Theme 2: Multiple Forms and Arenas of Power

The frameworks in this section – developed, adapted, and refined over the years – help us make sense of the shifting and conflicting dynamics of power.5

Activity 2: How do you analyse power?

This optional activity is designed for working with organisations and individuals who may have their own frameworks and tools for planning and analysing power. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to understanding power. In this activity, ask participants:

- What tools and approaches do you use to make sense of power?

Explore people’s existing ways of understanding power before introducing the Guide’s frameworks.

Materials: Virtual board with stickies (such as miro) or flipchart paper, markers

Definitions and symbols of power created in Activity 1 (on flip charts or virtual equivalent)

Handout: What and where is power?

Community market or sharing circle

For a community market, people present their tools and approaches on flip charts or handouts at different ‘market stalls’ around the room. The group walks around the ‘marketplace’ from one stall to another. Each stallholder explains briefly what they are ‘offering’.

Alternatively, people form a circle and take turns to present the approach they have used in the past, outlining the purpose, application, strengths, and any challenges the tool may present. Invite comments and discussion.

Plenary: Discuss:

- How do these different approaches help us understand power?

- How do they help us strategise in a way that considers power?

- What’s missing? What questions or challenges do they raise?

Download this activity.

Power is dynamic and can be both negative and positive, depending on how it is used, by whom, and for what purpose.

Although some forms of power are deeply entrenched and violent, all power is contested in some ways. There are always possibilities – even very small – for creating power that is transformative.

When we contrast power over and transformative power, we sometimes imagine two cleanly distinct types of power battling each other, like good and evil. But they co-exist, even in the same groups and organisations.

Creating transformative power is a winding road, not a linear process.

Four arenas of power

This framework proposes four interconnected arenas where power is in dispute, to help us to unpack the different ways in which power operates and thus to identify ways of exposing, challenging, and transforming it. Social movements and allies – imbued with values of equity, dignity, liberation, and love – constitute a fundamental force to upend oppressive and discriminatory power dynamics.

Formal decision-making – including laws, courts, policies, budgets, enforcement, policing, regulations, and institutional rules and procedures at all levels, local to global. This includes elections, appointments, and enforcement, from police and judges to Members of Parliament, bureaucracies, services, and local authorities. Visible power – formal decision-making – also exists in most institutions from churches and mosques to corporations, unions, and NGOs. Depicted as neutral, decision-making and implementation/ enforcement often discriminates by race, gender, class, location, and other factors. Exclusion is perpetuated by unrepresentative, closed, and discriminatory processes and structures. People, organisations and movements work to open decision making, change decisions and who makes decisions, and ensure fair enforcement and accountability.

Organised social, political, and economic interests – both legal and illegal – seek to influence and control formal visible power and shape what is prioritised and decided, and how decisions are enforced. For example, corporations, religious, and political groups operate parallel to or in collusion with state actors (visible power) to define priorities, policies, and budgets to serve their economic interests and political power. We call this ‘hidden power’ because, even though we can sometimes see the interests involved, they work behind the scenes to exercise influence with formal governance structures to control what is decided and whose interests matter. At times, they resort to lawsuits, surveillance, and violence to silence dissent and delegitimise alternatives. People, organisations, and movements expose and challenge these entrenched interests, but also influence visible power across the political spectrum, as do right-wing groups and illegal ‘shadow’ actors such as organised crime.

