2 Historical Perspectives in ECE

Authored by Gayle Julian, Reviewed by Sophie Truman, Edited by Jean Doolittle Barresi

Key Points

Key Points

- Early childhood education has a rich history spanning centuries, with influential thinkers and practitioners shaping its philosophical and research-based foundations.

- Various theories of child development, such as cognitive, behavioral, social learning, sociocultural, psychosocial, attachment, and ecological systems theories, provide frameworks that inform high-quality early childhood programs and practices.

- The field of early childhood education continuously evolves in response to societal changes, new research, and trends, such as professionalization of the workforce, equity, diversity, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Terminology Found Throughout This Chapter:

There are several key terms mentioned in the chapter that are important for understanding the historical and theoretical foundations of early childhood education. Some of these key terms include:

Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) – a concept based on research and theory about how children learn and develop best.

Constructivism – the idea that children actively construct their own knowledge through experiences with the world.

Schemas – cognitive frameworks or concepts that help organize and interpret information.

Assimilation – the process of incorporating new information into existing schemas.

Accommodation – the process of modifying existing schemas to fit new information.

Reinforcers – stimuli that increase the likelihood of a behavior being repeated.

Intrinsic Motivation – the internal drive to engage in a behavior for its own sake.

Scaffolding – the support provided by a more knowledgeable other to help a child learn a new skill or concept.

Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) – the difference between what a child can do independently and what they can do with assistance from a more skilled individual.

Attachment Patterns – the type of bond formed between an infant and their primary caregiver, which can be secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-resistant, or insecure-disorganized.

