Unit 1: Ethical and Methodological Challenges

Section 2: Quantitative studies of displacement at times of war

Research in migration has traditionally tended towards quantitative methods of gathering information.

Quantitative datasets allow for the exploration of important trends and define causal relations between the phenomena in focus.

Yet standard survey methods are unlikely to be effective when planning such studies during acute displacement or in occupied territories.

Surveying displaced people poses numerous methodological, logistical and ethical challenges. Below, we review the main challenges associated with the use of quantitative methods to study war-affected societies in general and particularly displaced populations.

2.1 What are the safety and ethical considerations?

Scholars conducting research in war-affected societies or among displaced populations are, as a rule, required to address safety and ethical considerations with their institution’s Ethical Boards before beginning fieldwork.

In response to the growing number of studies on war-affected societies and vulnerable groups such as refugees, Ethical Boards across the globe have implemented stricter procedures to prevent ad hoc projects lacking thorough methodological preparation, reflection, or trauma-related training.

This often increases the paperwork burden and potentially delays fieldwork during critical moments (e.g., the early days or months after the arrival of IDPs/refugees).

It also helps less experienced researchers anticipate critical issues and prepare more efficiently for challenging situations.

2.2 What are the main challenges to quantitative studies?

Typically, conflicts cause intensive population movements in search of protection, safety, and humanitarian aid. People are forced to move, find themselves on opposite sides of new lines of demarcation or abroad.

Example

In Ukraine, after 2014, part of the population in the occupied territories fled to other regions to escape political and physical persecution and military actions.

