Unit 1: The Ethical and Methodological Challenges of Research in times of War and Displacement

Section 1: Why do we need to be sensitive about language when carrying out research in wartime?

1.1 What language do we use to talk about war?

When we speak about society in times of war and displacement, we need to remember that we are not simply using definitions but also activating their semantic content specific to the current moment.

Accordingly, attention to the terminology/words used in describing conflict or displacement is not only a scientific but also a social responsibility of the researcher. The naming issue raises the following three questions:

(i) What language do we use in the research question?

First, we need to understand the nature of war and its naming.

The terminology and conceptual framework we then choose will significantly influence all stages of the study, from the formulation of the research question and design to the recommendation of practical steps.

In academic publications, these definitions dо not simply define the situation but denote a certain way of seeing events or affected groups.

(ii) What language do we use in the field?

Second, there is the issue of naming in the field phase of research.

Under conditions of war or the acute phase of conflict, people find themselves in different realities (social, informational, political etc.).

In the field phase, therefore, the researcher usually talks to the research participants with the words participants use to define their reality.

Errors in the choice of terms to describe reality can lead to participant non-cooperation, traumatization and/or jeopardize the safety of the researcher or participants.

(iii) What language do we use in the presentation of research results?

Third, in the presentation of research results the researcher is expected to ‘translate’ the language of the participants into the language of terminological apparatus.

This language is seemingly universal but is often embedded in a certain perspective. This perspective then inevitably becomes an expression of the author’s political position and power relations.

1.2 How do we categorize the displaced?

We also need to be sensitive about the ‘naming’ and ‘categorization’ of the displaced.

The annexation of territories following the outbreak of war and displacement of large population groups transforms the established landscape of social and national identities as well as hierarchies of belonging.

(i) What is the new category of ‘refugee’?

Peter Gatrell (1999) argues that the new category of ‘refugee’ created by war might suddenly become an important social category and a factor of identity.

War and displacement provoke discussions. The question of who belongs to ‘us’ causes anxieties and concerns that lie at the heart of national identity as well as transforming hierarchies of belonging (Sereda 2023).

For example, in discussions over cross-border displacement, some groups are seen as belonging more, and therefore as more deserving, than others.

When conducting research scholars should differentiate between categories:

- In everyday interactions used by the receiving community and by the displaced (because they might differ).

- Discursive/political definitions used in public debates and policymaking by politicians or media.

- Official definitions used in migration statistics – these are often legally defined and regulated categories.

- Analytical definitions used in academic research.

In some cases, the same word, for example ‘migrant’ or ‘refugee,’ could acquire very different meanings or the same group could be labelled differently in each context.

You will find more on the politicisation of labels and numbers in the unit The Possibilities, Limitations and Politicisation of Migration Data.

Example

by themselves: as ‘new people in the community,’

by politicians: as ‘migrants,’

legally: as ‘persons under a temporary protection scheme,’

analytically: as ‘refugees.’

When conducting research scholars often have to navigate between different audiences. They need to be sensitive to categories and the meanings, connotations, and ideological framing behind the terms used by themselves or by others.

(ii) Why is the term ‘migrant’ a misleading label?

The term ‘migrant’ is used to describe many phenomena. The key ones are:

- a person who moves from one place to another within the country (urban-rural migration, educational migration);

- a person who crosses a border, either voluntarily (for labour) or forcibly (as a refugee or person under temporary protection);

- a person who moves for short-term reasons (recreation, holiday, visits to friends and relatives, business, medical treatment or religious pilgrimage, or as circular labour migration);

- a person who moves for long-term reasons.

Official statistics put together in one category long-term migrants from all possible categories. This may include persons who have obtained citizenship in their new country (were naturalized) or those who belong to the second generation born in a country which does not grant citizenship by birth and are therefore still counted as immigrants in migration statistics.

Therefore, when in official documents or media reports, we use term ‘Ukrainian migrants’ or ‘Syrian migrants’ it remains unclear who is included – the old diaspora who arrived before either as labour, as political migrants or any other type of migration, or a new wave of war-induced displacement, or both.

In official documents and reports, we use the officially recognized terms ‘internally displaced persons’ for those who are displaced within the country, and ‘refugees’ (‘forcibly displaced’, ‘war-displaced’, ‘war-afflicted’ displacement) for those who cross the border.