2.1 Historical Roots

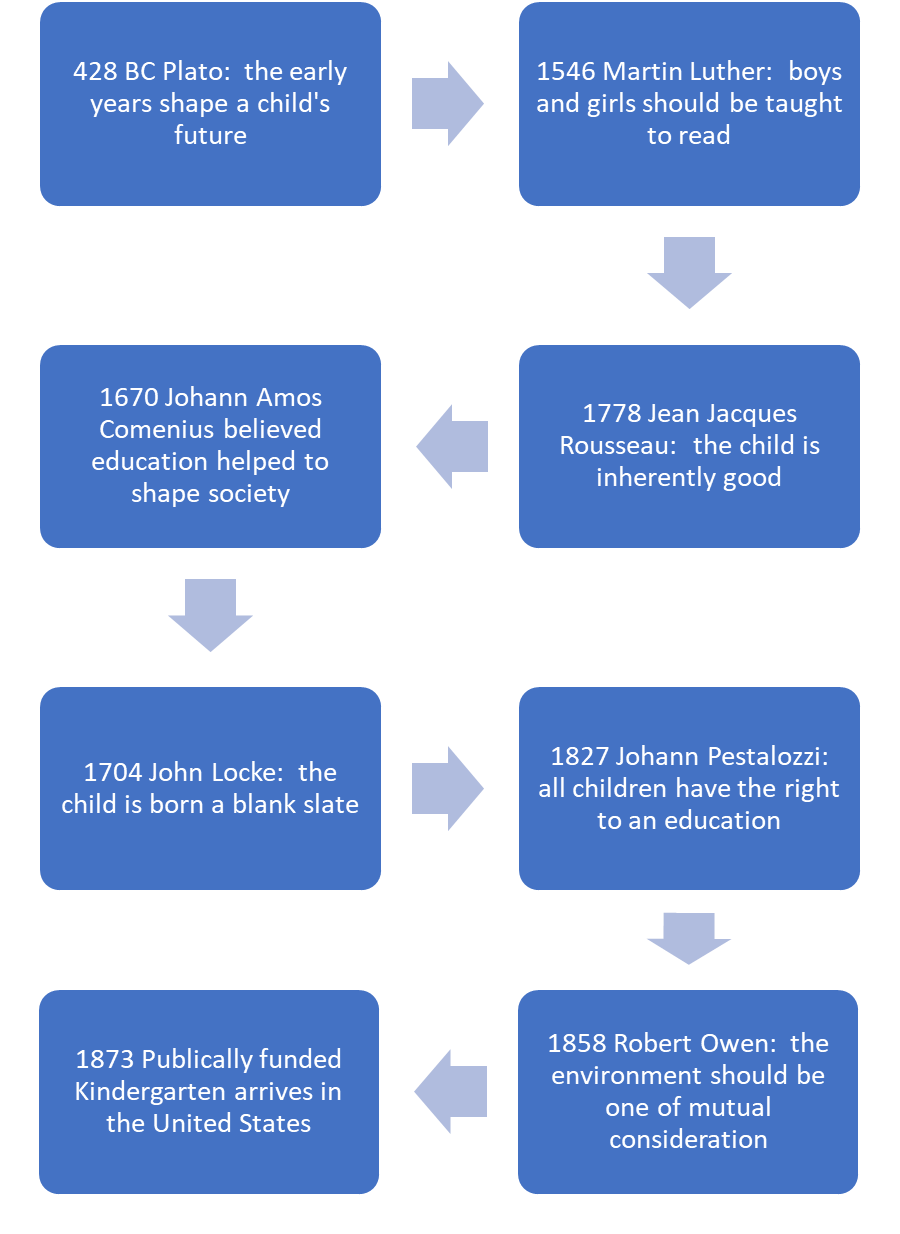

The roots of early childhood education can be traced back to ancient Greek philosophers such as Plato (428-348 BC), who believed that the teacher’s role was to guide children through play towards their life goals. Over the centuries, many notable figures have contributed to the development of early childhood education, including:

- John Amos Comenius (1592-1670), a Czech philosopher who emphasized the importance of early education

- John Locke (1632-1704), a British philosopher who believed that children are born as “blank slates”

- Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), a Swiss philosopher who advocated for child-centered education

- Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852), a German educator who founded the first kindergarten

- Jean Piaget (1896-1980), a Swiss psychologist who developed the theory of cognitive development

- Erik Erikson (1902-1994), a German-American psychologist who proposed the psychosocial theory of development

These influential thinkers and practitioners have shaped the philosophical and research-based foundations of early childhood education, emphasizing the importance of play, child-centered learning, and developmentally appropriate practices.

Figure 1.3 Notable Historical Thoughts about Early Childhood Education

The Origins of Child Care in the United States

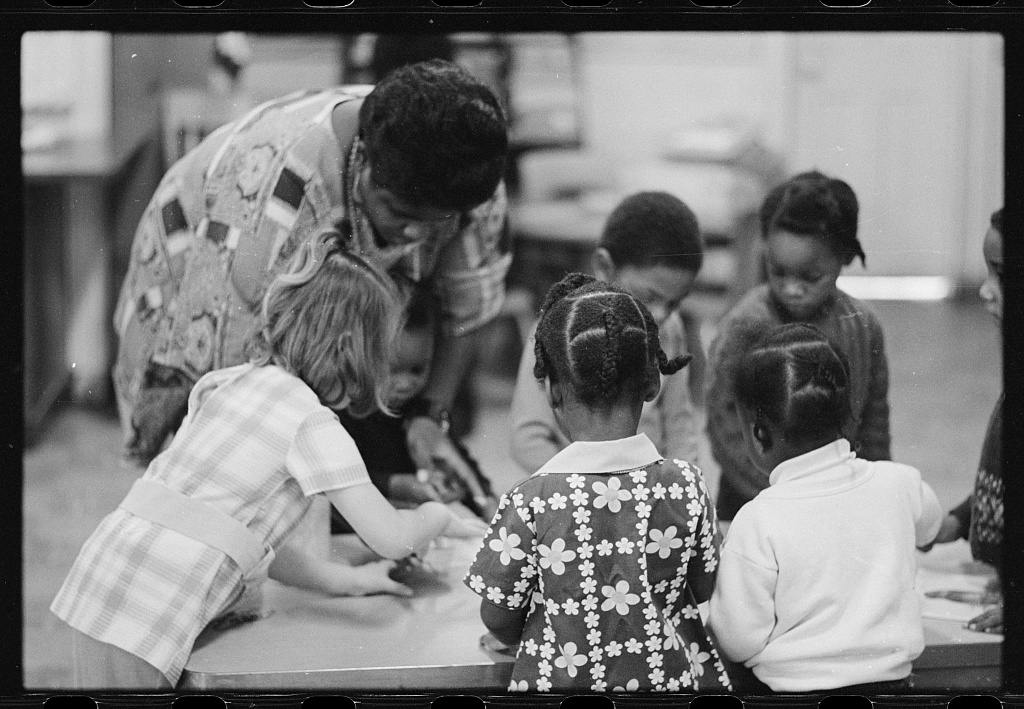

Child care in the United States has evolved over time in response to societal changes and the needs of working families. Key milestones include:

- 1893: The National Federation of Day Nurseries, the first nationwide organization devoted to child care, was established in New York.

