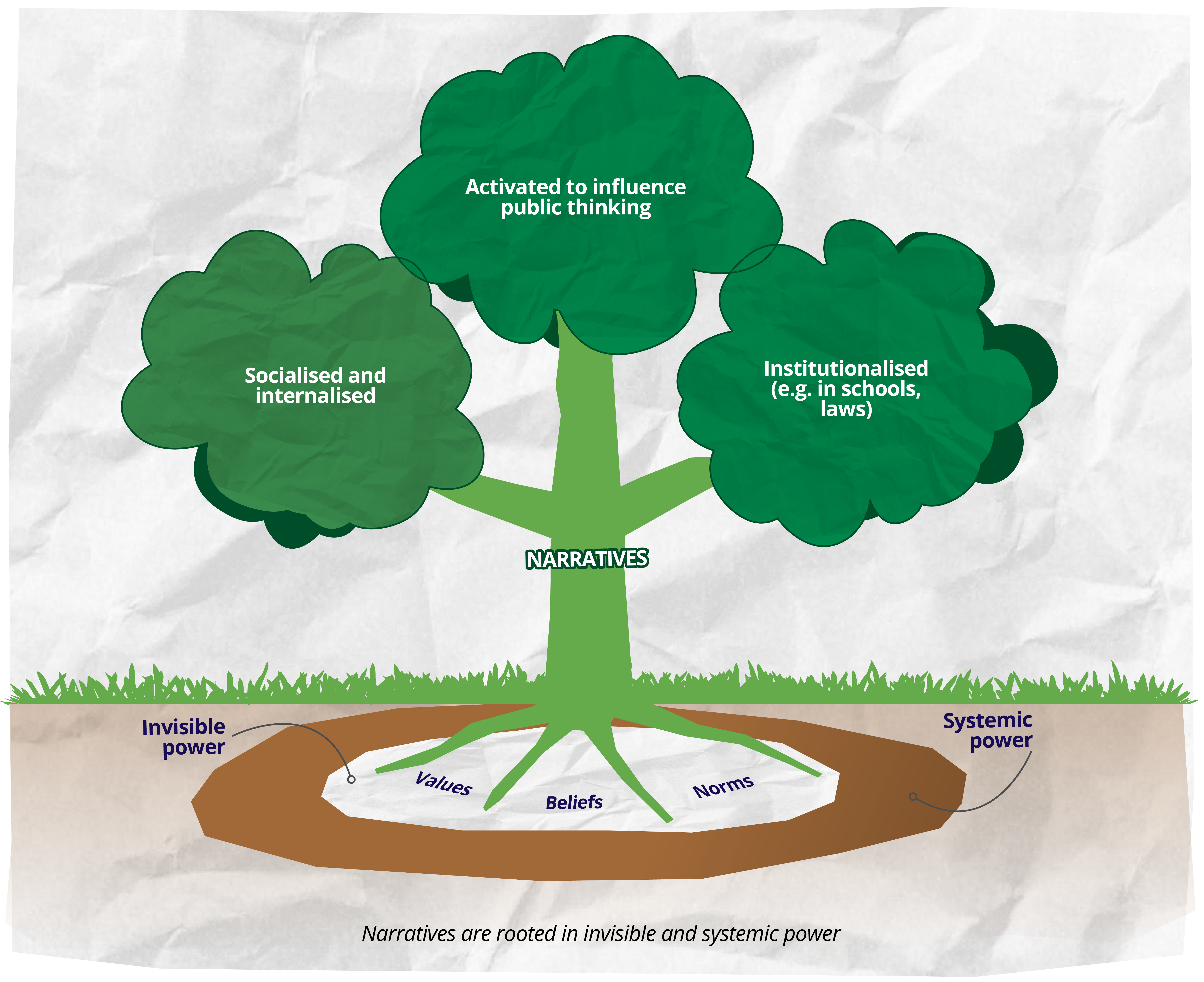

Theme 3: Invisible and Systemic Power in Narratives

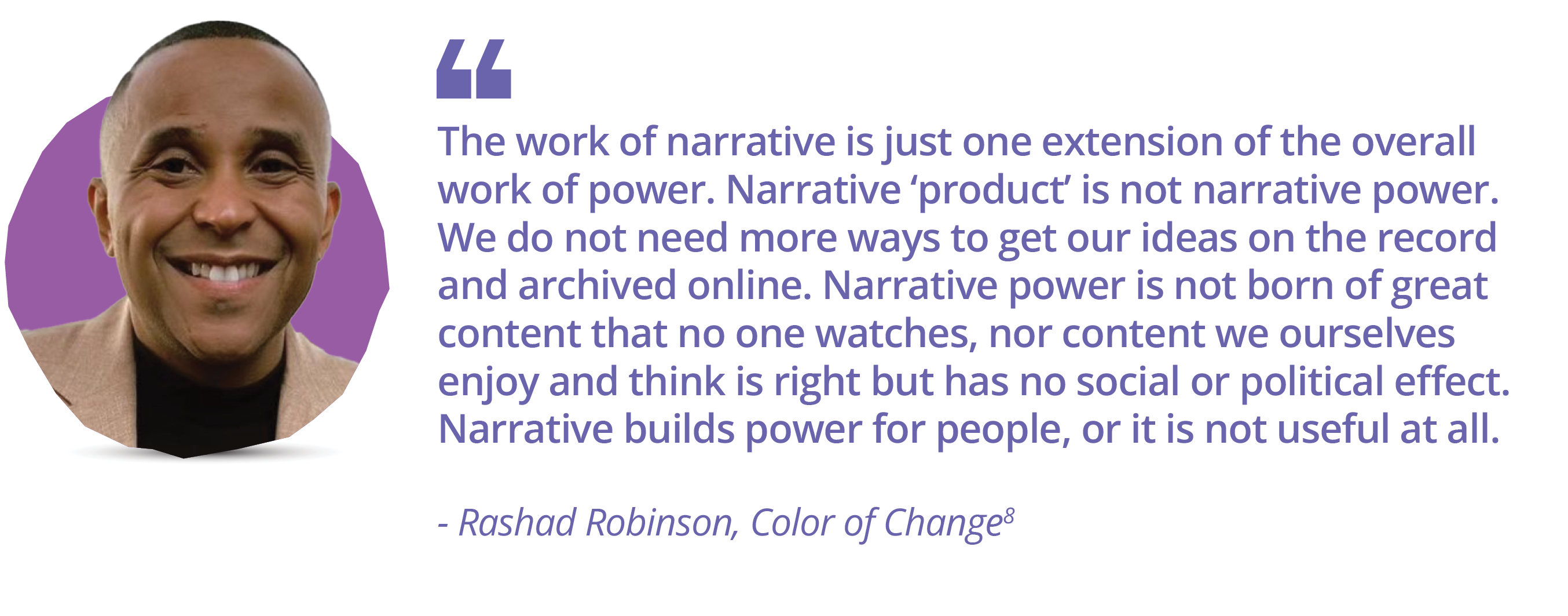

Narratives build directly on invisible and systemic power. They align with socialised norms and beliefs and with the underlying systemic logic of societal institutions and structures. For this reason, a key social change strategy is to ‘unmask’ oppressive and polarising narratives and contrast them with a different way of seeing things. This enables us to develop critical awareness, common ground, and justice-oriented political choices.

To be effective in challenging a negative narrative, we must do more than contradict it. We must dig into the beliefs and ideas about inclusion, empathy, and fairness that exist in all societies and bring these to the forefront.

Invisible and systemic power in narratives

Operating across three, related dimensions, invisible power is …

- Socialised. Values, norms, and beliefs are reproduced through everyday socialisation, often unconsciously, by all actors ( for example, those of patriarchy). Here, invisible power is the collective internalisation and embodiment of values about ourselves and others and what is good, right, or normal.