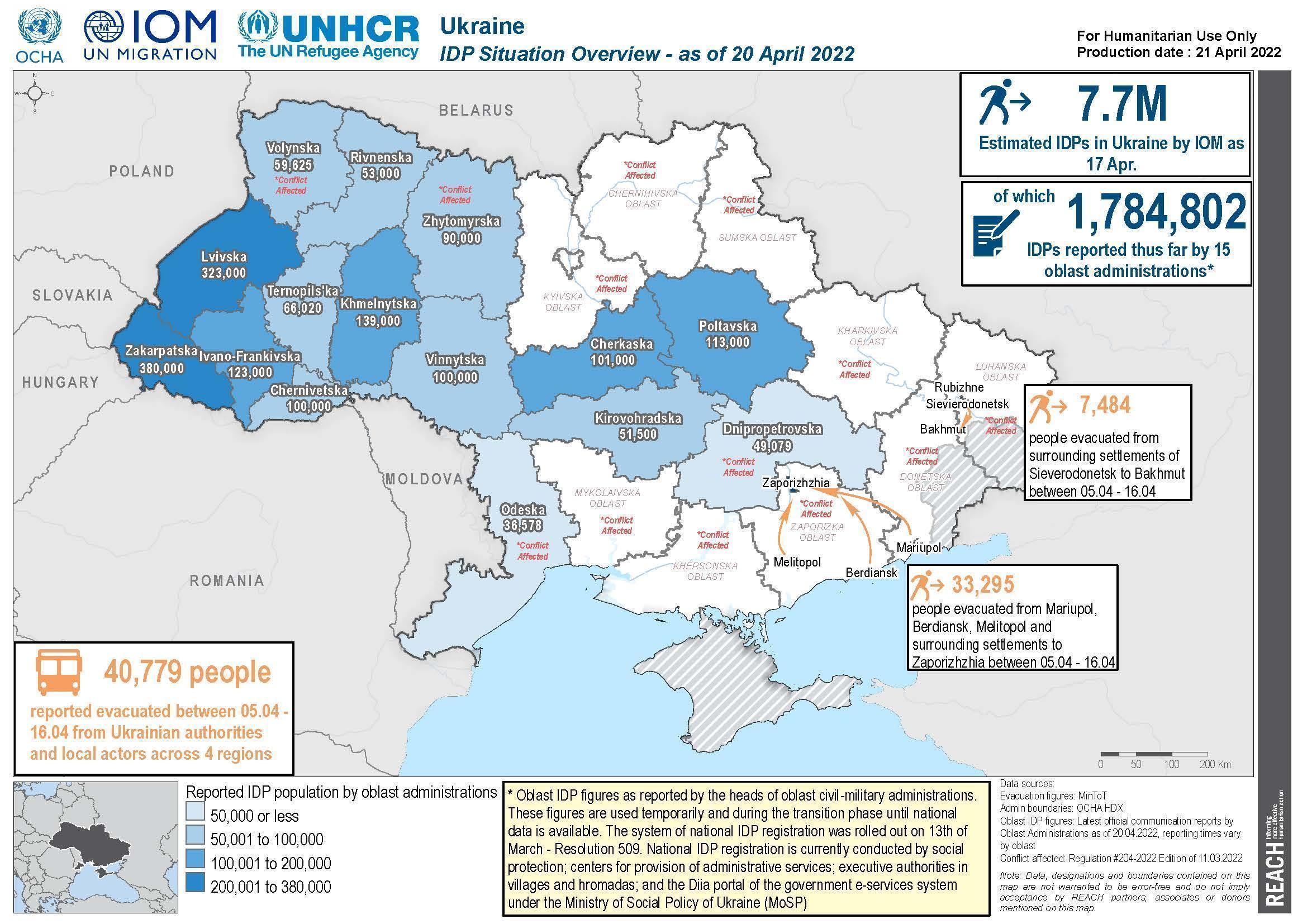

In February 2022, Russia’s aggression provoked the largest European population displacement since the Second World War.

During the first month of the Russian invasion in Ukraine the number of displaced Ukranians reached 12 million people (including 7.7 million IDPs (IOM 2022) and 4.1 million cross-border refugees (UNHCR 2022).

In such situations reliable statistics were not available as to who stayed, who moved, and where they went.

A further challenge brought by military aggression is the time dimension (Howlett & Lazarenko 2023). Under such extreme circumstances, society is extremely fluid in terms of respondents’ localization, opinions, and needs.

This often means that any data obtained will almost immediately be outdated. This places additional pressure on researchers and policymakers to accelerate knowledge production.

This may influence the ability of researchers to follow standard research protocols and have negative consequences on an assessment of its reliability.