- 1912: The U.S. Children’s Bureau was created to set policies for quality child care.

- 1930s: The Emergency Nursery Schools (ENS) program was established during the Great Depression but faced challenges due to high staff turnover rates.

- 1940s: During World War II, the need for child care increased as women entered the workforce to support war efforts.

- 1950s: The child care tax deduction was introduced, allowing low to moderate-income families to deduct child care expenses from their income taxes.

- 1960s: Federal support for child care was tied to policies encouraging low-income women to enter the workforce.

- 1980s: The Child Care and Development Block Grant was passed, allocating funds to support individual states in providing child care.

- 1990s: Welfare reform initiatives, such as the Family Medical Leave Act, provided some child care relief for families.

Today, the child care system in the United States remains fragmented, with ongoing efforts to improve access, affordability, and quality for all families.

Image 1.8 A Historical Moment is licensed under CC by 1.0

Government Funding that Supports Early Learning

The federal government has invested in child care and early childhood education programs for over 80 years to support parents and children. Key funding initiatives include:

- 1933: The Emergency Nursery School program provided child care for children of people working government-paid jobs during the Great Depression.

- 1935: The Aid to Dependent Children program was included as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal.

- 1960s: Head Start was established to prepare children from low-income households for elementary school.

- 1974: The Social Services Block Grant was created to support parents in the workforce by providing child care services.

- 1990: The Child Care and Development Block Grant program was extended to families with incomes above the previous guidelines.

- 1996: The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program was introduced as part of welfare reform under President Bill Clinton.

In recent years, funding for programs like Head Start and the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) has increased to serve more children and families. However, the need for affordable, high-quality early childhood education remains a pressing issue.

Image 1.9 Mrs. Schroeder goes to work is licensed under CC by 1.0

Educational Trends That Have Influenced Early Childhood Education

The field of early childhood education has been shaped by various educational trends and societal changes over time. These trends have influenced policies, practices, and public perceptions of early learning. Some notable trends include:

- Increasing recognition of the importance of early childhood education, as highlighted by President Barack Obama’s 2013 State of the Union address

- Growing emphasis on school readiness and the development of academic skills in early childhood settings

- Emergence of quality rating and improvement systems (QRIS) to ensure consistent quality across early childhood programs

- Professionalization of the early childhood workforce through initiatives like the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) Power to the Profession

Power to the Profession

One of the most significant trends in early childhood education today is the movement to professionalize the workforce. The Power to the Profession initiative, led by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), aims to establish a unified framework for career pathways, knowledge and competencies, qualifications, standards, and compensation for early childhood educators.

The initiative’s goal is to ensure that all early childhood professionals have the necessary skills, knowledge, and support to provide high-quality care and education to young children. By defining the profession and creating a shared understanding of what it means to be an early childhood educator, Power to the Profession seeks to improve the status, recognition, and working conditions for those in the field.

The Power to the Profession framework emphasizes the importance of:

- Consistent and equitable preparation and qualification requirements for early childhood educators

- Clearly defined roles and responsibilities for different levels of the profession

- Appropriate compensation and benefits that reflect the value and importance of early childhood educators’ work

- Ongoing professional development and support to ensure educators have the knowledge and skills needed to support children’s learning and development

As the early childhood education field continues to evolve, initiatives like Power to the Profession play a crucial role in ensuring that the workforce is well-prepared, supported, and recognized for their vital contributions to children, families, and society as a whole.

Societal Changes

Many of the historical trends discussed in this chapter continue to influence early childhood education today. For example:

- The importance of play, as emphasized by early philosophers like Plato, remains a central tenet of developmentally appropriate practice

- The belief that early learning lays the foundation for future education and success continues to drive investments in early childhood programs

- The need for nurturing and supportive learning environments, grounded in historical theories and research, is still recognized as essential for children’s optimal development

As society evolves, new trends and challenges emerge, such as the impact of technology on young children’s learning and the need for culturally responsive and anti-bias curricula. The COVID-19 pandemic has also brought unprecedented challenges and changes to the field, highlighting the importance of adaptability and innovation in supporting children and families.

