The MLT should have a sound understanding of UN integrated planning and its interaction with mandate design processes, as well as relations between UNHQ and the field. At the same time, there will be different approaches to planning within any integrated mission, particularly between the military/police and civilian components. The MLT should encourage flexibility and agility in planning processes through close interaction and information sharing.

In addition, each UN field presence should have standing coordination arrangements that bring together the UN system in an effort to provide strategic direction to and planning oversight of the joint efforts of the Organization to build and consolidate peace in the host country. The configuration and composition of integrated or joint planning structures will vary from one mission to another, based on the scale and nature of the UN operation and the level of strategic and programmatic coordination required, and in line with the principle that “form follows function”. Unless planning is driven by the MLT, the unity of purpose of the mission becomes incoherent and its mission support component (its budgetary and logistical resources) struggles to provide timely support. The buy-in and active engagement of the MLT is therefore essential for a successful and coherent planning process in support of mission implementation. At the very least, the MLT must give overarching planning direction to enable a mission planning process to be cascaded down through all components. This forms the basis of a mission plan.

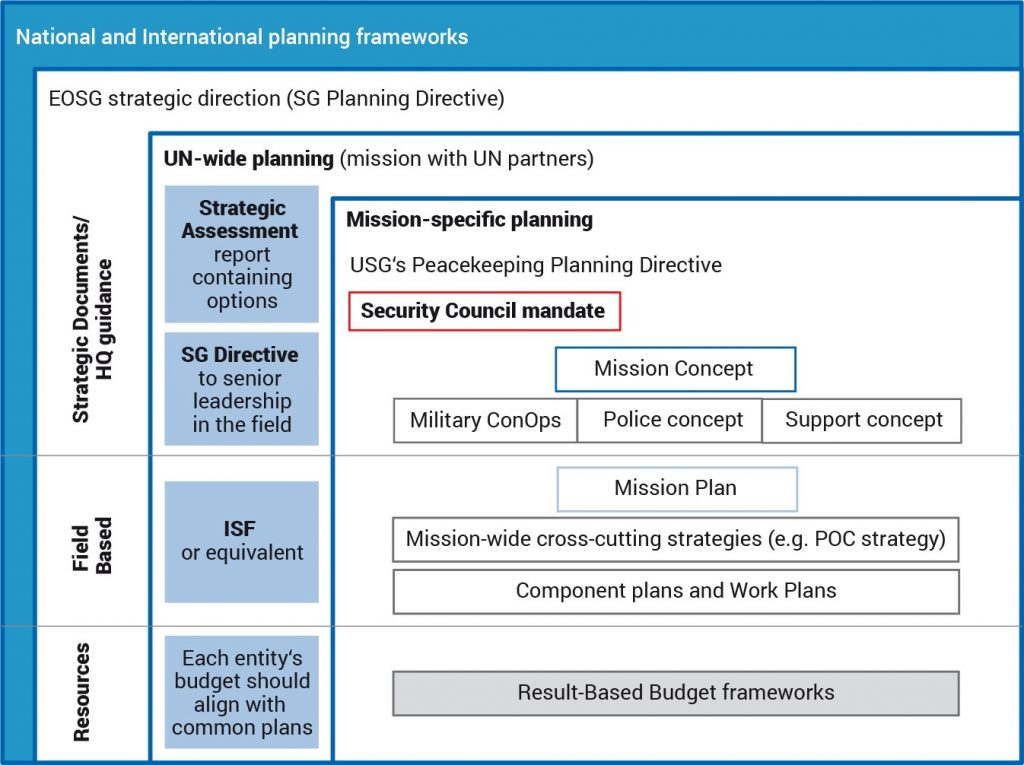

Regardless of its configuration, the coordination architecture should fulfil key functions at the strategic and operational levels. Strategic planners in all UN entities should have a shared understanding of their purpose and core tasks, the composition of their teams and the organization of their work. At the mission level, Joint or Integrated Planning Units help bring together expertise across all disciplines to ensure a mission-wide planning structure and plan (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 United Nations planning frameworks

Utilizing assessment and planning tools effectively and creatively

Integrated assessment planning (IAP) is defined as any UN analytical process at the strategic, programmatic or operational level that has implications for multiple UN entities, and which therefore requires their participation. There are nine guiding principles of IAP:

- Inclusivity. Planning must be undertaken with the full participation of the mission and the UNCT, and in consultation and coordination with UNHQ.

