Context

9 Systems Snapshot: The Widening Road of Inclusion in Canada

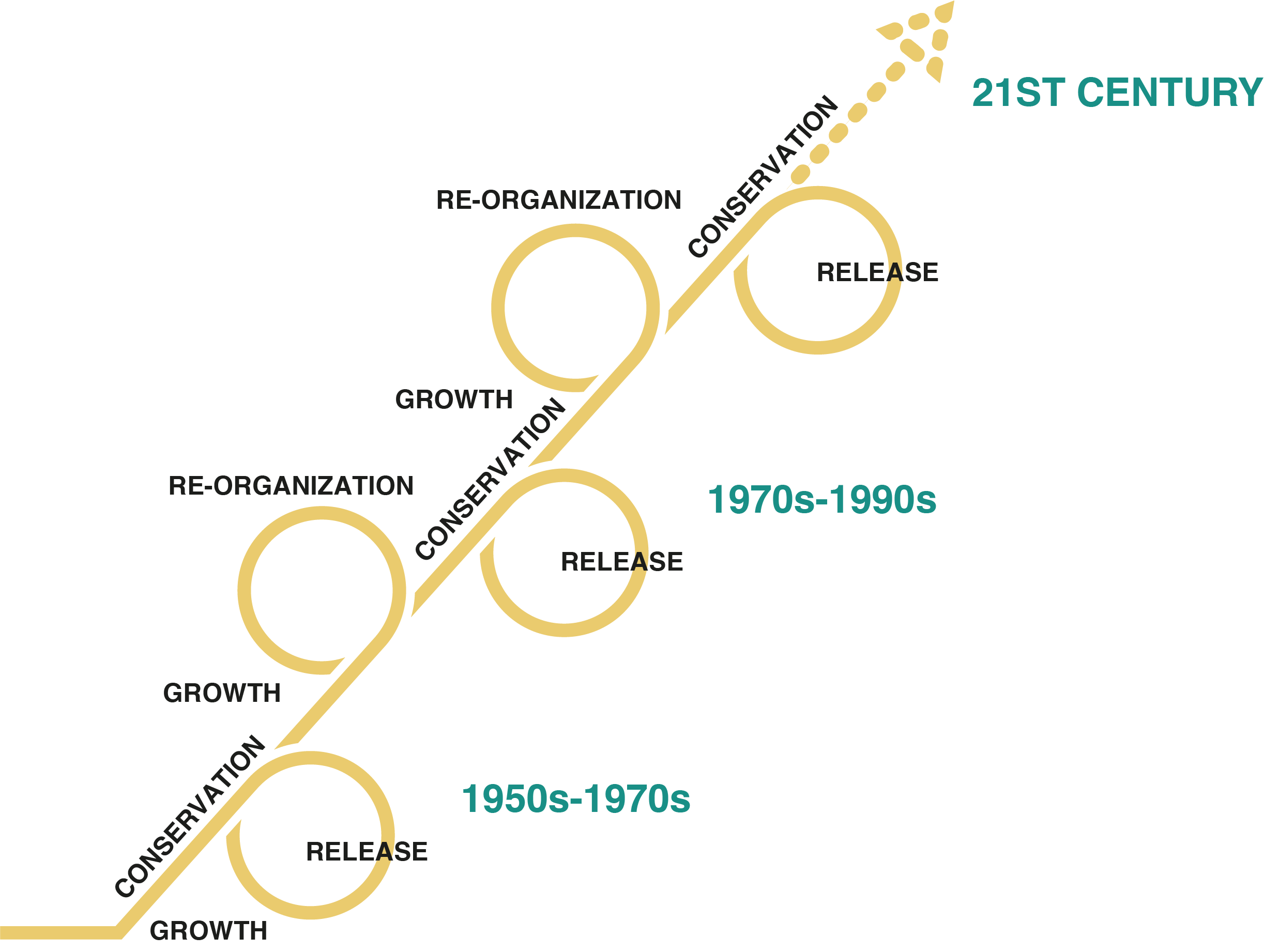

A commonly used tool in the analysis of social movements or systems change is the “adaptive cycle”, adapted from Canadian ecologist Buzz Holling’s work on forest change.[1] Using a mobius loop, the tool is used to explore how movements emerge in response to conditions that have over time become stale, complacent, or otherwise stagnantly ‘mature’, to the point of being ripe for disruption or destruction. We can apply this metaphor in the image below to thinking about how social movements have emerged, evolved, matured, then entered a state of ‘release’ (prompted by external conditions) cleaving to newer social movements emerging to think differently about accessibility. As we look back on the last many decades, there have been multiple cycles of growth, conservation, release and renewal.