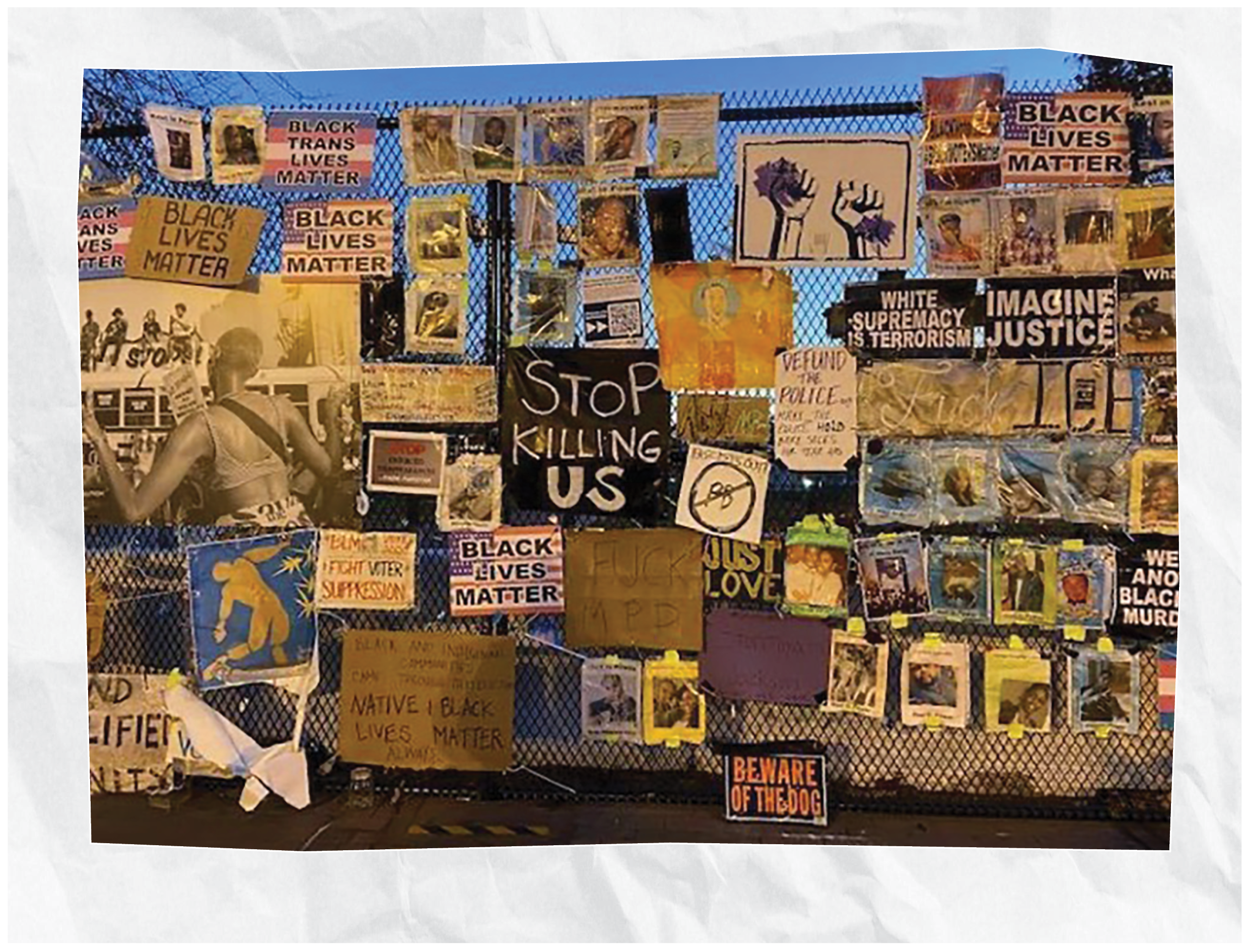

Beliefs, ideology, social norms, and culture that shape people’s sense of what is right, normal, and real. This includes deeply held, often unconscious prejudices based on gender, race, class, sexuality, location, age, and ability. The media, education, religion, and social rituals help to socialise particular beliefs, values, and narratives that legitimise and normalise injustice, discrimination, and violence. Manipulating invisible power through information and distorted narratives can turn people against each other and generate fear and distrust, often without people being aware of it. People, organisations and movements work to challenge and transform social norms and values through awareness raising, political education, narratives, and communications strategies.

Deeply embedded logics work like operating systems to shape and structure all social and economic arrangements. Dominant ones include patriarchy, structural racism and white supremacy, capitalism, and colonialism-imperialism. Together, these logics naturalise a dehumanising dominant–subordinate hierarchy based on violence and the exploitation of each other and nature. These logics are like the genetic codes that determine economic, political and social relationships and permeate institutions, which in turn shape our lives. Marxism, liberation theology, feminisms, decolonialism, and abolitionism are all ideologies that seek to replace these logics with more equitable, sustainable, and inclusive economic and social relationships. People, organisations, and movements who successfully contest power in the other three arenas can also challenge and transform power at the systemic level.

Download handout: Four arenas of power.

Activity 3: Arenas of power

The idea that power operates in different dimensions and arenas is foundational to this Guide and rooted in political theory and insights from years of social movement-building experience. Many people and organisations have used and adapted this framework to analyse how power affects them and develop strategies to transform power.

Step 1: Introduce the framework

Materials: Handout: Four arenas of power

Plenary: Refer to the handout: What and where is power? and reiterate key points.

In pairs: Building on the earlier activities about power and powerlessness, brainstorm as many examples of power from your context and social change experience, being sure to include both negative and positive forms. Identify two examples and write them on cards:

- One example of power as negative (as control, abuse, coercion).

- One example of power as positive (as liberating, creative, transformative).

