Introduction

After a needs analysis is conducted, the next step in the conduct a task analysis. Task analysis for instructional design is a process of analyzing and articulating the kind of learning students are expected to know how to perform. Following the determination that an instructional need exists (needs assessment), task analysis is used to analyze that need for the purpose of developing the instruction. In this process, task analysis and instructional analysis can be designed at the same time and stage (Seels and Glasgow, 1998). Task analysis is the main part of designing courses and projects in education, industry, government, and business. There are multiple approaches for conducting a task analysis. Brown and Green (2006) list the following as popular methods:

- Jonassen, Hannum and Tessmer’s Approach (1989)

- Morrison, Ross and Kemp’s Three Technique (2004)

- Dick, Carey, and Carey Instructional Analysis (2001)

- Smith and Ragan’s Analysis of the Learning Task (2005)

This chapter will detail the Smith and Ragan’s Analysis of the Learning Task method (2005).

Smith and Ragan’s Analysis of the Learning Task

Instead of using the term task analysis, Smith and Ragan chose to characterize their method as analysis of the learning task. They describe the key difference as “transforming goal statements into a form that can be used to to guide subsequent design” (Smith and Ragan, p. 76). The influence of Robert Gagne and Charles Reigeluth in their emphasis of a conditions based instructional design model is illustrated in this analysis. Brown and Green (2006) describe that the information-processing analysis in Smith and Ragan’s approach as the key step in the process.

An overview of Smith and Ragan’s Analysis of the Learning Task (2005):

- Write a Learning Goal

- Determine the types of learning of the goal

- Conduct an information-processing analysis of that goal

- Conduct a prerequisite analysis and determine the type of learning of the prerequisites

- Write learning objectives for the learning goal and each of the prerequisites

Learning Goal

The Learning goal describes the knowledge the learner is expected to obtain as a result of instruction (Mager, 1962). Normally, they start from very broad statements such as “learners will be able to fix a broken computer.” This phase starts to narrow the scope of the learning goal and focus on how to provide instruction. Remember, these are not objectives. Objectives will be covered specifically at the end of the process. Constructing the learning goal does not need to be complex, however it needs to be focused.

Keep in mind learning goals may already predetermined depending on your setting. K-12 education may have learning goals set on the local or state level. Trade or vocational areas, industry training boards or employers’ associations set learning goals that need to be followed for qualifications to be accredited. Even in higher education, an instructor may ‘inherit’ a course where the goals are already set, either by a previous instructor or by the academic department. These situations require flexibility with the analysis.

Examples

- When provided a malfunctioning computer, the learner will be able to diagnosis the malfunction and conduct a repair.

- When given pertinent information about student loan reform, the learner will be able to write a position letter to their United State Congress representatives.

- When provided movie information, the learner will be able to classify the movie into a specific genre.

