelling. It is a relational method that deliberately privileges visual aspects of communication, connectedness, and collaboration for the development of new visual knowledge.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge First Nations Peoples, Elders, and Ancestral Spirits of Australia. Without the Custodianship of Traditional Owners of the Nations upon which this research work was conducted, we would not have the benefit of connecting to Country and engaging in knowing, doing and being as Ancestors have continuously done for tens of thousands of years.

We would also like to thank the First Nations students and cultural allies that participated in the workshop, and Aunty Grace and Uncle Gerald who have contributed to this research by sharing their knowledge and stories.

This research was funded by Western Sydney Creative and supported by UTP Arts organisation. We acknowledge our co-researchers in the project (listed below) and thank them for the broader contribution to the intellectual work of the project which informed this project.

Madison Shakespeare

(First Nations Lead, Artist, and Creative Producer)

Dr. Caelli Jo Brooker

(Artist/Designer and Co-facilitator, The Wollotuka Institute at The University of Newcastle)

Dr. Michelle Catanzaro

(Project Lead and Co-facilitator, Western Sydney University)

Dr. Jessica Olivieri

(Industry Lead and Co-Facilitator) Artistic Director/CEO UTP

Dr. Rachel Morley

(Associate Dean of Engagement and Co-facilitator, Western Sydney University)

Dr. Katrina Sandbach

(Designer and Co-facilitator, Western Sydney University)

References

Bazeley P. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: Practical strategies. SAGE.

Bessant, J., Mesinas, A. M., & Pickard, S. (Eds.). (2021). When students protest: Secondary and high schools. Rowman & Littlefield.

Bessant, J. (2021). Making-up people: Youth, truth and politics. Routledge.

Bessant, J. Collin, P. Watts, R. Ayres, A. (forthcoming 2023) ‘Blah, Blah, Blah …[not] business as usual’: Politics Through the Lens of Young Female Climate Leaders’

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health, 11(4), 589-597.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Bowman, B. 2019. Imagining Future Worlds Alongside Young Climate Activists: A New Framework for Research. Fennia 197 (2): 295–305.

Carlson, B., & Frazer, R. (2018). Yarning circles and social media activism. Media International Australia, 169(1), 43-53.

Catanzaro, M., & Collin, P. (2023). Kids communicating climate change: learning from the visual language of the SchoolStrike4Climate protests. Educational Review, 75(1), 9-32.

Collin, P. (2015). Young citizens and political participation in a digital society: Addressing the democratic disconnect. Springer.

Collin, P., Churchill, B., Gordon, F., Bessant, J., Catanzaro, M., Watts, R., Jackson, S. (2022) ‘Disappointment and disbelief’ after Morrison government vetoes research into student climate activism’ The Conversation Published: January 13, 2022

Coombes, J., & Ryder, C. (2020). Walking together to create harmony in research: A Murri woman’s approach to indigenous research methodology. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 15(1), 58-67.

Costello, O., & Cameron, L. (2022). Yarning up with Oliver Costello–An interview about Indigenous biocultural knowledges. Ecological Management & Restoration, 23, 22-25.

Cutter-Mackenzie, A., & Rousell, D. (2019). Education for what? Shaping the field of climate change education with children and young people as co-researchers. Children’s Geographies, 17(1), 90-104.

Dudgeon, P., Bray, A., Smallwood, G., Walker, R., & Dalton, T. (2020). Wellbeing and healing through connection and culture. Lifeline Australia: Sydney, Australia.

Finley, S., Messinger, T. D., & Mazur, Z. A. (2020). Arts-based research. SAGE Publications Limited.

Geia, L. K., Hayes, B., & Usher, K. (2013). Yarning/Aboriginal storytelling: Towards an understanding of an Indigenous perspective and its implications for research practice. Contemporary nurse, 46(1), 13-17.

Martin, Karen L. & Mirraboopa, Booran (2003) Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for indigenous and indigenist re‐search. Journal of Australian Studies, 27(76), pp. 203-214

Muxel, A. (2010). Avoir 20 Ans en Politique. Les Enfants du Désenchantement. Paris.

Pelizzon, A., Poelina, A., Akhtar-Khavari, A., Clark, C., Laborde, S., Macpherson, E., … & Page, J. (2021). Yoongoorrookoo: The emergence of ancestral personhood. Griffith Law Review, 30(3), 505-529.

Rigney, L. I. (2017). Indigenist research and aboriginal Australia. In Indigenous peoples’ wisdom and power (pp. 32-48). Routledge.

Rousell, D., & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A. (2020). A systematic review of climate change education: Giving children and young people a ‘voice’ and a ‘hand in redressing climate change. Children’s Geographies, 18(2), 191-208.

Ryder, C., Mackean, T., Coombs, J., Williams, H., Hunter, K., Holland, A. J., & Ivers, R. Q. (2020). Indigenous research methodology–weaving a research interface. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 23(3), 255-267.

Shakespeare, M., Catanzaro, M. Brooker, C.J. (forthcoming 2023) Climate Justice: Visual expressions of Australian Aboriginal perspectives, Handbook of Grassroots Climate Activism, Routledge.

Smallwood, R. (2023). Expressions of identity by Aboriginal young peoples’ stories about historical trauma and colonisation within the Gamilaroi Nation. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 11771801221146777.

Smith, L. T., Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (Eds.). (2019). Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Wall, J., 2021, Ethics in Light of Childhood, Georgetown university Press, Washington.

Ungunmerr-Baumann, M. R., Groom, R. A., Schuberg, E. L., Atkinson, J., Atkinson, C., Wallace, R., & Morris, G. (2022). Dadirri: an Indigenous place-based research methodology. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 18(1), 94-103.