19

Basak Tanulku, Independent Consultant, Turkey

In the last couple of decades, cities all over the world have become segregated into an endless patchwork of shopping malls and multi-purpose complexes leading to a neo-medieval age. Gated communities are an important part of this urban process, founded against the general norm of open urban space and mixed urban culture. They receive significant attention in academic circles especially in the fields of human geography, planning, and housing. The growing attention to the analysis of gated communities has created a literature consisting of different research perspectives and different contexts of investigation and consequently, diverse definitions. A definition, stripped from any socio-cultural and historical context comes from Roitman: gated communities usually refer to various types of residential and/or office complexes closed to outsiders by different mechanisms such as walls, gates, and fences and protected against potential dangers by security guards and CCTV cameras. Gated communities are composed of spatial (walls and gates), social (population characteristics) and legal mechanisms (rules of conduct managing life inside these spaces) (Roitman, 2010).

A Common Urban Form

Gated communities are not the first developments characterised by walls, fences and an exclusive lifestyle closed to the rest of society. Rather, there were similar forms of gating seen in different parts of the world reflecting a common trend especially among the upper classes wishing to retreat from the masses (Blakely & Snyder, 1997; Low, 2003; Sassen, 2012). Similarly, contemporary gated communities are usually interpreted as an upper class desire for status, community life, belonging, and security within a neoliberal urban context, which have become more popular since the late 1970s and early 1980s.

However, as discussed in the book edited by Bagaeen and Uduku (2012), gated communities do not have the same meaning for all. Rather, the authors demonstrate differences in terms of the factors underpinning their development, their impacts on wider urban realms and meanings across societies. For example, in developed countries such as New Zealand, gated communities mostly reflect a search for a lifestyle, and/or way to share and reduce the costs of common amenities leading to more sustainable lifestyles (Dupuis & Dixon, 2012). Instead, particularly in developing countries, gated communities reflect larger socio-economic issues and concerns about increasing crime levels. For example, in the Latin American context, gated communities are seen to increase socio-spatial fragmentation, inequality, urban sprawl, and environmental degradation (Roitman & Giglio, 2012). In China (Tomba, 2012) and the Middle East (Bagaeen, 2012), gated communities reflect a wish to return to a more traditional way of life. The literature also demonstrates that in the developing world, gated communities also reflect the wish to imitate Western way of life and are regarded as status symbols within those contexts (Suarez Carrasquillo, 2011; Webster, Glasze, & Frantz, 2002; Wu, 2010).

Turkey and Neoliberal Urbanisation

Turkey has experienced significant economic and socio-political change since the 1980s, which contributed to the emergence of gated communities. The implementation of neoliberal economic policies transformed urban land into a source of profit and a new housing market emerged dominated by large developer companies (Oncu, 1988). The emergence of new forms of capital accumulation also led to a new and more polarised class structure characterised by the new middle and/or upper-middle classes in search of new lifestyles of status, belonging, and community (Genis, 2007). However, gated communities are not caused by economic factors alone, but also by the symbolic ones such as people’s perception of the cities they live in and/or the people who share their urban spaces. As discussed by Oncu (1997), large cities, especially Istanbul acquired a negative meaning for the new middle and upper classes due to the mixed urban culture characterised by tensions in public spaces between established inhabitants and migrants, the erosion of a common culture as well as increasing crime rates. Relatedly, cities became associated with environmental degradation due to increased pollution, higher densities, declining green space, decaying urban infrastructure, and lower levels of general living quality. The changing meanings of cities created a wish to live in a detached house, often a house far from city centres, which became a status symbol for upper classes (Oncu, 1997).