2.3 What are the challenges of estimating the target population and sampling?

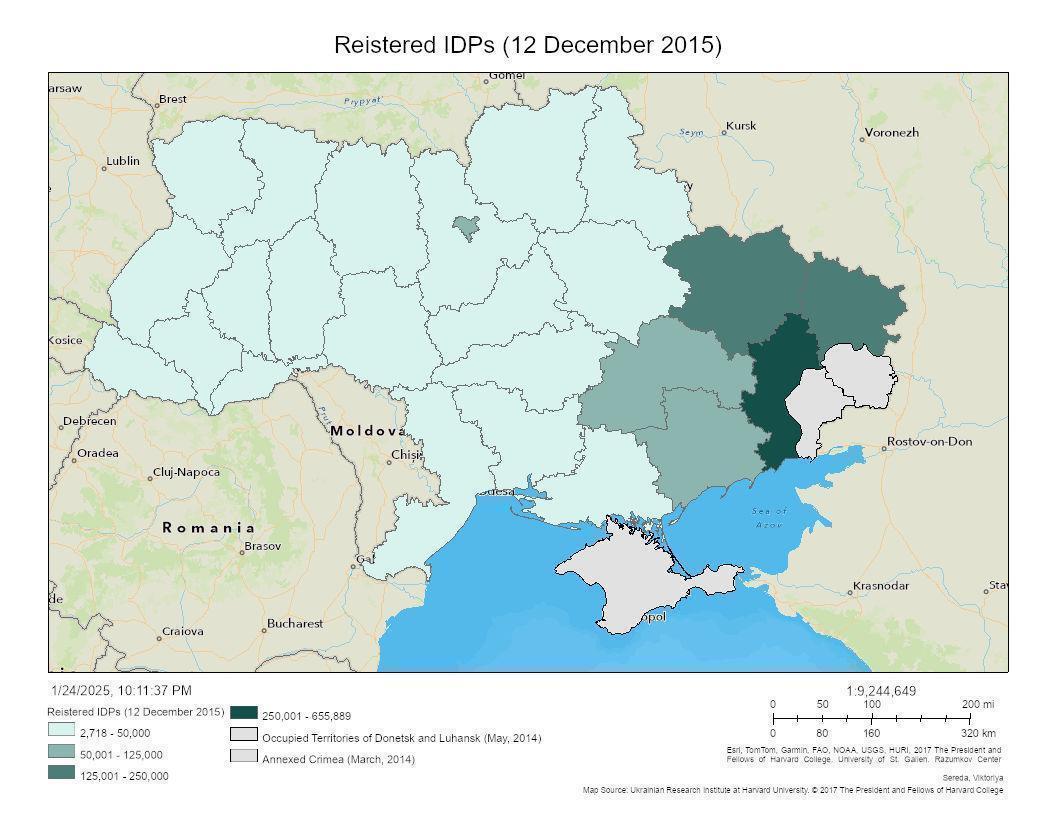

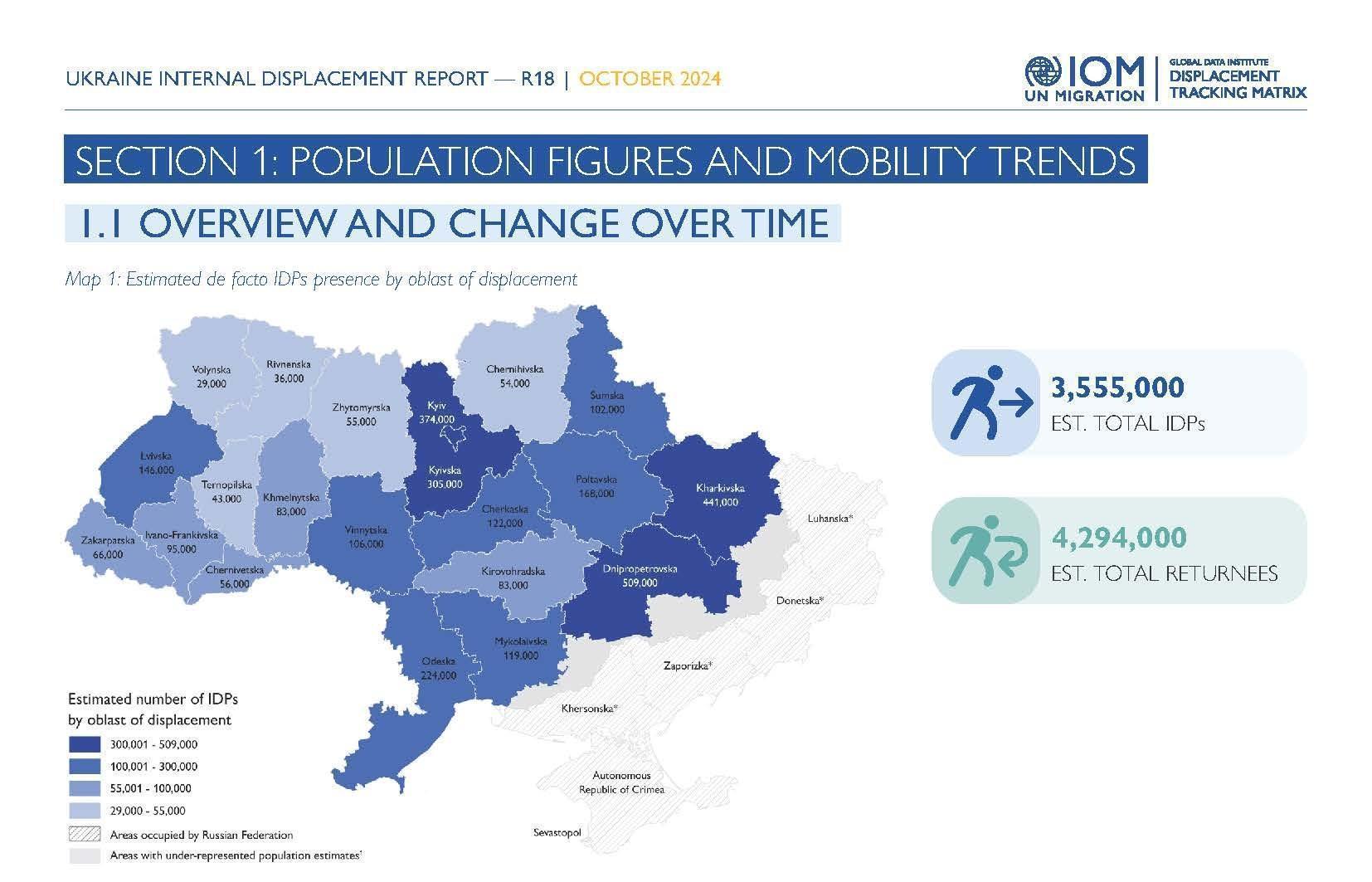

Subsequent estimates and the maps derived from them are often based solely on individuals who officially register (Map 1 and Map 2).

Research on the internally displaced population in Ukraine indicates that up to one-third did not officially register as IDPs, rendering them ‘invisible’ in official statistics (Mikheieva & Sereda, 2015).

Similar patterns are observed in studies of those displaced abroad.

Since 2014, and especially after February 2022, the number of displaced people or those who find themselves under occupation has constantly changed depending on the battlefield situation. As a result, any statistical data and their visualization in, for example, maps easily and quickly become out of date.

It is impossible to define the general population and, as a result, to specify a sample and sample error because of:

- unregistered displaced persons in Ukraine or other countries;

- intensive movement and multiple relocations of a high share of the population (multiple internal displacements; people fluidly shifting between the status of IDP and refugee; refugees moving between different receiving countries; those who choose to return or immigrate again);

- the manipulative nature of data on forced displacement to the Russian Federation;

- limited access to data in temporarily occupied territories.

2.4 Is it possible to carry out a general population survey?

In the case of an undefined general population, a random or systematic sample would be the best solution.

This, however, has its own challenges. Studying temporarily occupied territories would be virtually impossible given the risk to researchers. Military actions and occupational regimes create conditions of fear and danger for respondents and interviewers and critically limit access to a large proportion of the population.

Example

One approach taken by Ukrainian sociologists in 2022 under these circumstances was to construct a sample based on pre-war settlement statistics and subsequently ask respondents:

- Where did they live before the onset of the full-scale war?

- Have they moved since then and, if so, where do they live now?

