Unit 8: The Return Migration of the Crimean Tatars from Soviet Exile to Their Homeland

Section 1: The historical context of the deportation and return of Crimean Tatars

1.1 Why did the deportation of the Crimean Tatars seem irreversible?

The Crimean Tatars were deported in 1944 by the Soviet authorities.

Unlike other peoples exiled by the Soviet authorities before, during, and after World War II, Crimean Tatars were not granted the right to restore their national autonomy and return to their homeland after Stalin’s death.

This meant that their expulsion became indefinite.

Granted full freedom of movement within the USSR after 1956, Crimean Tatars were still prohibited from residing in Crimea.

In 1968, this situation led the historian Chantal Lemercier-Quelguejay, (in The Tatars of the Crimea, A Retrospective Summary) to conclude:

“In the circumstances, the Crimean Tatars are doomed to be assimilated by the peoples among whom they are now living. Thus, a people with a long glorious and tragic past will disappear finally from history.”[1]

Stuart Hall, a British sociologist of Jamaican descent who identified himself as a migrant, wrote in 1987 that migrants “…know that really, in the deep sense, she/he’s never going back. Migration is a one way trip. There is no ‘home’ to go back to.”[2]

1.2 What makes the story of the Crimean Tatars unique?

The Soviet authorities expected that the Crimean Tatars would assimilate and dissolve among other peoples.

Despite this, the Crimean Tatars:

- maintained their connection with their lost homeland;

- organized a powerful opposition movement;

- developed ideas of return rooted in collective memory, narratives of the past, and home-related practices;

- many attempted to return despite bans and restrictions;

- ultimately succeeded in returning home.

1.3 What is the historical context to the deportation?

Definition

Deportation – The state-enforced removal of individuals from a country.

Deportation is a legal and coercive process through which a government expels non-citizens or undesirable populations.

N.B. In the context of Soviet forced resettlements, deportations were used not to expel people across national borders, but rather to forcibly relocate entire populations within the country – from their native regions to remote or strategically chosen areas – often under conditions of surveillance and restricted rights.

The deportation of the Crimean Tatars started early in the morning on May 18th, 1944.

Bursting into the homes of Crimean Tatars, NKVD soldiers woke children and their parents without any explanation, giving them only a limited time to gather their belongings. Children, women, and the elderly were taken to railway stations where they were loaded into cattle cars.

Without proper sanitary provision, food, or even medical care in the overcrowded cars, the entire Crimean Tatar population was forced to endure a several-week journey into exile.

The total number of exiled Crimean Tatars was 207,111.[3]

Their final destinations were Uzbekistan and labor camps in the Ural region.

The entire nation was put into penal camps, so-called ‘special settlements’, with no right to leave.

The first years of exile were marked by high death tolls caused by starvation, diseases, and acts of oppression committed by the authorities.

After the eviction of Crimean Tatars in 1944, the Crimean Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic was transformed into a region.

Crimean Tatar names were replaced, and their mosques were destroyed.

As Norman Naimark puts it, the reason behind the deportation was “to fulfill a goal of Russian statesmen ever since the incorporation of the Crimea into the Russian Empire during the reign of Catherine the Great: Crimea without Crimean Tatars.”[4]

Crimea lost all traces of its indigenous people and became Russified in the aftermath of the deportation.

