17

Jonas Bylund, JPI Urban Europe

Well, how do we go about setting up an ambitious programme with thematical priorities in the field of urban development? It could be a mess. It could be superficial and just full of buzzwords. It could also be fabulously collaborative adventure! The latter, we hope. This piece is focused on why and how JPI Urban Europe composes its Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda (SRIA): Transition towards sustainable and liveable urban futures. The SRIA is to present a plan for the next five years (until 2020) on what and how we will orient the JPI Urban Europe calls for research and innovation as well as related activities that we do concerning urban development in Europe. Although this chapter is nicely located in the section on engaging citizens, these are but one group we actually needed to engage among many other kinds of publics or actors (Marres 2010). However, the SRIA is also set to engage more and varied forms of publics into urban transition over the coming years!

Why do we need a SRIA?

Why do we need an agenda? Couldn’t we just keep in doing it call by call? Simply because we need a reference, a plan. Of course. No project can work without one. But we also need to allow other actors in policy and research and innovation to know what we plan to do, so to align our activities. This is important since it concerns the many ‘wicked issues’ in the current landscape of urban sustainable development activities, where creative work is required to balance holism with silos, to find ‘bite-size chunks’.

The working title of the SRIA is ‘Transition towards sustainable and liveable urban futures’. An agenda in this field has one main predicament. The ‘urban’ is more than one, but less than many (Mol 2002). Or with another metaphor: from a research and innovation point of view, it is an archipelago of discplinary islands and clusters of epistemic communities.

Urban research, urban studies, or urbanism – however we may call the field of inquiries concerned with urban phenomena – can be seen as an archipelago. The analogy is borrowed from Michel Serres (1980), who used it to think of science as a whole: there are islands of order or systematized knowledges which differ in terms of topics, issues, and method; and much water in between, which stands for the unordered and unknown.

JPI Urban Europe is not concerned with discrete topics such as Alzheimer’s disease or climate change, however terribly complex and costly they are to address in their own right. Hence, we can rarely talk of a state of the art or the research frontier. This is not always clear to people outside the field, including academics (perhaps it is not always clear for academics within the field either). Time and again the urge seems to irrupt to single out one island and have it define the whole field to clear out the mess. Of course, this is also why the ranking of specific topics are frustratingly difficult and controversial within the field, and also why holism is so much easier said than done. Because we seem to have a hard time understanding differences in dialect over the archipelago, there is simply no one shared language. So, the field will remain rather messy as long as we call it ‘urban’.

Nowadays the call for more substantial interdisciplinary efforts to bridge the waters is ubiquitous. To connect two or more islands not yet connected is an urgent matter, as is knowledge transfer between them and beyond to policy, planning, politics, and society at large. However, and perhaps because of the varying success and failures of these endeavours, the archipelagic landscape remains unevenly infrastructured. Hence, the field of urban research in itself raises similar problems to those concerning interdisciplinarity in environmentalism and the sciences in general. This is many ways reflected in the policy and decision-making setting: this arena could be seen as an archipelago as well. So, bottom line, the field of urban development – particularly sustainable urban development – is strongly characterized by what is now commonly called silos or silo practices.

However, and here is the gist of why the SRIA is pertinent: it is obviously no use to merely lump all knowledge together into one holistic urban porridge. I fear assemblage thinking may sometimes end up here – similar to a simple call for holism in general. This is of course why integrated is a better notion, if not optimal – an ‘integrated urban development’? Law, in his reflection on how to deal with ‘wicked issues’ in connection with the Anthropocene, proposed that we should try to find the ‘bite-size chunks’. That is, not to break down silos completely, but not to acknoweldge them fully either (Law 2014).

How does it work in practice?

Given the ‘participatory turn’ and the ‘new engagement agenda’ across policy discourses and research bodies such as Future Earth, there are ample times when issues and points warrant co-creation but also sincere reflexive work as part of this (cf. e.g. Beck 2012; Bijker 2010; Gibbons 1999; Jasanoff 2007). Granted, this notion requires a more substantial reflexivity in responsible research and innovation (RRI) so that it does not ‘sink in the hype’ and become a ‘magic buzzword’ (cf. Swart et al. 2014). Although this is not a substantial discussion on variants and models of co-creation, it at least signals an element of reflexivity is due when we throw around this notion.

The SRIA co-creation was not modeled after a systematic ‘scientific’ method, but rather from a general principle to allow and enable as many kinds of groups and communities (actors) to have a say on urban developments.

The main warrant, in our case, was simply that it would not be right to have only one kind of stakeholder, one kind of actor to draw up the document. Because of what the agenda sets out to achieve, a substantial support to urban sustainable transition, mainly in Europe but not exclusively, it was important to keep in mind that there are no single and omniscient sources to inform the content – to achieve a true break away from the technocratic rationalism that still lingers in the field.

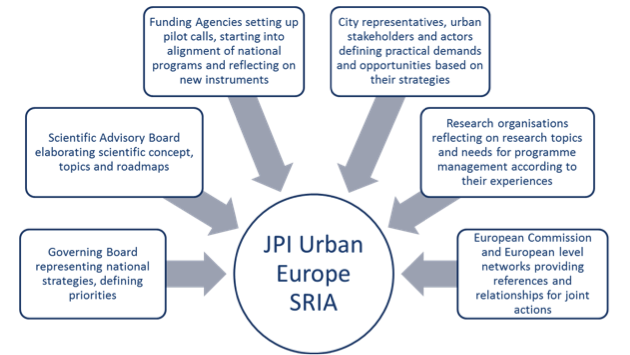

The agenda is intended to be multi-level in its nature: individual research adn innovation groups, civil servants in urban management, civil society organisations, national policy makers, and European policy and urban development actions as well as ‘international’ or global organisations shuld be find it perusable. So, this is also important when considered from both ethical and design point of views, since the SRIA had to align a plethora of city strategies, as well as national, European, and global policy priorities and research programmes (see Figure 1). The SRIA had to consider the needs of urban civil society and those actors who work with urban issues on a daily basis. At the same time, it had to comprise a visionary programme of research and innovation to enable urban sustainable development.

