Terrellyn Fearn (Lnu'sqw/ Irish)

Connection is the Correction

Terrellyn Fearn (Lnu’sqw/ Irish)

Overview

Terrellyn discusses relearning/unlearning Indigenous language and epistemologies of the sacred feminine. She shares the concept of Metuaptmumk, where breath is mingled, tensions are held, and the spirit realm is accessed. For Terrellyn, innovation is not thinking outside the box; rather, it is thinking inside the circle, around the fire, inside the lodge.

This interview was originally released on February 6, 2023, and has been edited for clarity.

The Interview

Gladys Rowe: Tansi, greetings. Welcome to Indigenous Insights. I’m your host, Gladys Rowe, and I’m so grateful you are here. My guest for the second episode in a row is Terrellyn Fearn. Terrellyn is the Project Director of Turtle Island Institute for Indigenous Science, a global Indigenous social innovation, a teaching lodge enabling transformative change. She brings understanding of Indigenous wellbeing and community building through rematriation and Indigenous ways of knowing. For 30 years Terrellyn’s work has focused on advancing social justice and systems change in health, gender-based violence, education, and child welfare in over 400 Indigenous communities throughout Turtle Island. In 2017 she was the Director of Outreach and Support Services for the Canadian National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, supporting family members and survivors of violence. She is a Master of Education candidate at York University and a Research Associate at the Waterloo Institute for Social Innovation and Resilience, where her studies focus on complexity theory, ethical space of engagement, Indigenous feminism, and healing-centred design. She also contributes to decolonization of the Canadian criminal justice system through her work on the Indigenous advisory circle for the office of the Federal Ombudsman for victims of crime.

Welcome back, Terrellyn. We left off last time when I felt like we could have talked for days. I’m wondering if you’d like to share a reintroduction.

Terrellyn Fearn: Weli eksitpu’k, greetings, Gladys. Nice to see you again. I’m happy to be here and sitting with you. I’m L’nu, or Mi’kmaq, Snake Clan of the Wabanaki Confederacy.

When we introduce ourselves, I always think: How do we bring our ancestors with us into these spaces? How do we carry them into our conversations? My paternal grandmother told me the story of my name. She was the youngest child and she tagged along behind older siblings who followed the Barnum & Bailey circus, and she was really mesmerized with the lion tamer and the lion tamer tent. From dawn till dusk, my relatives, her brothers and sisters, could find her there. There was something about this lion tamer managing all these lions. That lion tamer’s name was Terrell Jacobs, and so my father was named after this famous lion tamer. I am my grandmother’s firstborn grandchild and my father’s first born. So I received that name Terrell, with a -yn ending. So my English name has foretold some of my life’s journey to get to this point, where I feel I’ve been managing lions in the many systems that I’ve ventured to disrupt and to change and understand.

My Mi’kmaw name, my spirit name, is Milita’j, meaning hummingbird, and that name was awakened for me over a seven-year process with the Midewiwin Lodge and gifted by Elder Jim Dumont, a faith keeper in the eastern doorway of the Midewiwin Lodge. Milita’j has many stories indicating my responsibilities and my gifts and my ability to move in multi-directional ways. As a hummingbird, I also have the ability to stand in the physical realm and pierce my long beak through the spiritual realm to reclaim information and knowledge and wisdom from the spiritual realm, from our ancestors. I’m currently joining you today where my two feet are planted on the beautiful lands that have been stewarded by the Anishinaabe and the Haudenosaunee peoples, where I’ve been living in relationship with these lands for about 18 years, just north of Toronto, Ontario. Thanks for inviting me back.

Gladys: You are welcome, the pleasure’s all mine. Thank you for sharing all those pieces of yourself and entering the space in that whole way.

In my experience Indigenous health research has embraced this idea of two-eyed seeing since the mid-2000s. I know this is something that you’ve been thinking about taking further. So here’s an invitation to jump into talking about two-eyed seeing and what that means for learning, evaluation, inquiry.

