33

Anna Mary Cooper and Alex Clarke-Cornwell, University of Salford, UK

The link between the built environment and the impact on people’s health is well known, and the interest in this area is continuing to grow at pace (Jackson, Dannenberg, & Frumkin, 2013). In developed countries, we are seeing illness and disease related to lifestyle risk factors becoming the biggest risk to mortality and hospital admissions. Lopez (2012), in the book ‘The Built Environment and Public Health’ writes:

“The built environment provides the framework for how daily lives are conducted, influences health across life spans, and represents important pathways through which individuals come into contact with many health risks” (p. 4)

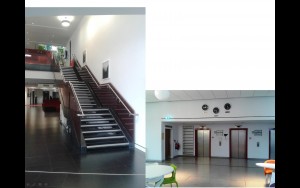

To start with we want to give you an example from the University of Salford (UK) of how buildings can impact our movement. For many, the workplace has a large impact on our physical activity and sedentary behaviour, through both building design and workplace culture (Finch, Wilson, & Dugdill, 2012). The images below show examples of two buildings on the University of Salford campus. The first is a new building (2011) where the stairs are clearly visible as you enter through the main doors, and the lift (elevator) is at the back of the building (by the red carpet). The second is an older building (1966) – our building – where the lifts are visible and the stairs are through the small door on the left hand side; the stairs are not in view of those travelling around the building.

Through these two images, you can see how design can impact our public health in terms of activity. In the first one, would you (if you didn’t need to) go looking for the lift? Then in the second one, would you know where to find the stairs, or would you use the lifts as they dominate the eye line?

Stair location is one example of something that influences our decisions to be active or sedentary in our everyday lives. There are an increasing number of examples of how places are trying to encourage people to change their behaviour and choose the stairs rather than the lift, including: the #pianostairs that became a functioning keyboard when walked on; displaying calories used per step; and motivational messages to keep you climbing.

What other ways can a building’s design and setting influence us to be more active at work?

With the development of technology, activity levels at work have declined over the last century; the introduction of desk dependent computer based jobs has seen an increase in the number of sedentary occupations. Over recent years leisure-time activity has remained relatively stable, whilst workplace activity has decreased, which in turn has led to an increase in time spent in sedentary behaviours (Bassett, Pucher, Buehler, Thompson, & Crouter, 2008). For those who are economically active, sedentary behaviour at work may represent the majority of their sedentary time; therefore, the workplace is an ideal setting to influence active behaviour and replace part of our sedentary time with light physical activity.

Sedentary behaviour is known to be independently associated with a number of health-related outcomes (e.g. cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, type 2 diabetes, some cancers and premature mortality) (Dalkilinc, 2015; Wilmot et al., 2012). Musculoskeletal disease and mental ill-health are responsible for the majority of work-related ill-health and days absent from work in the UK (Health and Safety Executive, 2012); however, physical activity is known to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression (Landers & Arent, 2012), and the use of sit-stand desks has been found to relieve some musculoskeletal complaints (Husemann, Von Mach, Borsotto, Zepf, & Scharnbacher, 2009). Sedentary behaviour is associated with reduced productivity at work through presenteeism (Brown, Ryde, Gilson, Burton, & Brown, 2013); therefore, it is conceivable that increasing activity in the workplace has the potential to increase productivity and decrease absenteeism.

The workplace environment and built environment should ideally enhance both health and productivity (Sallis & Owen, 1999). New buildings can be designed to encourage movement through: location, which impacts on transportation options; structural design, to include activity friendly features; and services, such as gym facilities and bicycle storage. The built environment in which we work should ideally support healthy, rather than unhealthy behaviours; for many though, buildings in urban spaces are in established locations and can have limited natural design features. Changes to building design are dependent on available resources – but, we can make small modifications to our office settings and our individual behaviours, which can consequently increase physical activity and productivity in the workplace (Active Design Guidelines, 2010):

- alternating between sitting and standing – sit-stand desks can create a significant increase in energy expenditure and can be easy to introduce into office buildings (Levine & Miller, 2007)

- encouraging more workplace intercommunication; for example, walking to speak to co-workers rather than sending emails or having more welcoming spaces for people to meet

- having standing meetings or walk and talk meetings (Merchant, 2013) – with buildings designed to help facilitate this (e.g. The RBS building in Scotland with internal courtyards and walkways)

- supplying painting/artwork/motivational quotes in stairwells and walking routes to make them more appealing to users and reduce the use of lifts (which also impacts upon carbon footprints)

- displaying prompts to use the stairs – informational (i.e. calorie expenditure, health benefits) and motivational signage (for example StepJockey)

- providing centralised areas that encourage people to get up from their desk and engage in brief bouts of walking.

- locating facilities (such as bathrooms, lunch areas, mail room), a walking distance from offices to promote walking and also considering the design of these to ensure they are welcoming and used

- and using computer applications to encourage short breaks from sitting every hour (Beddhu, Wei, Marcus, Chonchol, & Greene, 2015)

We want to leave you with a question – What more can those who work in areas relating to sustainable urbanisation and public health do to encourage people to sit less and move more whilst at work in urban places?

