3 Understanding Child Development

Authored by Angela Blums, Reviewed by Sally Holloway, Edited by Jean Doolittle Barresi

Image 5.1 Bubbles is licensed under CC by 1.0

Key Points from this chapter:

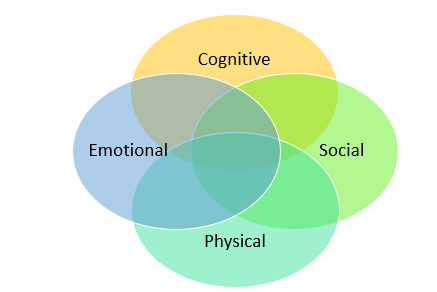

- Young children’s development can be conceptualized in four main areas: physical, intellectual, emotional, and social.

- Understanding how children develop is important to ensure healthy developmental progression.

- While there are many commonalities, there are also individual and cultural differences in development such that development is not identical for each child.

Terminology Found Throughout This Chapter:

Atypical development: When a child does not develop in the way that is congruent with averages for a given age, causing a disturbance to everyday activities.

Child development: The pattern of change that begins at conception and continues through adolescence.

Culturally relevant pedagogy: The practice of including ideas and artifacts that refer to a child’s individual culture.

Developmentally appropriate practice: Methods that promote each child’s optimal development and learning through a strengths-based, play-based approach to joyful, engaged learning.

Developmental domains: Specific areas in which growth occurs – Physical, Cognitive, Emotional, and Social.

Differentiation: The thoughtful practice of tailoring activities to meet children’s individual needs.

Early childhood period: Ages birth through age eight.

Executive function: Collection of processes that encompass attention, working memory, and inhibition.

Fine motor skills: Movement related to small muscle groups in the body.

Gross motor skills: Movement related to the large muscle groups in the body.

Joint attention: The action of a child and a caregiver focusing on the same object or concept at the same time.

Metacognition: Self-reflection; an ability to think about one’s own thoughts.

Open-ended questions: Questions that do not have a yes or no answer.

Separation anxiety: A fear of being separated from their primary caregiver.

Temperament: An infant’s regular way of reacting with their environment.

Toxic stress: Physical or emotional abuse, neglect, witnessing of physical or emotional abuse of another person, or extreme poverty.

Typical development: When a child develops in a way that is congruent with averages for a given age.

Image 5.2 Andreas is licensed under CC by 1.0

Image 5.2 Andreas is licensed under CC by 1.0

3.1 Child Development

Child development is the study of how children grow, learn, and change over time. It encompasses the physical, cognitive, social, and emotional changes that occur from conception through adolescence. Understanding child development is essential for early childhood educators, as it provides a foundation for creating developmentally appropriate learning experiences and environments that support children’s overall well-being and growth.

This chapter will explore the four main developmental domains:

- Physical development

- Cognitive development

- Social development

- Emotional development

By gaining a deeper understanding of these domains and how they interact, early childhood educators can better support children’s learning and development.

Role of Environment on Development

The way that children are cared for impacts how they develop. An environment filled with loving, responsive caregivers works wonders on a child’s physical, cognitive, social, and emotional development. Conversely, an environment filled with toxic stress will slow down the healthy development of children and those adults caring for them. Signs of toxic stress include physical or emotional abuse, neglect, or witnessing of physical or emotional abuse of another person. Toxic stress, sometimes referred to as childhood trauma, can be detrimental to the early childhood stage of development. It can also impact social, emotional, and cognitive development, lower academic achievement, and lead to long-term health-related issues such as cardiovascular problems. It is important to create an environment for the child that includes safe, sensitive, and supportive care.

Reflection

What things can a caregiver do to help a young child feel safe and secure?

3.2 Developmental Domains

Image 5.3. Text reads: Physical, cognitive, social, and emotional.

Physical Development

Physical development involves changes in children’s bodies, including growth, motor skill development, and brain development.

Brain Development

Brain development is an important part of physical development. Brain development begins in utero and continues rapidly during the first few years of life. During this critical period, infants require responsive interactions with caregivers, a safe and secure environment, and proper nutrition to support healthy brain development.

Because of this, it is important to support fetal brain development through proper nutrition and care of the mother. Once born, infant brains develop rapidly. Brain connections, called synapses, develop rapidly during the first few months to the first 3 years of life, making this period critical for healthy brain development.

