Unit 8: The Return Migration of the Crimean Tatars from Soviet Exile to Their Homeland

Section 3: Practices of Return

In this final section, we ask the questions:

- To what extent is return possible?

- What is the nature of that return?

3.1 How did the return of the Crimean Tatars take place?

After 1956, a Crimean Tatar national movement emerged, aimed at demanding state-organized mass return to Crimea and the restoration of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

This movement engaged in nonviolent resistance, with nearly the entire community participating.

As a result of a large-scale petition campaign, a decree was issued in 1967 that officially rehabilitated the Crimean Tatars.

However, it later emerged that on the same day, another resolution was also passed, which still prohibited Crimean Tatars from returning to their homeland.

Despite this, thousands of Crimean Tatars embarked on a journey into uncertainty – accompanied by the elderly who dreamed of dying in their native land and children who had never seen Crimea but had inherited the dream of it from their parents.

3.2 What is meant by ‘Front door return’?

The returnees would first arrive in Simferopol, the administrative center of the Crimean oblast, and immediately seek to claim their right to live in their homeland.

The parks and squares of the city were quickly occupied by groups of protesting Crimean Tatars, all waiting for an appointment with local authorities to seek some form of legal clarification.

As they were not allowed to book hotel rooms, the streets of Simferopol became their temporary home.

The human rights activist Petro Grigorenko, who visited Crimea in the summer of 1968, later recalled in his memoirs that the train station, airport, and city squares were filled with Crimean Tatars who “besieged” both Soviet and local party authorities. Grigorenko specifically noted that Crimean Tatar families, many with small children in tow, were often forced to sleep on the open ground in various public spaces.[1]

This strategy of return, ‘through the front door’, represented a form of direct action that lasted for about a year.

During this time, only 111 Crimean Tatars were granted permits allowing them to return to the peninsula.

For the others, however, it quickly became clear that they were not welcome in Crimea.

3.3 What is meant by ‘Back door return’?

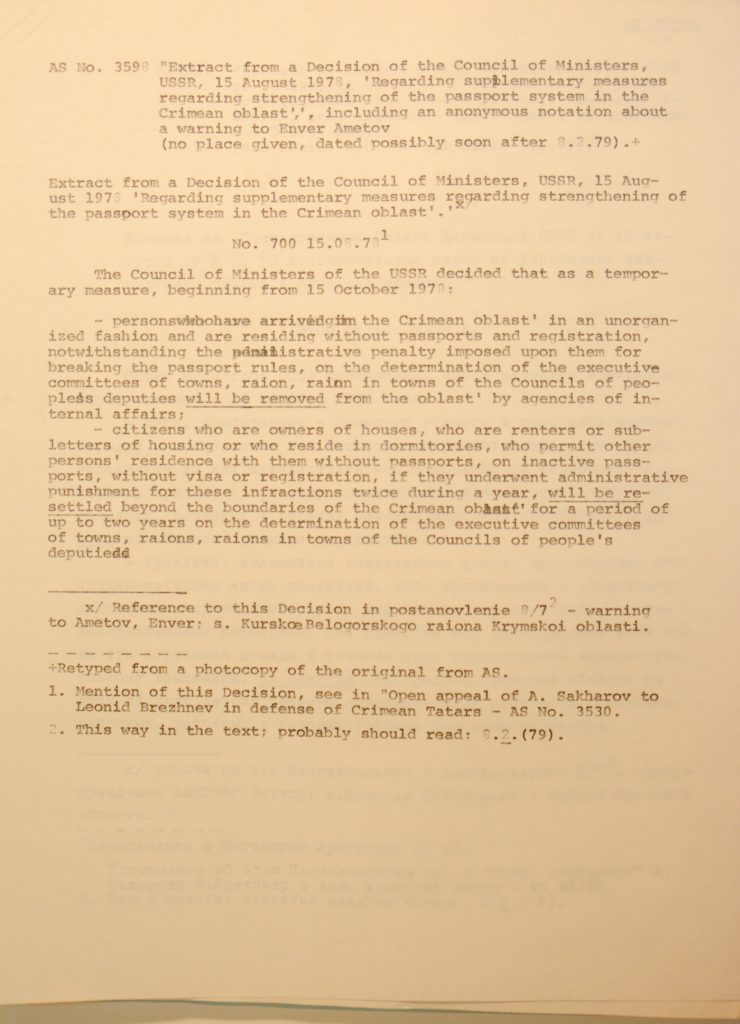

According to a resolution issued in 1967, Crimean Tatars were permitted to live anywhere within the Soviet Union, but only “in accordance with current legislation on the employment and passport regime.”

