63

Leslie Mabon, Robert Gordon University, UK

Iwaki is a city of 300,000 people. Two hours by high-speed train from Tokyo, it has a strong industrial heritage based around coal, car manufacture and chemicals production. It also has a reputation for quality marine and agricultural produce, and a tourist sector emerging to offset the decline of mining. This would make an interesting sustainable urbanisation study in its own right, but Iwaki’s urban core also happens to be less than 50 kilometres south of the Fukushima Dai’ichi nuclear power plant.

‘You may think the experience in Fukushima is unusual. Yes, the accident itself was unusual, but the consequent social issues that torment the people in Fukushima are something common to the people suffering from disasters, wars, incidents and disputes’

So reads the header on a poster in the Fukushima Future Center for Regional Revitalization, a concrete-and-linoleum building standing atop a hill overlooking Fukushima University. Indeed, post-disaster life in Iwaki – the largest city in Fukushima Prefecture – indicates how a large-scale, rapid and potentially irreversible environmental change can affect urban spaces.

First, though, a reminder of what happened four years ago. A magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck off the coast of north-east Japan on 11 March 2011, triggering a tsunami reaching up to forty metres in height and stretching up to ten kilometres inland. More than 15,000 people were killed and over 2,000 remain missing. Iwaki suffered notable damage from the earthquake and tsunami, particularly in coastal areas, with the immediate loss of 293 lives. The earthquake and tsunami also took out the cooling systems for the Fukushima Dai’ichi nuclear power plant, which triggered hydrogen explosions and large releases of radioactive material over land and sea that led to the evacuation of around 120,000 people from their homes in Fukushima Prefecture.