- Whether the respondent is currently living on territory occupied in 2022?

These responses would be used to weight the sample (Volosevych 2024).

In the case of IDPs staying in Ukraine or refugees fleeing the country, other limitations apply, especially in the early stages of displacement. The official statistics on the target group are first non-existent and then gradually build up. Often this happens with a significant time lag.

One also needs to account for any politicization of categorization and migration data which may also significantly distort available statistics.

You will find more on this in the unit Possibilities, Limitations and Politicisation of Migration Data.

Example

In 2022, Ukrainians in some parts of Germany waited 6-8 months to finally get their residency status.

There were Ukrainians who first stayed 90 days abroad under the visa-free regime and only then registered as forced migrants.

Up-to-date statistics with regard to place of residence, percentage to the rest of the population, age, gender, ethnic composition, level of education might not be available due to data protection or available only on a very aggregated level, without specification at local community level.

It becomes even more difficult to study ethnic, religious or language minorities among the internally or externally displaced. Researchers face challenges of missing data due to the specifics of data collection and protection in different countries (Sereda & Homanyuk, 2024).

The inaccessibility of certain areas and groups of people in war conditions means that statistical data can be difficult to verify, is distorted or restricted, as is the case with the situation of displaced Ukrainians or ethnic minorities in the Russia occupied territories of Ukraine (Kuzemska 2023).

Statistics are also subject to rapid change because data represent people on the move.

All of this greatly complicates sample design and makes many surveys conditionally representative.

A general population survey would also be ineffective, as IDPs and refugees in their new communities make up a small portion of the total population. Many refugees and IDPs live in unstable and often precarious conditions making them inaccessible to general population surveys.