During infancy, babies require responsive interactions with trusted caregivers that include verbal, expressive, face-to-face engagement. Additionally, and above all, they require a safe and secure home environment for healthy brain development.

Motor Skills

Image 5.4 Gross Motor Skills is licensed under CC by 1.0

Image 5.4 Gross Motor Skills is licensed under CC by 1.0

Children’s bodies are designed to wiggle and move. Motor skills refer to a child’s ability to move and coordinate motion using their bodies.

Motor skills are divided into two categories:

- Gross motor skills: These involve the large muscle groups and include activities such as walking, running, climbing, and jumping.

- Fine motor skills: These involve the small muscle groups and include activities such as grasping objects, drawing, and buttoning clothes.

In order for gross motor skills to develop successfully, infants and children must be given opportunities to move their bodies freely, safely, and without restriction, starting from birth. This is why most pediatric physical therapists recommend against the use of so-called “baby containers” – chairs, bouncy seats, swings, and jumpers that place an infant in an upright position before their body is ready to do so on its own. These devices can hinder development. Instead, babies should play on a blanket or mat and have a few minutes of “tummy time” each day starting at birth. This helps to strengthen neck and shoulder muscles that will later be used in crawling. As children begin to crawl and walk, soft climbers can help to develop gross motor skills.

Once solid on their feet, children need opportunities to practice running, jumping, balancing, and climbing. This is why daily outdoor play is vital. Playgrounds can be great places for children to experiment with gross motor skills. Outdoor play in natural areas is also important. Consider the difference between climbing stairs or monkey bars on a playground vs climbing the branches of a strong, low, tree. Both offer opportunities for using arms and legs, but tree climbing allows children to use muscle groups in new positions and learn to balance in an irregular position. If no safe climbing trees are available, learning to walk or run on uneven ground in a field or meadow can also be beneficial. It is important for children to move their bodies in many different ways.

Playing outdoors on playgrounds and in nature provides children with opportunities to take risks. When children climb, they not only build muscle and coordination but also learn to overcome fears. This can lead to greater self-confidence that carries over into other areas as well. This is one way in which outdoor activity supports not only physical but also emotional development.

Fine motor skills begin to develop in infancy when the child first learns to grasp a toy such as a rattle or a cloth. Later, they learn to throw a ball, hold a crayon, and use scissors. Children can be given opportunities to use their hands in a variety of ways using age-appropriate materials. Young children love to practice fine motor skills using real-life items, such as bucking the clasp of a highchair strap or zipping a zipper. This has the added benefit of fostering independence which supports emotional development. Children can coordinate their finger movements while learning a zipper and they can also feel proud when they can zip their own jacket to go outside. Opportunities for fine motor development are everywhere and can be as simple as picking up a leaf and ripping it into tiny pieces. Teachers can foster fine motor skills by making sure to create challenging activities based on each child’s developmental level.

3.3Cognitive Development

Image 5.5 Reading Together is licensed under CC by 1.0

Cognitive development includes all things related to thinking and learning. In the early childhood stage, the focus is on problem-solving, memory, and language acquisition.

Executive Function

One key area of cognitive development is called executive function. Executive function is the collection of processes that encompasses attention, working memory, and inhibition, and it develops between the ages of about 3 and 6 years.

- Attention is the ability of a child to focus on something, like carefully concentrating on a picture in a book.

- Working memory refers to the ability of a child to maintain several pieces of information in the mind for a short period of time. This could be recalling some items present in the picture in the book, like a tree, a bird, and a house.

- Inhibition is the ability to block out distractions, such as other background designs on the book or even the sounds of other children playing in the classroom.

Development of executive function is key to building social relationships, acquiring, and maintaining learning, and eventual academic success. For example, if a child is going to learn how to add using blocks, she might have to first pay attention to the blocks in front of her, remember that she had three blocks on one side and one block on the other side, and inhibit the distraction of other toys on the table.

All of these components come together with executive function. It is important to remember that because executive function is developing between the ages of about 3 and 5 years, young children do not have the ability to pay attention to things for long periods of time. Nor do they have the ability to remember multiple pieces of information or block out distractions. This is important when planning activities for young children.

Setting the expectation that young children should sit at a table and focus on one activity will result in frustration of both children and teachers, as children will communicate their lack of executive function with a lot of wiggles and movement! This is healthy, and teachers should keep this in mind when planning activities that require concentration.

Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) need extra support to develop executive function, as concentration and inhibition are particularly difficult. Children who are in chaotic environments or those who have experienced toxic stress and trauma may struggle with the development of healthy executive function.

Strategies that have been successful in promoting executive function are games and activities that practice concentration and task-switching. Such games need to be fun, not tied to punishment or reward. Deep breathing and meditation have also been shown to aid in the development of executive function for children who are struggling.

Problem-Solving

Teacher: “It looks like your block tower is falling down a lot. I wonder why?”

Child “Because the carpet is bumpy and soft”

Teacher: “How can you make a more stable base for your tower?”

Child: “I could put a tray underneath it!”

Teacher: “Want to try that and see what happens?”

When children encounter a challenge, they learn to practice problem-solving. Problem solving involves assessing the problem, devising a plan, carrying out the plan, and reflecting on the outcome. Children may do this without actively knowing that they are carrying out these four steps. For instance, if a child is building a block tower on a soft carpet, it might be unstable and fall down. The child might think of a solution: get a tray or a large book to set on the carpet to create a flat surface. The child then gets the tray, builds the block tower, and then checks to see if it is wobbly or stable. Problem solved!

Children solve many such problems each day during play. It is helpful for teachers to facilitate problem-solving by asking open-ended questions, or questions that do not have a yes or no answer. This type of question helps the child see the main features and problems in the situation, encourages thinking about solutions, and suggests solutions, all without giving the answer. An exchange might look like the following:

This exchange of open-ended questions helps the child learn to problem solve on their own. The use of the phrase “see what happens” encourages the child to engage in the fourth step of problem-solving, assessing the outcome. After all, a problem-solving strategy may not succeed, and the child might have to try something else. This is all part of the process of learning.

Theory of Mind

Educators can support theory of mind by discussing characters’ feelings and motivations during story time and encouraging children to consider others’ perspectives during play.

As young as 2 ½ healthy children start to figure out how other people are thinking and feeling. The study of this ability is referred to as theory of mind. Theory of mind is the ability to understand that others have thoughts, beliefs, and perspectives that may differ from one’s own. This skill develops during the preschool years and is crucial for social interactions and empathy. One of the hallmarks of the theory of mind is the ability to pick up cues and understand the mental states of others.

It is difficult for a young child to get out of their own head. Children see things from their own perspective and have a difficult time understanding the perspectives of others. So, if a child is happily playing and sees another child crying, it takes some time before they can understand that what they are thinking and feeling is not the same as what others are thinking and feeling.

It is clear to see the connection between this cognitive ability and building social relationships. Children with Autism have difficulty with theory of mind, and many children with Autism do not develop it at all. For this reason, Autism interventions include instruction on how to read the mental states of others.

Self-reflection

Self-reflection is the ability to think about one’s own thoughts. This is sometimes referred to as metacognition, which develops between middle childhood and adolescence. However, during early childhood, there are signs of self-reflection, or thinking back on one’s thoughts.

Self-reflection is helpful in problem-solving and emotional development. If a child has solved a problem such as mixing the colors just right for a painting, the teacher might ask “Why did you decide to do it this way?” or “Tell me about why you chose to mix those colors?”. This helps children to think through their process and helps them remember the strategy for next time.

Early childhood educators can lay the foundation by asking children to explain their thinking and encouraging them to reflect on their experiences.

Language

Language development is a critical aspect of cognitive development. Children learn to understand language in infancy through responsive interactions with adults. Adults should speak with and listen to infants starting at birth, making eye contact and using a gentle tone. When infants begin to babble, adults can take turns talking and letting the baby babble. This sets up the format for later turn-taking in conversation.

Throughout childhood, children will usually understand more words than they can speak. As children begin to understand language, they can answer simple questions with a yes or no response by shaking their heads or using simple sign language. It has become a common practice to teach hearing infants a few common signs to facilitate communication earlier than when they begin speaking. Infants with hearing impairments can be taught sign language as soon as challenges are detected.

Books should be read and stories told to children starting in infancy, as this helps develop new vocabulary and creates a connection to literature that will later be important for learning. It also helps strengthen the relationship between the child and the adult.

Joint attention is the action of a child and a caregiver focusing on the same object or concept at the same time. This shared experience helps to form a new vocabulary. Children learn new words much more quickly and efficiently with joint attention than they ever could by viewing a video. In fact, there is evidence that suggests that television can actually hinder language development rather than help. Here is an example of joint attention in action.