Istanbul: A city of more than 8,500 years. The spectacular Hagia Sophia in the historic peninsula mixes with high-rise business and residential towers being erected all over the city. [1]

Istanbul: The Global City of Turkey

Istanbul is the first city experiencing this process stronger than any other Turkish city, as the result of its particular features: Istanbul has a history of approximately 8,500 years spanning over pre-Christian, Christian and Islamic cultures. It was the capital city of Byzantium and Ottoman Empires. It is the most populated city of Turkey with a population of more than 14 million and it has the highest density among other cities in the country [2]. As a result, Istanbul attracts most of the foreign investment and visitors, hosting various international festivals, and is the most important centre of secondary and higher education of Turkey. Istanbul also contains two financial centres on each side of the city, comprising an important white-collar population working in the finance, insurance and real estate sectors. Starting from the 1980s, local political actors projected Istanbul as a global city (Keyder, 2000). For political actors, together with its rich heritage, diverse population, various cultural events and touristic attractions Istanbul was the perfect global city of Turkey which would generate profit through various real estate investments. Broadly speaking, currently, Istanbul is under massive transformation through two ways: first, mega-development projects in outer zones which also involve alteration of the landscape and second, urban regeneration and gentrification projects which are about demolish and/or renovate old inner city neighbourhoods (Tanulku, 2013b).

A Counter-Urban Phenomenon

In Istanbul the primary developments which can be regarded as the first gated communities are to be found close to the city centre. However, gated communities in this piece are associated with a counter-urban process accelerated after the 1980s, when Istanbul’s natural beauties, such as the world-known Bosporus, and the outer zones relatively intact from construction started to be sold to developer companies. The opening of these lands to construction was related to the transformation of housing market through the introduction of large developer companies into domestic market, as well as gradual removal of urban planning, once the guarantee of the protection of urban heritage and resources. In addition, Istanbul’s proximity to the North Anatolian Fault Line and low quality housing make it vulnerable to strong earthquakes, seen in the 1999 Marmara Earthquake. This was a turning point for many changes, including the acceptance of new construction regulations to provide better housing quality and the rise of a desire to live far from the city centre (Tanulku, 2012a). These intact areas became full of gated communities and related facilities, including shopping malls, café and restaurant chains and private schools and universities.

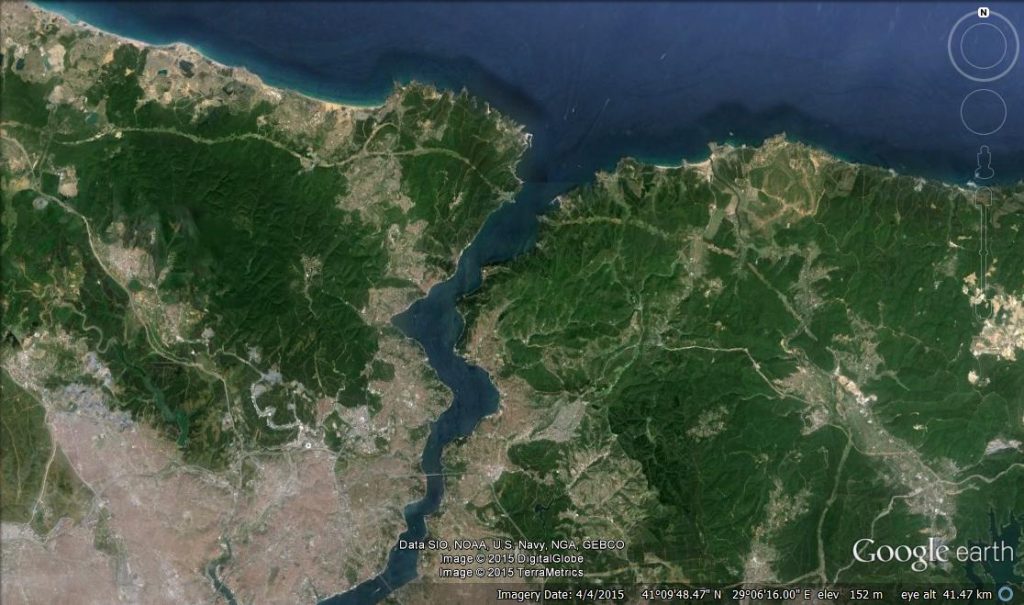

Istanbul from Google Earth: the north of the city covered with native forests faces with the threat of destruction due to the construction of new developments, such as gated communities, private universities and business and shopping facilities. Gated communities are located in all parts of the city, especially the outer zones.

