PEKKA: A grassroots women’s movement in Indonesia

CASE STUDY

PEKKA

A grassroots women’s movement in Indonesia

PEKKA transforms the lives of women heads of households through feminist popular education and collective organizing. The group began with village-to-village organizing among the poorest women around their immediate survival needs. This gave rise to a large network of independent savings-and-credit cooperatives, but the goal was always more ambitious. PEKKA has gone on to change many of the laws, practices, and norms that make these women outcasts.

Download this case study A4 or Letter size.

In the past, widows, divorced women, and single female heads-of-household were called janda, a pejorative term that implied a useless person, an outcast. Laws, policies, religious institutions, and society in general d meaned janda as worthless burdens and threats to the stability of marriage, families and community.

PEKKA savings cooperatives did not receive any outside funding, as was the case with other micro-finance programs. Instead, they were seeded by pooling women’s own resources – however meager – to ensure thatwomen could define and run their own groups and, over time, invest in collective solutions. Not surprisingly, women were reluctant at first. The project seemed outside the norm and difficult. Slowly, however, a handful of groups began exploring the cooperative idea. Some saved the money they previously spent on candy for their children, while others sold coconuts or cooked food to sell at the market.

Stigma runs deep

Even just talking with single and widowed women – let alone organizing them – created a lot of tension in communities. Called pimps and traffickers by some, PEKKA organizers found the first few years discouraging. The effort almost collapsed due to prejudices and resistance. Women had internalized the janda stigma and found it difficult to believe they could change things. They were nervous about rocking the boat even further by standing up for themselves.

However, from their shared pool of savings, groups gradually began making loans to each other on their own terms. As other women witnessed the benefits, new PEKKA groups formed. Each group chose an inspiring name and, with training from PEKKA in democratic organizing, practiced new forms of leadership and organ zation and built trust in themselves and one another. Dozens of cooperatives began to thrive in many different communities.

PEKKA’s teams also grew. Trained organizers led popular education, information, and coaching activities to strengthen the cooperative groups and leaders. PEKKA processes included games, songs, and dancing, creating moments of joy and fun and bolstering women’s spirits and bonds. Women broke taboos to learn about their bodies and self-care as an essential part of their political strategy. They learned how power operates in their lives and consciousness, both positively and negatively. This equipped them to plan together and deal with community resistance and conflicts among themselves.

Multiplying

As their resources grew, loans enabled many members to form viable incomegenerating enterprises. From earnings or loans from their cooperatives, women could provide education for their children and support for their extended families. Some groups built community centers that provided meeting spaces for the whole community and housed healthcare services, Wi-Fi, and training and literacy programs. PEKKA groups became recognized within their communities as important leaders and, when local elections rolled around, candidates actively sought their endorsements. Increasingly, PEKKA women have come to participate in local government and programs to promote fair resource allocations and budgets for community development. Some PEKKA leaders ran for local government.

To scale up their model, they created cooperative stores and marketplaces that provide fair-priced basic goods to the community and commodity exchange for rice and vegetables. By contrast with consumerism and platics, these markets bolster sustainable, local food production and a return to traditional housewares, such as baskets and cloth. They eliminate dependency on moneylenders, middlemen, and plastic products from outside. Annual PEKKA fairs showcase members’ contributions and achievements. Local and regional officials inaugurate the festivities, and local media cover them. In these ways, PEKKA’s national visibility and credibility increased in the eyes of the government and civil society.

As the cooperatives evolved, women faced legal and religious barriers to their roles as heads of households. Without legal recognition, they could not claim state benefits or appeal for divorce.

PEKKA launched a grassroots campaign to lobby national government for legal status for janda and for expanded access to mobile courts, especially in remote areas. In the process, PEKKA trained teams of local paralegals to navigate legal systems on behalf of other villagers, both women and men.

PEKKA expanded popular and political education to improve women’s skills and to educate donors and international agencies about organizing, movement-building, gender justice, and social change. When outside researchers and groups want to study the situation of women in the region, PEKKA leaders insist on participatory research to ensure that the information also benefits their campaigns, combining the knowledge of formal researchers with that of the community. Information-gathering now centers on lived experience and power dynamics in local communities.

Backlash and response

As PEKKA grew, conflicts emerged over women’s growing public roles and the challenges they posed to well-established inequalities. Moneylenders, religious leaders, and some local officials felt their power being questioned. Using slander and threats, opponents sought to intimidate and silence PEKKA members and isolate them, particularly as religious conservatives – often funded from the outside – have gained political power and influence and sought to reverse gains in women’s rights.