Finally, we want to acknowledge the late Professor Lindsey Dugdill and the influence of her work and interests in shaping the idea for this blog.

References

Bassett, D. R., Pucher, J., Buehler, R., Thompson, D. L., & Crouter, S. E. (2008). Walking, cycling, and obesity rates in Europe, North America, and Australia. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 5(6), 795–814.

Beddhu, S., Wei, G., Marcus, R. L., Chonchol, M., & Greene, T. (2015). Light-Intensity Physical Activities and Mortality in the United States General Population and CKD Subpopulation. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 10(7), 1145–53. doi:10.2215/CJN.08410814

Brown, H. E., Ryde, G. C., Gilson, N. D., Burton, N. W., & Brown, W. J. (2013). Objectively measured sedentary behavior and physical activity in office employees: relationships with presenteeism. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 55(8), 945–53. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e31829178bf

Dalkilinc, M. (2015). Why sitting is bad for you. TEDEducation. YouTube. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/wUEl8KrMz14

Department of Design and Construction, Deparment of Health and Mental Hygiene, Department of Transportation, & Department of City Planning. (2010). Active Design Guidelines: Promoting Physical Activity and Health in Design. New York.

Finch, E., Wilson, P., & Dugdill, L. (2012). Stimulating Physically Active Behavior Through Good Building Design. In S. Mallory-Hill, W. F. E. Preiser, & C. G. Watson (Eds.), Enhancing Building Performance (1st ed., pp. 203–212). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Health and Safety Executive. (2012). Health and Safety Executive Annual Statistics Report for Great Britain.

Husemann, B., Von Mach, C. Y., Borsotto, D., Zepf, K. I., & Scharnbacher, J. (2009). Comparisons of musculoskeletal complaints and data entry between a sitting and a sit-stand workstation paradigm. Human Factors, 51(3), 310–20.

Jackson, R. J., Dannenberg, A. L., & Frumkin, H. (2013). Health and the built environment: 10 years after. American Journal of Public Health, 103(9), 1542–4. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301482

Landers, D. M., & Arent, S. M. (2012). Physical Activity and Mental Health. In G. Tenenbaum & R. C. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of Sport Psychology (3rd ed., pp. 467–491). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Levine, J. A., & Miller, J. M. (2007). The energy expenditure of using a “walk-and-work” desk for office workers with obesity. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(9), 558–561. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.032755

Lopez, R. (2012). The Built Environment and Public Health. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass.

Merchant, N. (2013). Got a meeting? Take a walk. TEDTalks. YouTube. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/iE9HMudybyc

Sallis, J. F., & Owen, N. (1999). Physical Activity and Behavioral Medicine. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Wilmot, E. G., Edwardson, C. L., Achana, F. A., Davies, M. J., Gorely, T., Gray, L. J., … Biddle, S. J. H. (2012). Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia, 55(11), 2895–2905.

Author Biographies

Dr. Anna Cooper is a Lecturer in Public Health at the University of Salford, with a background in Psychology and working therapeutically with children. The ongoing goal of her teaching and research is focused around global public health, accelerometers, childhood, behaviour change, transport, interventions and oral health. Anna also has research interests around the use of mHealth/applications within interventions, evaluating interventions, and the design of apps to collect children’s research data. Anna is also involved in research around cardiovascular health checks in North West England. Anna’s PhD evaluated a school based oral health programme with primary school children.

Dr. Anna Cooper is a Lecturer in Public Health at the University of Salford, with a background in Psychology and working therapeutically with children. The ongoing goal of her teaching and research is focused around global public health, accelerometers, childhood, behaviour change, transport, interventions and oral health. Anna also has research interests around the use of mHealth/applications within interventions, evaluating interventions, and the design of apps to collect children’s research data. Anna is also involved in research around cardiovascular health checks in North West England. Anna’s PhD evaluated a school based oral health programme with primary school children.

Contact Details:

Email: a.m.cooper@salford.ac.uk

Twitter: @amc_83

Alex Clarke-Cornwell is a final year PhD student and researcher at the University of Salford. She has a BSc in Mathematics and an MSc in Statistics. Alex has been involved in a range of research projects that have used her experience of epidemiology and statistics. These include for example, studies relating to the burden of musculoskeletal disease in the UK, coding in general practice research databases, and evaluations of uptake of cardiovascular health checks in North West England. More specifically, her PhD focuses on the associations between sedentary behaviour and health-related outcomes in the workplace.

Alex Clarke-Cornwell is a final year PhD student and researcher at the University of Salford. She has a BSc in Mathematics and an MSc in Statistics. Alex has been involved in a range of research projects that have used her experience of epidemiology and statistics. These include for example, studies relating to the burden of musculoskeletal disease in the UK, coding in general practice research databases, and evaluations of uptake of cardiovascular health checks in North West England. More specifically, her PhD focuses on the associations between sedentary behaviour and health-related outcomes in the workplace.

Contact Details:

Email: a.m.clarke-cornwell@salford.ac.uk

Twitter: @barmyalex