Plenary: As pairs share their examples, cluster their cards on the floor or wall. Then, as you present the frameworks, draw examples from participants’ cards of:

- Visible power (making and enforcing the rules); hidden power (influencing and setting the agenda); invisible power (shaping norms and beliefs); systemic power (the deeply embedded logics that define social relationships).

- Power over: the oppressive use and abuse of power to exploit, control, dominate, and exclude.

- Transformative power (power within, power with, power to, power for).

Distribute the handout The four arenas of power and facilitate a discussion. Focus on clarifying the frameworks. In conclusion, invite discussion by asking:

- How are these arenas of power useful in helping you work out what and who you’re up against and where to focus your change work?

- How can they be useful in guiding your efforts to build and use your own power to challenge and change injustice?

- What questions do the arenas raise that you might explore and clarify when you apply them to your own work and issues or to case studies?

Step 2: Apply the four arenas of power

This framework helps reveal how power is operating and where there are opportunities to expose, contest, and change power in relation to real contexts and issues.

Choose one of three options as the basis for analysing the four arenas of power:

- the historical timeline created in Chapter 2: Naming the Moment

- a case study (three are provided)

- participants’ own experiences and issues (note: this can be enriched by the learning from one of the options above first)

Materials: Use several large pieces of paper to map out the arenas of power as groups name them. Alternatively, create a simple grid with a row for each of the four arenas of power and two columns. In the first column, groups note how powerful interests in this specific arena of power contribute to the problem. Leave the second column blank for exploring how movements challenge these dynamics of power.

Option 1: Use the timeline created in Chapter 2: Naming the Moment or do the timeline activity now. Post the timeline on the wall. Look at the whole timeline, or form groups by age and experience to focus on a section of the timeline.

Option 2: Choose one of the case studies or provide your own.

UBUNTU: Rural women mobilise in South Africa

PEKKA: A grassroots women’s movement in Indonesia

COPINH: Guardians of the River in Honduras

Read the case study individually or aloud in turns.

Option 3: Handouts or resources related to the group’s issues and agendas. Identify a maximum of three issues that your group is working on or care about.

Small groups: For any of the three options:

- Identify a moment when power was challenged. What were the issues or events at the centre of this moment?

- How and where did power play out in relation to the four arenas of power? Who were some of the dominant actors, and what were their interests?

- How has exclusion or violence been reinforced or legitimised in each arena of power?

- Visible: making and enforcing the rules

- Hidden: influencing and setting the agenda

- Invisible: shaping norms and beliefs

- Systemic: defining the logic of all structures and relationships

- What social justice strategies or ways of organising did the movements or community groups use to enhance and mobilise their influence to disrupt, resist, challenge, or change power in these arenas? Identify up to three strategies.

Plenary: Consider each of the questions above in turn. Invite one of the small groups to share their thoughts, then ask others to add or build. Small groups take turns to share first. Note key words and ‘aha!’ moments on flip chart. For variety, invite groups to present their thoughts in creative ways such as a lively talk show (TV or radio), a three-to-five-minute skit, a story, or a song.

To conclude, ask and discuss:

- Which of the four arenas of power were you able to identify?

- Who and what was in conflict? How did the groups involved try to address injustice or shift power?

- Was the framework useful? What did the arenas of power reveal?

Download this activity.