Setting: Teacher Tanisha and 18-month-old Sofia are looking out the window. Teacher Tanisha sees some autumn leaves falling from the tree. Teacher Tanisha: “Look Sofia, leaves are falling from the tree.” [Sofia looks at the leaves][Teacher Tanisha and Sofia look at each other and make eye contact]Sofia: Smiles and says “leaves!” This action has three steps: adult and child focus on the same object, adult and child make eye contact, adult names the object. In this way, children add many new words to their vocabulary, the words are presented in a real-life context, and they strengthen social relationships with their caregivers.

Once children begin to speak, language use should be encouraged through open-ended questions and topics that interest the child. Songs, rhymes, and books are all effective and fun ways to encourage language, but everyday conversation is also helpful. Children like to be involved in the real-life daily activities of adults, so engaging a child while doing tasks around the classroom is a good way to support language. Mealtimes are another opportunity for language development, as eye contact is easy while sitting at a table.

When learning to speak, children will inevitably make errors with grammar and syntax. The best way to support language development is to model the correct grammar and word order rather than correcting the child. This avoids the embarrassment that might come with being called out on making a mistake, and language modeling is simply a better way for the brain to remember how to use grammar. An exchange might look something like this:

Child: “After breakfast, I goed outside.”

Teacher: “After breakfast, you went outside? How fun! What did you do outside?”

Child: “I played with Weihua out there”

By using language modeling, the teacher provides an example of when and how to use the word in a certain situation, thus helping the child remember it for the next time.

Image 5.6 Playing in Water is licensed under CC by 1.0

3.4Social Development

Social development includes all things related to interacting with others. Parents, family, teachers, and peers all have special relationships with children, and those relationships are also related to one another. Teachers form relationships with parents, which benefits the child, and adults can facilitate communication between children. At the center of this is the child, who is driven to form relationships with adults and children alike.

Relationships with Caregivers

Infants begin to form relationships with caregivers at birth. Forming a strong relationship with a primary caregiver gives a baby a feeling of safety and security. The primary caregiver is typically the mother, but can also be the father, relative or other main person in the infant’s life. Eventually, infants form relationships with secondary caregivers like relatives and teachers.

Healthy relationships are characterized by things like reciprocal interactions, sensitivity to emotions, a warm, calm, voice, and lots of positive language. These are good ways to interact with children of all ages but are particularly important with infants as toddlers. Children may form preferences to particular caregivers and be upset when one is not available.

Similarly, children around from about 9 to 18 months of age may go through separation anxiety or a fear of being separated from their primary caregiver. This is normal, and children’s emotions should be respected during this time. They do not understand that their mother will return later, which can be upsetting.

Teachers can provide support by recognizing the child’s emotions and providing physical comfort (if the child wants it). Using phrases like “I see you are sad that mommy has left” and “You are feeling upset right now” are helpful in supporting the child through the tough time.

Temperament

Temperament is a developmental characteristic that intersects social, emotional, and physical development, and because it has genetic underpinnings, it is thought to be “inborn”. When most people think of genetics, they think of physical traits such as eye color or hair texture. While these are genetically inherited characteristics, genetics are also involved in a child’s disposition, which can later become a key part of their personality.

Temperament is an infant’s regular way of reacting to their environment and is categorized as either easy, difficult, or slow to warm up. This is measured by several factors including smiling and laughter; regularity in eating and sleep habits; approach or withdrawal; adaptability to new situations; intensity of responsiveness; general cheerfulness or unpleasantness; distractibility or persistence, and soothability.

Parents of multiple children often report how their first child’s temperament differed from their second: “Jorge was so quiet and peaceful as a baby. He slept all day and never cried! Carlo on the other hand, fussed and cried all day. We thought he might never grow out of it!” It is important to know that babies of all temperaments can grow up to be happy, healthy, and balanced individuals.

Children’s temperament does indeed impact their behavior as an infant and this is a good example of how children’s genetic disposition can interact with their environment to help them develop. This is also an example of how different developmental domains can overlap. What is biological can also be social and emotional. The relationship between a child’s temperament and a caregiver’s personality is sometimes referred to goodness of fit. If an infant has a difficult temperament, she may have frequent periods of intense crying, be difficult to soothe, and may not fall asleep easily. If she has a primary caregiver who is ready for a challenge and sees this baby as an individual who needs love and understanding, then they have a good “goodness of fit”. On the other hand, if an infant has an easy temperament and a caregiver who does not share her sunny disposition, they may not have a “goodness of fit”.

