30

Alan Latham, University College London, and Peter Wood, The Open University, UK

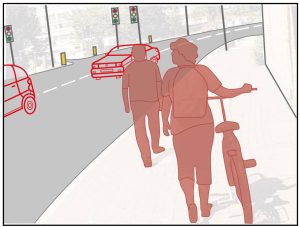

London is not always an easy place to cycle. Take the case of Elle and Tara. They are two budding commuter cyclists travelling from Earlsfield in south London towards Richmond Park. Nearing the park, their journey takes them through a grassy heath and then along a small lane of terraced houses. They start to relax. Then without warning, they find themselves having to join a busy A-road via a non-signal controlled T-junction. A thick snake of traffic – cars, vans and lorries – is crossing their path.

Reaching the mouth of the junction, Elle and Tara glide to a stop. They look left then right. Deciding against cycling through the traffic they dismount their bikes, wheeling them across the mouth of the junction and up on to the sidewalk. Standing on the kerb Elle and Tara confer, and then walk 100 metres up the street to a pedestrian crossing. Using the crossing, they finally make it across the A-road. They then remount their bikes and continue their journey.

What are we to make of Elle and Tara’s cycling? One interpretation is simply that it represents failure: of Elle and Tara as cyclists and of space for cycling in English cities. Certainly the previous vignette indicates how hard it can be to cycle competently and comfortably on roads in cities like London. But the episode can also be interpreted differently. It could be seen as a demonstration of the diverse ways that people manage to navigate the road infrastructure. It shows how people practically manage to inhabit this infrastructure, making it a part of their daily movements.

A great deal of the debate on cycling in the UK has focused on the provision and use of road infrastructure for cyclists. Campaigners have repeatedly highlighted how poor and inconsistent that provision is. Many commentators have suggested that cyclists fail to use the road infrastructure properly. Amidst all this debate it is surprising how little is known – whether by transport engineers, social scientists or cycling activists – about how cyclists ‘in the wild’ actually use roads. This is what our research set out to understand.