- Institutionalised.These same values, norms, and beliefs are reflected and embedded in the logics and hierarchies of many social structures and institutions – from families and education to laws and economics. Building on and reinforcing socialisation, here invisible power is the pervasive reproduction of deep structures in society.

- Mobilised. Dominant narratives are used consciously and intentionally to shape and manipulate beliefs, reinforce social hierarchies and inequalities, and uphold the power, legitimacy, and privilege of some groups over others. They seek to explain what’s wrong and what needs to be solved and who and what’s to blame. Here, invisible power is wilfully exercised at the service of political interests and often accompanied by a legal and policy agenda. Although narratives operate in this dimension, they are grounded in the other two.

In all three dimensions, these norms and beliefs are underpinned and reinforced by systemic power – the logic and codes that define all relationships, such as patriarchy, structural racism, extractive capitalism, and colonialism/imperialism. Like invisible power, systemic power is a contested arena in which alternative logics and codes – expressed in contrasting narratives – compete with the dominant ones. For example, identity can be both a cause of oppression and a source of connection, community, and liberation. Because invisible and systemic power are socialised, institutionalised, and mobilised, many strategic entry points exist for activists and movements:

- Affirming positive norms and beliefs.

- Reforming and rebuilding institutions.

- Creating and mobilising transformational narratives.

Download handout: Invisible and systemic power in narratives.

Activity 3: Power and narratives

Explore how narratives are part of invisible and systemic power, shaping and reinforcing norms, beliefs, and ideologies through socialisation, cultural traditions, and behaviour – and through the systemic power of patriarchy, structural racism, extractive capitalism, and colonialism. In narratives, invisible and systemic power meet visible and hidden power. Powerful actors can leverage the power of beliefs and prejudices to achieve their ends. (This activity and approach to narrative analysis and change is inspired by the work of David Mann and the Grassroots Power Project, USA.)

In this activity, groups apply a framework to delve into the various layers that make up a narrative (stories, messages and explanations, communication, values and behaviour, and who benefits).

Materials: Flipchart paper, markers, handout: Invisible and systemic power in narratives

Step 1: How are narratives related to invisible and systemic power?

Plenary: Refer to, repeat, or do two activities:

- Arenas of Power framework in Chapter 3: Making Sense of Power

- The Master’s House activity in Chapter 4: Identity, Intersectionality, and Power

Review the concept and meaning of invisible and systemic power. Ask participants what they remember from The Master’s House activity.

We can track invisible and systemic power working through different narrative strategies.

- Narratives that divide – causing fragmentation among allies, weakening movement unity, exploiting existing faultlines and prejudices

- Narratives that de-legitimise, stigmatise and criminalise activists and movements – undermining community leadership, fomenting distrust

- Narratives that distract – focusing attention elsewhere, away from actual issues

- Narratives that promote despair – reiterating powerlessness and oppression.

- Narratives that drive danger – creating fear, criminalising people, justifying violence

Individually: Looking at the handout Invisible and systemic power in narratives, each person reflects on their own experience of these different kinds of power.

Plenary: People share reflections on the impact of dominant narratives. Discuss how these narratives reinforce one another.

Step 2: Applying the framework

Plenary: Referring to the handout: Invisible and systemic power in narratives, discuss how invisible and systemic power are socialised, institutionalised, and mobilised or activated. Ask:

- How are the stories, messages, and explanations in dominant narratives mobilised to serve the interests of particular groups?

- How are these narratives institutionalised in the family, law, education system, religions, economic and political structures, and social systems?

- How do these narratives build on – and reinforce – deeper layers of socialised values, beliefs, norms, and habits? How are they related to the systemic logic behind relationships?

- What is the impact of narratives on people’s lives? How do these narratives serve the political and economic interests of those who promote them?