1.4 How did the situation of the Crimean Tatars change in the next three decades?

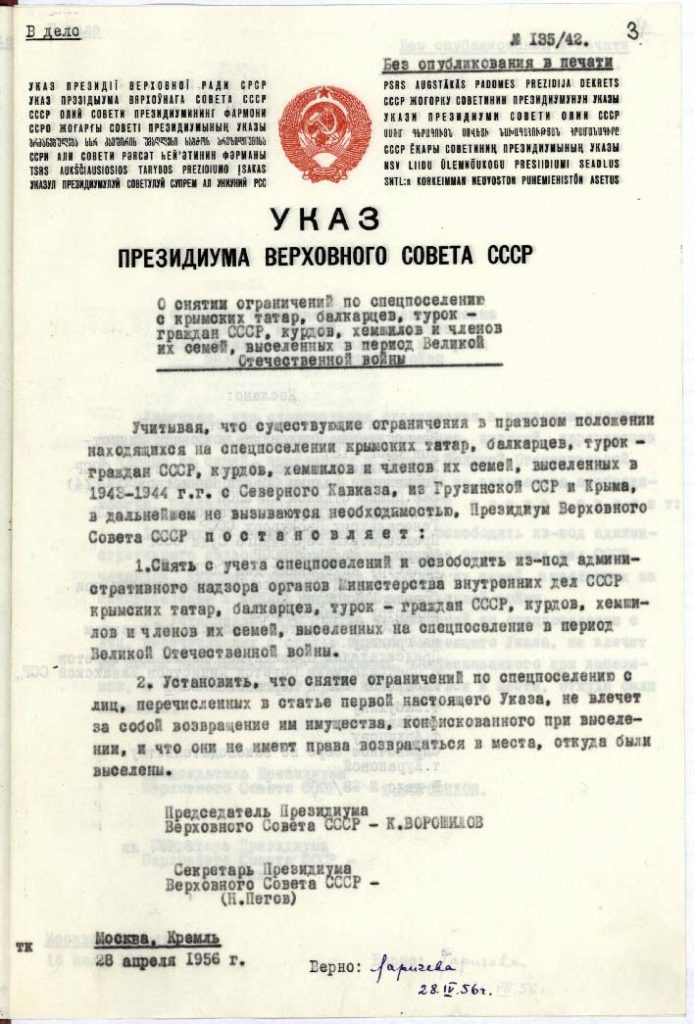

In 1956, a decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the USSR released Crimean Tatars from special settlements and allowed them to choose a place of residence freely.

However, they were banned from settling in the Crimean region.

Unlike other peoples deported by Soviet authorities, the Crimean Tatars – along with the Meskhetian Turks – were deprived of the right to restore autonomy and the opportunity to return to their homeland.

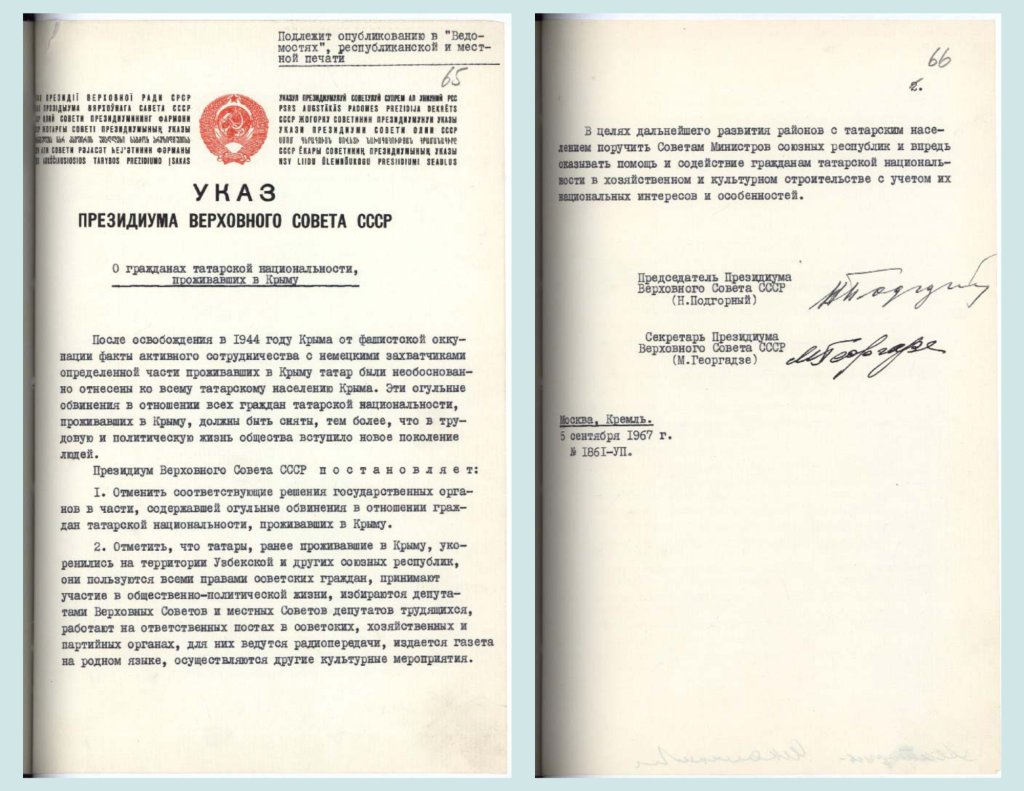

In 1967, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree according to which Crimean Tatars were rehabilitated.

They were still not allowed to return to their homeland.

It was the 1967 Decree that inspired Crimean Tatars to relocate to Crimea.

Between 1967 and 1978, about 10,000 Crimean Tatars managed to return to their homeland despite the ban.[5]

The growing number of returnees provoked a strong reaction from the Soviet authorities. In 1978, the “Resolution of the Council of Ministers of the USSR” suspended the return process for almost a decade.

1.5 What happened with perestroika?

Definition

Perestroika – The movement for reforms and liberalization of all spheres of life in the Soviet Union.

The Tatars’ migration back to Crimea resumed in 1987.