Types of Learning

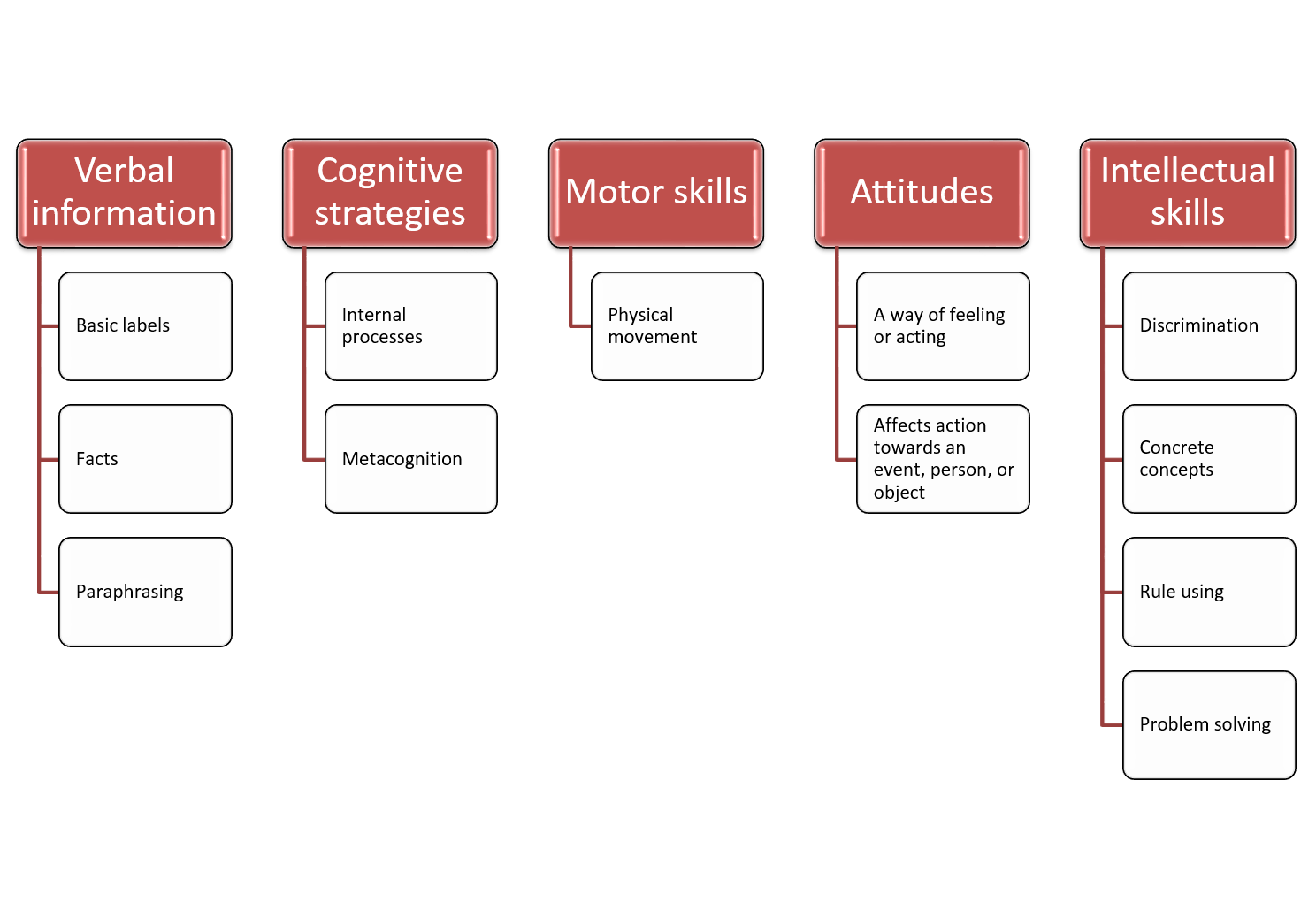

Robert Gagné posited that not all learning is equal and each distinct learning domain should be presented and assessed differently. Therefore, as an instructional designer, one of the first tasks is to determine which learning domain applies to the content. The theoretical basis behind the Conditions of Learning is that learning outcomes can be broken down into five different domains: verbal information, cognitive strategies, motor skills, attitudes, and intellectual skills (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Gagné’s Domains of Learning

Verbal information includes basic labels and facts (e.g. names of people, places, objects, or events) as well as bodies of knowledge (e.g. paraphrasing of ideas or rules and regulations). Cognitive strategies are internal processes where the learner can control his/her own way of thinking such as creating mental models or self-evaluating study skills. Motor skills require bodily movement such as throwing a ball, tying a shoelace, or using a saw. Attitude is a state that affects a learner’s action towards an event, person, or object. For example, appreciating a selection of music or writing a letter to the editor. Intellectual skills have their own hierarchical structure within the Gagné taxonomy and are broken down into discrimination, concrete concepts, rule using, and problem solving. Discrimination is when the learner can identify differences between inputs or members of a particular class and respond appropriately to each. For example, distinguishing when to use a Phillips-head or a flat-head screwdriver. Concrete concepts are the opposite of discrimination because they entail responding the same way to all members of a class or events. An example would be classifying music as pop, country, or classical. Rule using is applying a rule to a given situation or condition. A learner will need to relate two or more simpler concepts, as a rule states the relationship among concepts. In many cases, it is helpful to think of these as “if-then” statements. For example, “if the tire is flat, then I either need to put air in the tire or change the flat tire.” Finally, problem solving is combining lower-level rules and applying them to previously unencountered situations. This could include generating new rules through trial and error until a problem is solved.