However, for most Ukrainians seeking refuge outside the country after 2022, the term ‘refugee’ is misleading because it refers to asylum seekers. Ukrainian citizens remain under the Temporary Protection Directive or similar national protection schemes.

(iii) What stereotypes and labels exist in receiving communities?

Receiving communities might have their own labels charged with existing stereotypes.

Example

(iv) How do we categorize and name the displaced in research?

For the resettled in any country categorization and naming becomes a very sensitive issue, which impacts researcher-interlocutor interaction.

It later translates into the ethical issue: how do we reproduce the voice of research participants without jeopardizing their agency?

The media mostly present displaced people as people who are coping with the psychological consequences and humanitarian problems of resettlement. Many publications couple the term ‘IDPs’ or ‘refugees’ with ‘problems’ or ‘humanitarian issues.’

This contributes to the discursive fixation of the displaced as a powerless and victimized group

You will find more on media representations in the unit The Visual Politics of Migration: Constructing the Representation of Refugeehood and Displacement.

As a result, interlocutors often refuse to define themselves as ‘displaced persons’ because they do not want to be seen as disempowered victims.

Reports by international organizations on the impact of the war alert us to the general numbers of those affected, the number of internally displaced or those fleeing abroad.

However, these generalized numbers tell us little about the diversity of the displaced, who do not constitute a socially, politically, religiously, or ethnically homogeneous group, and the destinations they choose.

The displaced are often presented as a single group: as ‘Afghani refugees,’ ‘Syrian refugees,’ ‘Ukrainian refugees.’ Their ethnic, religious and linguistic composition may be very complex (Ukraine is a good example of such diversity).

Different groups may also receive distinct treatment in receiving countries. Therefore, research into the displaced should also account for diversity.

It is also important to stress the situation of research participants might radically change over time and with it their possible categorization too.

When analyzing migration, caution is needed when categorizing individuals or groups within the rigid binary of ‘voluntary’ versus ‘forced’ migration.

Data collected at a single point in time may fail to capture the full spectrum of experiences and the various stages migrants go through — departure, journey (including transit), arrival, settlement, return, onward migration, or re-immigration.

Depending on the stage or context (self-identification, academic analysis, or classification by immigration authorities), different labels may be more appropriate to describe a group’s or individual’s experience (Bivand & Oeppen 2018).

Example

an IDP,

a refugee under temporary protection,

a returnee,

an asylum seeker.

Scholars need to aim at describing the situation reflexively and sensitively.

1.3 Review

We have now come to the end of the first section in the unit. Look over Section 1 and do the following exercises.

Exercise 1.1

Now look over Section 1 and answer the following questions to check you have understood the key points:

- How does the choice of terminology (e.g., ‘refugee,’ ‘IDP,’ or ‘resettled’) used in academic research and official documents shape the perception of displaced individuals, both in the context of their identity and their agency?

- In what ways do the societal, political, and informational realities experienced by displaced individuals affect the interaction between researchers and participants?

- How can researchers adapt their methodologies to navigate these complexities sensitively and effectively?

- How can researchers ensure their language choices do not reinforce stereotypes or power imbalances?

Exercise 1.2

The following are extracts from interviews conducted between October 2014 and January 2015 as a part of the project “Contemporary Ukrainian Internally Displaced Persons: Main Causes, Resettlement Strategies and Adaptation Problems.”

Part of the interviews focused on exploring how the interlocutors would describe or name their group. This often sparked discussions about the terms used officially and the labels circulating in the media.

Read the interviews. NB. S = the scholar who carries out the interview; I: is the interlocutor/ person interviewed.

(If you would like to learn more, you can view additional information on the Contemporary Ukrainian Internally Displaced Persons project)

Interview: Kyiv_East_Male_middle-aged_Donetsk (conducted in Russian)

S: Well, if we are talking about terminology, what word or concept should be used correctly to call these people who were forced to move from Crimea, for example, to Ukraine or from Eastern Ukraine, from the territories where military actions are taking place, to Ukraine?