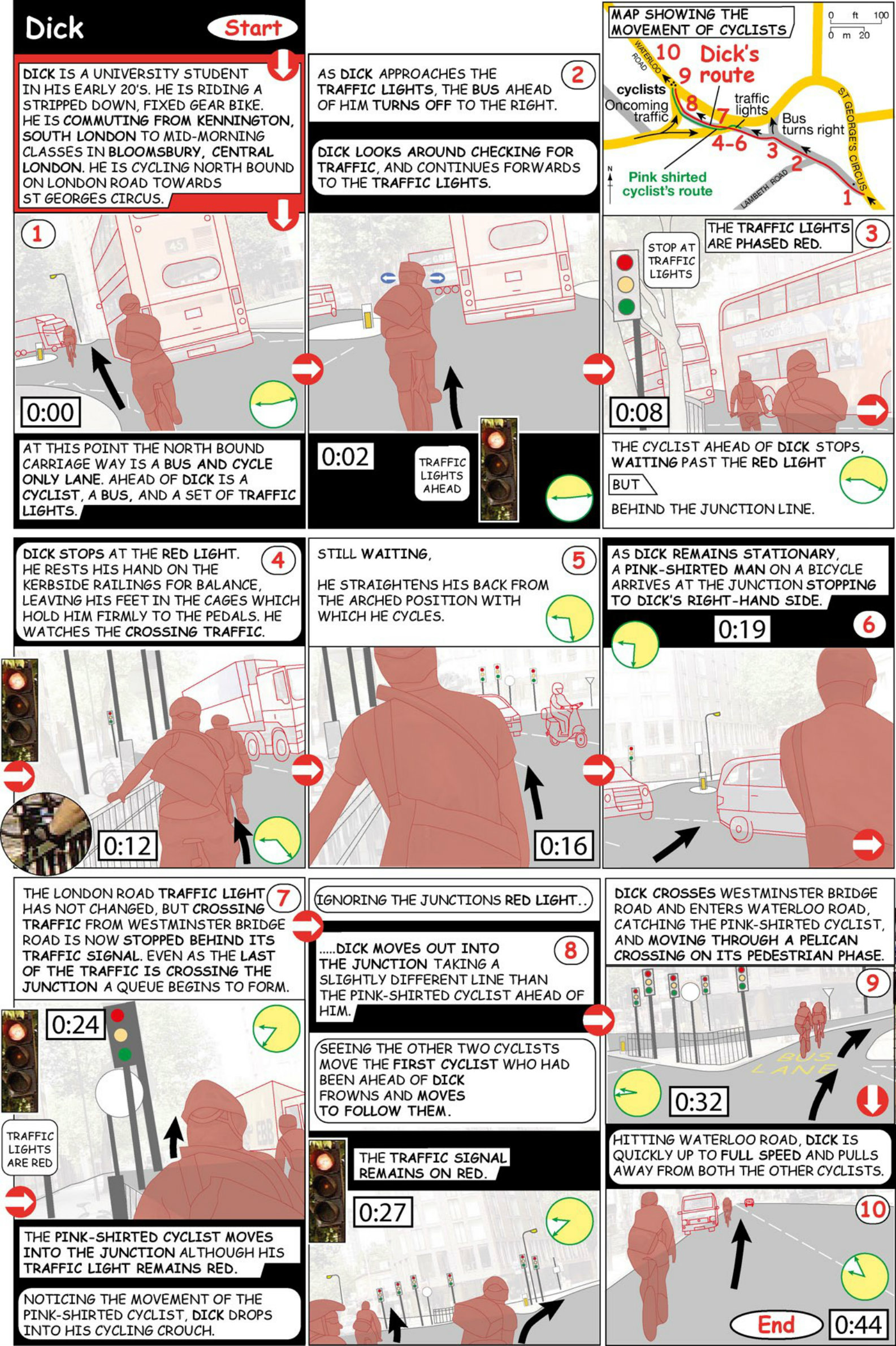

Filming a number of volunteer commuter cyclists as they travelled across the city, we studied how riders practically used the infrastructures they came across. Investigating the fine detail of everyday cycling, we discovered that people’s movements were far more variable than you might expect! Even amongst experienced cyclists, their actions were adapted to the oddities and opportunities which they encountered en route. For example, whilst Elle and Tara created a break in the traffic by walking to a pedestrian crossing, another volunteer called Dick would cross through red lights because they made a break in the traffic both across and behind him. Whilst cycling’s growth means that cyclists in inadvertent rush hour pelotons might seem to support each other, some slower riders (such as our volunteer Gail) seemed left behind and remained unprotected. Finally, the marginal infrastructural changes that allowed our volunteer Rachel to ride on the sidewalk were not particularly fast or easy to use. They got her off the road in a dangerous situation, but not much more.

As a contribution to the national cycling debate, our research seems to suggest three main findings:

Firstly, that cycling is not as simple as many people might imagine. What is possible for one rider may not be feasible, convenient or reassuring for another.

This leads to our second suggestion- that diagrams showing cyclists’ movements from an (almost) point-of-view perspective could be a valuable, under-used means of explaining this. The image accompanying this blog is taken from an extended storyboard in our journal article. As demonstrated in the paper, such methods might be used by campaigners as an intuitive but rigorous way of explaining the problems and opportunities of infrastructure. Together these findings might address recurring misunderstandings. That could include cases of well-intentioned designers and experienced cyclists failing to understand why differently skilled users might find spaces difficult to use. It could also create new methods for explaining to mystified road users why cyclists take the routes they do, such as avoiding the cycle path or riding in the centre of the lane.

Finally, by developing new ways to describe how cyclists use the street, we might start to imagine and argue for new types of space for cycling. By looking at how so much existing infrastructure treats the cyclist as either an odd car or an odd pedestrian, we might start to design spaces for cycling that are more focused on the bike’s own strengths and weaknesses.

With the new requirement to create a Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy in the next parliament, we hope that our research will support the academic study and public campaigning that suggests how future investment could best be spent.

Origins of the blog and further reading

This blog post was originally written for the CTC, the United Kingdom’s national cycling charity. It aimed to explain the immediate implications of recent peer-reviewed research to an audience of industry professionals, campaigners and the general public. The post can be found at – www.ctc.org.uk/blog/samjones/inhabiting-infrastructure-explaining-cyclings-complexity

The journal paper referred to in this post is open access thanks to The Open University’s Research Councils UK funding: Latham, A., & Wood, P.R.H. (2015). Inhabiting infrastructure: Exploring the interactional spaces of urban cycling. Environment and Planning A, 47(2): pp. 300-319

Author Biographies

They are researchers from the Departments of Geography at University College London and The Open University.

Dr Alan Latham  is an urban geographer whose research focuses on three key areas: Sociality and urban life; Globalization and the cultural economy of cities; Corporeal mobility.

is an urban geographer whose research focuses on three key areas: Sociality and urban life; Globalization and the cultural economy of cities; Corporeal mobility.

Contact email: alan.latham@ucl.ac.uk.

Dr Peter Wood is a social geographer studying Sustainability policy, Changing urban lives, and Mobile embodied experience. His work on the project was funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council grant ES/I019790/1.

Contact Details:

Email: peter.wood@open.ac.uk

Twitter @canihazresearch