Gated communities are regarded to provide community and belonging due to culturally-similar neighbours, good-quality homes built by prominent developer companies and designed by well-known architects and various amenities reducing the need of using public services. While the primary examples of gated communities in Istanbul reflect an elitist secession from city centres, since the beginning of the 2000s, they started to target different groups of buyers and built in different sizes, styles and in all parts of the city. This reflects the effect of the emergence of new forms of capital accumulation which led to a more diversified and segregated class structure. This diversity is of economic, social and cultural origin, which is reflected on the identity of each gated community having particular names, architectural styles, and amenities, size of the land and housing units, and advertising campaigns (Tanulku, 2013a).

Gated Communities: Environmental Degradation and Upper-Class Stigma

Gated communities in Istanbul create two main problems: the first is associated with environmental sustainability, i.e. their damaging effect on environment and natural resources such as forests and arable lands, once owned by the locals. In this respect, they also lead to the dispossession of the locals who sell their lands off to developer companies expecting high rent value. The locals either became impoverished and started working in those communities in low-skilled jobs or left their homes because of losing their lands (Tanulku, 2012a). This creates the irony that the residents in gated communities who abandoned city centres due to concerns of urban pollution, degradation and density, complain about the same problems in the once-beautiful areas now facing dramatic growth because of them. More particularly, Istanbul’s northern suburbs experience this process stronger due to the area’s relatively higher status for the residents of gated communities who altered the topography of the area, covered with native forests. Once a symbol of escape, the north of Istanbul faces tremendous change due to the construction of gated communities as well as the infamous Third Bosporus Bridge and Airport.

The second is the stigma associated with gated communities, which are regarded as upper-class sites reflecting their wish of exclusion and retreat from urban life and problems. The irony is that while people move into gated communities in order to eliminate the stigma of large cities, symbolizing mixed immigrant culture as well as environmental degradation, once by closing themselves off from the rest into “hated communities”, they take the stigma on their shoulders due to their individualised lifestyles excluding the rest of the society. They try to eliminate this stigma either by helping the local populations, found poorer, through aid campaigns and free courses given through volunteer work, and finding jobs for them (Tanulku, 2012a) and/or accusing their richer neighbours to rely on illegal sources of income and have non-friendly attitude to outsiders (Tanulku, 2012b). In addition, despite being regarded as ideal and problem free-zones, gated communities lead to disputes between residents emerging from common resource sharing, as well as visitors coming from the outside (Tanulku, 2013a). These indicate that gated communities in Istanbul can be regarded as an urban dilemma which is found to be against the ideal of an open and democratic urban space shared and accessed by all.

Author’s note

A different version of this piece was published in http://sustainablecitiescollective.com/basaktanulku/179331/rise-gated-communities-turkey-spaces-upper-class-exclusivity-escapism-and-stigma (posted on October 1 2013)

References

Bagaeen, S. (2012) “Gated Urban Life versus Kinship and Social Solidarity in the Middle East”, in Gated Communities: Social Sustainability in Contemporary and Historical Gated Developments, Bagaeen, S. and Uduku, O. (eds.), Earthscan: London.

Blakely, E. and Snyder, M. G. (1997) Fortress America, Washington DC: The Brookings Institution Press; Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Dupuis, A. and Dixon, J. (2012) “Barriers and boundaries: An Exploration of Gatedness in New Zealand”, in Gated Communities: Social Sustainability in Contemporary and Historical Gated Developments, Bagaeen, S. and Uduku, O. (eds.), Earthscan: London.