Terrellyn: Yes, and maybe I’ll start with a bit more about who I am. I want to honour my Irish maternal grandmother, the late Marion Doody. Her family came over in the mid-1800s from Sligo and Cork Counties in Ireland and settled in Mi’kma’ki, Nova Scotia, the homelands of my paternal grandmother’s people. My Irish ancestry ties into two-eyed seeing. The late Tuscarora Elder Rose Imai used to say that Indigenous people with mixed lineages were fortunate because we could live and sense-make within two knowledge systems. I feel that in my own life. My Mi’kmaq lineage grounds me, and my Irish lineage helps me understand Western systems. That bi-cognitive way of moving shaped the inquiry I carried out around the Sacred Fire of Peace for thirteen moons. It was about cultivating a deeper understanding of who I am and what I might contribute to the transformative changes needed in these times.

When I finished with the National Inquiry, I began spending more time with one of my Elders, Miigam’agan, a Mi’kmaq, Wabanaki woman and a Grandmother. Sometimes she feels like a big sister, sometimes she reminds me of my grandmother, but always she is a trusted Elder. She is also part of the circle of Elders and knowledge carriers guiding the Turtle Island Institute for Indigenous Science. She told me that if we truly want to understand who we are as L’nu women, as Mi’kmaq women, as Wabanaki women of the dawn, we must learn our language. Everything is encoded there: who we are, how we are, where we come from, and all the sacred gifts we carry.

So I began the journey of deepening into my language. During COVID, many language programs became accessible online, so I joined a few. One sent me flashcards in the mail. When the first Zoom class began, the Elders opened with prayer and asked everyone to stand, bless themselves, and recite the Lord’s Prayer. It felt to me like a virtual residential school. The teaching method – flashcards, repetition – was a Western way of learning. That wasn’t what I was searching for. I wanted to understand the living spirit of our language. I tried another course, but again, it didn’t feel right. Finally, I reached out to my Elders and said, I want to learn, but this is my experience. They responded, We’ll teach you. For the past three years, I’ve met weekly with Miigam’agan, learning language in a deeper way.

Around that time, one of our speakers was sharing a “word of the day” on Facebook. One day, he posted skite’kmujewawti. I thought I knew it. My father had taught me it meant the way of the devil, and I was proud I recognized it. But the Elder explained: skite’kmujewawti is actually the Milky Way – the Ancestors’ Road. It’s the pathway our spirits travel we pass, the road we all came down from the spirit world to this realm.

I was stunned. The word my father had passed down carried a completely different meaning in its true sense. That was the first time I felt the full weight of colonization and genocide inside our Mi’kmaq language – what Miigam’agan calls The Great Disruption. It shook me to realize, if such a sacred part of our creation story was changed, then what else has been erased?

That question carried me deeper. I began to study the feminine and spiritually-rooted aspects of our creation stories. In Mi’kma’ki, contact began in the late 14th century. Missionaries learned our language, then reshaped it – embedding a Christian worldview, extracting the feminine, altering symbols and stories of who we are as L’nu. That distortion still echoes today. If language is our pathway to understanding who we are and how we are in relation to all creation, and the feminine essence has been erased, then what is my responsibility to reclaim it?

This became part of my 13-moon journey around the Sacred Fire: restoring language as a way of restoring the sacred feminine. As Miigam’agan teaches, “We must unwind the colonization within us, unravel it, and rebuild connection.” That was the work I carried into the fire – rebuilding my connection as a L’nu woman, asking: What does the sacred feminine mean? How do we restore it through language?

Invitation to Thought

Learning language can be more than memorizing words; it can restore ways of being and deepen connection.

- What are your experiences of learning language?

- Why is community so key to learning language?

- Has learning a language ever introduced a new perspective or restored one you’d lost?

Through this process, Miigam’agan shared many teachings. Mi’kmaq is her first language, English her second. She works closely with Clan Mothers and Grandmothers who have spent decades – 30, 40, 50, even 60 years – bringing the sacred feminine back into our language, governance, and family systems. Their work is about rematriation – restoring the feminine to its rightful place in our way of life.