I: Probably, you can call them ‘refugees’. Because we are refugees after all. We ran away from the war. All these refugees, they are, in general, all different people. Some really were very well-off and for them, well, with some losses, they still did not encounter any problems when moving. Some had a little inconvenience, but in general kept their lifestyle, that’s how our family is. Some were completely left without everything, without a roof over his head, without money, without work, without… This, of course, is a completely different situation. One way or another, it is correct to call all of us refugees, but we ran away from wars.

S: But if we choose from the terminology, now they are talking about refugees, migrants, and internally displaced people. Which of the terms is the most correct in relation to them?

I: ‘Internally displaced’ is for me some kind of forced displacement, a person was taken and relocated. I, too, of course, did not want to go to Kyiv and leave, but no one forcibly took me out under a convoy in handcuffs.

S: Migrants?

I: Well, ‘migrant’ is a more neutral word. It usually means that a person lived, achieved something. One is not in such an extreme situation, one was simply not satisfied with something, one migrated, there, from one part of the country to another. I came to the capital for a better life. This is probably a migrant. And when, because of military actions, a person flees to peace, to a place where they are not shot, it seems to me that he is rather a refugee.

Interview: Kyiv_East_female_middle-aged_from Donetsk (conducted in Russian)

I: I would avoid using the status ‘displaced’, because ‘temporarily displaced’ implies an organized evacuation. As such, there was no evacuation. Once again, volunteers, not state officials, were involved in moving us. Therefore, we can say that these were people who temporarily left. Well, probably. To say that these are ‘refugees’ (bizhyntsi)? ‘Refugee’ is a legal term that Ukraine again does not accept, because it entails the assumption of obligations in relation to these refugees. Plus, there is something in the word refugee that humiliates a person and human dignity. That is, it is not pleasant to feel like a refugee. Therefore – ‘temporarily departed (vyiekhavshye)’. ‘Displaced’ – this may be correct in the philological sense. That is, they relocated people, right? But in fact, they left themselves.

Interview: Kyiv_East_female_young_from Donetsk (conducted in Russian)

I: I don’t like the term ‘displaced (pereseletsi)’. ‘Refugee’ is even more depressing. Although I understand that there is a ‘refugee’ category. These are people who have nowhere to live. They have no opportunity to organize their existence in a new place. And ‘displaced’ are those who moved more organized and independently. One moved, found a job and is doing what he did before. It seems to me that a more neutral word should be invented.

S: It doesn’t occur to me what it could be?

I: ‘Population from the ATO (Anti-Terrorist Operation) zone’ for example. But we say that they have moved, so it is necessary to give additional meaning – ‘moved from the ATO zone’ or ‘displaced from the ATO zone’ maybe?

Interview: Lviv_Crimea_Male_Old_Zarechnoe (conducted in Russian with Crimean Tatar)

I: The word ‘refugee (bizhenets)’, if the root of this word is considered, then I would not like this word to be applied to me, because I did not run away. A ‘refugee’ is one who ran away. I just decided to relocate (perevezty) my family, my children away from the trouble.

Interview: Kherson_Crimea_Male_Middle Age_ Simferopol (conducted in Ukrainian with Crimean Tatar)

I: I consider myself a ‘displaced person (pereselentsem)’.

S: Why?

I: It is temporary.

S: What is the difference between a ‘refugee’ and a ‘temporarily displaced’ person?

I: The ‘refugee’ – is the one who fled, and I am going to return.

Kherson_Crimea_Male_Young_ Ivanivka (conducted in Ukrainian)

I: The displaced from Donbas I would call: ‘those who escaped from war.’

Now carry out the following steps based on what you have read:

Step 1: Look through the interviews and make a list of the labels used by the respondents.

Step 2: For each label used by multiple respondents, give the explanations and sentiments they connect with the label:

- How does the choice of terminology impact their self-perception?

- Are there any variations between respondents?

- If so, what are the reasons behind these differences?

Step 3: Pay attention to any alternative terms proposed by the interlocutors.

- Are similar alternatives suggested by multiple individuals?

- How do their descriptions of these alternatives compare?

Step 4: Can you suggest 2–3 umbrella terms that better reflect the experiences of the interlocutors? Why are these terms more neutral or appropriate?

Exercise 1.3

In this pair work exercise we use the same description or situation from the lives of a migrant but written in different words.