Gagné’s Impact on Instructional Design

The impact Robert Gagné had on the field of instructional design cannot be understated. For example, from his initial work we can trace the evolution of the domains of learning from the Conditions of Learning through other theories such as Merrill’s Component Display Theory (1994), to Smith and Ragan’s Instructional Design Theory (1992), to van Merrienboer’s complex cognitive skills in the 4C/ID model of instructional design (1997). For the first time, those designing instruction had a process to follow, a blueprint. And almost 60 years later, Gagné’s work still serves as the basic framework all instructional designers who use systematic processes follow.

Information Processing Analysis

Once a learning goal is established and a learning domain selected, the next step is conduct the information processing analysis. Smith and Ragan (2005) describe this process as discovering the mental and physical tasks to complete the learning goal. This process is iterative; meaning that it can be done multiple times and with different information. If new tasks or questions are discovered, include it in the next analysis for further refinement.

Smith and Ragan (2005) state ten steps to complete an information-processing analysis:

- Read and gather as much information as possible about the task and content

- Convert goal into representative ‘test” question

- Give problem to several individuals who understand the task and observe

- Ask individuals questions about completing the task

- If more than one individual used, identify commons steps

- Identify shortest, least complex path to achieve task

- Identify factors that can lead to more complex path

- Select the circumstances and path that best match your goal

- List steps and decision points for your goal

- Confirm results with other experts (p. 84-85)

Example

The process listed above applies to all information processing analysis. There are specific methods to employ depending on the learning domain of your goal.

Prerequisite Analysis

Learning prerequisite analysis includes applying rules, concepts, solving problems and intellectual skills as prerequisite skills that facilitate learning of a higher skill. The analysis is often used for traditional instruction to describe learning levels before beginning a lesson and to define what must be taught, and the sequence in which to teach it. Each task has sub tasks in this process in order to reach the objectives in both simple and complex tasks.

Let’s use a previous learning goal from above: When provided movie information, the learner will be able to classify the movie into a specific genre. An information process analysis example of an action movie showed that the learner had to decide three major criteria: pacing stunt, and plot information. So a leaner must know specifics in order to make an informed judgement. This can be done in either a bulleted list with sub bullets or a graphics (similar to information processing analysis). The example listed below uses bullets for the first two steps

The first step in the in information analysis example: Recall characteristics of an action movie

The prerequisite analysis would be:

- Know what a characteristic in cinema terms

- Know what action is considered in cinema terms

- Know what a movie is considered in cinema terms

The next step was determining if the movie was fast-paced

The prerequisite analysis would be:

- Know pacing structure of a movie

- Know pacing synonyms

- Know what a plot is

- Define elements of a plot

- Know what a slow pace structure looks like

Once the prerequisite analysis is complete, the knowledge required are turned into enabling objectives. This type of objective sets additional knowledge or skills that are required into order to reach the terminal objective. A Terminal objective is a more defined version of the learning goal. Both types of objective follows the format outlined below.

Writing Objectives

A learning objective is a description of an optimal performance learners are expected to be able to exhibit before they are considered competent in meeting the learning goal (Mager, 1962). Essentially, the goal describes the knowledge the learner is expected to obtain, while the objective describes how the learner will demonstrate that they have obtained that knowledge. Once learning goals are established, learning objectives that are directly associated with these specific outcomes should be built. Consider the following example of a misaligned learning outcome and learning objective proposed by Dick and Reiser (1989): “The learning goal is developing lifelong health habits and the associated learning objective is listing the major bones in the leg,”(p. 23). Although both the outcome and the objective both fall under the content area of Health and the Human Body, the listing of the major bones in the leg would not be an appropriate performance to assess whether or not learners would be able to develop lifelong health habits.

Mager (1984) proposes that there are three elements of a quality learning objective: performance, condition, and criterion. The performance is what the learner is expected to do or the result of the instruction. The condition describes the circumstances in which the performance should occur. The criterion establishes the minimum threshold of acceptable performance. Furthermore, an objective should clearly express an observable behavior that students are expected to perform in order to indicate achievement (Dick & Reiser, 1989). Orelove (1995), stated that when a goal includes the absence of performance on the part of a student it also lacks quality. For example, Johnny will sit quietly for 20 minutes or By the end of the course, students should know historically important dates in history (p. 4). Neither of these examples requires observable activity or quality performance on the part of the

students. In addition, neither goal is measurable. According to Benjamin Bloom. objectives should be measurable and serve to help create a structure for hierarchically classifying the measurability of learning objectives (Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, and Krathwohl, 1956; Anderson and Krathwohl 2001).