For me, this was a path of turning myself inside out, Indigenizing my consciousness. It raised questions: What does this mean for my identity as a 49-year-old woman? What does it mean for young people – for my nieces, nephews, friends’ children, community? What does it mean for young women trying to claim power, place, and self-understanding?

“We must return to the language.”

– TerrellynThe answer kept coming back: We must return to the language. Focusing on rematriating the feminine in the language created a pathway for this work – a pathway toward true transformative change.

Gladys: So much that is arresting in your opening! Before we explore that pathway as you share your stories and the wisdom that you’ve gathered through this reclamation process, I want to ask a question that may come from my lack of understanding. When you think about the work of restoring the sacred feminine, how does that connect to or understand our community members who identify as Two-Spirit or gender diverse? How does that reclamation connect with who they are?

Terrellyn: Oh, this is such a great and important question, and it’s incredibly relevant today. One of my Elders always says, Connection is the correction. And when I think about the impacts of colonization and the internalized oppression that so many of us carry – not only Indigenous people, but also our Black brothers and sisters, and our Two-Spirit relatives – one of the effects is this siloing. We get boxed into categories like good or bad, this or that, and this othering continues in the spaces we occupy.

I reflect on gender, I don’t identify as Two-Spirit; I identify as L’nu, which means the original people – a term that connects us to the originators of this land, the keepers of this place. In our language, the word e’pit is often translated as woman, but if you break down the word and its relationship to other words, it means carrier of the eggs, the vessel through which life comes. That understanding is crucial.

When I think about the sacred feminine, I think about the different intelligences we all carry: physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual. The feminine intelligences are the heart medicine, our emotions, our spiritual essence. The masculine intelligences tend to align with the mind, the decision-making, the action-oriented parts of ourselves. And as two-legged beings, we all carry both energies – both intelligences – inside us.

I remember my Wabanaki sister Sherri Mitchell sharing something beautiful about Two-Spiritedness. She likened it to the sacred space between masculine and feminine – the pipe. The bowl of the pipe represents the feminine, the stem represents the masculine, and the spirit of the pipe isn’t activated until both come together. You must draw the air from the feminine bowl before you can inhale and send prayers to the Creator.

Our bodies work in a similar way. We often think the brain alone is the decision-maker, the seat of mental intelligence – what we might call “male energy.” But the heart has around 40,000 neurons that communicate with the brain. The heart sends messages, informs the mind, guides decisions, and then the body enacts them. The feminine informs the masculine – they work together.

So, when I think of the sacred feminine, I think of this spiritual and emotional intelligence – the heart-centered wisdom – that patriarchal society has not valued or allowed to thrive. And that’s where Two-Spiritedness comes in: the balance of masculine and feminine energies. One Elder shared with me that those born through their mother’s vessel as Two-Spirit come fully balanced. They have this remarkable ability to move in harmony with both energies. They are sacred beings brought into the world to help restore balance.

Much of my earlier work was in family systems, and an Elder once shared something powerful: many of our Two-Spirit relatives are coming forward in these times because they are caregivers of our children. In a world where we’ve lost ways to care for our children, they are here to guide, nurture, and heal. They are medicine people.

We cannot talk about restoring the sacred feminine without acknowledging our Two-Spirit and gender-diverse relatives. They are central to this work. So thank you for bringing attention to this and inviting them into this space and dialogue.

Gladys: Thank you for sharing those connections and going deeper to build that foundation of understanding. Something that stood out for me is “Connection is the correction.” That’s such a lovely phrase.

Terrellyn: Yeah, it was Jane Middelton-Moz, an Anishinaabe Elder, who shared that with me. She’s done a lot of work with ACOA in the U.S. – the Adult Children of Alcoholics – and has done extensive reconciliation and healing work in our communities. When I was living in Lkwungen territory, she hosted a local workshop. I remember sitting in a circle – I was 27 at the time, still quite young – and she guided us through a family systems exercise.