However, community leaders recognize the economic and social benefits gained from PEKKA groups and so name-calling has lost some of its potency. PEKKA cultivates good relations with regional and national media. Some PEKKA members trained to be broadcasters, established community radio stations and can counter misinformation and slurs. PEKKA also collaborates with Islamic scholars and clerics who are concerned about discrimination against women, to offer research and community training programs for local imams.

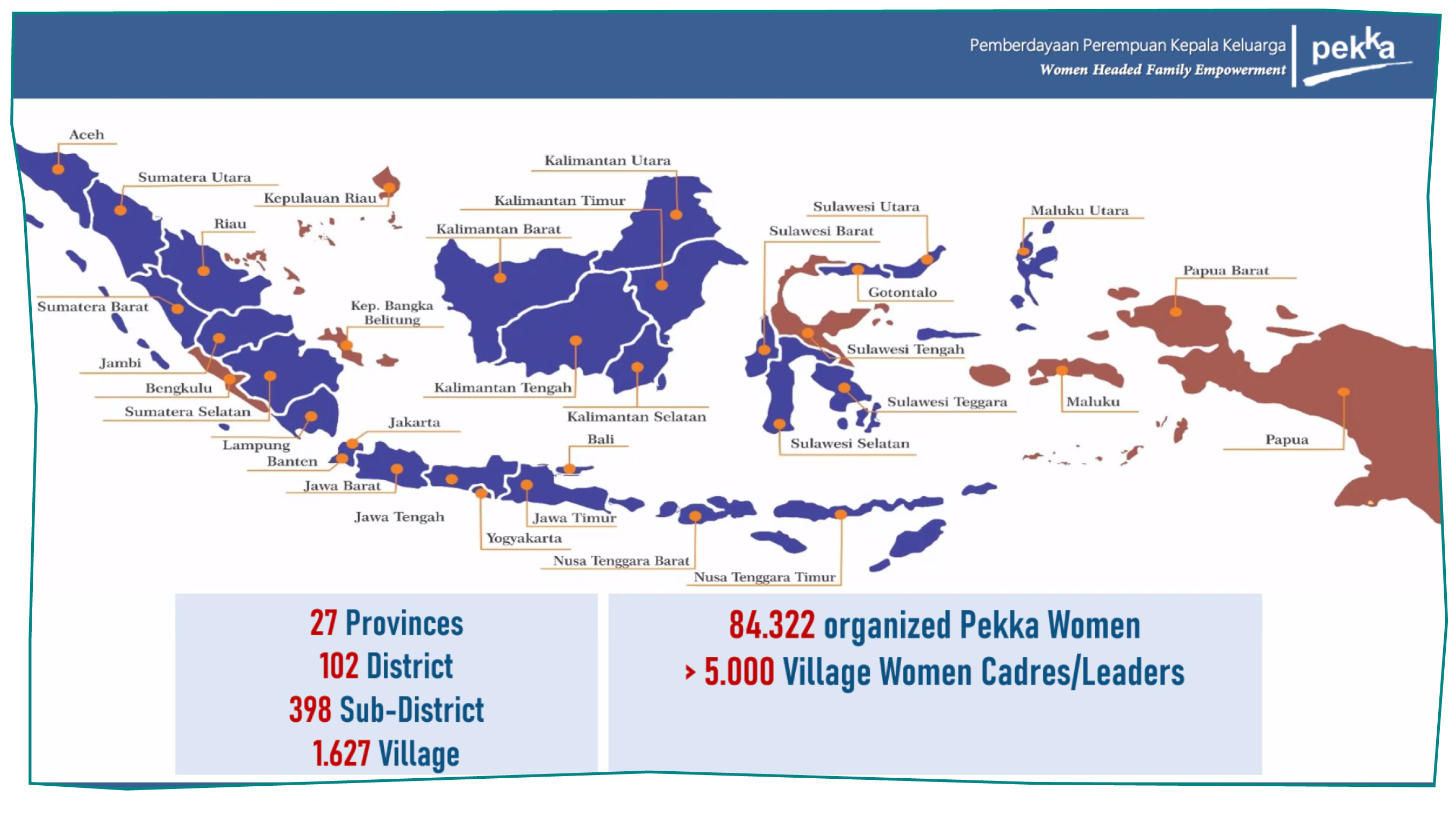

In 2017, PEKA became an autonomous national federation, led by grassroots women and supported by a network of PEKKA organizers and popular educators. By 2023, PEKKA had organized over 84,322 divorced, single, and widowed women – among the most marginalized in Indonesia – in 1,627 villages throughout 27 of the country’s 37 provinces. More than 5,000 PEKKA members are now village leaders. Today, PEKKA women continue to dream big – strengthening their individual and collective livelihoods, influence, and vision.