Adaptive Cycle Image Description:

Starting at the bottom, the first adaptive cycle circuit of growth, conversation and release occurred from the 1950s to the 1970s. During this period, barriers, physical and otherwise, were ubiquitous. There was a rise of the welfare state and Institutionalization as a legacy of the early 20th century was increasingly recognized as flawed. The dominant mental model was ‘Doing For’, where Persons with Disabilities (PWD) were infantilized and the PWD voice was ignored.

Moving upwards to the 1970s to 1990s, there was the rise and establishment of the self-advocacy movement and emergence of a rights-based framework. Barrier-free pathways in many realms started to emerge and the first wave of building codes and design standards came into existence. There was a push of de-institutionalization and flourish of group home models. The dominant mental model became ‘Doing With’ or what we might now call ‘allyship’.

As we progress through the 21st century, the latest round of the adaptive cycle has continued to feature significant shifts. There has been a rise of universal and inclusive design frameworks, and barriered environments, both physical and virtual, have started to become non-compliant and even taboo. There has been an increasing heterogeneity and intersectional recognition, as well as the rise of EDI or DEI. PWD-led entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship has increased and the dominant mental model is now ‘Nothing About Us Without Us.’ More People with Diabilities are in positions or leadership and influence, and are defining the terms, norms, and expectations.

The self-advocacy movement, starting in the 1980s, profoundly changed these institutional settings (most of the more formalized settings were shuttered permanently), as well as public understanding and framing of disability.[2] People were speaking for themselves and asserting their rights as citizens. Freedom and dignity were primary considerations within the disability-serving segment of community services, including in the context of group home settings.

Increasingly, disability support focuses on the unique needs, capacities and desires of the individual, such that people can take control over, and responsibility for, their own lives. This approach goes by various monikers – self-determination, consumer direction, individualized support, user-centered or bespoke solutions, etc. The climb up the ladder of participation for people with disabilities is a more difficult journey than for most, partly because of ableism and accessibility barriers, but also because it is difficult for adults with profound intellectual (and multiple) disabilities (PI(M)D) to achieve full autonomous participation. Such adults are dependent on others in every aspect of their lives, and as such, others control their ability to participate in everyday life decisions.[3]

An important part of this paradigm shift from institutional control to individual agency is a funding model shift from the majority of funding flowing to and through agencies, to a model that sees most of the funding transfer to individuals, so they are more empowered to seek out the community supports they require and admire.

The nomenclature has also adapted with the times. “Handicapped” has in most contexts given way to “disabled”, which in turn has in many instances given way to terminology of “person with a disability” or “living with a disability”, which emphasizes the person first and the disability second.[4] It also emphasizes that the person is not defined by their disability, but rather is attempting to live a full and flourishing life, notwithstanding being challenged by the dimension of disability they are experiencing. As with other equity-deserving communities, disability rights and representation discourse are shifting rapidly. “Differently abled” was used for a time. More recently, the terms neurodiversity and physical diversity have become more common.

One of the big shifts in our society’s approach to disability is moving away from a medical model, toward a social model.[5] The medical model views disability as a medical problem that needs to be fixed or cured, or as an individual deficit or impairment that must be treated or managed. A social model of disability views disability as a social construct, rather than a medical or individual problem. According to this model, disability is caused by the interaction between an individual’s physical, sensory, or intellectual impairments and the societal and physical barriers that limit their participation in society. In other words, disability is not an inherent characteristic of an individual, but rather the result of a lack of accessibility and inclusiveness in society. But as one commentator notes “the existing social model of disability, whilst preferable to the medical model, remains framed around the concept of “impairment”.”[6] Another critique of the social model is that it can oversimplify the experiences of people with disabilities, ignoring the fact that some disabilities do have intrinsic physical or psychological aspects that can limit participation in society. Additionally, some argue that the social model can be too focused on external barriers, such as the built environment, and overlook the internal barriers, such as attitudes and beliefs.

Another paradigm shift still underway is the move away from reductionist models toward particularistic, phenomenological approaches (what we might call bespoke or user-centered design, development, and programming); Persons with disabilities designing or co-designing spaces, technologies and policies, instead of having these things designed for them by other ‘experts’. This shift parallels the backlash in other realms – responsible tech, for example – against an outdated engineering paradigm that seeks to place “rationality” (with its largely male, ableist, heteronormative, and computationally-confident assumptions) above the fray of human interaction, public welfare considerations, or empathy-seeking.[7] Along similar lines, looking at the convergence of inclusive and universal design paradigms with techno-futurism, disability is increasingly positioned as an innovative research area that leads designers to new technological discoveries, rather than as a medical problem to be fixed or cured.[8]

The “Disability Community”

While the term “disability community” is often used as shorthand for “persons with disabilities”, it is a stretch to say that there really is a readily identifiable “disability community”. More accurately, there are many sub-communities, and many people with disabilities do not necessarily identify with any disability community. The Deaf community is notable in terms of apparent cohesion and self-identification. Other communities identify more along movement, tactical focus, or quasi-ideological lines, like the mad movement, which is confronting the psychiatric paradigm as having been overtaken by pharmaceuticalization.