We all sat in a circle, and she invited participants to step into the centre and enact roles. She set up a family system with an alcoholic parent, and then brought in the children, guiding everyone through the interactions. Watching it unfold, I had this moment of clarity: I could see myself in the family, I could see my siblings, I could see my parents. It was deeply impactful and sparked my own healing journey. I realized I could take my parents off the pedestal I had put them on. I could see that they had stories of how they came to be my parents. I decided I was going to have those difficult conversations with them – not to judge or blame – but to better understand how I could carry forward the beautiful teachings they had shared with me, while also working through the internalized colonization and oppression that had echoed through my family.

“Everything I do is grounded in relationality and care – rebuilding and bridging connections, to who we are, to our families, to our communities, to our Earth Mother, and to all of creation.”

– Terrellyn

She always said, “Connection is the correction,” and I think about that all the time. Rebuilding relational connections is at the heart of the work I do. Everything I do is grounded in relationality and care – rebuilding and bridging connections, to who we are, to our families, to our communities, to our Earth Mother, and to all of creation.

Gladys: Wonderful. That is a thread that’s come through a few of the conversations I’ve had here, around really knowing who you are and where you come from in order to know where you’re going and what your purpose is. You’re bringing your whole self into this space as someone who is committed to doing this work with communities and who is thinking about how to go deeper. That happens in part through your understanding that language holds so much of the knowledge about how we rebuild that connection, how we rematriate. So I’m wondering if you could walk us through the thinking you’ve been doing around this idea of rematriation and the sacred feminine, and how it relates to the work that we need to do in knowledge gathering, in inquiry, and how it might thread into the work of evaluation and innovation too, which I know you’re thinking about.

Terrellyn: Mm-hmm. Yeah, absolutely. I think it’s so important to share our stories and be open and transparent about the work we do – to be accountable.

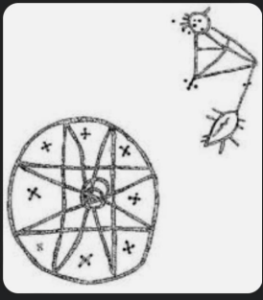

When I was going back to the Sacred Fire for 13 moons and learning our language, my Elder Miigam’agan shared a petroglyph from our territory with me. It’s a petroglyph of the eight-pointed star, and you’ll see versions of that star all over Mi’kma’ki. I asked her about the teachings of the eight-pointed star, and she said, Right next to that petroglyph is a smaller one, but nobody really talks about it. The main star is a depiction of the Pleiades constellation, and the smaller image, what to me looks like a spider on a web, represents the feminine entity. It’s not surprising that it’s been largely erased from stories and teachings. But the Pleiades holds sacred knowledge for us, and the spider – whom we call go’gwejij – is the one who knitted and wove that eight-pointed star. That star itself is a pathway for humanity on how to live in balance.

As I deepened my understanding, we looked to language and teachings together. I discovered that the petroglyph forms the structure of a moon lodge. That’s where all the feminine teachings happen, where the sacred feminine is honoured. Some Elders have been working to rebuild these moon lodges, bringing back those teachings. I was fascinated because, at the centre of that lodge – and of the Sacred Fire – is the spiral in the eight-pointed star. I was engaging in Sacred Fire as pedagogy throughout my learning, and I kept asking, How does this all connect? What might I learn from this?

Miigam’agan said, This petroglyph is a sphere – it’s multi-dimensional, not one-dimensional or two-dimensional, like the concept of Metuaptmumk. Now, two-eyed seeing, or Etuaptmumk, is a guiding principle introduced by Murdena Marshall and Albert Marshall in 2004. It’s the idea that we look through one eye with the Western worldview and through the other with an Indigenous worldview, bringing both together to understand knowledge systems in a more expansive way. Two-eyed seeing gives a broader lens, especially in integrative science, but Metuaptmumk takes it further; it expands to all-around seeing, a 360̊ lens. The “meh” sound adds the dimension of creation energies, multiple perspectives, and multiple dimensions.