For example:

(A) ‘A refugee from the war in Ukraine is looking for a job.’

(B) ‘A migrant from Ukraine is taking our jobs.’

Student A will receive description (A); student B description (B).

Objective: To investigate how the choice of terminology affects the perception of people who were forced to leave their homes because of the war and found temporary shelter in Ternopil.

You will receive one of three scenarios of the situation, each of which uses different terminology:

- ‘Refugee’

- ‘Internally Displaced Person’ (IDP)

- ‘Immigrant’

Your partner will receive a different version of the text. After reading your versions, discuss your impressions and associations.

Scenario 1: ‘Refugee’

Olexander, a Ukrainian refugee, fled Berdyansk in March 2022 after the city was occupied. He left in a panic, leaving everything behind — his home, his job, even his elderly mother, because she could not go with him. In Ternopil, he tries to find housing and work but faces indifference from the locals. He is often perceived as a burden on the social system, and he feels that here he is seen not as a person, but as another ‘refugee’ who must be ‘tolerated’.

- What emotions does the word ‘refugee’ evoke?

- Does this word sound like something temporary or permanent?

- How do you think Oleksandr feels in this status?

Scenario 2: ‘Internally displaced person’

Oleksandr, an internally displaced person, came to Ternopil after being forced to leave his native Berdyansk due to the war. He still feels a strong connection to his home, even though he is in another city, and dreams of returning as soon as it becomes possible. He faces challenges – finding a job, adapting to a new environment, constant thoughts of returning. It is difficult for him to arrange his life, because even in official documents he is called ‘displaced’, as if his life is suspended between two worlds – he is no longer at home, but not in a new home.

- Does the word ‘displaced person’ change your perception of the situation?

- Does this status seem less dramatic than ‘refugee’?

Scenario 3: ‘Immigrant’

Olexander, a Ukrainian immigrant, starts his new life in Ternopil after the war forced him to leave Berdyansk. He actively looks for work, attends local events, and meets new people. He feels part of society, although sometimes it seems to him that his past life has remained in another reality. He is called ‘immigrant’, as if he has started a completely new chapter, although he himself does not yet know if this is really so.

- How does the word ‘immigrant’ change your perception of Oleksandr’s situation?

- Is it perceived as less dramatic than ‘refugee’?

- Does it convey more of an active position or a passive status?

Discussion and Conclusions

After working through the three scenarios, compare your impressions. Do you agree with the following:

- ‘Refugee’ evokes the most sympathy, but also the greatest association with helplessness and dependence on help.

- ‘Internally displaced person’ is perceived less emotionally but emphasizes the uncertainty and complexity of living between two worlds.

- ‘Displaced person’ creates an image of a person who takes control of their life but may downplay their losses and difficulties of adaptation.

Exercise 1.4

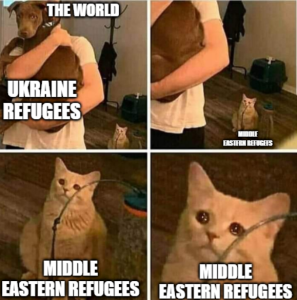

Look at the two memes below—one reflecting an internal Ukrainian perspective on displaced people (IDPs); the other representing an external view (from international sources).

Now answer the following questions:

- What two situations are being mocked?

- What events, behaviors, or stereotypes are the memes commenting on?

- Are they critical, supportive, or neutral?

- Comment on the division between ‘us’ and ‘them’.

- Does this division change between the internal and external perspectives?

- Are the memes humorous, sarcastic, or offensive?

- Do they evoke empathy, criticism, or confirm stereotypes?

Reflect on broader trends:

- Have you come across other memes about Ukrainian IDPs or refugees?

- What themes or recurring messages do you notice in such memes? (e.g., solidarity, resentment, victimhood, heroism, dependency)

- How do these memes shape public perception of displaced people?

- Who reproduces them – international media, activists, or foreign public, Ukrainian displaced persons or other groups?

- If possible, provide a link or screenshot of those memes.

Write a 500-800 word response, using specific examples from the memes. If you analyze additional memes, include screenshots or links to them. Cite any sources if you reference outside research.

You have now completed Section 1 of Unit 1. Up next is Section 2: Quantitative studies of displacement at times of war.