Reflection

- What societal changes have occurred over the past 10 or 15 years that you feel have influenced the field of early childhood education?

2.2 Key theorists and their contributions

Image 3.2. Photo credit: omarmedina films on Pixabay is licensed under CC by 1.0

Image 3.2. Photo credit: omarmedina films on Pixabay is licensed under CC by 1.0

Several prominent theories have shaped our understanding of child development and informed best practices in early childhood education. These theories provide frameworks for creating effective learning environments and supporting children’s holistic development.

Cognitive Developmental

Developed by Jean Piaget, cognitive developmental theory focuses on how children think, learn, and acquire new knowledge. Piaget proposed four stages of cognitive development:

- Sensorimotor (birth to 2 years): Children learn through sensory experiences and motor activities.

- Preoperational (2 to 7 years): Children engage in symbolic thinking and begin to use language but have difficulty with logical reasoning.

- Concrete operational (7 to 12 years): Children develop logical thinking skills but rely on concrete examples.

- Formal operational (12 years and beyond): Children can engage in abstract thinking and hypothetical reasoning.

Stage |

Sensorimotor |

Preoperational |

Concrete Operations |

Formal Operations |

|

Age |

Birth to 2 years |

2 to 7 years |

7 to 12 years |

12 years and beyond |

|

Behaviors |

Learns about the world through interacting with objects using the five senses |

Begins to engage in symbolic and pretend play, but cannot engage in abstract or logical reasoning |

Begins use of logical reasoning, however, reasoning is limited to objects that can be held or seen |

Engages is abstract and logical reasoning and can apply this type of thinking across contexts |

Table 3.1. Piaget Stage Definitions

Cognitive developmental theory also includes an explanation for how children acquire new knowledge. This is known as constructivism. Constructivism is the idea that children create (or construct) their own knowledge through experiences with the world. Children must use their five senses to interact with objects in their environment in order to gain new information. In this way, they build a conceptual understanding of the world around them. Further, the stage that a child is in determines how a child constructs knowledge. If an infant is in the sensorimotor stage, then they might gain new knowledge about an object by putting it in their mouth. If they take an adult’s keys and start to play with them, they will learn that keys feel cold and hard when placed in the mouth. The next time they see something made of metal, for example, a spoon, they will expect that is cold when placed in the mouth because they learned this from a direct experience with the keys. Reading a book or watching a video about keys will never give the infant this same knowledge because children need tangible, concrete items to help them learn about the world.

Constructivism also dictates that new knowledge builds upon previous knowledge. As children build concepts about their world, they start to organize that information into categories. These categories are called schemas. Schemas are categories of information about a concept or thing. For example, two-year-old Zhe might have a schema about dogs. He might conceptualize dogs as furry, four-legged creatures who have tails. Every time he sees a new kind of dog, he will mentally place it into that category of dog. This process is referred to as assimilation, fitting in new information into what is already known. When Zhe goes on a walk and sees a black lab, a corgi, and a German Shepard, he assimilates these different types of dogs into his schema for dogs. But what happens when he sees a Great Dane? It has four legs and a tail, but due to its size, resembles a horse more than a dog. Zhe must then accommodate this information, therefore changing his previously held ideas about dogs, so that his schema for dogs now includes larger dogs as well. Consider also the first time Zhe sees a cat. It is furry, it has four legs and a tail, but it says “meow” instead of “woof”. Zhe must once again accommodate, this time creating a new schema about cats which he now knows are in a different group than dogs. This process continues throughout childhood as children learn and organize new information.

Behaviorism

Behaviorism is a theory based on the work of several researchers including John Watson, B.F. Skinner and Ivan Pavlov focus on children’s observable behaviors and actions. This theory indicates that children’s behaviors can be shaped through external cues called reinforcers.

Reinforcers are actions taken by adults to encourage or discourage certain behaviors. This process is called conditioning. When a child has been conditioned, their behavior has been shaped in response to the cues from the teacher to guide the child to the behaviors desired by the adult. An example of conditioning in a classroom might look like this: A teacher wants all children to sit down for circle time. She may announce that circle time is about to begin, and as each child sits, she gives a sticker to each one. The sticker acts as the reinforcement for desired behavior. After this process has been repeated over a few weeks, the children will come to sit as soon as the teacher announces circle time.