Miigam’agan explained that Etuaptmumk sits at the centre of this process. The first stage, Ketuaptmumk, is about entering an inquiry, whether research, evaluation, or knowledge gathering. It’s the preparation stage of setting intentions, doing ceremonies or fasting, reflecting inward, discerning who you are coming into the process as, and understanding your biases, expectations, and comfort with discomfort. Ketuaptmumk is about looking inward, understanding how we show up, and doing the healing work that makes ethical engagement possible. Without that inner work, even well-intentioned systems change, research, or evaluation can unconsciously perpetuate harm. So this work is essential before engaging with others who may have different worldviews.

The next stage, Etuaptmumk, is where two-eyed seeing truly comes to life. Albert Marshall told me two-eyed seeing was introduced as a way to recognize Indigenous knowledge systems alongside dominant Western knowledge. But many use it only in theory, without action or accountability. Metuaptmumk expands this: it guides people into action, relationship with Indigenous knowledge, the natural world, and the spiritual realm. It reminds us that Indigenous knowledge is vast – just like our languages – and that we need new ways of thinking, doing, knowing, and being.

The sacred feminine, through rematriating our language, reshapes this process, grounding Metuaptmumk in relationality, care, and balance. Jim Dumont (also known as Onaubinisay) talks about different intelligences – physical, mental, emotional, spiritual – and Miigam’agan adds that at the centre of these intelligences is love. Love holds everything together. This is the foundation for engaging in dialogues, research, and evaluation in a multi-dimensional, ethical way.

Metuaptmumk teaches us how to show up, hold space, and navigate tensions. Jane Middelton-Moz calls this principle “honest kindness and kind honesty.” When we speak difficult truths, we do so with kindness; and ignoring difficult truths is unkind. This prepares us to facilitate conversations, bring together diverse knowledge systems, and hold sacred ethical space, as Willie Ermine describes it.

“When our breath meets in shared space, that’s where spirit shows up, and we are responsible to each other. Metuaptmumk gives us the tools to navigate these spaces, to hold space ethically, and to do the inner work necessary to engage in evaluation, inquiry, or research without causing harm.”

– TerrellynMiigam’agan often talks about shared space. She told me about a disagreement with her brother over the pronunciation of the name of their First Nation community, Esgenoôpetitj. Their father reminded them that the initial breath – the “Es-” – is a silent release, a form of accountability. When our breath meets in shared space, that’s where spirit shows up, and we are responsible to each other. Metuaptmumk gives us the tools to navigate these spaces, to hold space ethically, and to do the inner work necessary to engage in evaluation, inquiry, or research without causing harm.

Spoken Insights – “The Spider and the Star”

The story of the petroglyphs reminds us that knowledge is layered. Some parts are remembered, others are erased or silenced. Restoring balance requires looking closely at what has been hidden and asking why.

“The Spider and the Star” – Terrellyn Fearn, Excerpt from the Indigenous Insights Podcast, S01E08, 21:05-22:41

- How might bringing erased or overlooked teachings into view shift how we understand balance, responsibility, or accountability in our work?

- What pathways of balance can you identify in your own practice, and who are the “weavers” holding them together?

Gladys: As you were sharing, I was picturing saying this word. Met – I’m not going to say it right. I’m going to try. Metuapanuk?

Terrellyn: Metuaptmumk (Meh-do-opt-da-mumk).

Gladys: Metuaptmumk, it’s like the air that’s around us. It’s holding everything. You shared the teaching around the breath, that you breathe out and breathe in, and I breathe out and breathe in, and it creates the space of relational accountability. We have a responsibility for how we show up in these spaces and how we prepare ourselves and how we take care of ourselves as practitioners, as people who are living and breathing and doing this kind of work in knowledge gathering, inquiry, evaluation, innovation. We have a responsibility to show up to the best of our ability, and to do no harm in that work. How do we prepare ourselves? Because that’s the first responsibility.