Step 3: How do invisible and systemic power underpin a narrative?

Explore one example together, using the questions below, before applying the framework in plenary or small groups. One example is the narratives about LGBTQI+ people. You could choose another example.

Plenary: To understand how invisible and systemic power underpin a narrative, focus on the example of LGBTQI+ people. Unpack the stories, messages, and explanations in the dominant narrative, and then examine how this is enabled by – and reinforces – invisible and systemic power. Discuss personal experiences of this narrative.

What are the main messages, stories, and explanations in the dominant narrative? Think about the difference between the messages you hear and the stories behind them. For example:

- Messages: “LGBTQI+ people put our kids at risk.”

- Stories: “LGBTQI+ people are immoral and outsiders, not part of our families, and prey on our children.”

- Underlying beliefs: “Non-heterosexual relationships are evil, sinful, and unnatural.”

How are these messages communicated, and by whom? For example:

- In conservative religious communities (sermons, literature, school lessons, informally), by religious leaders, educators, community members

- In political messages, speeches, and campaign materials, by politicians, party officials and activists, conservative media outlets, party supporters.

- In social media, everyday language, parents with their children.

- In symbols, images, cultural activities, social and body cues.

What actions or impact do these messages produce? Whose interests do they advance? For example:

- Everyday exclusion, prejudice, and discrimination against LGBTQI+ people.

- Violence, hostility, and harassment.

- and policies that discriminate against LGBTQI+ people, such as marriage rights.

- Conservative and traditional explanations of an unequal social order and strict gender roles with males as dominant fathers and women as mothers and carers.

- Patriarchal control of sexuality for the purpose of reproduction only.

- Domestic violence as a private matter.

What is the dominant narrative created by the above? For example:

- LGBTQI+ people are outsiders, immoral, not normal human beings, not part of our families and communities; they don’t belong in society and pose a threat to our children.

What kinds of institutions and structures in society give strength to – or are strengthened by – this narrative? For example:

- The ‘traditional family’ is the centre of society; marriage is for the purpose of raising children; sex is for reproduction, not pleasure; any sexual or gender expression or identity that does not conform to these values is a threat to society.

What kinds of socialised values, norms, and beliefs are behind this narrative? For example:

- Beliefs and ideologies: conservative religious beliefs, traditions and teachings about sex and sexuality, families, gender, women’s roles, and marriage.

- Social norms: patriarchal views about marriage between a man and a woman only (heteronormative) emphasising that there are only two genders – male and female – with their ‘proper’ roles in society – masculine and feminine – (binary-gendered as ‘normal’).

- Embodied habits: gendered behavioural norms of masculinity, femininity, sexuality; how we reproduce these norms in our everyday speech, behaviour, and actions.

Plenary or small groups: Explore another dominant narrative of interest to the group, using the same questions and drawing on the example above. Alternatively, small groups work on different narratives. If working in small groups, share highlights in plenary.

Step 4: Transforming narratives and invisible power

Plenary: So how can we break this cycle and transform the dominant narratives?

Invite a quick brainstorm of ideas, without going into depth on specific strategies. List ideas on cards or flipcharts, and cluster into categories if helpful. Raise or emphasise the following key points in the discussion:

- A starting point for shifting a dominant narrative – and the invisible and systemic power behind it – is to identify and express our own positive narratives and visions of society.

- We call these positive narratives ‘contrasting’ or ‘transformational’. If we use the terms ‘alternative’ or ‘counter-narratives’, we are still centring the dominant narratives which give them power. Positive narratives have always been there.

- We reveal and elevate positive narratives that are already there – grounded in long-standing progressive values and beliefs – rather than talk about ‘creating’ new ones.

- Exploring the emotional resonance of narratives is a good starting point for identifying positive narratives. Notice how the dominant narrative makes you feel. Which of your own values or beliefs do you feel are challenged by this narrative? Which of your values or beliefs contrast with this dominant narrative?