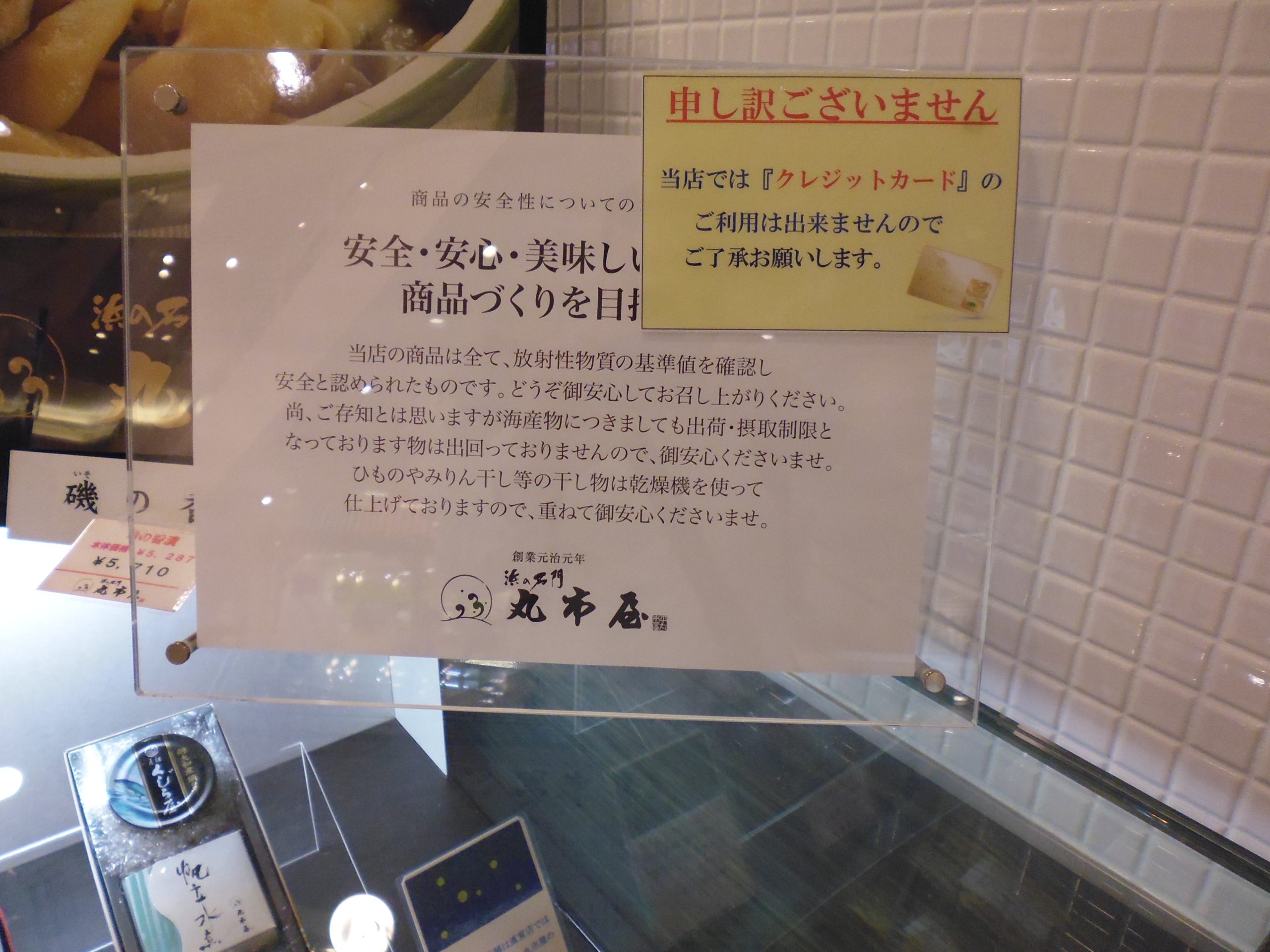

Although no compulsory evacuation orders were issued in Iwaki and decontamination has proceeded alongside post-tsunami and earthquake reconstruction, effects of the nuclear disaster continue to permeate everyday life. ‘Normal plus alpha’ is how someone explained daily living in the urban parts of Fukushima to me, which seems very apt. For ‘normal life’ in Iwaki is punctuated with reminders of the small but nonetheless present quantities of radioactive matter that remain scattered over the built environment. Digital meters at roadsides and in public spaces display current atmospheric counts. Newspapers and TV bulletins report daily radiation levels. Some supermarkets and eateries provide signs assuring customers that produce has been screened, others display boards demonstrating radiation monitoring processes, and others plant QR codes on produce to direct consumers to more detailed screening information.

Radioactivity levels within Iwaki are comparatively low, but it is also true that it is hard to measure an individual’s precise level of exposure to radiation. Interviewed civil servants and academics acknowledged the limitations of monitoring efforts. For instance, fixed point monitoring posts do not take into account the exposure a human may receive as they move around the environment, and decontamination conducted in towns and cities does not so thoroughly extend to the forested and mountainous areas that urban dwellers may visit for recreation. Daily life in Fukushima – even in spaces like urban Iwaki – continues against a backdrop of uncertainty and indeterminacy (Morris-Suzuki (2014) discusses this in depth). Global climatic change or pollution from emerging industries may likewise lead to conditions of uncertain environmental effects within urban spaces. In this regard, the situation in Iwaki – whilst clearly extreme in origins and nature – may give insight into challenges for ‘sustainable urban life’ in a context of environmental risk and uncertainty. Do we need to pay attention to factors in the environment that previously went unmarked? What to monitor, and how to monitor it? How to acknowledge – and live with – environmental uncertainty?

There are also wider socio-cultural dimensions to large-scale, sudden and long-term environmental change. Iwaki was not evacuated after the nuclear accident, but towns and villages to the north were. Many remain unable to return home due to high contamination levels, a situation likely to continue into the future. As one of the nearest adjoining settlements, Iwaki took a large proportion of evacuated people and prefabricated temporary housing sprang up around the city’s urban fringes to provide accommodation. Add to this an influx of workers employed in the cleanup efforts at the plant and its environs, and the result is a population increase of 20,000 in Iwaki post-disaster. Such demographic change affects social dynamics. In late 2014, Reuters ran a piece on perceived tensions between pre-disaster residents and resettled citizens over perceived differences in compensation payments (Saito & Slodkowski, 2014).

The disaster has also touched a key source of pride for Iwaki – fisheries (Mabon & Kawabe, in press). Concerns over contamination mean coastal fishing in Iwaki is currently limited to a ‘trial’ basis, with produce released for sale if radioactivity monitoring and screening is satisfactory. Aside from economic impacts, members of Iwaki’s fishing communities spoke of a desire to get back out fishing, and lamented the reduction in opportunities for interaction with each other and with the community that fishing affords. As environmental change and energy crises take hold, it may well be that urban spaces have to accommodate displaced people, or that previously meaningful practices are no longer viable. The current situation in Iwaki may thus give an indication of the changes that urban spaces face as they come under social and environmental pressure.

It is important not to downplay or ‘normalise’ the Fukushima Dai’ichi nuclear disaster, and to remember that the heterogeneity of levels of contamination – and thus experiences of post-accident life – vary greatly. This makes drawing generalisations difficult. Yet at the same time, it may also be true that living with uncertainty, demographic change and effects on the practices that matter to us is something that will affect urban spaces as the global climate changes and energy consumption patterns shift. Looking to the governance of urban spaces like Iwaki now may help to be better prepared for the wider issues for sustainable urban life that lie ahead.

The research on which the observations in this blog post are based was funded through a Japan Foundation Fellowship (Short-Term).

References

Mabon, L. and M. Kawabe. In Press. Fisheries in Iwaki after the Fukushima Dai’ichi nuclear accident: lessons for coastal management under conditions of high uncertainty? Coastal Management.

Morris-Suzuki, T. 2014. Touching the Grass: Science, Uncertainty and Everyday Life from Chernobyl to Fukushima. Science, Technology and Society 19 (3): 331-362.

Saito, M., and A. Slodkowski. 2014. Fukushima fallout: resentment grows in nearby Japanese city. Reuters Online. 31 August 2014. http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/08/31/uk-japan-nuclear-resentment-idUSKBN0GV0XN2014083

Author Biography

Leslie Mabon is a Lecturer in Sociology at Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen, Scotland, United Kingdom. His research focuses on less ethically clear-cut aspects of energy and environmental governance, with a particular interest in the social dimensions of risk and uncertainty in marine and coastal environments. The material on which this post is based is part of a larger project Leslie is currently involved in on fisheries and marine radioactivity in Japan after the Fukushima disaster, and he is also currently continuing research in his native north-east Scotland on the future of the North Sea in response to energy and climate change challenges. Leslie holds a PhD in Geography.

Contact details:

Blog: energyvalues.wordpress.com

Twitter: @ljmabon