- Form follows function. The structural configuration of the UN integrated presence should reflect specific requirements, circumstances and mandates and can therefore take different forms.

- Comparative advantage. Tasks should be allocated to the UN entity best equipped to carry them out and resources distributed accordingly.

- Flexibility based on context. The design and implementation of assessment and planning exercises should be adapted to each situation and built on a continuing analysis of the drivers of peace and conflict and related mission options.

- National ownership. This is an essential precondition for the sustainability of peace.

- A clear UN role in relation to other actors.

- Recognition of the diversity of UN mandates and principles.

- Upfront analysis of risks and benefits.

- Mainstreaming. All IAP processes should take account of UN policies on human rights, gender, and child protection, among others.

In order to facilitate overall UN coherence, each mission should develop an Integrated Strategic Framework (ISF) that reflects a shared vision of the UN’s strategic objectives and a set of agreed results, timelines and responsibilities for achieving synergies in the delivery of tasks critical to consolidating peace. Other UN planning frameworks, such as the UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework, can serve as the ISF. The purpose of an ISF is to:

- bring together the UN system around a common set of agreed peacebuilding priorities;

- identify common priorities, and prioritize and sequence agreed activities;

- facilitate a shift in priorities and/or resources, as required; and

- allow for regular stocktaking by senior managers.

The scope of the ISF should be limited to key peace consolidation priorities that are unique to the context of each mission area. Because they involve highly political and sequenced activities by a number of UN actors, many typical mandated tasks – such as disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR); security sector reform (SSR); the rule of law; the return and reintegration of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees; the restoration of state authority; and addressing human rights violations – are particularly challenging and time-consuming. An ISF provides an opportunity to create clarity in the overall approach and establish priorities and a framework for mutual accountability.

Mission planners should be aware of other assessment and planning processes, and actively seek to create substantive linkages with the ISF wherever possible (see Figure 2.2).[1] Such processes may include a Humanitarian Response Plan.