Genis, S. (2007) Producing Elite Localities: The Rise of Gated Communities in Istanbul, Urban Studies, 44 (4): 771-798.

Low, S. (2003) Behind the Gates: Life, Security and the Pursuit of Happiness in Fortress America. New York, Routledge.

Oncu, A. (1988) The Politics of the Urban Land Market in Turkey: 1950-1980, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 12 (1): 38-64.

Oncu, A. (1997) The Myth of the Ideal Home Travels Across Cultural Borders to Istanbul, in Oncu, A. and Weyland, P. (eds.) Space, Culture, Power: Struggles Over New Identities in Globalizing Cities, London: ZED.

Keyder, C. (2000) Arka Plan. In: Keyder, C. (Ed.) Istanbul Kuresel ile Yerel Arasinda. Metis, Istanbul.

Roitman, S. (2010) Gated communities: definitions, causes and consequences, Urban Design and Planning, 163 (1): 31–38.

Roitman, S. and Giglio, A. M. (2012) “Latin American Gated Communities: The Latest Symbol of Historic Social. Segregation” in Gated Communities: Social Sustainability in Contemporary and Historical Gated Developments, Bagaeen, S. and Uduku, O. (eds.), Earthscan: London.

Sassen, S. (2012) “Urban Gating: One Instance of a Larger Development”, in Gated Communities: Social Sustainability in Contemporary and Historical Gated Developments, Bagaeen, S and Uduku, O. (eds.), Earthscan: London.

Suarez Carrasquillo, C.A. (2011) Gated Communities and City Marketing: Recent Trends in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, Cities, 28 (5): 444-451.

Tanulku, B. (2012a) Gated Communities: From Self-Sufficient Towns to Active Urban Agents, Geoforum, 43 (3): 518-528.

Tanulku B. (2012b) “Moral Capitalism” and Gated Communities: An Example of Spatio-moral Fragmentation in Istanbul,http://citiesmcr.wordpress.com/2012/11/27/moral-capitalism-and-gated-communities-an-example-of-spatio-moral-fragmentation-in-istanbul/, 27 November.

Tanulku, B. (2013a) Gated Communities: Ideal Packages or Processual Spaces of Conflict? Housing Studies, 27 (3): 937-959.

Tanulku, B. (2013b) “Istanbul in Transformation”, http://www.opendemocracy.net/opensecurity/basak-tanulku/istanbul-in-transformation

Tomba, L. (2012) “Gating Urban Spaces in China: Inclusion, Exclusion and Government” in Gated Communities: Social Sustainability in Contemporary and Historical Gated Developments, Bagaeen, S. and Uduku, O. (eds.), Earthscan: London.

Webster, C., Glasze, G. and Frantz, K. (2002) The global spread of gated communities, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 29 (3): 315–321.

Wu, F. (2010) Gated and Packaged Suburbia: Packaging and Branding Chinese Suburban Residential Development, Cities, 27 (5): 385-396.

[1]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Istanbul_panorama_and_skyline.jpg, 2 July 2012, 11:13,http://www.flickr.com/photos/bmorlok/7653851478/)

[2] http://tuik.gov.tr/UstMenu.do?metod=temelist#

Author Biography

Basak Tanulku obtained PhD degree in Sociology from Lancaster University, the UK for the research “An Exploration of Two Gated Communities in Istanbul, Turkey” (2010). She works on cities, particularly socio-spatial fragmentation, gated communities and similar developments in Turkey; space and identity; urban vacant lands and buildings; urban social movements and protest camps; urban transformation and its effects on urban communities, life and heritage. She is also interested in the human-animal interaction, the protection of cultural heritage and gender issues. She also has a strong background on the socio-political context of Turkey and the Middle-East. She wrote blogs for different web sites and published articles in peer-reviews journals, such as Geoforum and Housing Studies.

Contact email: tanulkub@gmail.com