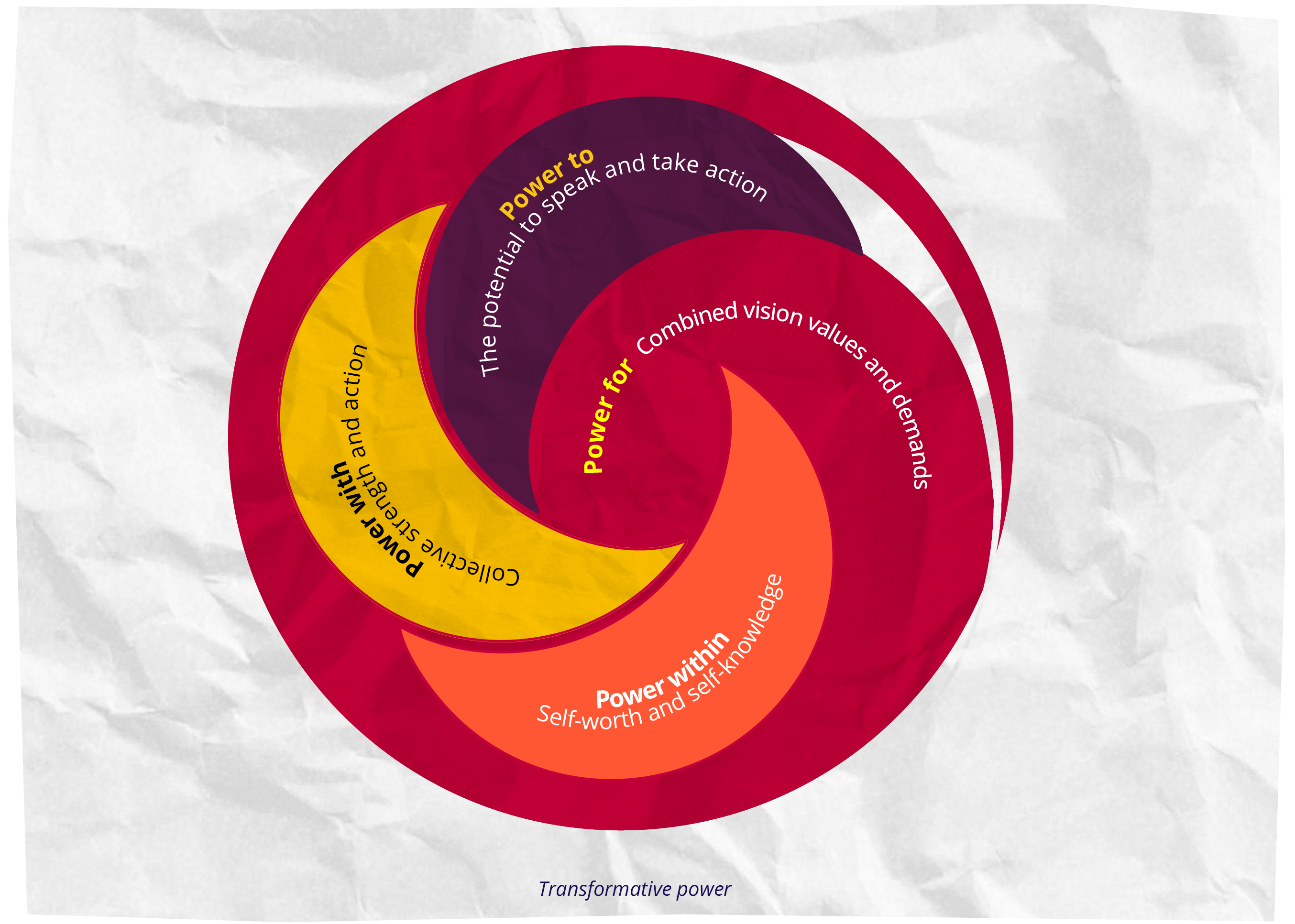

Transformative power

Power is also a positive and regenerative force for change that centres around an alternative ethic of caring and interdependence – personal, social, political, and organisational. It can be experienced as a sense of one’s dignity, empathy, and belonging and an ability to imagine alternatives to the status quo, and expressed in creative and collective work to forge a different path and make change happen.6

- Power within: self-worth and self-knowledge

Grounded in a belief in inherent human dignity, power within means self-esteem and the ability to challenge assumptions, value interdependence, feel empathy, and seek fulfilment. Grassroots organising, leadership development, and joyful connection help people affirm their personal worth, tap into their dreams and hopes, and discover their power to and power with. - Power to: the potential to speak out and take action

Leadership for social justice involves new skills, knowledge, and awareness that taps into the sense of hope and possibility for change. It opens up possibilities for individual and joint action or power with others. Nurturing our power to is a critical antidote to resignation and fear. - Power with: collective strength and action

Finding common ground and community with others to work together for change, power with is expressed in collaboration, alliances, reciprocity, belonging, solidarity – and collective action. It multiplies individual talents, knowledge, reach, and resources, all of which are essential for transformational change. - Power for: combined vision, values, and demands

Orienting our change strategies and practices, power for is the vision, values, and propositions that steer and inspire action and connections and that move us toward the change we seek to create and practice. Power for provides the guiding star of transformative power, shaping our proposals, initiatives, agendas, and demands.

Transformative power grows from respect for self and interconnectedness with others – in all our diversities. It is the power inside us (power within), collective power together with others (power with), our power to speak out and act (power to), and power to articulate the change we want (power for). Transformative power can be identified, practised, and cultivated intentionally and serves as a guiding star for organising, leadership development, and strategy processes.

Oppressive actors and groups create their own forms of power within, power to, power with, and power for to pursue their agendas or obstruct change. Articulating our vision and values as change makers – our power for – is therefore essential in building transformative power. The power of collective imagination is a cornerstone of movement-building.

Download handout: Transformative power.

Download Graphic: Transformative power.

