Unit 2: The Visual Politics of Migration: Constructing the Representation of Refugeehood and Displacement

Section 1: What do we mean by the visual politics of migration?

1.1 What is at stake?

A recent UN Refugee Agency report indicates that the number of forcibly displaced people in the world reached a record 122.6 million in 2024, of whom more than 43 million are refugees [1]. Among these are 6.8 million refugees from Ukraine recorded globally [2].

This unprecedented level of displacement is driven by a combination of factors, including:

- climate change,

- ongoing conflicts,

- political instability,

- economic inequality in various regions.

These dynamics highlight the critical need to examine how migration and displacement are represented and understood worldwide.

One crucial aspect of contemporary migration studies is the analysis of its visual representation in media, political communication, and the visual and performative arts.

Since the publication of the seminal work A Seventh Man by Berger and Mohr (1975), which combined images and poetic narratives to explore labor migration, there has been a sustained interest in developing methodologies to analyze the visual imagery of migration and displacement.

1.2 What is the ‘visual turn’?

The ‘visual turn’ (Mitchel 1994, Gottfried and Mitchell 2009) in the humanities and social sciences has further reinforced the importance of studying how migration is framed through images. Visual narratives shape public perception, influence policy debates, and construct social identities.

Visual methodologies open up new possibilities for understanding migration. They raise theoretical and ethical questions about:

- creating and sharing images;

- the objectivity and subjectivity of representation;

- the power dynamics involved in visual storytelling (Kunz et al. 2021).

In recent decades, media and art have emerged as powerful tools in shaping perceptions, constructing narratives, and influencing public discourse on migration. Malkki (1996) identifies media imagery of refugees as “a key vehicle in the elaboration of a transnational social imagination of refugeeness” (234).

Beyond traditional media portrayals, Ball (2021, 285-286) argues that other visual modes – such as diagrams, maps, films, video diaries, collages, street art, and sculptures – play an equally significant role in shaping public understandings of migration, offering new perspectives on the lived experiences of displaced individuals.

1.3 How do visual-centric media influence public discourse?

“We live in a visual age … Images surround everything we do. This omnipresence of images is political and has changed fundamentally how we live and interact in today’s world” (Bleiker 2018).

Digital media, saturated with visuals, have become a powerful tool that shapes public discourse and our individual perceptions. The visual-centric media platforms also have redefined how we perceive and understand conflicts, humanitarian crises, and migration.

The aesthetic and performance parameters of the platforms, underpinned by algorithmic mechanisms, amplify specific narratives, reinforce pre-existing biases and prioritize certain types of engagement, provoking strong emotional reactions.

The rapid circulation of images of displacement and suffering embeds them in larger political discourses, influencing policy debates and humanitarian responses.

As a result, many recent studies focus their attention on:

- the use and misuse of such images;

- how they are framed by different actors;

- the ethical implications of their dissemination;

- their role in shaping public perceptions of migrants and refugees.

1.4 How are refugees portrayed in visual media?

The portrayal of refugees in visual media holds the potential to either cultivate empathy and solidarity or reinforce stereotypes and discrimination (Bleiker et al. 2013; Chouliaraki and Stolic 2017).

Often, media and political actors employ specific visual symbols and metaphors to frame migration as “an alarming situation beyond the control of the majority community,” adopting urgent tones and cinematic codes that depict migration as a physical and societal threat to the dominant community’s ethos (Swadesh and Hooda 2024).

A prominent example of visual tropes in migration representation is the recurring depiction of migration as a ‘flow’ or a ‘wave’. Such imagery often portrays migrants as a faceless mass, with photographs taken from a distance that prevent eye contact or individual recognition. This aesthetic choice reinforces narratives of migration as an overwhelming, impersonal phenomenon beyond the control of the state actors.

Example

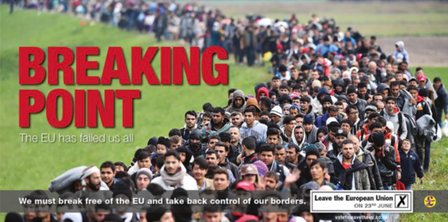

A striking case of such visual framing is Jeff Mitchell’s widely circulated photograph of fleeing refugees from the zones of conflict toward Europe. It was taken in Slovenia in October 2015 (Fig. 2.1). Originally, Mitchell captured this image to “tell the story of the migrants” and document their difficult journey to a safer life in Europe (Beaumont-Thomas 2016).

The photograph was later repurposed for political messaging in several European countries, with completely different framings that transformed its meaning.

Exercise 2.1

Look at the two photographs below. The photo on the left is a campaign poster from the UK Independence Party (UKIP) in 2016. The photo on the right was used by the right-wing French politician Eric Zemmour in his 2022 campaign.

- What is the purpose of UKIP’s use of the photograph in their campaign poster?

- What narratives does it reinforce?

- What is the purpose of the juxtaposition of peaceful French villages with Mitchell’s photograph?

Other recurring visuals of migration used in political discourse include:

- imagery of overcrowded boats carrying refugees across the Mediterranean;

- barbed wire fences symbolizing fortified borders;

- large groups of people at border crossings;

- veiled women or men hiding their faces, which plays into cultural and security anxieties.