- What are some examples of positive and contrasting narratives and messages? For example:

Narrative: LGBTQI+ people are loved and loving parts of families.

Message: love makes a family, love is love, we all belong.

Narrative: all black, indigenous, and people of colour have as much value and significance as any other human being

Message: Black Lives Matter

Small groups: All work with the same dominant narrative, or each group works on a different one. Each group has ten minutes to reflect on the questions and five minutes to prepare a creative drawing or dramatic presentation. Start by reflecting individually on one of the dominant narratives we explored today with these two questions:

- How does the dominant narrative make you feel?

- Which of your values and beliefs does the narrative contradict?

On pieces of paper or cards, write short, simple statements that express your own values and beliefs on the theme. Write from the heart, and don’t worry about exact words.

Take turns each sharing one or two statements that you feel very strongly about.

Cluster the statements into categories, and choose one cluster to discuss together:

- Which values and beliefs do you hold that lie behind these statements?

- Where do they come from?

- How do you live and express these values and beliefs in daily life?

Prepare a short, creative presentation – a diagram, drawing, symbol, message, dramatic scene, or body sculpture – to show what the dominant narrative looks like and what your own contrasting values, beliefs, and behaviour look like. Be creative and expressive, and feel free to use images, symbols, or metaphors to convey your values, beliefs, and ways of being.

Step 5: Bringing our values to life

Plenary: Ask each group to share their creative representation of the dominant narrative and the values and beliefs of the group. After each presentation, invite a quick round of reactions:

- What did you see or hear? How do you feel?

- What values and beliefs are being expressed?