Much like how the LGBTQI community has appropriated and repurposed the originally-derogatory “queer” label, some in the disability community today are re-purposing language. The “crip” movement and “Mad Pride” movement push for broader meaningful participation and flourishing. As mad movement activist and writer Lisa Archibald explains:

The term “mad” has been reclaimed intentionally as a deliberate interruption or sabotage of the dominant psychiatric perspective. It challenges the entire basis of the medical framework which is that people have illnesses or disorders. Prior to the last 200 years in history, “madness” was a widely accepted term in society and was not a medical term. The reclamation of “mad” is a provocation to psychiatry as it is a complete rejection of their diagnostic expertise and power.[9]

There is even a “crip futures” movement looking at futures studies, architecture, technology, and design through a disability lens. Queer/feminist/crip scholar Alison Kafer describes it as “a longing for a future in which disability is welcome and in which the collective knowledge and practices of disabled people shape the future structures.”[10]

Despite society’s attitudes having shifted positively over the past century, 30% of persons with disabilities still report being treated badly or differently, often because of ideas, beliefs or attitudes that others have about disabilities; and the majority of complaints to the Canadian Human Rights Commission are on grounds of disability-related discrimination.[11]

The federal government produces a booklet called A Way with Words and Images, which recommends current and appropriate language to accurately and respectfully portray and describe people with disabilities.[12] Among the helpful suggestions in the booklet is avoiding normative statements about people with disabilities being either super-achievers or tragic figures – words like “brave,” “courageous,” and “inspirational” can be patronizing[13] and serve to reinforce the deeply embedded (but socially and economically unhelpful) mental model that we need barriers in order to be awed and inspired by a disadvantaged minority struggling to overcome. Our psychological and axiological craving for stories of pathos, bravery, and redemption can be unwelcome baggage in this context.

- As one example of the Adaptive Cycle, Gunderson, L. H. and Holling, C.S (Eds.). (2009). Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Island Press ↵

- As an example, BC’s story of the rise of self-advocacy among persons with disabilities, documented in: Developmental Disabilities Association. (2022, August 11). Doing the Impossible: The Story of the Developmental Disabilities Association [film]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-MJVoS9_bL8 ↵

- Lena Talman, Jonas Stier, Jenny Wilder, and Gustafsson, Christine. (2021, March). Participation in daily life for adults with profound intellectual (and multiple) disabilities: How high do they climb on Shier's ladder of participation? Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 25(1):98-113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629519863959 ↵

- The shift away from “disabled” is not absolute and some are pushing to reclaim it: Ashton. (2022, July 2). Say Disabled: Disabled is Not A Dirty Word [TikTok Video]. @ radiantlygolden. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMjgCjkaR/ ; Matthew and Paul (2023, July 16). Disabled [TikTok Video]. @MatthewAndPaul. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMjtd3b8G/ ↵

- Mohanty, Changing the Conversation on Chronic Illness, 2022. ↵

- Lisa Archibald. (2021, September 21). Mad Activists: The Language We Use Reflects Our Desire for Change”, Mad in America [blog]. https://www.madinamerica.com/2021/09/mad-activists-langauge/ ↵

- An incident involving Google engineer James Damore is emblematic. In a letter to fellow employees, he urged them to “de-emphasize empathy,” warning that “being emotionally unengaged helps us better reason about the facts.” The authors further note that male engineers are four times as likely as male lawyers to reject proactive workplace equity, diversity, and inclusion actions. Joan Williams and Marina Multhaup. (2017, August 10). How the Imagined “Rationality” of Engineering Is Hurting Diversity — and Engineering. Harvard Business Review. ↵

- Bess Williamson. (2019). Design for All: An excerpt of Bess Williamson’s Accessible America shows how accessible design is innovative and inclusive. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/books/excerpts/entry/design_for_all ↵

- Archibald, Mad Activists, 2021. ↵

- Alison Kafer. (2013). Feminist, Queer, Crip. Indiana University Press. ↵

- Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC). (2022). Canada’s Disability Inclusion Action Plan, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/disability-inclusion-action-plan/action-plan-2022.html ↵

- Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. (2022, December 16). A Way with Words and Images. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/disability/arc/words-images.html ↵

- Imani Barbarin. (2021, November 12). Is your own #inspiration the only value you see in #disabled people? [TikTok Video]. @crutches_and_spice. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMjtuL6aW/ ; Spencer West. (2023, June 13). Not a compliment [TikTok Video]. @Spencer2TheWest. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMjtujGMC/ ↵