That is why it is important for caregivers of multiple children to be adaptable to multiple infant temperaments. Each child is an individual, and no child is better or worse than another. Further, there is no perfect temperament. Children are who they are, and it is up to the important adults in their lives to respect that and treat all children with love and care.

Relationships with Peers

As children grow and mature, they begin to show interest in other children. At first, it may be just a 10-month-old watching other children playing on a playground. This may not seem like much but observing older children at play lays the groundwork for later social interactions. Later, children will play with toys alongside one another, but not yet interact. Adults may be eager for children to form friendships with others, but this time of play is important for children to experience before they move into play involving rules and negotiation.

A great deal of peer relationship building is in the context of play. Play is, after all, the work of childhood, and this is what children spend most of their waking time doing. During play, children learn the rules of games, how to read a peer’s emotions, and how to engage in social problem-solving. If a group of 5-year-old children are playing a game of hide and seek, younger children who are new to the game will quickly learn the rules from the others. If two children are playing with crayons and one takes the crayon from the other, the ensuing frustration will be evident. In this way, children learn to read the emotions of peers.

Perhaps the most interesting development is social problem-solving. When children encounter a conflict, it can disrupt their play, and if there is one thing, we know to be true about children, it is that they do not care for their play to be interrupted. This motivates both children to solve the conflict as quickly as possible in order to continue play.

Take an example of two children playing in the kitchen dramatic play area. Both children want to cook, but there are only enough materials for one to stir the soup. A conflict arises, and in order to navigate this, the children decide that one will stir the soup and the other will chop the vegetables. This is an example of sophisticated negotiations and problem-solving. Both children need to regulate their emotions, come up with alternative activities, and decide who will do which activity. If they give up at any time during the process, then the game is over.

This type of problem-solving behavior in the context of play is highly complex and takes a lot of practice. Teachers can facilitate this by stepping in to help regulate emotions, brainstorm alternative activities, or help decide who will do which activity, but only if it seems that the children need help.

Image 5.7 Playing Together is licensed under CC by 1.0

3.5Emotional Development

Emotional development includes the development of emotions, emotion regulation, and a sense of self. Emotional development is closely related to social development. They are so closely related, in fact, that some frameworks of child development refer to them as socioemotional development or social-emotional development. In this section, we will discuss some main areas of development that lean more toward the emotional side of things.

The Development of Emotions

When babies are born, they experience basic emotions such as contentment, interest, and distress. After a few months, they begin to experience fear, anger, happiness, and surprise. Later, when a sense of self develops, more emotions come along such as guilt, pride, and embarrassment. It is important for caregivers to allow children to express emotions freely and teach them to express them in socially appropriate ways.

One good way to do this is through modeling. Teachers can express mild frustration and model strategies to overcome it. For example, a teacher may demonstrate frustration with difficulty opening a jar, and then take some deep breaths before asking another teacher for help. This is an effective way to teach children how to manage emotions.

Another way is to read books that depict children overcoming difficult emotions so that children have a benchmark that they can relate to. Yet another approach is to encourage the expression of emotions through dance and art. Children may also act out emotions through pretend play. Providing children space and time to work through feelings in a pretend setting can be very helpful for the development of emotions.

Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation refers to a child’s ability to control or modify one’s own emotions. It is closely tied to brain development. The underpinnings for emotion regulation begin in infancy with the infant’s primary caregiver. When a baby cries for attention and is soothed by the caregiver, it sends signals to the brain which help it to calm down. With this repeated action of crying and receiving comfort from a caregiver, the baby’s brain slowly learns the process of how to regulate emotions. This process takes a very long time, and more sophisticated emotion regulation occurs alongside executive function. This means that between the ages of 3 and 5 years, children are able to shake off frustrations in a socially acceptable way.

Children with ADHD can have persistent difficulty with emotion regulation, making it hard to succeed in school environments designed for typically developing children. These children need special support and understanding in order to work toward developing emotional coping strategies.