These representations often lack nuance and dehumanize migrants, reducing them to abstract symbols of crisis rather than individuals with their identities and unique stories and experiences. They reduce migrants to an undifferentiated mass or render them unidentifiable, making it easier to manipulate the interpretation of these images to fit a specific political agenda.

The use of such imagery in political campaigns inevitably reinforces perceptions of migrants as a threatening “other”, evoking fear and deepening social divisions.

Exercise 2.2

You can find further examples of visual tropes of migration in:

- Doerr, Nicole. “Visual Tropes of Migration Tell Predictable but Misleading Stories.” The Conversation, 2018. https://theconversation.com/visual-tropes-of-migration-tell-predictable-but-misleading-stories-106121.

You can read more on this topic in the following works:

- Doerr, Nicole. “How Right-Wing Versus Cosmopolitan Political Actors Mobilize and Translate Images of Immigrants in Transnational Contexts.” Visual Communication 16, no. 3 (2017): 315-336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357217702850.

- Héois, Aurélie, and Bérengère Lafiandra. “Multimodal Representations of Motion in Cartoons on Immigration: The Case of France and the US.” Metaphorik.de, 2023, Multimodal Tropes in Contemporary Corpora, 34. https://hal.science/hal-04566404f.

1.5 Can visual media challenge dominant narratives of migration?

The representations we discussed in the previous sub-section (1.3) reinforce stereotypes and negative perceptions. However, visual media also have the transformative capacity to humanize displaced individuals and challenge dominant political narratives.

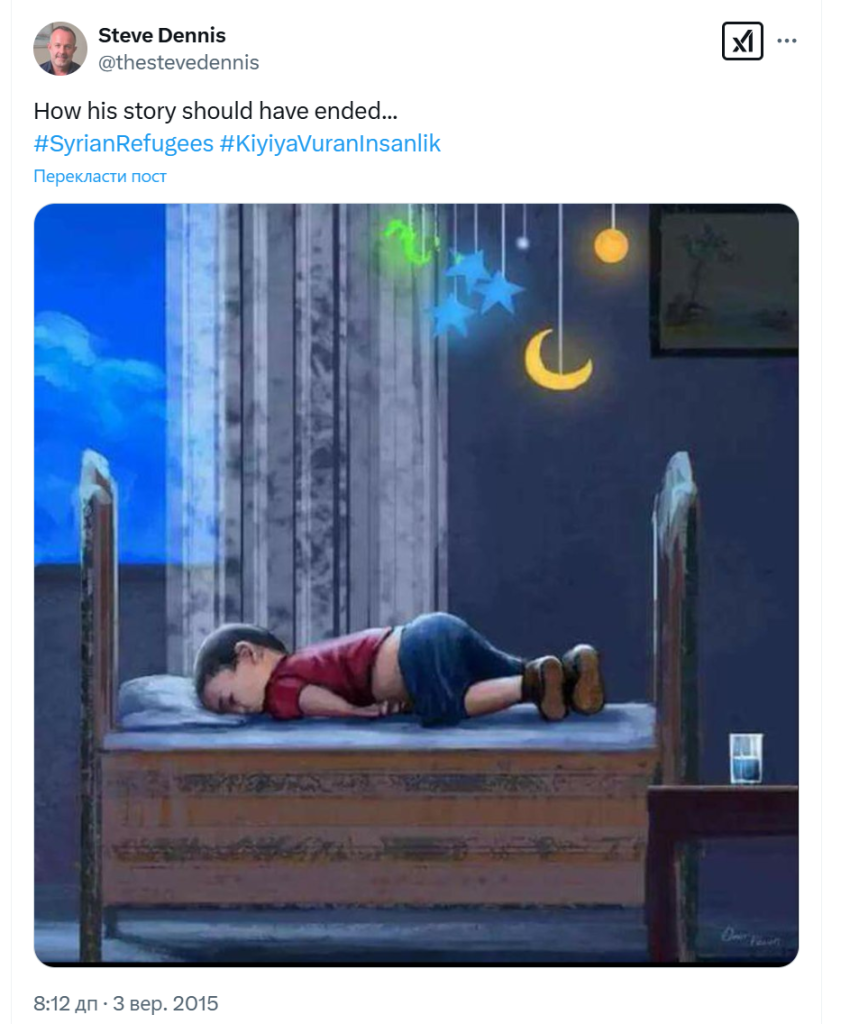

A powerful example is the iconic photograph of Alan Kurdi, a young Syrian boy who drowned in the Mediterranean Sea on September 2, 2015 (Fig. 2.4).

His lifeless body, in a red T-shirt, blue shorts, and small shoes, was found washed ashore on a Turkish beach near Bodrum. The image, captured by Turkish photojournalist Nilüfer Demir, shows the toddler lying face-down in the sand, his arms resting by his sides as gentle waves lap at his fragile body. The stark contrast between the child’s small, motionless body and the vastness of the sea vividly encapsulated the human cost of forced displacement, transforming the image into a powerful symbol of the refugee crisis.