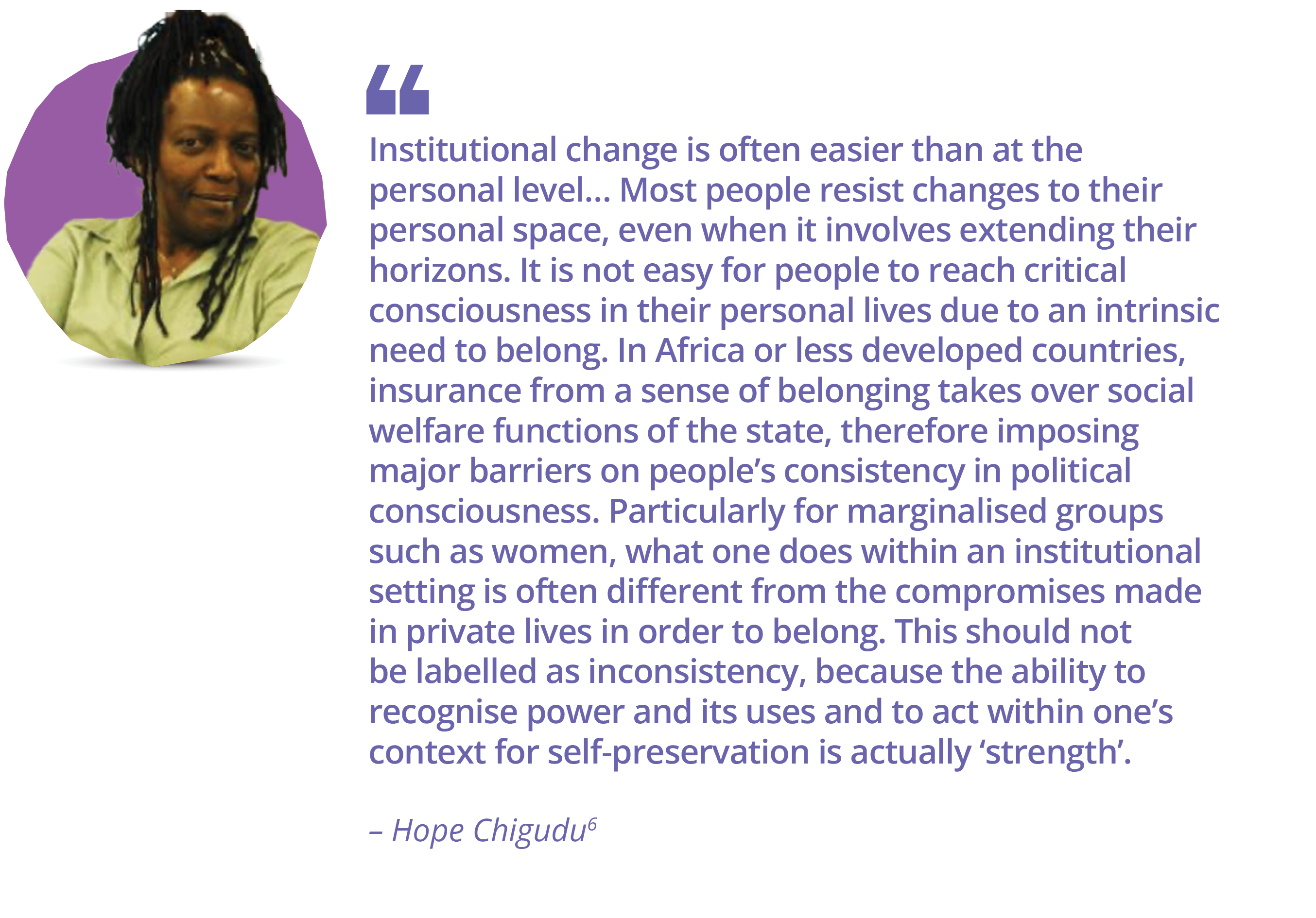

Values, norms, and beliefs are in constant flux and are contested. In every moment, they can be affirmed or resisted, complied with or rejected, through words and behaviour. Invisible power shifts and evolves, sometimes slowly, sometimes quickly, sometimes passively, sometimes due to proactive agency. It can at times be strategic or safer for activists to remain silent and ‘comply’. How and when do we resist or comply with dominant narratives?

Share the handout Resisting dominant narratives. Discuss how we resist or refuse to comply with a dominant narrative. Ask:

- What are some examples of strategic resistance to narratives?

- What values and beliefs give strength to our position?

- Where do these values and beliefs come from?

- Who has upheld them over time? Who or what has inspired us?

- Is there a transformational narrative that flows from these values and beliefs? If so, what is it?

Download this activity.

Resisting dominant narratives

Resisting dominant narratives

We might remain silent or passive in the face of a dominant narrative, perhaps because we have internalised the narrative’s values. But silence can also be strategic: the moment may not be right or the risks too great to speak out or resist. We may choose to express resistance less directly.

Why do we sometimes remain silent or passive when faced with a dominant narrative? Think of specific examples.

- Is compliance automatic or unconscious?

- Do we sometimes consciously comply with a narrative, even if we don’t agree with it?

- When, and why, would we choose to comply with narratives we don’t like? (for example: for safety, for fear of being shamed or excluded by those around us.)

- When might it be strategic to remain silent or comply with a dominant narrative?

- If we notice others complying, is it always okay to ‘call out’ or shame them? Give examples.

Calling out or shaming people publicly for going along with a dominant narrative can be strategic, particularly if powerful people are advancing the narrative. But in everyday life, this can alienate people. We may not understand the reasons for their compliance. Black feminist activist Loretta Ross advocates dialogue with those we disagree with, or calling in, rather than calling out.7

Download handout: Resisting dominant narratives.

_____________________________________________

6 A New Weave of Power, People and Politics, 2002, p. 53.

7 For more information, see Loretta Ross TEDTalk, “Don’t call people out, call them in”.

8 https://nonprofitquarterly.org/changing-our-narrative-about-narrative-the-infrastructure-required-for-building-narrative-power-2/ July 17, 2020