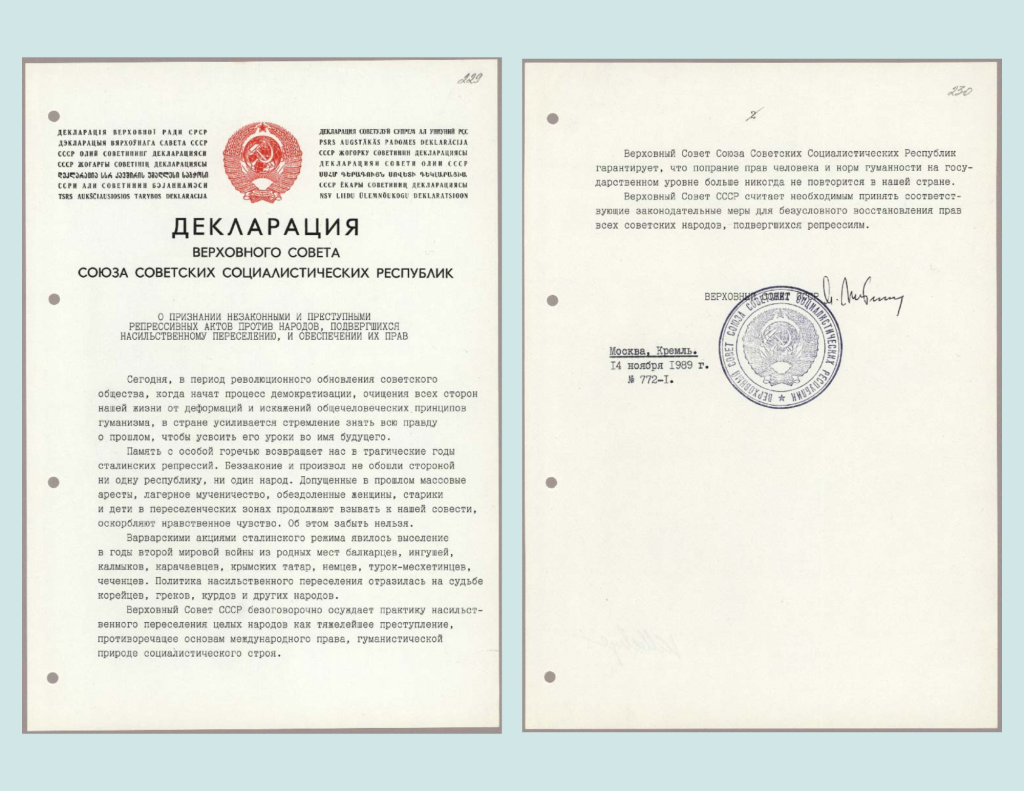

On November 14th, the Supreme Council of the USSR declared its intention to restore the rights of repressed peoples by law. It approved the summary of the state commission on the problems of Crimean Tatars on the 28th.

The document recognized the right of the Crimean Tatar people to return to their historical homeland and restore national integrity.

Central government thereby legitimized their right to return, prompting the start of a mass repatriation process.

According to statistics, in the late 1980s, the Crimean Tatar population in Crimea significantly increased:

| Year | Increase in Crimean Population[6] |

| 1988: | 17,500 |

| 1989: | 38,300 |

| 1990: | 83,100 |

A survey of 484 respondents conducted in 2003 indicated that the majority (66.9%) of Crimean Tatars returned home between 1989 and 1994.[7]

1.6 Review

Exercise 8.1

To check your understanding of this first section, answer the following questions:

- Why did the deportation of the Crimean Tatars seem irrevocable?

- How did the Crimean Tatars maintain their intention to return?

- What was the situation of the Crimean Tatars in 1944?

- What moves were taken by the Soviet authorities to prevent any return?

- How did the status of the Crimean Tatars change over time?

- What circumstances led to the return of the Crimean Tatars?

You have now completed Section 1 of Unit 8. Up next is Section 2: Key concepts in the study of return migration

- Lemercier Quelquejay, “The Tatars of the Crimea, A Retrospective Summary,” Central Asia Review 16, no. 1 (1968): 25. ↵

- Stuart Hall, “Minimal Selves,” in Identity: The Real Me. Post-Modernism and the Question of Identity, ed. Homi K. Bhabha and Lisa Appignanesi (London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1987), 44. ↵

- Oleksandr Gladun et al., “Otsinka demografichnykh vtrat krymskotatarskoho narodu vnaslidok deportatsiyi 1944 roku,” Demohrafiya ta sotsialna ekonomika 2 (2017): 20. ↵

- Norman M. Naimark, Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 103. ↵

- Oleg Bazhan, ed., Krymski tatary, 1944–1994: Statti, dokumenty, svidchennia (Kyiv: Ridnyi krai, 1995), 240–241. ↵

- Mihail Guboglo and Svetlana Chervonnaya, Krymskotatarskoe natsional’noe dvizhenie, vol. 1 (Moscow: CIMO, 1992), 153. ↵

- Idil P. Izmirli, “Return to the Golden Cradle: Post-Return Dynamics and Resettlement Angst among the Crimean Tatars,” in Migration, Homeland and Belonging in Eurasia, ed. Cynthia Buckley, Blair Ruble, and Erin Trouth Hofmann (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2008), 236. ↵