As the journalist Joel Gunter noted, “the picture has in some way changed, rather than just documented, the refugee crisis unfolding into Europe” (Gunter 2015) [3]

The photograph quickly went viral, sparking international reactions and led to renewed calls for policy change, greater humanitarian aid, and a shift in public discourse surrounding refugees. Thousands of people rallied to support refugees, donating money, supplies, and even offering their homes to those in need. Charities and aid organizations saw a surge in donations, reporting unprecedented levels of public engagement (Henley et al. 2015)[4]

The wide mediatization of the photo also shifted the media representation and political discourse on refugees in Europe. Papers switched their wording of the asylum-seekers from economic ‘migrants’ to ‘refugees’ fleeing from war and persecution (Hussein 2020).[5]

The image of Alan Kurdi resonated deeply with artists worldwide, inspiring numerous artistic responses. Street artists, painters, and illustrators recreated the photograph in murals, digital art, and installations, transforming it into a symbol of collective mourning and a call for action.

Example

One notable example is a mural created by artists Justus Becker and Bobby Borderline in Frankfurt, Germany (2016) (Fig. 2.5). This 120-square-meter mural, conceived as “a memorial piece representing all children who died fleeing from war to Europe,” reproduced the iconic photograph of Alain, serving as a sad reminder of the tragic event and its lasting impact.

Other artists reimagined the scene by juxtaposing it to the images of happy, non-refugee children, or incorporated political personalities or symbols of EU power institutions, childhood motifs such as toys and lullabies, or universal emblems of innocence like angel wings.

These artistic appropriations not only reinforced the emotional weight of the original image but also framed it within a broader socio-political context, highlighting issues of displacement and global responsibility.

Exercise 2.3

Look at Figure 2.6 which shows an artwork by Steve Dennis, first published on Twitter on September 3, 2015, and since shared 25 billion times.

- What mood and environment does Dennis’s work portray?

- What has the artist preserved from the original photograph?

- How does Dennis recontextualize the original image’s impact?

- In what sense is this an example of a counter narrative?

Exercise 2.4

You can find more examples of artworks inspired by Alan Kurdi photograph in:

- Reflections on the Image of Alan Kurdi, by David Levi Strauss

Read in more detail about the artistic construction and contestation of Alan Kurdi’s iconic imagery in:

- Mortensen, Mette. “Constructing, Confirming, and Contesting Icons: The Alan Kurdi Imagery Appropriated by #HumanityWashedAshore, Ai Weiwei, and Charlie Hebdo.” Media, Culture & Society 39, no. 8 (2017): 1142–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717725572

- Geboers, Marloes. “‘Writing’ Oneself into Tragedy: Visual User Practices and Spectatorship of the Alan Kurdi Images on Instagram.” Visual Communication 0, no. 0 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357219857118.

In summarizing sub-sections 1.3 and 1.4, we can say that the examples we have chosen are not the only widely used and mediatized representations by traditional and new media or political actors. However, they clearly illustrate the ambivalence in the representation of refugees as media figures.

On the one hand, they can be portrayed as victims in need of empathy and protection, on the other hand, the migrants are depicted as threatening others, provoking fear and hostility (Chouliaraki and Stolic 2017). These representations often oscillate between the stereotypical extremes of the ‘speechless victim and evil-doing terrorist’(Chouliaraki and Stolic 2017).

Crucially, they are constructed by others – those in positions of power and authority – rather than by refugees themselves. As a result, they frequently fail to capture the complexity of refugee experiences and displacement trajectories, depriving those affected of their agency. Instead, others speak on their behalf, shaping narratives that may not align with the lived realities of refugeehood and displacement.

1.6 Review

Exercise 2.5

Before we move on to the next section of this unit, here are a few questions to check your understanding of what we’ve covered so far. Look back over section 1 of this unit and answer the following questions:

- Why is the ‘visual turn’ significant in migration studies?

- How has it changed the way migration is analyzed?

- In what ways do media representations shape public attitudes toward refugees and migrants?

- How do visual tropes reinforce the portrayal of migrants as either victims or threats?

- What are the implications of these portrayals?

- What does the term ‘ambivalence in migrant representation’ mean?

- How is it manifested in media and political discourse?

You have now completed Section 1 of Unit 2. Up next is Section 2: What are the key concepts in the (self)-representation of refugeehood?

- Source: UNHCR Mid-Year Trends 2024, 9 October 2024. ↵

- Source: UNHCR Ukraine Emergency site ↵

- Gunter, Joe. “Alan Kurdi: Why one picture cut through” BBC News, September 4, 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34150419. ↵

- Henley, John, Harriet Grant, Jessica Elgot, Karen McVeigh and Lisa O'Carroll. “Britons Rally to Help People Fleeing War and Terror in Middle East.” The Guardian, September 3, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/sep/03/britons-rally-to-help-people-fleeing-war-and-terror-in-middle-east. ↵

- Hussein,Muhammad. "Remembering Aylan Kurdi." Middle East Monitor, September 2, 2020. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200902-remembering-aylan-kurdi/. ↵