THE Comprehensive Performance Assessment System

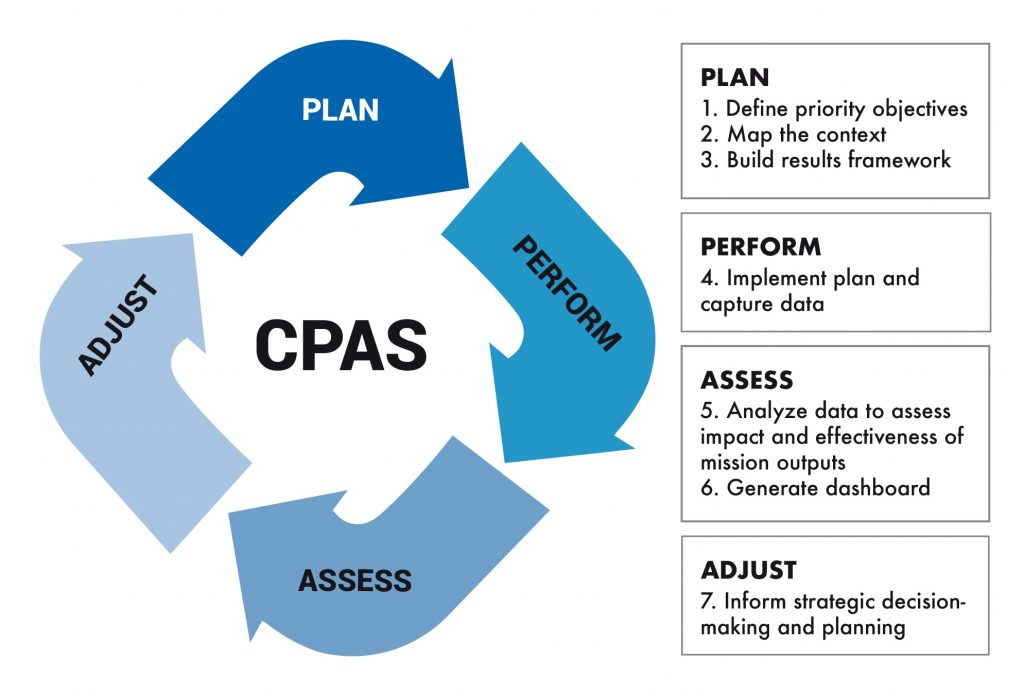

The Comprehensive Performance Assessment System (CPAS) for Peacekeeping Operations was launched in 2018 in order to give peacekeeping missions a tool with which to measure their impact. The system forms part of the Integrated Performance Assessment Framework called for in UN Security Council Resolution 2436 (2018) on peacekeeping performance.

CPAS is a context and mission-specific planning, monitoring and evaluation tool. It helps translate mission objectives into components and work plans. It enables the MLT to make decisions aiming to improve performance by maintaining or scaling up those activities that have a meaningful impact and adapting or ending those that do not. The system assesses mission performance by analysing its effect on the knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of the people and institutions the mission needs to influence in order to prevent violent conflict and sustain peace. It does so by analysing the relevance, extent and duration of the mission’s actions on selected outcomes, identified during the planning process.

CPAS provides the leadership team with evidence of the impact the mission is having, and an analysis of where adjustments are necessary to improve performance. This enables the leadership team to optimize the allocation of resources and direct the mission’s focus in ways that can maximize performance and continuously improve mandate implementation. The system is an iterative adaptive cycle that starts with a planning process and that ends with adjustments made to future plans and operations, based on an assessment of performance (see Figure 2.3). In large multidimensional missions the system will generate quarterly performance assessments in order to enable these missions to adapt with more agility to their fast-changing circumstances. Over time the data and analysis generated by CPAS will help inform the reports of the Secretary-General to the Security Council, and the Results-Based Budgeting reports of the missions to the Fifth Committee of the General Assembly.

Figure 2.3 The Comprehensive Performance Assessment System

Context analysis: The drivers of peace and conflict

In recent years, there has been an increased push for data-driven peacekeeping. Conflict systems analysis constitutes a key management tool and a central point of departure for integrated planning and operations. Such analysis helps to identify the drivers of peace and conflict, and the likely areas in which intervention will be required to achieve the mission’s strategic objectives and contribute to peace and security.

In generating the analysis, the mission may make use of existing peace and conflict analyses such as the internal UN Common Country Analysis, external research or create a lighter version. For example, a workshop with a small group of national and international experts at the start of a mission or planning cycle may help identify drivers of peace and conflict. At the other end of the scale, the analysis can also be developed as a full peace and conflict monitoring system. Regardless of its scope and depth, the analysis and its identified options for action need to be an integral part of strategic and operational management throughout the planning, implementation and follow-up processes. It is a continuous process based on intelligence information, identification of and dialogue with key stakeholders, and a constant assessment of contextual changes.

Done well, context analysis can become a key part of crafting and adapting the political strategy and mission concept. It also provides a method for identifying the possible negative impacts of the mission, and ensures that the mission applies a “Do No Harm” approach.

While there are various methodologies for undertaking a peace and conflict analysis, it should as a minimum include the following four elements:[2]

- A situation, context or profile analysis. That is, a brief snapshot of the peace and conflict context that describes the historical, political, economic, security, sociocultural and environmental context. As a key starting point, this analysis should focus on the nature of the political settlement and its legitimacy – whether it is disputed and if so, by whom and why.

- An analysis of the causal factors of peace and conflict. This should identify and distinguish between structural causes, intermediate or proximate causes and immediate causes or triggers. This causal analysis should attempt to establish patterns between the various causes of conflict and peace, perhaps by using a problem tree. The result should provide a clear idea of the key drivers of peace and conflict and allow the mission to plan to address the most important of these – that is, to reduce the effects of the drivers of conflict and strengthen the drivers of peace. In essence, this will also facilitate the prioritization and sequencing of different mission outcomes and outputs.