2.5 Do telephone and computer-assisted interviews offer a possible solution?

Another possible technique is offered by telephone interviews based on random sampling.

This type of interview is safer for interviewers. It does not require travel to war-affected territories and allows the capture of respondents on the move.

However, it still endangers the interviewees in occupied territories. Phone calls can be hacked, and voices recorded and matched with sim-card data.

It is difficult to build deeper and more trusting relationships through impersonal telephone calls. It is therefore difficult to expect respondents to be willing to openly express their opinions.

While telephone interviews with IDPs and refugees do not pose immediate physical safety risks, they may still face threats. Family members may remain in occupied territories, or respondents may need to visit these areas in the future for various reasons.

Telephone interviews also significantly limit researchers’ ability to navigate sensitive topics or traumatic experiences of participants without risking re-traumatization.

The proportion of individuals with SIM cards capable of receiving calls from outside temporarily occupied territories—and, in many cases, those who have fled to other countries—is steadily declining.

In occupied territories people might be forced to use local mobile providers, and displaced persons might change providers due to economic or convenience reasons. This further reduces the pool of people who can be contacted and interviewed.

One should also account for possible extensive blackouts due to military activities and destruction of the infrastructure that might create additional barriers for telephone or CATI surveys.

2.6 How representative can samples be?

A general population survey would also be ineffective, as IDPs and refugees in their new communities make up a small portion of the total population. Many refugees and IDPs live in unstable and often precarious conditions making them inaccessible to general population surveys.

When almost one-third of the population is on the move, either as internally displaced persons or as refugees in multiple countries with different political and migration regimes and registrations, it is difficult to have any informed judgement about the representativeness of the sample.

In such acute circumstances scholars also apply other methodologies. Online services, phone applications, and social media platforms are used to collect quantitative data, which often exclude many categories of the population, including those who:

- are untrained;

- reluctant to use these services;

- have no access to the Internet, phones, or computers for economic reasons;

- are prevented by infrastructure reasons such as power outages;

- experiencing regular air raids and missile attacks;

- are displaced;

- are carrying out military service.

The case for using such methods lies in their ability to gather information about a population’s needs and public opinion trends. It is crucial for researchers to openly acknowledge limitations and possible biases of their research.

When triangulated with other similar studies, they can provide insights into settlement patterns and the socio-demographic characteristics of displaced populations. In future these would allow us to build more reliable sampling strategy techniques suitable for small and unevenly dispersed groups.

A typical approach involves incorporating elements of purposeful selection, such as focusing on locations with a higher concentration of resettled individuals or targeting specific groups, like Crimean Tatars, and combining with principles of stratification and randomization. The difficulty is that there might not be localities with a high concentration of target groups.

The gradual transition from the Fordist model of humanitarian aid, characterized by large refugee camps or concentrated settlements, to a model where local civil society and individual actors provide most of the early-stage humanitarian support and housing has made IDPs and refugees even more ‘invisible’ to researchers (especially if they stay with friends or relatives and avoid registration).

Despite the rapidness and the scale of forced migration caused by the Russo-Ukrainian war, the response of receiving societies in most countries prevented the creation of large IDP/refugee camps or concentrated settlements. As a result, the ability to reach the target group may be limited.

This may necessitate the use of alternative sampling methods with limited possibilities of randomization, such as snowball quota sampling. This would involve visiting locations where potential respondents congregate (e.g., religious centers, cultural events) or are required to visit (e.g., government registration points, job centers, language courses).

All this makes it vital that we describe in detail the group under study and the limitations of the study. This will lead to greater caution in our conclusions and interpretations. It will also give the professional reader the necessary information about who and what has been left out of the research.

2.7 What is the role of face-to-face surveys using quota or snowball techniques?

How we conduct face-to-face surveys in occupied territories raises even more questions.

We first need to carry them out through trust networks, following quota or snowball techniques with anonymized questionnaires.

However, this technique might lead to unpredictable bias in the sample. In both methods, respondents might be afraid that they have been contacted not by researchers but by military or secret services to check their loyalty. This might influence their openness, especially regarding sensitive questions.