Terrellyn: I always say we need a strong foundation of self-inquiry and reflexive praxis. Many people don’t learn that explicitly – they often learn it the hard way, through their own practice. You and I have shared experiences in social work and the social sciences, where reflexive practice is emphasized, but for folks in other disciplines doing this kind of work, it’s not always taught. And it can be challenging – it’s one thing to say, “Do this inner work,” and it’s another thing to actually do it.

I think about the difficult conversations I had with my parents. It took courage to go deep into those experiences, to face the discomfort, to unpack internalized colonization and intergenerational trauma. That’s why I share my experiences – because going through this work cultivates humility and helps us understand what’s truly needed.

That’s also why tethering to the Sacred Fire is so important. In the first part of the Metuaptmumk process, we gather around the Sacred Fire and teach people how it connects to the fire within them, their spirit. When people enter Metuaptmumk and prepare themselves for inquiry, we’re asking them to connect to themselves, to each other, and to Creation. It’s about showing up authentically with your whole self.

This takes work and time. And as we do that work, we evolve spiritually as two-legged beings, as people on this journey of inquiry. Doing this inner work opens up our relationship with the cosmos – because that’s where knowledge resides. Our ancestors hold that wisdom, and to access it, we need to do the preparation. We carry trauma in our bodies, blockages in our internal systems, and we have to move through those to access that realm of knowledge. Again, as Miigam’agan says, we have to unwind the colonization within us in order to rebuild and connect.“Metuaptmumk reminds us that data is everywhere: in the trees, in the seen and unseen, in dreams, in intuition – the things that colonization has tried to disconnect us from. ”

– Terrellyn

If we’re entering a space of research, evaluation, or inquiry without doing that inner healing work, we simply won’t have access to that innate wisdom or the spiritual realm. That’s why this work is essential. It opens us to a richness of data – not just numbers or metrics, but the wisdom of our ancestors. Metuaptmumk reminds us that data is everywhere: in the trees, in the seen and unseen, in dreams, in intuition – the things that colonization has tried to disconnect us from. Practices like the Sacred Fire reconnect us to those ancient Indigenous ways of coming to knowledge.

So when we ask ourselves, Where does knowledge sit? Where do we find data? How do we understand impact and success in our evaluation work? – we have to access these realms. Especially now, with the Seven Fires Prophecies coming to fruition, this connection is vital. I think of our Haudenosaunee faith keeper, Kevin Dear, who sits on our Elder circle. In a workshop, he said, The universe is my university. <laughs> And as a grad student, I just laughed and thought, Yes, mine too. That’s the beauty of Metuaptmumk. This multi-dimensional process, this expansive way of being and knowing, enables us to live within the universe and learn through it. It’s not just a framework – it’s a way to bring relational accountability, spiritual evolution, and ancestral wisdom into the work we do in inquiry, evaluation, and innovation.

Gladys: That drives home the point that you shared at the beginning, that two-eyed seeing was embedded within a larger understanding of how we need to show up and how we need to engage in order to access this multi-dimensional space that is part of this rematriation of the sacred feminine. It seems to me that there’s so much further to go when we think about how to prepare ourselves. We are not only individual people who are reconnecting, going deeper within the Nations that we live within, but we also need to engage with the roles that we hold as inquirers, as evaluators, as learners, as storytellers, in order to understand the impact that some of the work that’s happening in the communities is having. There’s so much more that we can access and there are ways of learning that we can strengthen when we understand that two-eyed seeing is the beginning point of understanding this deeper, interconnected multidimensional process.

Terrellyn: When we restore the sacred feminine in the Mi’kmaq language, we unveil Metuaptmumk. Metuaptmumk breathes spirit into complex spaces that have become disconnected from the life force. It provides a pathway to what my beloved late Tuscarora Elder Rose Imai calls “awakening the learning spirit.”

Metuaptmumk is a pathway to transformative change. It’s a pathway to deeper insight, to healing, and to cultivating a sense of belonging in a world of kinship and interconnection. It reawakens this learning spirit by connecting us to ourselves, to each other, to our earth mother, and to all of creation.