In recent years, there has been some criticism of behaviorism in classroom settings. Critics assert that reinforcements, like stickers, deter intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is a desire to do things based on one’s own wishes and goals. Many believe that children should engage in acceptable behavior simply because it is desirable and interesting. In practice, this means that to get children to sit for circle time, they must want to do it. How to make them want to do it? Make it interesting and fun! Sing engaging songs, smile, and use shakers and instruments to find a way to draw the children in.

A further criticism of behaviorism is that it does not help children learn acceptable behavior in the long term. That is, what happens when there is no sticker? In the absence of reinforcement, the desired behavior can diminish. What happens when children transition to a class where no reinforcers are given for sitting down?

Despite its shortcomings, behaviorism is still used in many classrooms and can be a successful method for guiding children’s behavior. Reinforcers can be seen as rewards for children and can contribute to higher class morale. Many teachers appreciate even the short-term effectiveness that behaviorism provides in guiding children toward acceptable behavior.

A final note on behaviorism: some teachers may be tempted to use snacks or treats as reinforcers. This practice is strongly discouraged, as it can interfere with healthy eating habits and raise issues for children who are experiencing food insecurity. Indeed, nothing edible should be used to direct children’s behavior.

Social Learning Theory

Image 3.3. Photo credit: lordmok on Pixabay is licensed under CC by 1.0

Social learning theory is based on the research of Albert Bandura about how children learn particular behaviors based on watching the actions of those around them. The individuals in a child’s environment are referred to as models. According to social learning theory, children observe the behaviors of others around them and use that as a model for their own behavior. For example, if a teacher commonly uses words like please and thank you with children, the children will begin to use those words as well.

Children usually model the important adults in their lives but may also model behavior from media sources. As such, social learning theory calls into question violent content seen in media because it may have an effect on child behavior. Social learning theory expands upon behaviorism in that children’s behaviors are not just a matter of behavior and reinforcement but are also interwoven with the social context as well. In this way, children learn about the consequences of actions in a more organic way rather than through prescribed reinforcers, leading to more long-term behaviors.

Consider an example of a toddler observing an adult opening a jar to find a hidden toy. The adult models the hand coordination involved in the action and expresses delight at the contents. This encourages similar attempts by the child who begins to practice the skill of opening a jar.

Sociocultural Development

Image 3.4. Photo credit: kasman on Pixabay is licensed under CC by 1.0

Sociocultural development theory addresses how children learn new skills through social interactions. It is related to cognitive developmental theory in that both are focused on how children think and learn. It was developed by the psychologist Lev Vygotsky.

Instead of focusing on how children interact with objects and concepts in the environment, social cognitive theory focuses on how children interact with other individuals in their environment. These individuals are referred to as the more knowledgeable other, as they have more skills and knowledge about a particular area than the child. The more knowledgeable other can be an older peer or an adult. According to social learning theory, when children are learning a new skill, they best accomplish it by operating on the upper edge of their abilities.

This is referred to as the zone of proximal development or ZPD. ZPD is the difference between what a child can do alone and what a child can do with help from a more knowledgeable other. For example, if 6-year-old Shruti cannot ride a bike alone but can ride it with help from her mother, then this activity is in her ZPD. How does her mother help her learn to ride? She might hold onto the back of the bike seat, steadying Shruti as she pedals. She may hold onto the handlebars, helping her daughter navigate turns. She may give verbal cues, alerting Shruti when she needs to apply the brakes. Whatever help Shruti’s mother gives is dependent on her daughter’s skill.

This is referred to as scaffolding. Scaffolding is the assistance given by the more knowledgeable other that changes in response to the child’s ability. The best way to support a child’s learning is to give them just the specific help that they need in order to allow them to complete the skill. If Shruti has no trouble balancing and steering, then holding onto the seat and handlebars will do her no good in learning. Verbal cues on when to apply the brakes are what she needs. On the other hand, if it is her first time on the bike, verbal cues on how to brake will not be very useful as she wobbles around and falls.

To engage in optimal learning, a child must be guided within their zone of proximal development. If a task is too easy, then then it may become boring. If it is too difficult, the child may become frustrated and give up. Through scaffolding, a more knowledgeable other can help support a child to learn things that they could not do alone. Then the more knowledge other will slowly reduce the support until the child can complete the task alone.