A simple way to craft learning objectives is to use the Heinrich, Molenda, Russell, and Smaldino’s (1996) ABCD format.

- Audience

- Behavior (Mager’s performance element)

- Condition (Mager’s condition element)

- Degree (Marger’s criterion element)

Heibrich et al. (1996) uses Mager’s (1984) three elements while adding the audience. The audience as being the learner. Sometimes, the generic term “learner” or “student” can be used. It is a best practice to be specific as possible (Heibrich et all, 1996). For example, a 12th grade history students or English Composition I students.

Objective Builder

To assist in writing learning objectives, the University of Central Florida (UCF) has created an easy to use objective builder at https://cdl.ucf.edu/teach/resources/objective-builder-tool/ . This tool uses a modified version of Heibrich et all (1996) ABCD format. The audience and condition are flipped to yield a CABD format. This was done to improve readability. Objective builder offers three learning domains to choose the behavior: cognitive (thinking), affective (feeling), and psychomotor (doing). Each domain uses a specific framework along with associated measurable verbs. The audience, condition, and degree components are textboxes and are displayed once they are entered. At the end of one objective, more can be added. Copy the objectives into a learning management system or word document when completed. It is released open-source so this means it is free to host on your own website and edits can be made. More information is available at https://github.com/ucfopen/objective-builder.

Examples

Audience (A), Behavior (B), Condition (C), and Degree of Mastery (D).

Learning objective written in the cognitive domain at the understanding level of Anderson and Krathwohl Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain.

- Given a blank map of the United States a fifth grade social student will identify all 50 states and capitals with 90 percent accuracy

Learning objective written in the affective domain at valuing level of the Krathwohl and Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Affective Domain

- Given a group project, the group members will seek input from everyone throughout the entire project.

Learning objective written in the psychomotor domain at the guided response level of Simpson’s Taxonomy of the Psychomotor Domain

- Given pizza ingredients, the employee will assemble a pizza in less than 10 minutes.

Terminal objective example

- When provided a plot, pacing, and the frequency of stunts, the learner will be able to classify the movie into a specific genre within two attempts.

Enabling objective example

- When given a movie scene, the learner will determine how many stunts occurred within two attempts.

References:

Anderson, L. W., and Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Bloom, B.S. (Ed.). Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Co

Inc.

Brown, A., & Green, T. (2006). The essentials of instructional design: Connecting fundamental principles with process and practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Dick, W., & Reiser, R. A. (1989). Planning effective instruction. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall.

Heinrich, R., Molenda, M., Russell, J.D., & Smaldino, S.E. (1996). Instructional Media and Technologies for Learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Merrill.

Mager, R. (1962). Preparing instructional objectives (1st ed.). Palo Alto, Calif., Fearon Publishers.

Mager, R. (1984). Preparing instructional objectives (2nd ed.). S.l.: Lake Pub.

Orelove, F., “Consider the potato.” Four Runner, Newsletter of the Severe Disabilities Technical Assistance Center, February, 1995.

Rossett, A. (1987). Training needs assessment. New Jersey: Educational Technology Publications.

Seels, B. & Glasgow, Z. (1998). Making instructional design decisions (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Smith, P. L., & Ragan, T. J. (2005). Instructional design (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Source:

This work, “Analysis: The Learning Task” is a derivative of the following works:

- “Robert Gagné and the Systematic Design of Instruction” by John H. Curry, Sacha Johnson, & Rebeca Peacock isused under a Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 license.

- “Considerations for Task Analysis Methods and Rapid E-Learning Development Techniques” by Ismail Ipek and Ömer Faruk Sözcü is used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- “Writing Measurable Learning Objectives to Aid Successful Online Course Development” by John Raible, Luke Bennett, and Kathleen Bastedo is used under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareALike 4.0 International License.

- Teaching in a Digital Age by Anthony William (Tony) Bates is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

“Analysis: The Learning Task” is licensed under licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareALike NonCommercial International 4.0 license by John Raible.