I think back to the Seventh Fire prophecy. The human family is at a critical moment. We can continue down a road of destruction, violence, and degradation of our earth mother and all our kin, or we can choose the spiritual path that leads toward lighting the Eighth Fire of peace. Metuaptmumk kindles the embers of that Seventh Fire, guiding us toward that Eighth Fire. Of the prophecy, the late Ed Benton-Banai wrote in 1988 in The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway that there are some who choose neither road, but instead turn back to remember and reclaim the wisdom of those who came before. Metuaptmumk is that pathway – it restores what we have forgotten, bringing us back into relationship with our ancestral knowledge. It’s a bridge to connection[1].

Part of this work is healing our ancestral lineage. We must understand our own stories and the stories of our ancestors. Earlier I shared my Irish lineage; I’ve spent time learning about that history – experiences of colonization and residential schools in Ireland – and about how those experiences carried forward into our lands and communities in Mi’kma’ki. Metuaptmumk reminds us that we need to be in right relationship with our ancestors. We ask them for guidance, for wisdom, for help in moving forward in a good way, but first we must heal ourselves and those lineages.

I want to distinguish between knowledge and wisdom. Knowledge comes from lived experience – but experience alone doesn’t make us wise. <laughs> Wisdom, to me, is healed pain. It’s transforming the negative emotions of our experiences into understanding, into something positive. That’s what healing is. When we do that work – when we heal ourselves and our ancestral lineages – we can show up fully in these spaces, whether we are scientists in a lab, evaluators, or community practitioners.

Metuaptmumk is a process for everyone. That petroglyph I spoke about is a sign for all humanity. In this time of prophecy, when Indigenous Nations’ wisdom and traditions are guiding us forward, Metuaptmumk gives us a pathway to do that work: to connect, to heal, and to bring forth knowledge and wisdom in service of our communities and all of humanity.

Spoken Insights – “Awakening the Learning Spirit”

Metuaptmumk is described as a living pathway that reconnects us to self, others, ancestors, and creation. It is not only about knowledge but about healing, responsibility, and choice..

“Awakening the Learning Spirit” – Terrellyn Fearn, Excerpt from the Indigenous Insights Podcast, S01E08, 42:25-44:09

- How does the idea of “awakening the learning spirit” invite you to reconsider the purpose of your own learning or evaluation practices?

- What does it mean to see knowledge as part of a spiritual or ethical path, rather than only as information?

Gladys: Thank you so much, Terrellyn. These are great insights and opportunities for self-reflection around who we are and how we’re able to show up as evaluators in our work in Indigenous evaluation.

I know that you want to share a story about a beautiful creation that happened as a result of spirit in your work around the Sacred Fire in the last year. So I’ll invite you to tell that story.

Terrellyn: After my 13-moon journey, I was reflecting on all of the knowledge I had gathered – not only trying to decolonize the way I was analyzing this work, but also thinking about how to embed Indigenous ways of analysis. I started asking myself: How do I report this back in a way that honours the teachings? How do I share this knowledge differently?

One of my colleagues, who joined our team about six months ago, is a beautiful seamstress. She makes ribbon skirts, and during our final gathering in June we brought together clan mothers and grandmothers for four days. It was a gathering of sacred energy, the feminine energies of creation.

I invited her into the process and said, Take my knowledge from these four days and create a visual expression of what you are coming to know. I don’t own this process, even though I’ve journeyed for 13 moons. You are here for a reason. What is it that you see and feel that I can’t? She sent me images of what she created, and so many of them mirrored the sketches I had made myself. Together, we created matching ribbon skirts, synthesizing and bringing forth the teachings of that 13-moon journey around the Sacred Fire.

We also made a bundle blanket for the Turtle Island Institute for Indigenous Science. That blanket became the foundational artifact for the journey, holding the knowledge and teachings we had gathered. It really made me think about the ways we share knowledge. In grad school, we’re trained to publish, to write theses, to document things in academic journals – but that’s not the only way to share what we know. In Mi’kmaq culture, we have peaked caps and other cultural insignias that communicate who we are and how we exist in the world. These visual and tactile forms are ways of rematriating knowledge – bringing back teachings and wisdom in ways that honor our ways of being.