Psychosocial

Another theory that focuses on the development of the child as they move through stages is psychosocial theory. Developed by Erik Erikson, Psychosocial theory posits that human development is characterized by a series of stages. Each stage represents a transition time for learning and development and is marked by a specific aspect of development.

Beginning at birth and ending in late adulthood, this theory encompasses the lifespan. As an individual enters into each stage, they are faced with a psychological conflict, known as a life crisis. A life crisis is when two conflicting aspects of development must be navigated by an individual. The stages are listed in table 3.2. To illustrate how a child might move through a life crisis, consider the following example of the stage “initiative vs guilt”.

Three-year-old Leandro has used his crayons to color a lovely picture for his daddy and hangs it on the wall using tape. Daddy praises Leandro for his good idea to hang artwork on the wall using tape. Next time, Leandro decides to color directly on the wall, which leads to a scolding from Daddy instead. Leandro has shown initiative, taking independent action by hanging a picture on the wall all by himself. He also experiences guilt for his initiative gone wrong when he colors on the wall. As he moves through this process, he learns to take initiative in the appropriate way and gains pride from his accomplishments.

Age |

Life crisis |

|

0-18 months |

Trust vs. Mistrust |

|

18 months-3 years |

Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt |

|

3-5 years |

Initiative vs. Guilt |

|

5-13 years |

Industry vs. Inferiority |

|

13-21 years |

Identity vs. Confusion |

|

21-39 years |

Intimacy vs. Isolation |

|

40-65 years |

Generativity vs. Stagnation |

|

65 years and beyond |

Integrity vs. Despair |

Table 3.2

Attachment Theory

Image 3.5. Photo credit: balouriarajesh on Pixabay is licensed under CC by 1.0

Attachment theory was developed on the premise that infants need physical and emotional support from a primary caregiver early in life in order to become emotionally well-adjusted in early childhood and beyond. Developed by Mary Ainsworth and John Bowlby, this theory is grounded in the mother-child bond but can be applied to the father or other primary caregiver.

Attachment theory proposes four different types of bonds or attachment patterns, that a child can have with the mother (or primary caregiver). An attachment pattern is a description of the relationship between mother and child based on the behavior of the child. Attachment patterns were measured using a lab test called the “Strange Situation”. In the Strange Situation, the mother and baby played in a playroom along with a friendly stranger. The mother leaves for a brief time, leaving the child to play with the stranger. When the mother returns, the baby’s behavior upon this “reunion” is observed and coded as a type of attachment pattern. There are four main types of attachment patterns which are outlined in table 3.3.

Attachment pattern |

Child’s behavior upon reunion |

Caregiver’s responsiveness to child’s needs |

|

Secure |

Seeks proximity to caregiver; positive response; is calmed by caregiver’s attempts to soothe |

Sensitive to child’s needs; consistent |

|

Insecure avoidant |

Does not seek proximity to caregiver; does not seem distressed at caregiver’s absence |

Not sensitive to child’s needs; distant |

|

Insecure resistant |

Is not calmed by caregiver’s attempts to soothe; resists proximity |

Inconsistent in response to child’s needs; sometimes sensitive, sometimes distant |

|

Insecure disorganized |

Does not fall into a reliable attachment pattern |

Emotionally distant |

Table 3.3

There has been some recognition in recent years as to the lack of cross-cultural validity of the strange situation as a measure of attachment, meaning attachment might not look the same for everyone. The strange situation was developed using a mostly Western, middle-class sample. Because adult interactions with infants can vary by culture, the reactions of infants during the strange situation might not always look the same. While there are some other ways to measure attachment, more research is needed to uncover ways to measure attachment across a variety of cultures.

Secure attachment leads to positive outcomes for children. Securely attached children are more likely to have positive social relationships and are more successful in school. On the other hand, insecurely attached children have trouble forming and maintaining social relationships and tend to have behavior and academic problems in school.

What do mothers and other primary caregivers do to form a secure attachment? It mostly relies on sensitivity. Sensitivity in this sense refers to a responsiveness to an infant’s emotions. If the baby cries, the mother soothes her. If the baby laughs, the mother laughs along. In this way, the infant builds a reliable bond with the mother that sets them up for a stable emotional connection. Additionally, it helps a child develop an internal working model for how relationships should function in general.