Activity 4: Transformative power in action

The four arenas of power help us unpack the many shapes and forms of domination, coercion, and oppression – or power over – that we face in our lives and activism. The arenas of power are often experienced as negative, but they are always contested. Each arena is a space where we can resist, engage, build, and transform power for positive change. How we source, build, and mobilise our own power, individually and collectively, can be unpacked into different kinds of “transformational power”, as we will explore using the framework here.7

Materials: The option that the group explored in Activity 2: Arenas of power: timeline, case study, or own experience.

Handout: Transformative Power

Facilitator note: Ahead of time, familiarise yourself with the Transformative Power concepts (see handout)

Step 1: Introduce the framework

Individually: Give people some paper or cards. Ask them to think about and write down:

- What sources of power do you draw upon to deal with conflict and challenges in your personal and work life?

- What sources of power do you draw on in your activism?

- What are some of the ways you have used your power to make a change?

In pairs: Discuss the sources and uses of power you each feel and deploy, and the similarities and differences in your experiences. Together, choose one source of power, and create a living statue (with moving parts) or skit that represents it.

Plenary: Each pair presents their living statues or skits, and the group guesses what they mean. Once the group has guessed, invite the presenting group to explain what they were thinking. Record what emerges on a flip chart. Ask at the end if anything is missing from the list of sources of power, and, if needed, add to the list. (You should note to yourself those that fall under power within, with, to, and for).

Synthesise and introduce the concepts of transformative power — ideas developed by women’s rights activists and feminists to describe the different categories of power people use to transform and improve their lives and their societies. Share the Handout: Transformative Power.

With help from the group, cluster the ideas on your list according to power with, within, to, and for. You can ask for other examples.

Stress how these forms of power interact and reinforce one another (for example, we often discover our sense of power within and power to in the context of working with others, power with; power for grows out of a deepening sense of the other three as we get clear what it is we want to create and change in the world around us).

- How do these forms of power resonate with our understanding of power? How are they different than power over and the four arenas of power? Anything we might add?

- Reflecting on our experiences, how do we foster power within? Where do we develop power to? How do we build power with? And what gives us a sense of power for over time?

- How do each of these powers contribute to strong movements?

Step 2: Transformative power in action

Small groups: Small groups: Invite each group to look for examples of – or potential for – sources and uses of power that could be transformative from the activity above in Step 1. Ask:

- What kinds of transformative power can you identify? What was the main source of this power? How was this power used? Look for examples of power within, power with, power to, and power for.

- How did these sources of power work together or support each other? How can they be combined to strengthen the power of activists and movements?

- Are there any forms of transformative power not discussed that you would add?

Plenary: Invite each group to share three or four insights or ‘aha!’ moments. Discuss the questions above. Finish by asking and discussing:

- How has transformative power changed or shaped your understanding of power?

- How does transformative power relate to challenging and changing power in the four arenas?

- What potential do you see for building transformative power with others in your own work or context?

Download this activity.

_______________________

4 JASS South Africa Regional Director

5 The three dimensions of power (visible, hidden, invisible) is adapted from Lisa VeneKlasen with Valerie Miller (2002), A New Weave of Power, People & Politics: The Action Guide for Advocacy and Citizen Participation, Practical Action Publishing, pp 47-50; drawing on Lukes, S. (1974, 2nd edition 2005) Power: A Radical View, Basingstoke/New-York: Palgrave Macmillan; and Gaventa, J. (1980) Power and Powerlessness: Quiescence and Rebellion in an Appalachian Valley, Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. See also Gaventa, J. (2006) ‘Finding the Spaces for Change: A Power Analysis’, IDS Bulletin Volume 37 Number 6 November 2006 and Bradley, A. (2020) ‘Did we forget about power? Reintroducing concepts of power for justice, equality and peace’, in R McGee and J. Pettit (eds), (2020), Power, Empowerment and Social Change, Abingdon: Routledge. “Contested arenas of power” and “systemic power” are new to this version of the framework.

6 Adapted from Lisa VeneKlasen with Valerie Miller (2002), A New Weave of Power, People & Politics: The Action Guide for Advocacy and Citizen Participation, Practical Action Publishing; Miller, V, L. VeneKlasen, M. Reilly and C. Clark (2006), Making Change Happen 3: Power. Concepts for Revisioning Power for Justice, Equity and Peace, Washington DC: Just Associates; and Bradley, A. (2020) ‘Did we forget about power? reintroducing concepts of power for justice, equality and peace’, in R McGee and J. Pettit (eds), (2020), Power, empowerment and social change, Abingdon: Routledge. See also J Rowlands (1997), Questioning Empowerment: Working with Women in Honduras, Oxford: Oxfam.

7 Adapted from Just Associates, We Rise Toolkit, Sources of Transforming Power, developed by Just Associates and activists in Southern Africa and Mesoamerica.