- A stakeholder or actor analysis. Focusing on those engaged in or affected by conflict, this element analyses their interests, positions, capacities and relationships. It is essential to integrate gender and youth lenses in this analysis (see 6.2 Women’s Role in Peace and Security Promoted, and 6.3 Youth Participation Supported). In particular, the stakeholder analysis must map patterns of influence among the various actors and identify the resources that will be required to enable each actor to achieve their agenda. It is essential to map the actors that use violence to achieve their goals, as well as those that use

collaborative actions to contribute to peace. The mapping exercise should also include formal and informal networks (noting that women may be more engaged in informal or community networks than official ones). This will generate an understanding of the key current and potential future actors, which will be central to formulating the mission’s political strategy towards them. - A peace and conflict dynamics analysis. This element should synthesize the resulting interactions between the peace and conflict profile, the causes and the actors, and provides potential scenarios, drivers of change and contingencies for the different scenarios. The latter will be essential for contingency planning and for ensuring the preparedness of the mission for future developments.

Prioritization and sequencing

In the early post-conflict period, national and international efforts should focus on achieving the most urgent and important peace- building objectives. The challenge will be to identify which activities best serve these objectives in each context. Priority setting should reflect the unique conditions and needs of the country, as identified in the peace and conflict analysis, rather than be driven by what international actors can or want to supply. Several operational activities will be needed to achieve an output but it is unlikely, given the limited resources available to a peace operation, that they can all be implemented at the same time. Prioritization will ensure the optimal use of available resources.

There are clear differences between prioritization and sequencing. Prioritization is a function of the importance of an activity. This does not necessarily mean that some activities must wait until a prioritized activity has been completed before they can begin. In contrast, sequencing means that one activity should not start until another has been completed. Combining the two approaches, an output can have a high priority, but could be sequenced to a later stage when the context is more conducive to change. For example, supporting a national reconciliation process may be a high priority but reconciliation initiatives can be sequenced to begin at a time when the political conditions are more favourable and national ownership is stronger.

During the planning stage, efforts should be made to both prioritize and sequence activities. The MLT should give direction on their priorities, and the planners can then provide the sequencing options. Legitimate international and national representatives of the host country should participate in these efforts. A plan of sequenced actions is based on a notional understanding of how events might unfold. Planned sequencing will almost always be disrupted by the unpredictability of activities on the ground. Prioritization and sequencing must remain flexible in order to adapt to the changing situation. Without systematic prioritization and sequencing, however, the mission will not know where it is heading or where to put its limited resources; and the influence of external factors will be even more significant and disruptive.

Integrating a gender perspective at every stage

Any situational analysis, as well as the ensuing planning and action, must consider all of the population and variations in living conditions, economic and political life and needs. Accordingly, a gender perspective must be an integral part of all analysis and planning. The MLT must be conscious that a UN peace operation is likely to be a critical mechanism for progressing the essential role of women in peace and security, without which the chances of a sustainable peace are small.[3]

Without an active gender perspective across the work of UN peace operations, missions will only see part of the overall picture related to the drivers of peace and conflict, the threat environment, the risks to civilians and the opportunities for sustainable peace. Gender expertise within the mission is essential to ensuring that peacekeeping activities are responsive to the different needs of women and men, and that resources are allocated effectively to support the WPS Agenda within the mission.

UNMIL: Long-term strategic objectives versus competing operational tasks

There was broad consensus that the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) could have done more to support the host country in a number of vital areas, especially national reconciliation and constitutional reform. Critical issues such as decentralization of public services and land tenure reform could have been prioritized and followed consistently from the outset to ensure peace was sustained on the basis of social cohesion.

Addressing the structural drivers of conflict – the absence of a just social contract and human security had neither featured strongly enough nor been pursued vigorously in Liberia’s post-conflict interventions. As UNMIL neared its closure, these issues remained largely unresolved. This reality exposed the odd absence of a comprehensive approach to planning for peacekeeping operations.

As a result of the government’s lukewarm attitude to the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation

Commission, national reconciliation in Liberia never went beyond a set of disparate and poorly funded initiatives that failed to produce significant results. Meaningful progress on this critical issue could have been achieved by bringing a sense of “reparation” to the most war-affected areas and communities through targeted development investments.