Scholars involved in field work must know:

- how to conduct research with displaced persons in occupied territories or war zones;

- how to protect data (including digital encryption and protection);

- how to interview people where the ‘spiral of silence’ is at work due to fear and uncertainty.

This does not mean that quantitative studies are not possible in a war zone, but by employing them, one must understand all the limitations, namely:

- with sampling,

- response rate,

- the dangers of fieldwork,

- the limits to which issues can be discussed without putting respondents in a life-threatening situation or causing re-traumatization.

All these issues, usually discussed in academic publications so readers can assess the limitations of the presented data, are often missing in policy reports.

It is important to understand the ethical and methodological challenges that are often present in quantitative research designs and adapt instruments to the given environment. This highlights the need for transparent descriptions of all ethical and methodological challenges that scholars face in obtaining knowledge in conditions of war and displacement.

2.8 Review

We have now come to the end of the second section in the unit. Look over Section 2 and do the following exercises.

Exercise 1.5

Now look over Section 2 and answer the following questions to check you have understood the key points:

- How can researchers balance the need for accurate and reliable data collection in conflict-affected areas with the ethical responsibility to ensure the safety and well-being of respondents and fieldworkers?

- In what ways might the fluidity and unpredictability of displaced populations impact the validity of survey results?

- How can researchers account for these challenges when designing their studies?

- What are the potential biases introduced by different sampling methods, such as snowball sampling or telephone interviews, when studying displaced populations?

- How can these biases impact the conclusions drawn from the research?

- Considering the sensitive nature of conducting surveys with displaced persons and individuals in conflict zones, what ethical considerations should researchers prioritize?

- How can they ensure the safety and well-being of their respondents while still gathering meaningful data?

- What challenges arise when presenting research outcomes on displacement and conflict-affected populations in the media?

- How can researchers ensure that their findings are accurately represented while addressing the nuances and limitations of their studies?

Exercise 1.6

Look at John O’Loughlin’s (University of Colorado) and Gerard Toal’s (Virginia Tech) lecture “The Perils and Benefits of Surveying in a Conflict Zone: Cautionary Tales and Results from Donbas 2020-2022.”

You will need to read the following summary of the lecture:

The lecture explores the challenges and complexities of conducting surveys in occupied territories and de facto states. It focuses on comparing data from previous surveys in Donbas, collected by the speakers, with surveys conducted by ZOIS in 2016, 2019 and 2020. A significant portion of the discussion is dedicated to their joint study from January 2022, which surveyed both occupied and non-occupied parts of Donbas.

This study aimed to investigate how survey design influences responses. The experimental design involved two separate sub-samples, with data collected on occupied territories by different polling companies—one Ukrainian (KIIS) and one Russian (Levada-Center). The results were compared to assess the impact of the polling company on the responses. While differences were minimal for some questions, they were pronounced for sensitive topics. The lecture concludes with a discussion of the study’s limitations.

Step 1

After reviewing the material, identify the key challenges and limitations associated with conducting research about the people living under occupation, especially through phone surveys. Think about whether any additional issues should be considered.

Step 2

Open “What Political Status Did the Donbas Want? Survey Evidence on the Eve of Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.”

In this research, CATI surveys were conducted for both governmental-controlled and non-governmentally controlled territories of Donbas. For government-controlled territory, two survey companies were used: KIIS based in Kyiv and R-Research based in Western Europe. For occupied territory two survey companies were used as well: KIIS and Levada based in Moscow.

Open page 10 with the results of the survey.

Step 3

Look at the results for such questions as “Not enough for food”, “Enough for food – not for clothes or shoes”, “Enough for clothes -defer other purchases”. “Can buy expensive items (TV, refrigerator etc)”, “Can buy anything we want” for both government-controlled and non-government-controlled territories of Donbas.

- Are there notable differences in respondents’ answers based on their location or the survey company conducting the research?

- How sensitive would you consider these questions? Reflect on your findings.

Step 4

Examine the results for such questions as “Preferred status in Ukraine (with or without autonomy)”, “Preferred status in Russia (with or without autonomy)”, “Self-identified Ukrainian (citizen or by descent)”, “Self-identified Russian (citizen or by descent)” for government-controlled territory by KIIS (based in Kyiv) and R-Research (based in Western Europe).