Designing the SRIA was set out as an iterative approach, which starts with the academic scientists – in the form of our Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) – to build a skeleton of the latest scientific findings. Of course, there were early starts or, to compare with what many writers do as a rule, ‘false-starts’ to get the process going. For each time we realised the SRIA wouldn’t hold after dialogues with stakeholders, it was back to the drawing table to redesign the outline. These regular reflections and discussions on ideas, topics, and implementation measures have been the main feature of the co-creative approach.

Not all actors are comfortable in a workshop environment or participatory approach. To engage ‘hard to reach’ actors in the crafting of the SRIA, alternative interfaces were required. We took advantage of a high profile event. At the event, European Union representatives and urban policy makers’ discussions provided input for the SRIA. Another interface was to set up national consultations by the JPI Urban Europe member states: the national contact points were asked to deliberate the SAB Megatrends paper with national stakeholders. At this point, the urban social innovation project SEiSMiC (http://www.seismicproject.eu/) and the Urban Europe Research Alliance (UERA; http://jpi-urbaneurope.eu/activities/uera/) also provided very helpful input.

The SAB drafted a note, an outline, to serve as the next skeleton in the following iteration. This phase, cities’ representatives and projects already funded within JPI Urban Europe were invited to dicsuss and state priorities. The note was subsequently molded into a more policy-oriented text. Representatives from the Governing Board, European Commission, and scientific expertise engaged in a transdiscipinary workshop. As well as an open survey format online to invite as broad participation as possible.

Polyrhythmic patterns and multi-modality

Time. It takes time because different kinds of actors work with different rhythms. Time differs nationally in terms of ‘policy cycles’, and also between academia and policy, and amongst urban practitioners. SRIAs are ruled by the ‘polyrhythmic’ setting and deadlines can be quite plastic (no news there, really). Additionally, some actors are quite unused to this level of input in urban agendas. Finally, there is also the challenge of composing and articulating the SRIA in at least two kinds of registers at once: frontstage (policy oriented) and backstage (technical issues) (Bijker 2010; cf. Boltanski & Thévenot 1999). And still to do this without the sense of a sharp contrast between the modes, so as enable movement between the them. Now, with all this in place, let’s get on the task of co-creating what the SRIA tells us to do!

References

Beck, S. (2012) ‘The challenges of building cosmopolitan climate expertise: the case of Germany’, in WIREs Climate Change, 3, 1–17.

Bijker, W. E. (2010), ‘Different forms of expertise in democratising technological cultures: Experiences from the current Societal Dialogue on Nanotechnologies in the Netherlands’, in Tecnoscienza, 1(2), 121–140.

Boltanski, L. & Thévenot, L. (1999) ‘The sociology of critical capacity’, in European Journal of Social Theory, 2(3), 359–377.

Coutard, O., Finnveden, G., Kabisch, S., Kitchin, R., Matos, R., Nijkamp, P., Pronello, C., & Robinson, D. (2014) Urban Megatrends: Towards a European Research Agenda, A report by the Scientific Advisory Board of JPI Urban Europe, March 2014.

Gibbons, M. (1999) ‘Science’s new social contract with society’, in Nature 402, C81–C84.

Jasanoff, S. (2007), ‘Technologies of humility’, Nature, 450 (1), 33.

Law, J. (2014) ‘Working well with wickedness’, in Klingan, K., Sepahvand, A., Rosol, C. & Scherer, B. M.(eds.), Textures of the Anthropocene: Grain vapor ray (pp. 157–176) Berlin: Revolver Publishing.

Marres, N. (2010). ‘Front-staging Nonhumans: Publicity as a Constraint on the Political Activity of Things’. In B. Braun & S. J. Whatmore (Eds.), Political Matter: Technoscience, Democracy, and Public Life (pp. 177-210). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Mol, A. (2002), The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice, Durham: Duke University Press.

Serres, M. (1980), Le passage du Nord-Ouest, Hermes V, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.

Swart, R., Biesbroek, R., & Capela Lourenço, T. (2014), ‘Science of adaptation to climate change and science for adaptation’, in Frontiers in Environmental Science, 2, 1–8.

Author Biography

Jonas Bylund is part of the JPI Urban Europe Management Board since 2013. His main responsibility in 2014 is science-policy communication and to develop urban research and innovation funding calls with affiliated funding agencies as well as other initiatives. Since 2013 he is also employed at IQS, the Swedish Centre for Innovation and Quality in the Built Environment. He is trained in human geography and social anthropology. He is affiliated to the Department of Human Geography, Stockholm University, with a research focus on the knowledge practices in planning and environmental sciences. His PhD thesis Planning, Projects, Practice (2006) investigated a local investment programme concerning new environmental technologies in Stockholm urban development and was an attempt to translate actor-network theory into planning studies. He is an experienced lecturer in urban and regional planning, with a particular focus on epistemology and ontology in the social sciences. He is also a consultant with Urbanalys.

Contact email: jonas.bylund@jpi-urbaneurope.eu