In practice, this meant that newcomers had to register for a residence permit, which required them to have a job. However, without registration, they could not apply for employment in the area they wanted to live. This vicious circle had been deliberately created to prevent Crimean Tatars from returning to their homeland.

Despite this, many sought to circumvent the restrictions by heading to smaller villages in the northern steppe region of Crimea, where they had a better chance of receiving a permit from local authorities or, at the very least, remaining unnoticed.[2]

In addition to creating obstacles for obtaining a residence permit, which was also required to purchase property, the authorities resorted to forced evictions.

Police raids against Crimean Tatars were typically conducted in the middle of the night, with officers forcing open doors and windows, dragging residents – including women and children – into waiting vans, and beating and restraining the men.

Once again, like in 1944, there was no opportunity to collect personal belongings, and valuables were often stolen by the officers. An evicted family might even find themselves abandoned at an empty railway station in the middle of the steppe, without any money.

These forced removals served as a form of re-traumatization, evoking memories of the 1944 deportations for the older generation, and came to be known as ‘repeated deportation’.

Nevertheless, this new wave of evictions from Crimea did not stop the Crimean Tatars from attempting to return, with some families being forcibly removed three or more times.

Example

Abdripi,[3] interviewed by the author, recalls that when his family returned to Crimea in 1969, they were forcibly evicted from the peninsula within a month.

After saving enough money, they made a second attempt to return in 1975, but his father was again accused of violating the passport regime and ordered to leave. He evaded deportation by hiding in the family home’s closet every time the local police came to check.

Not all those evicted from the peninsula succeeded in their efforts to return. As a result of these forced removals, many Crimean Tatars began to form diaspora communities in the neighboring Kherson and Krasnodar regions.

These new areas, where the evicted Crimean Tatars settled, became places of transit or liminal spaces, situated between exile and homeland.

The back door return practice did not guarantee registration or protection against eviction. However, some Crimean Tatars did manage to purchase a house, register themselves, and find employment.

Although the situation of the Crimean Tatars remained unchanged after 1967 (they were still prohibited from settling in Crimea), many of them nevertheless made the journey there.

This return, despite the adverse conditions and the continued ban, serves as evidence of the realization of the exile ideology.

York Public Library. Manuscripts and Archives Division. Edward Allworth papers. Series II. Crimean Tatars files, 1944–1994. Box 5. Folder 4. Articles and reports for research.

Between 1967 and 1978, approximately 10,000 Crimean Tatars managed to obtain residence registration in Crimea.

However, in 1978, the Soviet authorities introduced even stricter measures to curb their return from exile. As a result, reverse migration came to a halt for nearly a decade, resuming only during Perestroika.

The mass repatriation of Crimean Tatars in the late 1980s and early 1990s was, to some extent, a response to the government’s inaction. Its rhetoric on democratization and glasnost stood in stark contrast to the continued discrimination and restrictions imposed on Crimean Tatars.

Exercise 8.3

- Explain what is meant by ‘front door’ and ‘back door’ return.

- List the obstacles Soviet authorities created for Crimean Tatars on their way home.

3.4 To what extent is return possible?

Return is not an event but a long journey toward restoring normality lost after the 1944 deportation.

Its endpoint is not always physical arrival; rather, it involves a process of emplacement – redefining home and homeland in the present, as returning to the past is impossible.

As Stuart Hall aptly put it, “There is no ‘home’ to go back to.”[4]

If deportation – an unjust act of punishment – disrupted normalcy, return aimed to restore life’s harmony.

Memoirs of Crimean Tatars emphasize the process of rooting in the homeland and ‘rediscovering’ it after return.

Ultimately, return is also a form of migration or, as Crimean Tatars describe it, another resettlement.

For the second generation of Crimean Tatars born in exile, returning to Crimea was both a first encounter with their homeland and a realization of the gap between their parents’ idealized stories and reality.