In addition, memorialization of the victims, accompanied by a formal acknowledgement of the wrong done to them and their families, as well as a collective expression of regret and apology, could have gone a long way to bring closure to the emotional agonies experienced by thousands of Liberian families. Furthermore, adoption of critical constitutional amendments and enactment of critical draft legislation on land tenure rights and local governance could have helped address some of the deep-seated historic factors responsible for marginalization and national disharmony.

Yet, the mission’s attention and limited resources had remained thinly spread for too long across an expansive array of mandated tasks. During the transition period, the mission requested and secured a four-fold increase in its programmatic funding, which provided the badly needed resources for implementing some of the most critical interventions through the UN Country Team, civil society and non-governmental organizations.

It is crucial for all cycles of a peacekeeping mission, but particularly in its final stage, to make use of

programmatic funding for projects in support of mandate implementation. In UNMIL’s case, programmatic

funding was a key enabler in residual areas of mandate focus and served as a critical tool in supporting our good offices and facilitation with the government, political parties, civil society, media, and the public.

Farid Zarif, SRSG UNMIL, 2015–18

Integrating a gender perspective is a mission-wide commitment that has to start with the MLT. A gender-responsive analysis that incorporates the needs of women and– as well as men – and considers power dynamics in society can identify indicators that serve as early- warning signs of violence or potential threats to the mission. This is particularly important for missions that have the protection of civilians as part of their mandate, as it can enhance the mission’s ability to assess threats and respond more effectively to them. Failure to undertake analysis through a gender lens can have a detrimental and long-term impact on the whole of society that could set back peace processes and future peacebuilding efforts.

Intelligence-based decision making

From the outset it must be clear to the MLT that intelligence in UN peace operations refers to the non-clandestine acquisition and processing of information by a mission within a directed mission intelligence cycle to meet the requirements of decision making and inform operations related to the safe and effective implementation of the Security Council mandate. Intelligence data can also inform the peace and conflict analysis to assist with strategic and operational decision making. In this context, it is the fundamental purpose of intelligence to enable missions to take decisions on appropriate actions in order to fulfil their mandates effectively and to enhance the security of all staff.

More specifically, peacekeeping intelligence is intended to support the provision of a common and coherent operational picture; provide early warning of imminent threats through good tactical intelligence; identify risks and opportunities; and contribute to force and staff protection. At the same time, peacekeeping intelligence can provide the MLT with an enhanced understanding of shifts in the strategic and operational landscape that present risks or opportunities for mandate implementation.

The precise intelligence structure will vary between missions, depending on the mandate and the resources made available by TCCs. It is important that the MLT takes appropriate measures to safeguard the analytical integrity of the mission. This entails allowing the intelligence cycle to run its course and being wary of the all-too-common phenomenon of members of staff seeking influence by maintaining a monopoly on information.

Utilizing emerging technology

New technologies – including monitoring and surveillance technologies – have been made available to missions to a varying degree. The MLT should regularly request expert opinions from advisers and subject- matter experts from all three components on areas where new technology might be used to facilitate the implementation of the mission’s mandate. The use of technology is primarily aimed at supporting decision making and enhancing security. Examples of recent technologies that have been usefully deployed include situational- awareness platforms or systems (such as SAGE and MCOPS), unmanned aerial vehicles, ground radar and closed-circuit television.

In addition to technical issues that must be carefully coordinated with the host country, such as radio frequency allocation and airspace management, monitoring and surveillance technologies requires careful political management with regard to its potential intrusiveness and the sharing of information. The MLT must ensure that the mission’s use complies at all times with the principle of impartiality and is in full accordance with international and national laws. A mission must not engage in illegal activity in order to collect information.

- UN DPKO, Policy on Integrated Assessment and Planning (2013). ↵

- This section is based on an edited version of UN DPKO, Integrated Planning and Assessment Handbook (2014), p. 26; and the draft 2018 policy. ↵

- United Nations, ‘Action for Peacekeeping: Declaration of Shared Commitments on UN Peacekeeping Operations’, 16 August 2018. ↵