- Are there notable differences in the answers based on the location of the survey company conducting the research?

- Would you consider such questions sensitive? Reflect on your findings.

Step 5

Now, examine the results for the same questions for non-government-controlled territory by KIIS (based in Kyiv) and Levada (based in Moscow).

- Are there notable differences in the answers based on the location of the survey company conducting the research?

- Would you consider such questions especially sensitive in the context of the occupation?

- If so, how do you think the location of the survey company might affect the answers to such questions in the contested areas?

- Potentially, what other questions could cause such differences in the results? Reflect on your findings.

Step 6

Reflect on the potential problems and limitations of the phone surveys and, overall, quantitative research that generalizes the population in the contested areas after previous steps.

How should a researcher approach presenting such results?

Exercise 1.7

Look at the following document:

Active Group | Marketynhovi Ta Sotsiolohichni Doslidzhennia. 2024. “Nastroi Zhyteliv Tymchasovo Okupovanykh Terytorii Ukrainy/Sentiments of the Residents Living in the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine | Active Group,” May 24, 2024.

Read the following summary before attempting the exercise:

In the first half of 2024, the Ukrainian sociological and marketing company Active Group carried out the first wave of a series of studies focused on analyzing the sentiments of residents in occupied territories. The research was conducted through in-depth interviews using snowball method with respondents from five occupied regions: the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhya oblasts.

The interviews were carried out using such messengers as WhatsApp, Telegram and Signal (Note: as of February 2025, Signal and WhatsApp are unavailable in occupied territories of Ukraine without VPN) for the safety of respondents. The study for each oblast also includes a brief media monitoring of the residents’ activity in the local Telegram chats and VK groups. Overall, this research provides a rare glimpse into the life of the residents living under occupied territories, the topic that got even more challenging to study after the start of the full-scale invasion.

Step 1

After assessing the material, determine the main challenges related to conducting research under occupation.

- How do you think these challenges have shifted since the full-scale invasion began?

- What new challenges can you identify?

Step 2

Open the study on the occupied territory of the Donetsk region. Read the summary (p. 4-6). Determine the main themes discussed in the study.

- How sensitive do you find them? How truthful do you think the respondents’ answers could be?

- Discuss possible limitations of conducting face-to-face interviews through messengers in the context of the occupation.

- Do you think that, currently, there is a viable way to do quantitative research on people’s political affiliations under occupation? Reflect on your findings.

Step 3

Review the media monitoring of local Telegram chats and VK groups (p. 2-3). Identify the key findings.

- How sensitive do you consider these findings?

- Could they have been uncovered in face-to-face interviews?

- Discuss the potential advantages and limitations of studying residents in occupied territories through social media. Reflect on your findings.

Exercise 1.8

Open “MAPA. Digital Atlas of Ukraine”, section Contemporary Atlas of Ukraine “Donbas and Crimea in Focus” Module. Open “View the Donbas and Crimea Web Map”.

(View a tutorial on how to work with the MAPA project)

Step 1

Open section “Colour-Coded Maps” and sub-section “Donbas war and Annexation of Crimea” and activate maps “Attitudes to IDPs from Donbas 2017” and later “Attitudes to IDPs from Crimea 2017”.

Compare the two maps.

- Are there visible regional patterns?

- Do all the oblasts’ dwellers have the same positive (or negative) attitudes to both groups of displaced?

- Explain your findings.

Step 2

Open section “Colour-Coded Maps” and sub-section “Donbas war and Annexation of Crimea” and activate map “Registered IDPs 2015-2019”. Now you have two layers combined.

Layer 1 (colour-coded base) “Attitudes to IDPs from Donbas 2017”

Layer 2 “Registered IDPs 2015-2019”.

- Could we say that oblasts with the most positive attitudes towards IDPs correspond with oblasts where we observe the highest number of registered IDPs?

- Comment on your finding.

You have now completed Section 2 of Unit 1. Up next is Section 3: Qualitative studies of war and displacement.