Domain 3: Accessible Wayfinding

40 Communication

While communication is a dimension of accessibility that suffuses virtually every other realm described in this Scan, it is worth mentioning in its own right. There are three innovations, in particular, that have revolutionized the accessibility of communications – sign language, braille and closed captioning. Digital communications will be addressed in a subsequent section.

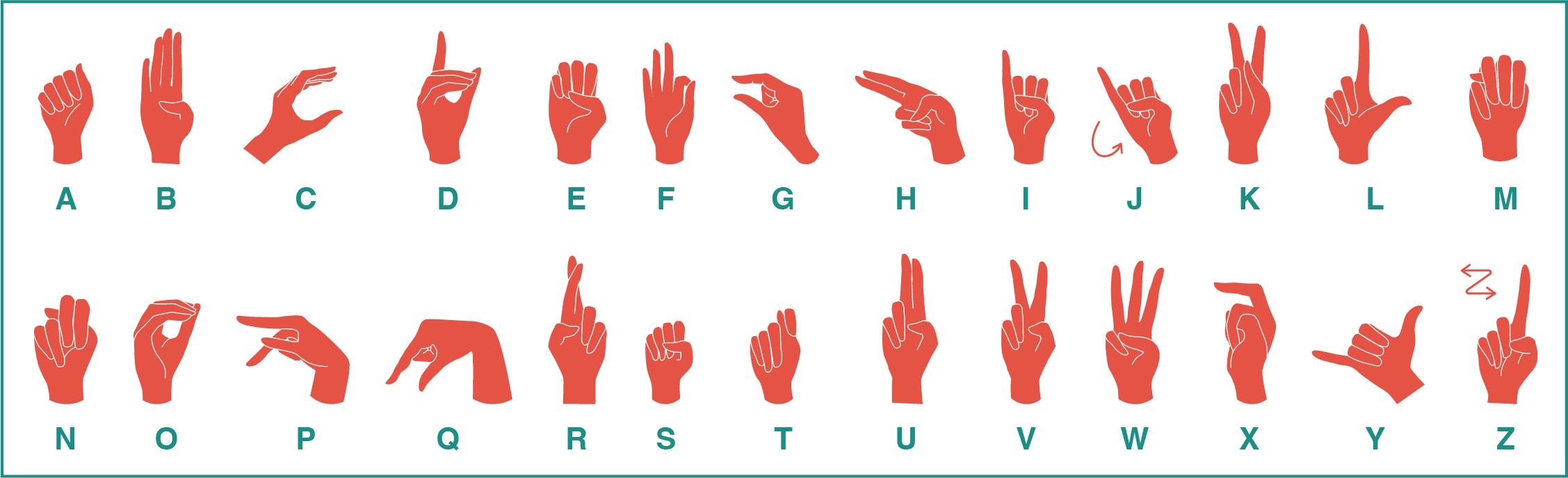

In the early days of the schools for the deaf, there were many different sign languages being used across Canada. However, as more and more hearing impaired students began attending the schools in the 19th Century, a standardized sign language began to emerge. This new language eventually became known as American Sign Language, or ASL.[1] Transformative in its impact, today ASL is recognized as a complete and independent language, with its own linguistic structure, vocabulary, and cultural norms, and is used by millions of people in North America. The ASL Alphabet is shown in the image below.

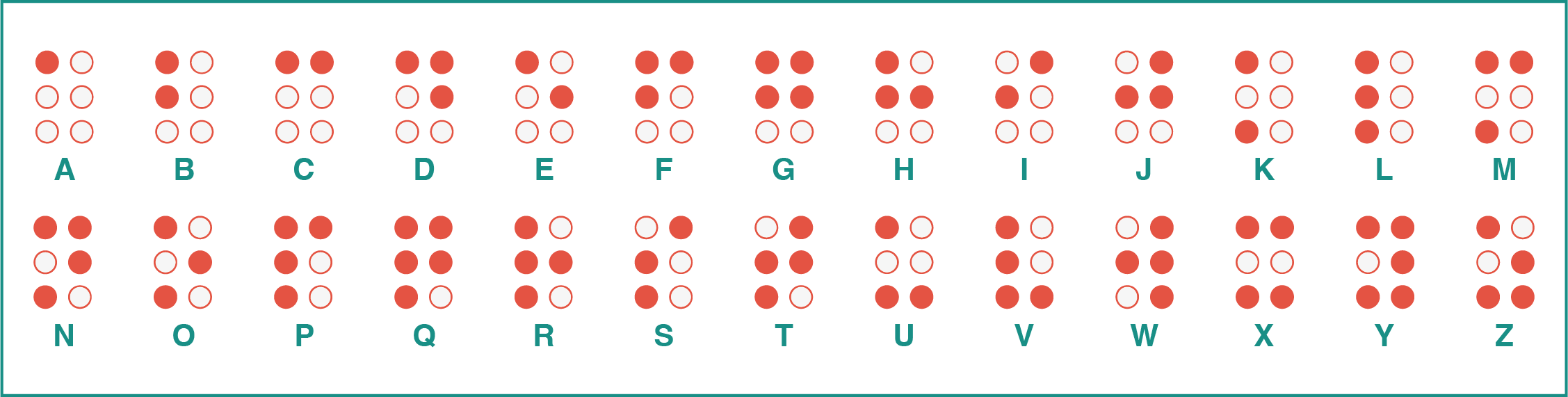

Another major innovation was Braille, as shown in the image below. In 1821, Louis Braille was introduced to a military code developed by Charles Barbier, which was intended to be read by soldiers in the dark using raised dots and dashes on a flat surface. Braille was intrigued by the idea and began working on a modified version of the code that could be used for reading and writing more general literature. Braille spent several years refining the code, which eventually evolved into the system of six dots that we know today.

Closed captioning, initially developed in the 1970s, is the process of displaying text on a television, movie, or video screen that corresponds to the audio track. Initially used to provide access to content for individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing as well as for non-native speakers, it has proved to be an indispensable universal design spec on all broadcast motion-picture-based entertainment and information, helpful for people in noisy environments, who have trouble discerning accents, to enhance retention (some pedagogical theories contend that information absorption is best when simultaneously heard and read), or for people living with certain cognitive or learning disabilities. Closed captioning, extended now beyond broadcast, cable and satellite cable services to streaming platforms, is now a requirement for all publicly distributed media regulated through the Canadian Broadcast Standards Act.[2] A related communications accessibility tool – the web-based Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) – provides live, word-for-word transcription in both official languages of speech to text so that individuals can read what is being said at public events, in group settings and at personal appointments on a laptop or a larger screen. This is critical for accessible events planning, as not all people who are deaf or hard of hearing can use ASL.[3]

- ASL was heavily influenced by French Sign Language (LSF), as many of the early teachers at the American schools for the deaf were trained in LSF. Over time, ASL began to diverge from LSF, and by the mid-20th century, it had become a distinct language with its own grammar and syntax. For more, visit: DawnSignPress.(2016). History of American Sign Language [website]. https://www.dawnsign.com/news-detail/history-of-american-sign-language ↵

- Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. (2020, June 9). TV Access for People who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing: Closed Captioning. https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/info_sht/b321.htm ↵

- The Canadian Hearing Society. (2014). Position Paper: Challenges and Issues Regarding Communication Access. https://www.chs.ca/canadian-hearing-society-position-paper-challenges-and-issues-regarding-communication-access ↵