That’s why I’m so grateful for this podcast, Gladys. It’s an opportunity to share knowledge orally, to storytell, and to express deep wisdom in a way that isn’t confined to the written page. For so long, Indigenous people were forced to convey knowledge through systems that weren’t ours. Now, there’s space to reclaim that knowledge in ways that are alive, relational, and generative.

From Insight to Action

Knowledge can live in sound (as in podcasts), or touch (as in textile art), not only in written reports.

Try to translate one active project into a tactile or multi-sensory artifact (e.g., ribbon panel, bundle square, audio story). Co-create with a community artist. Document what the artifact teaches that conventional reports miss.

Gladys: Thank you. Creative processes for sharing and expressing are something that I’m truly passionate about. I loved hearing about the different ways that you’ve been thinking about your inquiry through ribbon skirts and bundle blankets, in ways that are in alignment with knowledge systems that we’re trying to work within.

This also makes me think about this podcast, these conversations, as creative expression. I work within poetry and have led collective poetry exercises, but the beauty of that is actually when it is spoken, when the words that are on the paper are expressed, when the breath is offered into the space, where we could all witness that learning and that journey. I’m inspired by the different ways that you’ve been able to share story.

I’m sure your thinking will continue to expand around your journey with the sacred feminine and rematriation and the depths of language in this work. But I want to ask if there’s anything that you wanted to share as you wrap up today.

Terrellyn: I’m excited that we’re talking about creativity and artistic expression. When I was young, I read a quote from the Métis leader Louis Riel: “My people will sleep for a hundred years, but when they awake, it will be the artists who give them their spirit back.” I remember thinking, Wow, that’s profound. Who are these artists who will do that? It wasn’t until my late twenties and early thirties that I realized: we are all those artists. It’s about cultivating the creative capacities within each of us.

Metuaptmumk is a pathway for all-around seeing, for whole-person development, and it helps us unlock these creative capacities. Creativity is critical because it’s our direct access to spirit. But to fully access it, we have to turn ourselves inside out. Trauma, pain, and the blocks we carry in our bodies and spirit stifle our creativity and imagination. Metuaptmumk guides us through that process, helping us move through those barriers so we can connect to the fullness of our creative and spiritual potential.

Turtle Island Institute for Indigenous Science is going to embody this approach. We’re preparing a 13-moon, four-season artistic journey to communicate Indigenous scientific knowledge through creative expression. We’ll be journeying with Indigenous scientists, Western scientists, academics, Elders, and young people to harvest and build a birch bark canoe. Metuaptmumk will guide the process, and we’ll also use it as our evaluative framework, ensuring that the work is grounded in relationality, care, and multi-dimensional understanding. The pathway of Metuaptmumk is so needed in these times.

I want to thank you, Gladys, for this conversation. I remember Senator Murray Sinclair, Chair of Canada’s Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission, speaking at an innovation gathering. He said, “Innovation isn’t always about creating new things. Sometimes innovation involves looking back at the old ways and bringing them forward.” That’s exactly what Metuaptmumk allows us to do. We are rematriating our language, decolonizing it, reconnecting to ancestral knowledge and wisdom, and restoring the sacred feminine. For so long, we’ve been told to think outside the box, but when we exist outside the box, we often lose our connection. Now is the time to center our Indigenous ways of knowing – inside the circle, inside the lodge, around the Sacred Fire of Peace. Through Metuaptmumk and all-around seeing, that’s exactly the work we are stepping into.

Gladys: Wow, I cannot wait to hear the incredible stories that come out of that experience! Kinanaskimotin. I’m so grateful for you. Thank you for spending time with me today, Terrellyn. That’s it for this week. I look forward to sharing the space with you again soon. Ekosi.

The Episode

Listen to the full conversation featured in this chapter:

Footnotes

- Edward Benton-Banai, The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway, 2nd ed. (University of Minnesota Press, 2010). ↵