3.6 Typical and Atypical Development

Image 5.8 Drinking Juice is is licensed under CC by 1.0

Most children develop in a similar way. Even when cultural backgrounds, geographic locations, and personal characteristics vary, child development is generalizable. That does not mean, however, that all children are the same. Some children develop more quickly in cognitive areas, but more slowly in social areas. Some children develop more quickly in general than others, some more slowly.

Children are living, breathing beings, and some variation is normal. When a child develops in the way that we expect, we refer to this as typical development. There is room for a good deal of variance in typical development. For instance, babies can speak their first words anywhere from 9 to 13 months, and children can write their own names anywhere from 3 to 5 years. This variance is healthy and normal.

Some variance is unusual, and that is referred to as atypical development. Atypical development can slow down growth in other areas of a child’s life. If a child cannot speak any words by 15 or 16 months, it is considered atypical development. The ways and speed in which children grow is measured by tools called developmental assessments.

The caring adults in a child’s life benefit from knowing how the child is developing, where they are struggling, and what to expect next. Despite the name, developmental assessments are not complicated standardized tests that a child must complete. Instead, they are carried out by the teacher through observing the child at play or by playing small games and activities with the child. The teacher records the child’s developmental milestones on the assessment and later shares it with the parents.

If development is not on track, teachers should speak with parents and connect them with specialists who can help. Specialists will administer another type of assessment that is specially designed to diagnose developmental disabilities. Atypically developing children benefit from early intervention programs that can help them get back on track.

Reflection

- What are some activities that you could create to support child development?

- On which developmental domains will your activities focus?

3.7 Supporting Child Development in Early Childhood Education

Understanding child development is essential for providing high-quality early childhood education. Educators can support children’s development by:

- Creating a safe and nurturing environment that promotes exploration and learning

- Providing developmentally appropriate materials and activities that challenge and engage children

- Responding to children’s individual needs and interests

- Fostering positive relationships with children and their families

- Engaging in ongoing professional development to stay informed about best practices in early childhood education

Final Thoughts

Child development is a complex and multifaceted process that encompasses physical, cognitive, social, and emotional growth. By understanding the key aspects of each developmental domain and how they interrelate, early childhood educators can create learning environments and experiences that support children’s holistic development.

As educators, it is essential to recognize that each child is unique and may develop at their own pace. By remaining attuned to children’s individual needs, providing appropriate support and guidance, and collaborating with families and specialists when necessary, educators can help all children reach their full potential.

References

Adolph, K. E., & Robinson, S. R. (2015). Motor development, vol. 2: Cognitive processes. Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Sciences, DOI: 10.1002/9781118963418 .childpsy204

Allen, G., et al. (2011). Functional neuroanatomy of the cerebellum. In A. S. Davis (Ed.), Handbook of pediatric neuropsychology (pp. 147–160). New York, NY: Springer.

Bebko, J. M., McMorris, C. A., Metcalfe, A., Ricciuti, C., & Goldstein, G. (2014). Language proficiency and metacognition as predictors of spontaneous rehearsal in children. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 68(1), 46–58

Bird, A., Reese, E., & Tripp, G. (2006). Parent–child talk about past emotional events: Associations with child temperament and goodness-of-fit. Journal of Cognition and Development, 7(2), 189–210.

Developmentally Appropriate Practice (2020). National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents

Haywood, K. M., & Getchell, N. (2014). Life span motor development (6th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Lecce, S., Demicheli, P., Zocchi, A., & Palladino, P. (2015). The origins of children’s metamemory: The role of theory of mind. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 131, 56–72.

Thompson, R. A., & Meyer, S. (2007). Socialization of emotion regulation in the family. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 249–268). New York, NY: Guilford.

Zelazo, P. D., & Müller, U. (2010) Executive function in typical and atypical development. In U. Goswami (Ed.), The Wiley- Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development (2nd ed., pp. 574–603). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781444325485.ch22

Websites you may want to explore further

Developmental milestones resource: https://www.dcyf.wa.gov/sites/default/files/pubs/EL_0015.pdf

Developmentally Appropriate Practice Position Statement from the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC): https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents

Professional Standards and Competencies for Early Childhood Educators (NAEYC): https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/professional-standards-competencies

Talking with parents about child development: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/pdf/parents_pdfs/tipstalkingparents.pdf

Developmental screening: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/screening.html

Center for Disease Control Milestones Checklist: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/pdf/checklists/Checklists-with-Tips_Reader_508.pdf