For early returnees, the experience was far from idyllic. The harsh realities of a promised land and the daily struggle for rights brought new challenges.

Example

Ediye,[5] who returned with her parents as a child in the 1960s, expected something different – certainly not the dry steppe of northern Crimea.

“I remember we took a bus from Simferopol to Kerch, and I asked my father, “Daddy, where is Crimea?” He gestured around and said, “Look, it’s everywhere.” I looked out the window, but all I saw was the steppe.

So I asked again, “Daddy, where is Crimea?” To be honest, I was shocked. We had lived quite well in Uzbekistan – my father had built us a new house. But in Crimea, the water from our well was bitter.”

Returns can bring confusion and frustration as dreams collide with reality.

Example

Shefika[6] recalls that, based on her parents’ stories, she had imagined Crimea as a promised land, but when she arrived, she thought, “…nothing special. Simferopol was just a large village.”

Even for those born in Crimea before the deportation, expectations often clashed with reality. Lutfi, for instance, remembers the pain of seeing orchards cut down after the deportation.

As noted earlier, return involves reinventing the homeland – reconstructing it for those born in Crimea and constructing it for those born in exile.

For the second generation, the stark contrast between their parents’ stories of a ‘dream land’ and the reality they encountered shaped this reinvention, just as it did for those who had lived in Crimea before 1944.

The return of the Crimean Tatars was not an event but a prolonged process that required adaptation to new conditions and the restoration of harmony through practices rooted in memories of life before deportation.

Returning is not only the construction of the homeland, the invention of a new homeland to replace the lost one, but also the formation of one’s own identity on the way home.

Returning as a journey does not necessarily end with the arrival. It also contains emplacement.

By the 1990s, Crimea had been thoroughly Russified – demographically, politically, and culturally.

As Crimean Tatars returned from decades of exile, they were met with resistance from entrenched local elites who upheld Soviet-era hierarchies and opposed any meaningful redistribution of power or land.

Although the community mobilized politically, the Soviet and later post-Soviet authorities denied the restoration of Crimean Tatar national autonomy.

Without institutional recognition or resources to reclaim their collective rights, Crimean Tatars remained politically marginalized.

This continued absence of indigenous autonomy and underrepresentation contributed to the structural weakness of Crimea, creating conditions that ultimately facilitated Russia’s occupation of the peninsula in 2014.

Exercise 8.4

Having read the last part of section three on the possibility of return, give a summary of what you consider to be the 3 greatest obstacles to return. Explain your choices:

| Obstacle | Reason |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exercise 8.5

- ‘Mapping the Return’

- Research key locations related to Crimean Tatar exile and return.

- Identify major migration waves and obstacles faced at different stages.

- Use a digital tool (Google My Maps, StoryMapJS, or a simple infographic) to visualize routes, policies, and events.

- Write a short essay (500-700 words) on how return migration shaped Crimean Tatars’ identity and political activism.

- Letters from Exile (Creative Writing & Perspective-Taking)

- Choose a time period (e.g., late 1950s, early 1980s, or 1991).

- Write a first-person letter or diary entry (300-500 words) reflecting on:

- The struggles of life in exile.

- The decision to return and challenges encountered.

- Hopes and fears about reestablishing life in Crimea.

- Compare and contrast your narrative with others in small discussion groups.

- ‘Home, Lost and Found’ – Concept Mapping Activity

- Divide into small groups and use large sheets of paper or a digital concept-mapping tool.

- Brainstorm and visually map the changing meaning of “home” across three phases: exile, return, emplacement.

- Include social, emotional, legal, and spatial dimensions of home.

- Each group presents their map and discusses key findings with the class.

You have now completed Section 3 of Unit 1. Up next is a collection of resources and additional readings for this unit.

- Petro Grigorenko, V podpol’e mozhno vstretit’ tol’ko krys (New York: Detinets, 1981), 635. ↵

- Martin-Oleksandr Kisly, “Crimean Tatars’ Return to the Homeland in 1956–1989” (PhD diss., National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, 2021), 121. ↵

- Abdripi (1962), interview by author, August 2, 2015. ↵

- Hall, “Minimal Selves,” 44. ↵

- Ediye (1963), interview by author, August 12, 2015. ↵

- Shefika (1950), interview by author, January 9, 2014. ↵