An internal working model is a conceptual understanding of how the relationship between an individual and a loved one should be. With a securely attached child, their internal working model might be something like “the adults in my life are people who love me and take care of me. My needs are met by them”. This is later transferred to form trusting relationships with others like grandparents, teachers, and later, romantic partners.

Ecological Systems Theory

Ecological systems theory, developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner, focuses on the child in the context of their environment. The premise of this theory is that the child develops in response to the multiple systems that influence them. For example, a child is influenced by their immediate household family, extended family, neighbors, schools, and society at large.

These systems are organized into categories based on their immediate contact with the child and how directly or indirectly they influence the child. The systems also influence one another. For example, the language a family speaks at home is influenced by the society in which the family live.

- Microsystem: The child’s immediate environment (family, school, peers)

- Mesosystem: Interactions between microsystems (e.g., parent-teacher relationships)

- Exosystem: Indirect influences on the child (e.g., parent’s workplace, community resources)

- Macrosystem: Cultural values, beliefs, and norms

- Chronosystem: Changes over time in the child and their environment

Let us take a look at an example of 3-year-old Maria. She lives with her parents and older sister and they speak Spanish at home. Her parents emigrated from Mexico to the United States seven years ago.

- Her microsystem includes her mother, father, sister, her best friend Lucia, and the childcare they attend at the local community center.

- Her mesosystem is when her parents volunteer at the community center where her childcare center is and when she has a playdate at Lucia’s house.

- Her exosystem includes the marketing firm where her parents work, the healthcare provided by the parents’ employers, and the state funding that runs her community-based childcare center.

- Her macrosystem contains the attitudes of society about her family’s native language and her parent’s immigration status.

- Her chronosystem reflects the changing status of women of color – as Maria has more and more role models in the media who represent her culture.

As this example illustrates, the ecological systems model represents the dynamic environments that shape how a child develops. It is not just the parents, extended family, peers, or teachers, but rather all the parts of society working together. This theory emphasizes the interconnectedness of these systems and the importance of considering the broader context in which a child develops.

Reflection

What are some ways in which you could use child development theories in your work with children?

Final Thoughts

The field of early childhood education and the profession of working with young children is a rewarding career with a rich history of teaching, nurturing, and caring for young children. As teachers, our skills, knowledge as well as personal beliefs and morality shape how we interact with children and families.

Our field is one with historical roots that tie to modern-day concepts that is supported both within our state and nationally through efforts to professionalize the field.

One thing is certain: change is all around us in the field, and the profession must respond to the trends. This means we will always strive to do what is best for the children and families we serve and continue to move with the wave of change.

References

Bipartison Policy Center, (2019). History of Federal Funding for Child Care and Early Learning. Retrieved from www.bipartisanpolicy.org

Cahan, Emily. (1989). Past Caring, A History of U.S. Preschool Care and Education for the Poor, 1820-1965.

Coalition for Responsible Home Education, 2020. https//www.responsiblehomeschooling.org

Elkind, David (2010). The History of Early Childhood Education. Retrieved from http://communityplaythings/resources.

Kiesling, Linda (2019). Paid Child Care for Working Mothers? All it Took Was a World War, New York Times.

Michel, S. (2011). The History of Childcare in the U.S. Social Welfare History Project. Retrieved from http://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/programs/child-care-the-american-history/

Miller, E. and Almon, J (2009). Crisis In Kindergarten, Why Children Need to Play in School. Retrieved from http://allianceforchildhood.org

NAEYC (March, 2020). Power to the Profession: http://powertotheprofession.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Power-to-Profession-Framework-exec-summary-03082020.pdf

Obama, Barack (2013). Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives,gov/the-press-office/2013

QRIS National Learning Network https://qrisnetwork.org

UNICEF (July, 2019). A No-Brainer: Advocating for Early Childhood Education. www.unicefusa.org

Yarrow, Andrew. (2009). History of U.S. Children’s Policy, 1900-Present.

Websites you may want to explore further

National Association for the Education of Young Children: www.naeyc.org

NAEYC Equity Statement: https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity

Unifying the Framework Executive Summary: http://powertotheprofession.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Power-to-Profession-Framework-exec-summary-03082020.pdf